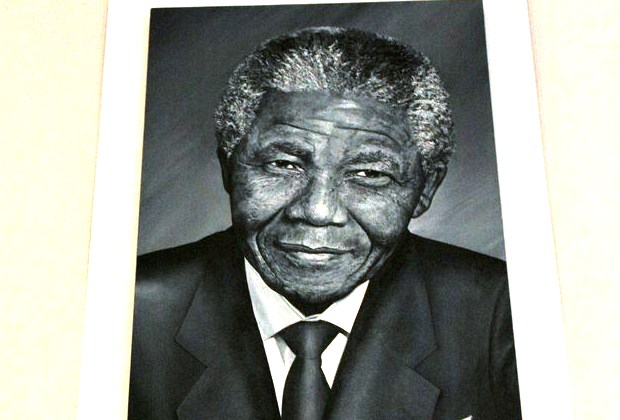

This is the moment to remember massive changes in South African life that are Nelson Mandela’s legacy says Rachael Jolley

This is the moment to remember massive changes in South African life that are Nelson Mandela’s legacy says Rachael Jolley

There it was, a Mandela legacy, up front and centre, hitting my eyes, as I squeezed into the back seat of a tiny car with five companions, on a whistle-stop sunset tour of the packed city streets of Durban in 1996. But it was what I didn’t see that was surprising – no sign any more telling my companions that they couldn’t go where I could go.

“That was the beach that we weren’t allowed to go on, there were signs right there that said ‘Whites Only’”, one of the guys told me as we headed away from the huge surf haven of the Kwazulu Natal seafront, where we had all been hanging out watching the surfers climb on top of massive curving waves.

These men, who were all part of Durban’s Indian community, had just adopted two foreigners, news reporters at conference, and insisted they showed us around their country. We crammed into the car as they argued about where to take us, immensely proud of the bustling seaside city they lived in, proud to show it off its spice markets and its Victorian architecture and its thriving bar scene to the kind of international visitors who for decades had stayed away while the barriers of the apartheid regime split the white and the non-white communities as effectively as the Wall had split Berlin.

It was almost impossible to believe that not long ago these overflowing streets, packed shoulder to shoulder with people of black, brown and white skins, had been forcibly divided into separate and deeply unequal societies.

At first glance, the enormous rolling sandy surf beach could have been on a seafront in Australia or in California, packed as it was with surf dudes, crashing waves, and with a cool café where everyone hung out at the end of the day. But our guides knew that the monumental physical changes that had happened in their country in the past few years were just one outcome of Nelson Mandela’s fight for their freedom.

What you felt fizzing in the air, in the conversation, and in hearts was the pure joy of that precise historical moment, where suddenly there was opportunity, and the barriers that said “Whites Only” had been torn down. No longer was public transport separated by colour of your skin; now the national parliament held representatives of all communities, not just one. Nelson Mandela had made these things happen, and that made him something more than just an average politician.

This was only a year or two after the first open election in South Africa, and South Africans felt that they were living through an historic time. Their pride in their country was infinite; everywhere I went, and year after year as I returned later, I would run into someone whose pride in that change overflowed: they always insisted on showing me a landmark of the struggle — a Soweto bar, where the owner wanted to talk about where her clientele came from and who they were, a house, a museum or a beach where one of those physical signs of their second-class status in their own country had been pulled down.

In his autobiography, Nelson Mandela talks about his personal motivation to become involved with the ANC and the fight to overthrow apartheid. It was fired, he wrote, by the unfairness of the life he and those all around him were forced to live: “I yearned for the basic and honourable freedoms of achieving my potential, of earning my keep, of marrying and having a family – the freedom not to be obstructed in a lawful life”. His leadership of the struggle finally resulted in a general election, open to all, in 1994.

The pictures miles-long, winding lines of people queuing for hour upon hour determined to vote in South Africa’s first free election, in 1994, are among the most iconic and enduring images of the second half of the 20th century. There were those, old and young, similarly fired by that sense of unfairness, willing to wait days and hours to go to the ballot box.

Twenty years after his inauguration the words of the first president of a free South Africa still have the power of something magnificent achieved. He describes being saluted by the South African generals and the highest commanders of the police, and being mindful of how a few short years earlier they would have arrested him, as their predecessors had imprisoned him. “The sun shall never set on so glorious a human achievement,” Mandela said as thousands of television cameras, and through them, hundreds of thousands of eyes, focused on him.

Mandela has ever since been a guiding presence at epic, and emotional moments, in his country’s history. South Africa’s victory at the Rugby World Cup in 1995 was so much more than a sports team winning a trophy: it came only a year after Mandela’s election, and rugby, more than any other sport, had been a symbol of division, a game for white men only and one in which South Africa had not been allowed to compete in the international arena since the late 1960s because of apartheid. Yet here was a cheering black president handing the trophy huge, white Francois Pienaar: the sight of the two of them, one so small, one so tall, swept up in a cloud of sound, symbolised the overwhelming joy of a new nation with a growing belief in itself and its future.

When Mandela handed over political power to others, commentators and the public questioned whether South Africa would change, or if the symbolic power he had instilled would slowly evaporate, the sense of moral good fade into corruption and despair.

Those concerns have again risen viscerally among those who yearn for South Africa to succeed. But, contrary to those who fear that Mandela’s passing may mask a moment when all that Mandela has achieved will start to slide away, Nic Dawes, editor-in-chief of South Africa’s Mail and Guardian newspaper, is optimistic. In an interview with Index on Censorship, he said he believes that the severe illness of the ex-president has brought his achievements back to the attention of those in authority.

“His legacy has not had the prominence that it ought to have done in public life. It has been too easily dismissed by many South Africans and political leaders. They have spoken of him as too easy on reconciliation or that he got it wrong on economic issues, and they have not put it front and centre in their own decision making.

“But it is being brought back to us in a way that it hasn’t been for a number of years, so there is optimism that we can recall again the value of his approach and contribution in a way that we haven’t always done recently.”

Nor does Dawes feel that this is a moment when the wheels will come off; he is confident that South Africa’s institutions, despite their flaws, are strong enough to help citizens to resist corruption and authoritarianism.

If Mandela’s legacy is summed up by one thing, it will be in symbolic moments, like the times when those “whites only” signs were torn down, no longer shouting that South Africa was a society where only its white people had opportunity, and aspiration, and when a reborn nation began its journey on a previously uncharted road to freedom.

This article was posted on 5 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org