Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

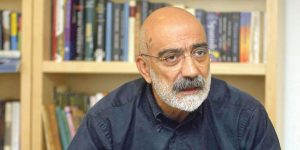

Turkish authorities re-arrested the internationally known Turkish novelist Ahmet Altan just one week after his release from more than three years in detention. Index on Censorship and 24 other NGOs say that his re-arrest, on 12 November, was an extraordinarily low blow in a case that has been marked by political interference and arbitrariness from start to finish.

In addition to ongoing violations of his right to freedom of expression, stemming from a prosecution that should never have been brought in the first place, his re-arrest is a form of judicial harassment. Altan should be immediately released and his conviction vacated, the organisations say.

On 4 November this year, Altan was convicted of “aiding a terrorist organisation without being its member” and sentenced to 10 years and six months in jail. He was released on bail pending appeal against conviction by the defence. Altan had originally been convicted of “attempting to overthrow the constitutional order” and sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. However, that conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court of Appeals who ordered a retrial on the lesser charge.

After the verdict in his retrial was handed down, the prosecutor appealed the decision to release him and on 12 November another panel of judges accepted this appeal and ruled that he should be re-arrested. Altan’s defence lawyers were not formally told of the court’s decision, but instead they learned about it through the pro-government media. Altan was detained later that evening and sent to Silivri Prison the following day.

Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights prohibits all arbitrary deprivation of liberty and the European Court of Human Rights has held that arbitrariness can arise where there has been an element of bad faith on the part of the authorities. Altan’s re-arrest and detention gives every appearance of being politically motivated, arbitrary, and incompatible with the right to liberty under Article 5. The organisations pointed to the following aspects of his re-arrest:

Thomas Hughes, executive director of ARTICLE 19 said: “The entire process of Ahmet Altan’s trial and retrial, including his prolonged detention, his release and then re-arrest on spurious grounds, has been completely arbitrary.

“The same court that convicted Altan of ‘attempting to overthrow the constitutional order’ then oversaw a retrial and convicted him of ‘aiding a terrorist organisation’, on the same evidence, which primarily consisted of Altan’s writings. That court then released him on bail and another court with no experience of the case ruled for his re-arrest.

“The case of Ahmet Altan is emblematic of the crackdown against writers and journalists in Turkey. Political revenge rather than justice has dominated the proceedings.”

Ahmet Altan’s case challenging his detention is still pending at the European Court of Human Rights. Other decisions by the ECtHR which are binding on Turkey and relate to prosecutions for free speech have had a significant impact on the outcome of the respective trials, including in the case of Ahmet’s brother, Mehmet Altan.

A ruling from the European Court setting out the scope and nature of the violations in Ahmet Altan’s case would likely have a decisive impact on his detention and the appeals process in his case.

We repeat our call for the Turkish authorities to release Ahmet Altan and vacate the conviction against him. The Turkish authorities should cease all judicial harassment of individuals on the basis of their political opinions and for exercising their fundamental right to freedom of expression.

Signatories:

ARTICLE 19

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Amnesty International

Articolo 21

Cartoonist’s Rights Network International (CRNI)

Danish PEN

English PEN

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

German PEN

Human Rights Watch

IFEX

Index on Censorship

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

International Press Institute (IPI)

Norwegian PEN

Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa

PEN America

PEN Canada

PEN International

P24, Platform for Independent Journalism

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

Swedish PEN

World Association of News Publishers (WAN-IFRA)

Background

Ahmet Altan is an internationally known Turkish novelist who was convicted to life imprisonment without parole in February 2018 for “attempting to overthrow the constitutional order” in an unfair trial that primarily relied on his writings and comments in the media. His case was overturned by the Supreme Court of Appeals in July, who recommended a retrial on equally bogus charges of “aiding a terrorist organisation without being its member”. On 4 November this year, Altan was convicted on the new charges and sentenced to 10 years and six months in prison. He was released on bail pending appeal, after having served more than three years in detention, awaiting trial or appeal. On 12 November he was returned to prison, just one week after his release.

In its verdict on 4 November, the judge ruled that the parliament and the presidency could not intervene in the case as victims. Despite this, on 5 November parliament made an application challenging, inter alia, Altan’s release. It also made a separate application challenging the verdict.

On 6 November, the prosecutor also challenged the decision to release Altan on the grounds that there was a flight risk, despite the fact that a foreign travel ban had been put in place.

On 7 November, Istanbul Heavy Penal Court No 26 reviewed the legal challenges and confirmed its previous decision to release him and the case file was referred to the Heavy Penal Court No 27 for review.

On 8 November, the presidency challenged the verdict, including the release of Altan, stating that all defendants should be charged on the basis of the initial indictment.

On 11 November, the presiding judge and prosecutor of Heavy Penal Court No 27 were changed.

On 12 November, the court, with a new judge and prosecutor, reviewed the legal decision of Court No 26 and issued a ruling. The ruling was not provided to the defence lawyers, but was leaked to the pro-government press which immediately reported that an arrest warrant had been issued. Ahmet Altan was re-arrested that evening, before the decision was communicated to him, or his lawyers, officially.

On 13 November, Altan was taken before the presiding judge at Heavy Penal Court No 27 to review his arrest and decide on his transfer to prison. The judge ruled that he should be returned to prison.

Note: ARTICLE 19 submitted an expert opinion to the court during the first trial, which examined the coup-related charges and evidence against international standards on the right to freedom of expression. Human Rights Watch also assessed the indictment and, like ARTICLE 19, found that the journalistic works cited expressed political opinions and did not incite or advocate violence. No new evidence was presented at the retrial on terrorism charges.

UPDATE: Index on Censorship is delighted to learn of the news that Ahmet Altan and Nazlı Ilıcak have been released from prison and that Mehmet Altan has been acquitted and released.

We nonetheless remain concerned that Altan and Ilıcak were convicted and are on probation, and that their co-defendants — Fevzi Yazıcı, Yakup Şimşek and Şükrü Tuğrul Özşengül — remain in detention after having been convicted of “membership of a terrorist organisation”.

Ahead of the second hearing in the retrial of Turkish novelist Ahmet Altan, Nazlı Ilıcak and four other journalists and media workers, Article 19 and 16 free speech and human rights organisations call for all detained defendants to be released and for the charges to be dropped. We believe that the charges against Altan and the other defendants are politically motivated and the case should never have gone to trial. We believe that the new charges are also bogus, as no credible evidence has been presented linking the defendants to terrorism.

Altan and Ilıcak have been in pre-trial detention for over three years on bogus charges. They were initially charged with sedition and are now being re-tried on terrorism charges following a decision by the Supreme Court of Appeals. The final prosecutor’s opinion has been published ahead of the hearing on Monday 4 November, revealing that the prosecutor will ask for the judge to sentence significantly above the minimum required sentence for these offences. If the judge rules in line with the Prosecutor’s opinion, this will mean that the defendants will remain in detention during the appeals process which could take many more months. The on-going violation of their rights is a damning indictment of the state of Turkey’s judicial system, which has been placed under immense political pressure since the failed coup of July 2016.

We have serious concerns regarding the panel of judges overseeing this retrial. It will be presided over by the same judge who oversaw the first trial, which involved several violations of the right to a fair trial and according to the Bar Human Rights Committee, “gave the appearance of a show trial”. The same panel of judges also previously refused to implement the Constitutional Court and European Court of Human Rights rulings that Mehmet Altan’s rights had been violated by his pre-trial detention, sparking off a constitutional crisis.

With the Constitutional Court failing to find a violation in the case of Ahmet Altan and Nazlı Ilıcak in May 2019, we look to the European Court of Human Rights (the Court) for justice. In 2018, the Court found several violations of Mehmet Altan’s rights. The Court also said that it would keep the effectiveness of remedies before the Constitutional Court under review. Altan and Ilıcak have now spent over three years in pre-trial detention. If the judge rules on Monday in line with the Prosecutor’s final opinion, they will be condemned to an even longer period of unjustified detention. By January 2020, their applications before the Strasbourg Court will have been pending for three years. A judgment from the European Court of Human Rights on their cases is now crucial.

Signatories

Article 19

Articolo 21

Danish Pen

English Pen

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

Freedom House

German Pen

Global Editors Network (GEN)

IFEX

Index on Censorship

Norwegian Pen

P24 – Platform for Independent Journalism

Pen America

Pen Canada

Pen International

South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

Swedish Pen

About the case

The retrial in the case of writers and media workers Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan, Nazlı Ilıcak, Yakup Şimşek, Fevzi Yazıcı and Şükrü Tuğrul Özşengül began on 8 October 2019, after the Supreme Court of Appeals overturned their convictions of “attempting to overthrow the constitutional order through violence and force” under Article 309 of the Turkish Penal Code, for which they had been given aggravated life sentences. The Supreme Court of Appeals found that there had been no evidence of their use of “violence and force” and that Mehmet Altan should be acquitted entirely due to lack of sufficient evidence. The charges for the other five defendants were reduced: Ahmet Altan and Nazlı Ilıcak face new charges of “aiding a terrorist organisation” while Yakup Şimşek, Fevzi Yazıcı, Şükrü Tuğrul Özşengül face charges of “membership in a terrorist organisation”. Their re-trial, on new charges, began in October 2019 and the second hearing, at which the judge may rule on the case is on November 4, 2019.

More detailed information on these cases and the retrial can be found here

ARTICLE 19 submitted an expert opinion to the court in June 2018: https://www.article19.org/resources/turkey-article-19-submits-expert-opinion-in-the-case-of-brothers-ahmet-and-mehmet-altan/

Freedom of expression in Turkey

Under President Erdogan’s rule, freedom of expression has severely declined in Turkey. Over the last four years, at least 3,673 judges and prosecutors have been dismissed and the judiciary effectively purged of anyone who is perceived as opposing the government through the exercise of freedom of expression. Around 170 media outlets have been closed down over claims they spread “terrorist propaganda”. Only 21 of these have been able to reopen, some of them however being subject to major changes in their management boards. Turkey has become the world’s biggest jailor of journalists with at least 121 journalists and media workers currently in prison and hundreds more on trial.

For more information on freedom of expression in Turkey, please see our joint NGO submission for Turkey’s Universal Periodic Review at the United Nations

https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Turkey-UPR-submission_July2019.pdf

CONTACT

For further information Pam Cowburn, [email protected], 07749 785 932.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Ahmet Altan is one of over 150 journalists who is in detention in Turkey. Altan stands accused of “attempting to overthrow the government” and “attempting to eradicate the parliament” and they face three counts of life sentences without the possibility of parole.

Ahmet Altan is one of over 150 journalists who is in detention in Turkey. Altan stands accused of “attempting to overthrow the government” and “attempting to eradicate the parliament” and they face three counts of life sentences without the possibility of parole.

Altan, who testified on 19 September through the judicial teleconferencing system from Silivri Prison, mainly addressed the presiding judge. The next hearing in his case will take place on 13 November.

The belief that makes people gather around a religion is rooted in their trust in the honesty of God.

God cannot tell lies.

Lying would deprive God of his divinity.

In ancient times, even a pagan tribe that worshipped a pear tree believed in the tree’s honesty; that it would bear the promised fruit at the promised time.

Ever since people were created they have gathered around authority, worshipped it and entrusted themselves to it.

People who don’t trust each other, who divide into groups, tribes, and clans, can only come together around an authority which they trust to be honest.

In the same way that a person needs an honest authority in order to become religious, there is need for an honest authority in order for millions of people to become a nation and establish a state.

The honest authority which enables the millions to turn into a nation and establish a state is not one of politicians, soldiers, executives, or political parties.

That honest authority, that great source of trust, resides in the judges.

The magical link that turns millions of dispersed pearls into a necklace is the honesty of those judges.

Without judges, there cannot be a nation. Without judges, there cannot be a state.

What makes a nation and what makes a state is its judges.

In the same way that removing the oxygen atom from a water molecule turns the very source of life into one of death, removing the judges from the state turns it into an armed gang.

If there are no judges then there is no state.

When you remove the oxygen atom from a water molecule it no longer qualifies as water. Similarly, when you remove the judges from the state, the state no longer qualifies as a state.

What distinguishes a state from an armed gang is the presence of judges.

Well, then what makes this ever so vitally important judge a judge?

It is not his or her diploma, his or her cloak, his or her podium.

What makes a judge a judge is their possession of an almost godly honesty and the people’s undoubting belief in that honesty.

In the same way that there cannot be a lying God there cannot be a lying judge.

A judge would lose their qualification as judge the moment they were to lie in court.

If a state were to allow a judge who no longer qualifies as a judge to continue, that state would no longer qualify as a state.

A judge demolishes the state as they demolish their qualification as a judge by lying in court.

A year ago, Mehmet Altan and I were arrested on the charges of “giving subliminal messages to the putschists.”

Later on, this ridiculous allegation disappeared and we were sent to prison on the charges of staging the coup on 15 July and attempting to overthrow the government with weapons.

We are said to have staged an armed coup d’état.

This is the crime we are charged with.

This is a case in which the absurdity of the allegation overwhelms even the gravity of the charges.

Now, I’ll say something loud and clear to this court, to this country and to those around the world who have taken an interest in this trial:

Show us even a single piece of concrete evidence of the strange allegations against us, and I will not defend myself anymore. Even if I am sentenced to the gravest penalty I will not appeal the ruling.

I am saying this loud and clear.

Show me a single piece of evidence and I will waive my right to appeal.

I will submit to spending the rest of my life in a prison cell.

During this past year, which we spent in prison, a judge ruled each month for the continuation of our imprisonment by claiming that “there was solid evidence” against us.

In the previous hearing, you, too, said there was “concrete evidence” against us.

Now, for you to be able to preserve your integrity and your qualification as a judge and for the state to be able to preserve its qualification as a state, you need to show us what those pieces of “solid evidence” are.

Since you declared with such ease that there was solid evidence, that evidence needs to be in our case files.

Come on, show that solid evidence to us and to the rest of the world – the evidence which proves that we staged a coup on 15 July.

You won’t be able to show it.

Both you and I know that there is no such evidence.

Because these allegations are utter lies.

Go ahead, disprove what I have been saying, pull out that piece of evidence and show it to us.

There are some difficult aspects to arresting people on nonsensical allegations, Your Honour, and now you are confronted with those difficulties.

Either you will end this nonsense by saying “there is no solid evidence” or you will show us some “solid evidence.”

Or, you will insist on saying “there is solid evidence” while there is no solid evidence and thus lose your integrity and your qualification as a judge?

And with you, the state will lose its qualification as a state.

Thereby we will cease to be defendants.

We will become hostages of the judges, who have lied and therefore lost their qualification as judges, and to an armed gang, which has lost its qualification as a state.

Because in a real state with real judges there can be no allegation without evidence, there can be no trial without evidence, there can be no arrest without evidence.

Because a state, if it is to be a state, needs evidence to put a person on trial.

Only armed despots lock people away without evidence.

If you continue trying and incarcerating us without evidence you will demolish the judiciary and the state.

You will be committing a serious crime.

Turkey will turn into a jungle of thuggery and despotism, where the guilty try the innocent.

Now, you need to decide whether you are an honest judge or a criminal.

If you accept an indictment that makes such absurd allegations and declare “there is solid evidence” while there isn’t even a single piece of evidence, you’ll discover life’s capriciousness and will put yourself on trial while thinking you are trying us.

I wait for your decision.

As an aged writer, one much more experienced than you are, my advice to you is to save yourself, save your profession, and save your state.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1507033820060-8b45a65c-3de0-8″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91904″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Two of Turkey’s most prominent writers, brothers Ahmet and Mehmet Altan, were sentenced to life in prison on Friday 16 February 2018.

Convicted on groundless charges related to the attempted coup in 2016 against the government led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, these verdicts, the first of their kind, set a devastating precedent for the many other journalists and writers in Turkey who are being tried on similarly spurious charges widely believed to be politically motivated to silence all criticism of Erdoğan.

Since they began last July, I have been present to observe the Altans’ trial and to witness extraordinary violations of due process and the defendants’ rights to a fair trial. They are also emblematic of an unprecedented crackdown on critical voices in a country where the rule of law is in free fall.

The brothers were arrested in the aftermath of the coup attempt under a state of emergency imposed by Erdogan in July 2016 and renewed six times since, which gave him sweeping powers and pushed Turkey closer to authoritarianism. It is hard to overstate the extent of the purge that has taken place: 200 journalists and 50,000 individuals have been arrested. Independent mainstream media have been all but silenced, with over 180 media outlets and publishing houses closed down. Over 150,000 civil servants, journalists and academics, have been summarily dismissed with no effective appeals process or prospect of re-employment. Dozens of the dismissed have committed suicide.

Once arrested, the Altans found themselves in a legal system where the rule of law has been dismantled with terrifying speed since the coup attempt. What judicial independence existed previously was eviscerated as 4,200 judges and prosecutors were summarily dismissed and replaced with political appointees. The legal system itself – parts of which have long been used to judicially harass independent voices – has been transformed wholescale into a system of repression, with the judiciary now playing a central role in the deterioration of free speech and the rule of law itself.

The indictment in the Altans’ case is 247 pages long, and was largely copied and pasted from other indictments, evidenced by a name from another trial mistakenly appearing in the document. The brothers initially faced three consecutive life terms on charges of plotting to overthrow the government, parliament and the constitutional order for their alleged links to a network led by Fethullah Gülen whom the government accuses of orchestrating the attempted coup. These charges were subsequently reduced to just the latter, carrying one ‘aggravated’ life sentence: a sentence without prospect of parole. Like scores of other journalists across the country, the Altans are also accused of supporting multiple additional terrorist groups – groups which are themselves even in conflict with one another.

Throughout the trials there has been scant evidence or detail of the criminal acts the Altans are said to have committed. A key part of the case has centred on their participation in a TV programme on 14 July 2016, the day before the coup attempt, during which they are said to have sent “subliminal messages” to the coup plotters. (In fact, they discussed the fact that there would be elections and that Erdogan might be voted out.) After this “evidence” was ridiculed wholesale in the Turkish media, it was dropped. In a similarly farcical use of evidence, six $1 bills found in Mehmet Altan’s apartment are cited as proof of his support for the coup, though how these could possibly contribute to attempting to overthrowing the constitutional order remains unclear.

Leading QC, Pete Weatherby, characterised the proceedings as a “show trial” in a report for English Bar Human Rights Committee. At a hearing in November 2017, the judge abruptly expelled the entire defence team. Mehmet Altan was left to defend himself with no lawyer present. I had the surreal experience of observing that hearing with his defence team from the court cafeteria via Twitter. On Monday of this week, his lawyer was expelled from court once again, this time for insisting that the recent landmark Turkish Constitutional Court decision on his client’s case be included in the court’s record, to say nothing of it being upheld.

The lower court’s decision to defy this constitutional court decision on Mehmet Altan is itself at the heart of a constitutional crisis unfolding in Turkey. Until 11 January 2018, the constitutional court had exempted itself from deciding any State of Emergency related cases, despite the 100,000 applications pending before it. Then in a landmark decision a month ago, the constitutional court ruled 11-6 that the detention of Mehmet Altan and veteran journalist, Sahin Alpay for over a year constituted violations of their constitutionally protected “right to personal liberty and security” and “freedom of expression and the press”, establishing the way for their immediate release and setting the necessary precedent for the releases of the dozens of other jailed journalists.

In the hours following the decision, however, a criminal court in Istanbul defied the constitutional court ruling declaring the judgement was a “usurpation of authority” and therefore could not be accepted. This language was disturbingly similar to the reaction of the deputy prime minister and government spokesperson, Bekir Bozdağ, who had tweeted this objection to the decision, claiming that the Constitutional Court had “exceeded” its authority.

This political interference was blatantly in violation of the Turkish Constitution, which renders all constitutional court decisions binding on lower courts. The ongoing crisis surrounding the rule of law and separation of powers, which has been growing since the imposition of the state of emergency, has reached its nadir with Friday’s verdict against Mehmet Altan, demonstrating that Turkey’s citizens can have no expectation of an independent or effective legal remedy in their country.

This crisis in Turkey has profound implications for the European human rights system. The Altans’ case, along with those of eight others relating to journalism is pending before the European Court of Human Rights, of which Turkey has been a member since 1954. Their lawyers applied to the European court in November 2016 after continued inaction by the Turkish Constitutional Court and in April 2017, the court accorded priority status to the cases, opening the way for accelerated proceedings. So important are the implications of these cases for freedom of expression in the country as a whole that an unprecedented group intervened before the court including the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and a coalition of international human rights NGOs led by PEN International.

Since those interventions, however, the European court has been silent. As there is no expectation of independent or effective justice in Turkey, Strasbourg is the last hope for justice for the writers – and indeed, for Turkish society as a whole. And there can be no more urgent cases than these for the European court: they concern individuals who have been detained for over eighteen months, solely on the basis of their writing, that is to say for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression and opinion, which is guaranteed under the European Convention of Human Rights, of which the court is guardian.

However, many in Turkey fear that politicking at the highest levels between Turkey and European member states and institutions is delaying this judgement. Indeed it is widely felt that Europe’s relative silence on the journalists cases is provoked by more utilitarian concerns: the EU-Turkey refugee deal for one, military interests in Syria for another. Meanwhile, Theresa May has shown she is more concerned about selling Erdogan fighter jets and securing a post-Brexit free trade agreement than promoting democracy or human rights.

Meanwhile, the European Union and May appear to be sacrificing the very people who have fought for democratic and liberal values in Turkey. One of the great privileges of my time observing these cases over the last 18 months has been to witness historic defences of freedom of expression from journalists in the dock, on trial for their lives for daring to criticise authoritarianism, corruption and human rights abuses. I think of Ahmet Altan’s defiant closing statement to the judge in the prison court this Tuesday, surrounded by 30 heavily armed riot police – “I came here not to be judged but to judge. I will judge those who, in cold blood, killed the judiciary in order to incarcerate thousands of innocent people.”

Europe would do well to take a longer-term view, to uphold the values of democracy and human rights lest we lose Turkey outright to authoritarianism. Political pressure does work: On the same day as the Altans were sentenced, the Turkish-German journalist, Deniz Yucel, was released after a year in detention following talks between German Chancellor Merkel and Turkish PM Yildirim. Political pressure from Germany is also widely credited for the release of ten human rights defenders and Amnesty International staff in October 2017. Much more of this pressure is needed. Other countries like the UK, and political and financial institutions including the EU need to step up and demonstrate the values they profess to hold in their relations with Turkey.

We urge Europe not to abandon the Altans and Turkey’s other jailed journalists. We can only hope for Turkey’s democrats that justice does not come too late. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”3″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1519806559338-3ec987ef-0828-8″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]