Julia Farrington travelled to Northern Ireland to participate in the 2014 Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival in Belfast. While there she saw four plays that deal with the Troubles as head of Sinn Féin, Gerry Adams, was questioned by police.

A new mural of Adams appeared on the Falls Road in West Belfast what seemed like only a matter of hours after he was taken into custody. Officially launched by Martin McGuiness to a crowd of thousands of Sinn Féin supporters on Saturday, and it was subsequently paint-bombed. The murals, far from being memorials to past struggles, are alive and kicking.

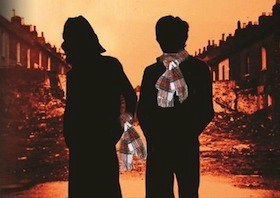

Across town in east Belfast, I went to Bobby “Beano” Niblock’s new play — Tartan at the Skainos Centre — passing the contentious murals of balaclava wearing Ulster Volunteer Force gunmen on the way. Niblock is a rare bird in Northern Ireland as loyalist voices continue to be massively under-represented in the theatre there. The play, though heavily laced with humour and raucously re-enacted 1970s hits, had a very dark message. It tells of betrayal within the loyalist community, as TC, the teenage leader of the Tartan street gang, is mentored, manipulated and ultimately murdered by older members of the community. The level of violence in Tartan completely chilled me; the young men graduating from what were seen as boys toys — crowbars, mallets and axes — to petrol bombs, guns and the crowning awe of a machine gun.

This play of street violence and male rite of passage, was the flip side of Flesh & Blood — three plays written, produced, directed and designed by women I had seen the previous day in a run through a week before they open at the Grand Opera House. I was invited by one of the playwrights, Jo Egan, whose play Sweeties revolves around the true story of a seemingly unperturbed victim of paedophilia and the devastation it causes her complicit friend. The other two plays were by comic genius Brenda Murphy and first time playwright and former leader of the Progressive Unionist Party, Dawn Purvis. All three tell stories centre on the experience of women and girls, firmly rooted in the domestic setting of home, street and neighbourhood; in the case of Sweeties, trapped by agoraphobia in a front room, or Dawn Purvis’ play through the eyes of a young girl, watching and commenting on life on her street, with the Troubles forming the backdrop. Brenda Murphy’s play was a deeply moving portrait of her mother’s struggle to bring up six illegitimate children who she had with a married man who lived around the corner.

Those three plays were so good to see. Women playwrights are strangely under-represented all over this country, when you compare to a much more equal landscape in fiction, biography and other written forms. But hearing those voices, the reality and humour of women in Belfast, a city which I found to be so acutely male dominated, was brilliant. I laughed and cried, and came away deeply affected by the lives I had seen on stage, the courage, compassion and humour of women left to deal with the fallout of male violence.

But in all cases the stage here is seeing untold stories, and in some cases unwelcome stories, coming to the surface; retelling, unearthing, revealing complex, individual stories that are hidden within the expression of communal identity of the murals.

This article was posted on May 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org