[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Members of Index’s youth board looked at three famous works that fell victim to the Russian censors”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the long-term consequences of 1917 Russian Revolution, which launched the global communist experiment, and the long-term impact that it had on free speech around the world. Here, three members of Index’s youth board give examples of works that failed to find favour with the authorities the revolution ushered in.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

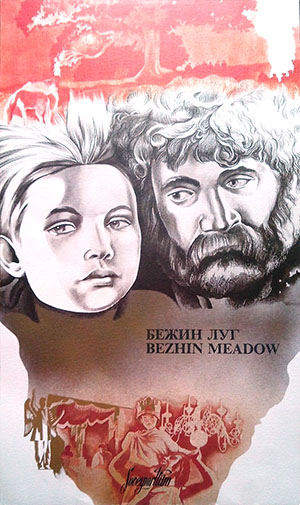

The original Italian edition of Dr Zhivago. Credit: Wikimedia

Dr Zhivago – Boris Pasternak

Isabela Vrba Neves (Stockholm)

A depiction of Russian life between the Bolshevik Revolution and World War II, Dr Zhivago (1957) by Boris Pasternak is a piece of literature presenting the reader with romance and the tragedies experienced by Russians during the early twentieth century.

Dr Zhivago tells the story of Yuri Zhivago, a man suffering hardship throughout his life, from becoming an orphan to being in love with two women and arousing the suspicions of those in power. Through an intricate plot introducing many characters, Zhivago witnesses the revolution and civil war, all while exploring questions of religion and philosophy.

Pasternak submitted his book for publishing in 1956 but was rejected in the Soviet Union due to it containing anti-Soviet passages and criticism of the Bolsheviks. As a result, the book was banned in the Soviet Union until 1988. However, in 1957 a manuscript was smuggled to Milan, where it was first published.

The following year Pasternak was awarded a Nobel Prize in Literature, which he had to turn down after being threatened with ejection from the Soviet Union. The award was later accepted in 1988 by his relatives.

A film adaptation of Dr Zhivago was released in 1965, starring the late actor Omar Sharif and Geraldine Chaplin. Immensely popular in Europe and North America, the film adaption was also banned for many years in the Soviet Union.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The cover of Stefan Zweig’s Beware of Pity. Credit: Wikimedia

The Collected Novellas of Stefan Zweig

Samuel Rowe (London)

As I was leaving a house on the outskirts of Copenhagen some summers ago, I was handed a bright orange hardback book. It was The Collected Novellas of Stefan Zweig. I was told that Zweig’s novel, Beware of Pity, had loosely inspired the 2014 Wes Anderson film The Grand Budapest Hotel and that Zweig’s works had been burned in the streets during the Third Reich. But this was not the first time his literature had been burned.

Not long before – 30 October 1929, to be precise – Krupskaia Lenin, wife of Vladmir, had sent out a circular to all librarians in the Soviet Union. It contained a list of literature considered decadent or which fostered “social pessimism”, and required they be removed from all public libraries. Zweig’s stories could have fallen into the former or the latter category; his stories were popular and hilarious, subversive and frank.

Once the procedure was completed, two copies of each title on the list were sent to the central library of each region, accessible only to qualified researchers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

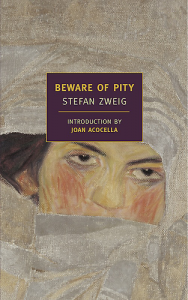

A poster for Bezhin Meadow. Credit: Wikimedia

Bezhin Meadow – Sergei Eisenstein

Sophia Smith-Galer (London)

One of the most famous films to have been scuppered by censorship in the Soviet Union was Bezhin Meadow, a film adaptation of the story Bezhin lug by Ivan Turgenev. The film, directed by Sergei Eisenstein, was believed to have been destroyed before its completion, but parts of it resurfaced in the 1960’s, allowing for a crude recreation.

The main character Ivan’s life story was based on the life of Pavlik Morozov, a young Russian boy who denounced his father to the Soviet Union and, ultimately, died at the hands of his family. It grew to become a story of political martyrdom after his death in 1932.

Sergei Eisenstein was nonetheless already a world famous film director – Battleship Potemkin (1925) is still used as an example of groundbreaking cinematography to this day – and is best remembered for pioneering the montage.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This piece was written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board. You can find out more about the youth advisory board here

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”100 Years On” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F06%2F100-years-on%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the consequences of the 1917 Russian Revolution still affect freedoms today, in Russia and around the world.

With: Andrei Arkhangelsky, BG Muhn, Nina Khrushcheva[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/magazine”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]