Conservative MP Dominic Raab talks to Mike Harris about civil liberties, free speech and how he “wouldn’t lose any sleep” if the UK’s communications data bill were canned

This is the first of a new Index Interviews series

LONDON, 16/10/2012 (INDEX). Dominic Raab’s father fled Czechoslovakia just before the Second World War. The Conservative politician cites the fall of the Berlin Wall as one of his biggest political influences and Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn as the writer whose life he most admires. In many ways, his style is from another generation of politicians; he shoots from the hip describing Vladimir Putin as “a very Machiavellian, ruthless politician”, he is unaccompanied by an aide, and, rarer still, he doesn’t check his BlackBerry every five minutes.

Index is meeting Raab in a side room off Portcullis House, Parliament’s new office block for members of Parliament (MPs) and their staff. On the agenda are free speech issues both in the UK and abroad — from the Leveson Inquiry to the Kremlin’s suppression of Russian NGOs.

Offence and self-censorship

Let’s start with an easy question: Does he believe the culture of offence has got worse? He does.

“There is certainly much more legal restriction on what you can say. We’ve seen it with the incitement to religious hatred debate,” he says, “the glorification of terrorism debate and the ASBOs (Antisocial Behaviour Orders) that originated under the last government.” His concern is that these limitations are making society less open: “We’re narrowing the space where free speech and open debate takes place.

Raab defends preacher Philip Howard, who was banned from street preaching by Westminster Council in 2006:

I used to walk past him on Oxford Street with his microphone. The eccentricities of British life thrive on there being an open space where free expression can take place, and I don’t think most people thought he was such a nuisance that he ought to have been banned from preaching. We’re seeing the salami slicing of free speech.

The law I draw is the very clear one that John Stuart Mill drew, that you shouldn’t be saying things which incite violence or disorder, or cause tangible concrete harm to other people. Mere offence or insults don’t satisfy that test.

Raab is clear he thinks the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has over-prosecuted free speech cases in the past citing the Paul Chambers Twitter joke trial case: “Aside from the free speech issue, what a waste of money!”

Paul Chambers, who was found guilty of sending a menacing tweet, last July won his high court challenge against his conviction. He had tweeted in frustration when he discovered that Robin Hood airport in South Yorkshire was closed because of snow. Eager to see his girlfriend, he sent out a tweet on the publicly accessible site declaring: “Crap! Robin Hood airport is closed. You’ve got a week and a bit to get your shit together otherwise I’m blowing the airport sky high!!”

On Chambers he adds the firm he worked for was “gutless” for firing him during the CPS prosecution.

Thinking about the Innocence of Muslims controversy, I ask Raab if he thinks there’s a propensity to self-censor on controversial topics. He agrees:

I think politicians are very cautious that anything they say can be skewed or taken out of context. With excessive political correctness we’ve become ever more cautious as a class. On the other hand, there are areas where you have to be responsible in addressing them.

Of course it’s easy to see why MPs may wish to keep their heads down. The news cycle is quicker than ever. An off-the-cuff comment by a politician will trend on Twitter and be picked up by rolling 24 hour news channels desperate to fill their schedules within minutes. Is this super-fast news cycle making politicians self-censor?

“Well, it’s obviously not having an impact on the (Mitt) Romney campaign…” During the campaign, US Republican candidate Romney said his job was “not to worry about those people”, referring to the 47 per cent of people who don’t pay income taxes.

He switches to serious: “The point at which we down tools and stop speaking up for what we believe in there’s no point in being a politician.”

He relates back to his election in 2010, in the aftermath of the MPs’ expenses scandal:

If you look back at the 2010 election, and I think this is true of all politicians, the thing many of us realise most of all is how low the political class were and the fog of mistrust that hung in the air in the aftermath of the expenses scandal. There’s a deeper malaise, a feeling that politicians are colluding in the system and they don’t really stand up for what they believe in they just say what they’re supposed to. That is very dangerous. It is not just a question of political correctness … but a question of public trust in their elected representatives to stand up and have a conviction even if it is uncomfortable.

The expenses scandal was triggered by the leak and subsequent publication by the Telegraph Media Group in 2009 of expense claims made by MPs over several years. Public outrage was caused by disclosure of widespread actual and alleged misuse of the permitted allowances claimed, following failed attempts by parliament to prevent disclosure under Freedom of Information legislation.

It’s an interesting proposition: self-censorship is undermining trust in MPs. It’s certainly a cultural commonplace from The Thick of It to Yes Minister that MPs are unthinking automatons who blindly follow the orders of their special advisors, civil servants or media handlers. Raab thinks this self-censorship is ultimately self-defeating: “Whilst there is huge pressure on MPs in a way there wasn’t before because of social media and the 24 hour news cycle, there is also a huge repository of good will for those who are not deterred by the chilling effect of the professional pessimists in the media. The bottom line is that MPs and elected representatives ought to have a little more backbone and not give in to the online lynch mob.”

On Leveson

The Leveson Inquiry hangs over the British media. Raab points out that the IPSOS Mori Trust in Professionals Poll for years put trust in journalists below politicians: “The public know they’re not getting an honest account from the media”.

That was until the MPs’ expenses scandal.

Now, he views Leveson as an opportunity to help clean up the media. “There are two acid tests for Leveson. Will any proposals deal with the trigger for Leveson, which were the phone-hacking (that was already a criminal offence), and the reports of newspapers bribing police officers? These are the two things that concern me and I think the public care about the most.”

But, he adds: “Whether we need new legislation for this is a different question.”

On statutory regulation versus self-regulation, Raab is clear: “I am a free speech guy. I will be very reticent to move to a system that ends up having a chilling effect on free speech or media debate. There’s a real risk that we get proposals that do the latter, but don’t address the former. But let’s see.”

Communications Data Bill: Fight against criminals or a snooper’s charter?

One of the themes of Raab’s book The Assault on Liberty is decent people entering politics with the right intentions and being got at by the machine of government. In the book, Raab names former National Council for Civil Liberties General Secretary Patricia Hewitt and legal advisor Harriet Harman as two advocates of civil liberties that went on to embrace illiberal laws.

One of the themes of Raab’s book The Assault on Liberty is decent people entering politics with the right intentions and being got at by the machine of government. In the book, Raab names former National Council for Civil Liberties General Secretary Patricia Hewitt and legal advisor Harriet Harman as two advocates of civil liberties that went on to embrace illiberal laws.

The parallel with the current Conservative-Liberal Democrat government is obvious with the coalition’s earlier commitment to “end the storage of internet and email records without good reason”, followed promptly by the government’s publication of the Communications Data Bill that will do exactly the opposite.

Raab adds: “I think there’s a few things at play. First, your view when faced by briefings on national security will change even if it’s only a shift … The second thing is something we’ve got to get much better at: pushing back at some of the lazy assumptions we’re fed by the security establishment. I mean, you think of the arguments made in favour of 90 days and 42 days detention! I haven’t heard anyone since suggest there is a serious national security issue or counter-terrorism issue.”

On 12 October 2008, the Government finally dropped the controversial plans to allow terror suspects to be held for 42 days without charge after they were rejected by the House of Lords.

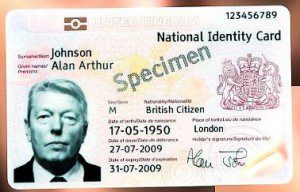

“You think of the scaremongering over ID cards and the assertions made by people in the police and plenty in the security establishment … on the risks of not going down that line of regulation, and does anyone seriously think at the end of that debate that ID cards would have made us safer?”

“Ministers have got to be a lot more demanding of the official advice they get and much more probing of it,” he adds.

In some rare Tory praise for their Liberal Democrat partners he adds:

I think coalition probably helps that, but I would say that the new surveillance proposals are exactly the sort that need to be looked at, scrutinised and tested both on the privacy side, the technological viability side, but also some of the wild assertions about the law enforcement value that have been made. I’m certainly not convinced that these proposals are worth the sacrifice of privacy in terms of the law enforcement bang for your buck you’re going to get.

In opposition, the Conservatives said the controversial Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA) went too far, but the Data Communications Bill will go even further. Raab retorts:

In fairness, there have been new checks placed on town hall snooping. Nonetheless, I think if we allowed the latest set of proposals to come through with plans for mass surveillance of every phone call, internet based message, email that we make, Skype and all the rest along with very sobering proposals for data mining and deep packet inspection … I think that would mark a ‘step change’ in the relationship between the citizen and the state. I would be very nervous about crossing that Rubicon unless I am absolutely convinced that it is imperative on the highest security and public safety grounds, and I don’t think that case has yet been made.

He draws a distinction between the Bill and RIPA, acknowledging that it does go further:

The safeguard in (RIPA) is the human manpower needed to sift through all of our personal data is ludicrously high and therefore, whilst there is a principled objection, the reality is, even with 10,000 requests a week for personal data, the impact on privacy is fairly confined. But if you add on the proposals in part two of the Data Communications Act for filtering arrangements and data mining and attempt to draw inference and patterns and trends from lots of our personal information and make judgements or assumptions or pre-judgements, about every innocent citizen as well as the guilty ones, I think that is a real sobering development well beyond qualitatively anything we’ve seen until this point.

I also think there are ways in which the Bill can be salvaged. [But] I wouldn’t lose any sleep if it was canned. We could do much more with the estimated £2 billion worth of money.

He hedges his bet: “If we are going to stick with it, it needs to be focused on terrorism and serious crime, limit very strictly who can have access to the data and I think we need a judicial warrantry system rather than these implicit plans for data mining and other surreptitious techniques which effectively reverse the normal presumption of innocence that we have in Britain.”

There has been a democratic urge towards measures that promote personal safety above individual liberty. In The Assault On Liberty, Raab points to the proliferation of closed-circuit television (CCTV), but it was often democratically elected councillors who introduced security cameras in response to public fears. As Index has pointed out, as the cost of surveillance equipment is dropping more governments are considering implementing it.

Raab questions the cost estimates provided by governments for such projects: “I remember with ID cards the original estimate of how much they would cost ballooned when it was looked at independently. I think the best thing that can be said about this is that the public have become increasingly sceptical the more they have seen fairly draconian proposals that haven’t on due scrutiny, whether parliamentary scrutiny or public scrutiny or seeing the operational practice, haven’t actually delivered on their law enforcement goals.”

Raab questions the cost estimates provided by governments for such projects: “I remember with ID cards the original estimate of how much they would cost ballooned when it was looked at independently. I think the best thing that can be said about this is that the public have become increasingly sceptical the more they have seen fairly draconian proposals that haven’t on due scrutiny, whether parliamentary scrutiny or public scrutiny or seeing the operational practice, haven’t actually delivered on their law enforcement goals.”

He’s also optimistic that the public is increasingly sceptical over politicians’ claims over national security:

“There has certainly been a huge amount of populist pandering and scaremongering in the wake of 7/7 and 9/11. I think the public have wised up to this and I also think they listen to the point of principle and the arguments against in perhaps a way they didn’t in the early 2000s.”

It’s this public scepticism and the longer parliamentary scrutiny the Bill will receive that he believes will neuter the most illiberal measures in the draft Communications Data Bill, says Raab.

“There’s a long time frame because of the pre-legislative scrutiny,” he adds, “and then we’ll have the Bill scrutiny … and I think that it will be a similar debate to the one we saw over ID cards which is there will be analysis over the point of principle and on privacy, and then there will be all the technical geeks will come out and scrutinise very carefully the viability. Then there will be quite a few independently minded law enforcement people like former ACPO president Sir Chris Fox saying this will not deal with top-end criminals and terrorists because they are smart enough to avoid this very obvious route of surveillance whether it’s with pay as you go phones, proxy servers, and all the rest.”

Open debate is key to scaling back the Bill. “Time allows for scrutiny which tends to puncture the myths and once the public turn against proposals like this there is no getting them back though actually I think in the long run we end up in the right place.”

Russia

In a previous interview, Raab highlighted Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn as the writer he most admires: “When he died last August, I bought a copy of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, his stark account of the denigration of the Russian people, especially peasants, in labour camps. For me, he stands out despite the fact that — or perhaps because — he wasn’t a liberal campaigner siding with the West in the cold war. He was just a straight talker who loved his country, with the moral clarity and courage to puncture communism’s lingering pretence to legitimacy.”

It therefore came as no surprise that Raab is animated when it comes to contemporary Russian politics, describing newly elected Vladimir Putin as “a Machiavellian, ruthless politician, who will do what it takes to cling on to power and he’s also got a smart sense of propaganda.”

Raab believes in highlighting cases such as that of whistleblowing lawyer Sergei Magnitsky. “It’s an astonishing Kafkaesque situation where a guy that exposes the biggest tax fraud in Russian history then gets persecuted for the same crime. It’s very revealing about the nature of Putin’s regime. We need to keep highlighting this.”

He is proud that the House of Commons unanimously backed his resolution calling for a UK version of the US Sergei Magnitsky Bill imposing targeted economic sanctions of those accused of collaborating in the imprisonment and ultimately, the murder of, Magnitsky. It has been slow progress for Raab but he believes “the government has inched in the right direction. The Foreign Office annual Human Rights report says that it will now be standard practice for anyone against whom there is evidence of torture or other similar crimes to be subject to a Visa ban. That was a shift. And we’ve also seen the Home Office send the Magnitsky files that were presented to the US Congressional Committee to their Russian embassy almost as a watch list to look for the 60 suspects if they try to apply for Visas in the UK.”

He believes that if the Magnitsky Bill passes in the US it will encourage the UK to, and significantly, that Foreign Officers Ministers have indicated a Bill to him. He’s clearly passionate about this case and the precedent this action would set. The Magnitsky Bill “is a neat mechanism that we could apply as a foreign policy tool. It’s about us, it’s not just about interfering or extra-territorial jurisdiction, it’s about us saying do we allow people into this country with blood on their hands, to walk up and down the King’s Road to do their shopping, to buy up property with their blood money. It is not just about their crimes it is about the moral approach we take. At the end of the day, it’s on us as Britain and me as a British lawmaker to take some responsibility for that and I don’t want us to be a safe haven for crooks, cronies and people who have committed the most egregious of crimes as in the case of Sergei Magnitsky.”

But is the process is entirely fair? For as flawed as Russia’s legal system is, none of the accused have been tried in an impartial court of law. Raab insists the punishment fits: “We’re not talking about taking their liberty, we’re talking about not letting them travel to the UK and the privilege of being on British soil or buying up British property. My proposal is that there should be an evidential threshold applied before targeted sanctions, with an appeal mechanism.”

Since Vladimir Putin’s re-election as President of Russia, a number of draconian new laws have been rushed through the Duma including the re-criminalisation of libel, a law to restrict civil society access to foreign funding and new restrictions on freedom of association that have been condemned by the OSCE. So what can the international community do? “Ultimately you’ve got to ask yourself what Vladimir Putin fears. I don’t think he fears an adverse ruling from the Strasbourg Court and I don’t think he fears being ticked off in the Council of Europe. What I think he does care about is diplomatic embarrassment, targeted economic sanctions, which is why I support … the Sergei Magnitsky law. Actions that hit him in the pocket are likely to have far greater influence than trying to think that he’s a good soul and all it will take is some time to smooth out a few of those rough edges.”

There’s almost an element of Marxist determinism in Raab’s analysis. “Russian membership of the WTO is a good thing. With trade and a burgeoning middle class history says you’ll see they’ll demand more representation the more economic influence they have. The economic argument is an important one.” As a vocal critic of the implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights, I ask him whether he thinks the Council of Europe has over-extended itself? He’s positive: “One of the pros of the EU and the Council of Europe … has been to sign governments up from previously unsavoury or despotic parts of the world and try and get them to live by the rules of the club … which are broadly speaking Western democratic norms.”

He concludes that the role of external parties may be unhelpful: “The truth is the Russian people need to work this out for themselves. I don’t believe in megaphone diplomacy. We need to be subtle and patient.”

With that, Index’s time is up. As I leave, in the Atrium of Portcullis House a prominent MP comes over to Raab to ask him for lunch. His staunch defence of civil liberties has certainly made himself one of the more notable members of the 2010 parliamentary intake. As with all politicians who claim to defend freedom of expression, the litmus test is not their rhetoric but how they vote on illiberal legislation — that test, luckily, is yet to come in this parliament.