Photo: Jimmy Trindade via Facebook

Brazil’s mass protests represent a new force in the country’s politics. The wave of demonstrations have shaken the country’s lethargic leaders into action, Rafael Spuldar reports

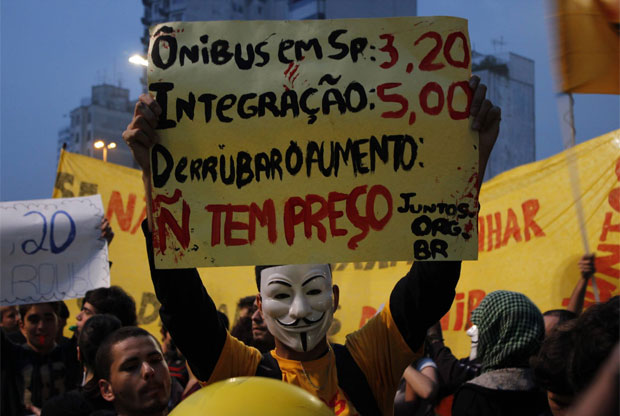

Initially organised by Movimento Passe Livre (MPL) to protest the rising cost of transport in Brazil’s largest cities, the demonstrations, which began in early June, have evolved and swelled in size to give voice to a range of grievances from underfunded health and education systems to political corruption and the huge cost of the World Cup.

Political scientist Pedro Fassoni Arruda from PUC-SP University said that these protests are undoubtedly a new form of participatory politics in Brazil – a country that hasn’t been used to mass demonstrations.

“There was uneasiness, a spreading feeling of discontent with the representative system. People have power once every four years at election time, but they are unheard during the period in between”, Arruda commented.

Though Arruda said he feels it is still early to say if this kind of mass protest will endure “things change quickly. A month ago no one could predict the size these demonstrations would eventually have. Not even the most optimistic members of MPL imagined a hundred thousand people out in the streets.”

Though not a certainty, Brazilians should expect future large-scale demonstrations. Scattered groups with different demands will mount protests via social media, according to professor Cláudio Couto from the Public Administration course at FGV University in São Paulo.

“If I were a cartoonist, I’d already have drawn an extraterrestrial landing in Brazil and asking the protesters to take him to their leader, like the sci-fi movies. That’s because we can’t see anyone that can be identified as a representative of this movement. Many protesters joined the demonstrations by themselves, not obeying any leadership, and this is a new pattern”, said Couto, who regards the 2014 World Cup and general elections as an opportunity for these groups to go back to the streets and voice their demands again.

Brazil’s politicians responded with uncommon speed to the crowds’ demands.

Officials in São Paulo – and, before them, the ones in the southern capital of Porto Alegre – reversed the rise in fares.

On the federal level, officials moved to meet protest demands to tackle corruption. For the first time since 1988 a Brazilian congressman, who was convicted of embezzling public monies and criminal conspiracy, was sentenced to prison. Further, all political parties united to quash a proposed constitutional amendment that would have limited the investigation powers of the public ministry. Prior to the demonstrations, the amendment had appeared certain to be adopted.

Federal deputies also approved a bill that applies 75% of oil extraction royalties on public education and 25% on the health care system — another demand of the protesters. In addition, the “gay cure bill”, which would have allowed psychologists to treat patients that wished to be “cured” of homosexuality, was withdrawn from consideration after pressure from the streets.

President Dilma Rousseff announced her intention last week to have a plebiscite to let Brazilians decide on changes to the political system. The referendum would include changes in political party financing and the apportionment of congressional representation, possibly a district-like framework similar to the US. The proposed plebiscite was delivered to Congress on 2 July.

Rousseff first’s idea — now abandoned — had been to use the plebiscite to decide on the creation of a special constitutional assembly aimed at political reform – a move criticized by jurists and members of the federal Supreme Court. Now some politicians want political reform to be discussed first in Congress and later brought to a public referendum, a solution the president rejects.

A plebiscite should raise concerns in Brazil, said FGV’s Couto.

“A plebiscite turns everything into a matter of ‘yes or no’, ruling out negotiation, the ‘art of compromise’, which is the defining element of politics”, he added. “It will not solve all problems, it is not a panacea. I believe a plebiscite creates a low-quality democracy.”

PUC-SP’s Arruda is more optimistic about the plebiscite. He believes the president seized a one-of-a-kind opportunity to bring a fundamental issue into the light.

“Not only the population has gone out to the streets, the political class itself has also stepped out of lethargy. It is a very opportune moment to announce the intent of reforming politics, which is an idea dear to so many parties.”

But even these moves could not prevent the plummeting popularity of most Brazilian politicians after demonstrations bgan. Rousseff’s approval rating fell from 57% to 30% in only three weeks, according to a national survey. São Paulo’s governor Geraldo Alckmin and mayor Fernando Haddad also had poor results.

“What we have now is clearly a representation crisis”, says Couto. “Nobody’s satisfied with the ‘powers that be’, no one is safe from public scrutiny. The repression of protesters against political parties seen during the demonstrations – which is a worrying thing by itself, for there is no democracy without political parties – is one more element on this crisis.”

Couto referenced reports that protesters ordered participants carrying flags belonging to political parties to be expelled from the demonstrations. He sees this and the violent police reaction as worrying aspects of the unrest.

“Marching in one demonstration I caught myself warning people that [ordering parties’ flags to be put down] was wrong, it was censorship, that not even the police did it”, says Arruda. “These people didn’t realize the gravity of their gesture. Maybe they ignored the fact that the last time political parties were prohibited in Brazil was during the military regime.”

Arruda believes that some of the protesters acted like this after being manipulated by fringe groups that infiltrated in the demonstrations. “People act thoughtlessly when they’re in a crowd. They may not be ill-intended, but they often become a mass serving to some particular groups.”

Police violence was noted during the first weeks of unrest, especially in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, where protesters and media professionals were targeted by rubber bullets, stun grenades, tear gas and mace. Over the weeks, while demonstrations grew and became more diverse, sacking and beatings by far-right groups became common place during protests, leading to more clashes between the crowds and the police.

The demonstrations have also led to a debate over the demilitarization of police in Brazil – where each state has both Military Police, which is in charge of street patrolling and riot control, and Civil Police that mostly focuses on investigation.

“The military police has not made any transition from dictatorship to democracy. It follows the norms from the military period”, says Couto. “It does not have the expertise to deal with social problems that demand a kind of acting that’s not purely repressive.”

PUC-SP’s Pedro Arruda regards military police as excessively authoritarian. “During the recent protests police restricted people’s freedom of assembly and freedom of speech. People were detained merely ‘for inquiry’, something that happened only under the military regime, or because they carried vinegar to protect themselves from tear gas. It’s clear that the demilitarization of the police is something to be discussed.”

Rafeal Spuldar is a freelance writer based in Brazil. He tweets @spuldar.