[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”95829″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]

The Guggenheim Museum in New York, after a week of resisting calls for the removal of three works from Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, announced that it will pull the works from the exhibition. These include two videos documenting performances with live animals in 1994 and 2003, and a sculpture that replicates a 1993 work including live insects, snakes and lizards. Their removal came in response to “repeated threats of violence” and “concern for the safety of its staff, visitors and participating artists.”

The Guggenheim’s alarming action continues a growing worldwide trend in which threats of violent protest are silencing artistic expression and posing a danger to free speech in general. Whether or not the provocations of artists are defensible or morally unacceptable, we need to take an uncompromising position against threats of violence. When cultural institutions cave in to such threats, others who are convinced of the moral rectitude of their cause are encouraged to embrace similar tactics. This time it is animal rights activists. Next time it could be religious or political extremists.

Cultural institutions need to work with law enforcement to protect their staff, the public, and the works on view and to ensure that the right to protest does not override the right to free expression. Every time threats of violence succeed in silencing expression, fear’s stranglehold on the imagination tightens, stifling our ability to fully explore the world and our place in it.

The protesters insist that this is not about free speech: they claim the controversial works are not art expressing a controversial view but are themselves unacceptable acts of cruelty. That may have been a valid argument had the Guggenheim commissioned the performances represented in the videos. The Museum did not do that. The show’s curators sought to represent a period of art production from a specific political and cultural context. Artists in that period used live animals in their performances on multiple occasions.

Whatever the ethical issues may be, the fact of those historical performances remains. Their erasure from the show cannot reverse history, and will only succeed in offering viewers a sanitized version of an intense and troublesome period.

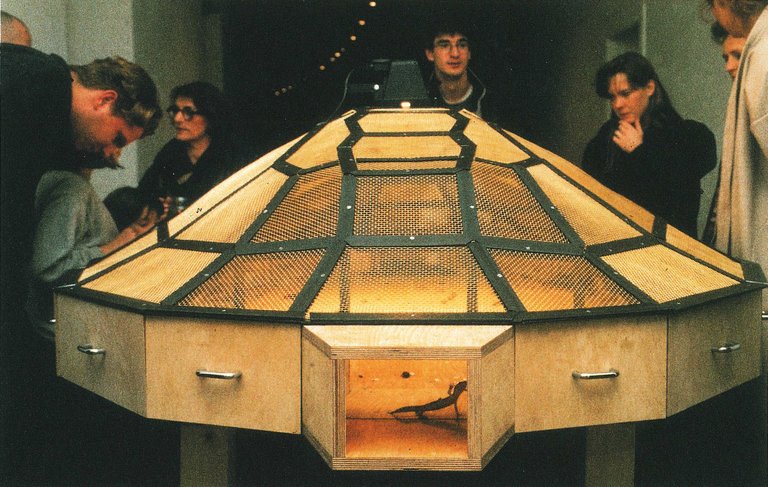

The only piece in the exhibition involving live creatures is Theater of the World (1993), where insects are likely to be consumed by larger animals. Asking for the removal of a piece that replicates what naturally happens between species and where the only animals harmed are insects that are bred to be fed to pets, suggests that the artistic representation of that process is always gratuitous because art is merely an “entertaining indulgence.”

While art can be indulgent or entertaining, this certainly does not characterize the work of Chinese conceptual artists of the 1990s. By exploring taboos and testing the boundaries of the permissible, their art reveals the brutality within the oppressive conditions of living in an authoritarian system and dealing with the massive displacements brought on by globalization.

By daring to face dark aspects of existence and represent them in all their stark cruelty, art can provide necessary insights into realities that are difficult to face. This is the type of art that censorship always targets, and it is this art that needs the most vigorous defense.

Hunter O’Hanian

Executive Director

College Art Association

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO

Index on Censorship

Chris Finan, Executive Director

National Coalition Against Censorship

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1506934535855-de4d7b28-9d4b-5″ taxonomies=”15469″][/vc_column][/vc_row]