Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The second cohort of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board was announced today. The members will discuss topical freedom of expression events, participate in #IndexDrawtheLine debates and advise Index on youth issues. The new board will sit from December 2014 to May 2015.

Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board:

Abishek Phadnis

Abishek Phadnis

Abhishek recently completed a Master’s in Diplomatic History from the London School of Economics, and is due to commence doctoral research on an early history of the Indian nuclear weapons programme. As a secularist activist and a fierce campaigner against theocratic censorship in England, he has been honoured by the British National Secular Society for “bravely challenging Islamist groups, his own university (LSE) and Universities UK over important and fundamental issues such as free speech.

Ásta Helgadóttir

Ásta Helgadóttir

Ásta is a deputy member of the Icelandic Parliament for the Icelandic Pirate Party and will take position as an MP in the fall of 2015. Her interest in censorship is both political and academic, mainly focused on the aspects of European legal justifications regarding modern day technological censorship.

Catarina Demony

Catarina Demony

Catarina is the founder of The Voiceless, a media platform about human rights violations, and recently graduated from Kingston University with a Journalism degree. Currently, she works in the communications team at London School of Economics Students’ Union, as well as University of the Arts. Catarina also works closely with Amnesty LDN, part of Amnesty International movement for recent graduates and young professionals.

Jordan Mitchell

Jordan Mitchell

Jordan is a human rights advocate, writer, and Truth About Youth associate working with Ovalhouse Theatre. Based in London, he believes it is imperative for the under-represented to be given a platform, with a particular focus on the role of the media.

Kay Robinson

Kay Robinson

Kay is studying History and Politics at Lancaster University, and is sub-editor for the International Political Forum. A strong supporter of human rights, she believes that free and equal platforms of expression have a crucial role in forming safe, empowered societies.

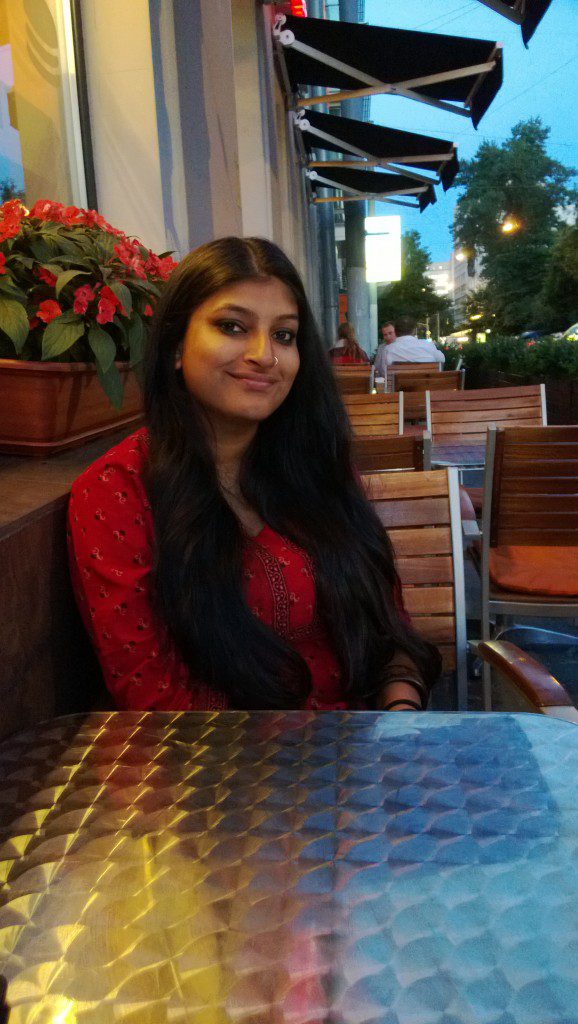

Mahima Singh

Mahima Singh

Mahima works for newslaundry.com, an independent media website in India. Mahima believes that the freedom of expression is one of the core fundamentals of a healthy society . She has been advocating freedom since her college days when she was forced to take down a story she had written because it upset the authority.

Mari Shibata

Mari Shibata

Mari is a freelance newsgatherer for AP Television, a BFI-funded filmmaker and ocassional writer for Vice. Also a Cambridge University graduate in music, she is passionate about issues surrounding free expression in the cultural arts from conflict zones.

Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary

Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary

Mohanad is an Egyptian Engineering major in the Middle East. With the Arab uprisings over the last few years, his passions for freedom of expression and human rights were further consolidated. Mohanad is currently secretary, editor and founding member at a university club called ‘Fikir’ (meaning ‘thought’) that aims to encourage social involvement and responsibility.

The application period for the next youth board will open in May 2015 for the June to November cohort.

What is the youth board?

The youth board is a specially selected group of young people aged 16-25 who will advise and inform Index on Censorship’s work, supporting our ambition to fight for free expression all around the world and ensuring our engagement with issues relevant to tomorrow’s leaders.

Why has Index started a youth board?

Index on Censorship is committed to fighting censorship not only now, but also in future generations, and we want to ensure that the realities and challenges experienced by young people in today’s world are properly reflected in our work.

Index is also aware that there are many who would like to commit some or all of their professional lives to fighting for human rights and the youth board is our way of supporting the broadest range of young people to develop their voice, find paths to freely expressing it and potential future employment in the human rights/media/arts sectors.

What does the youth board do?

Board members meet once a month via Google Hangout to discuss the most pressing freedom of expression issues of the moment and to set a monthly question for our project, Draw the Line. You will be expected to write a minimum of 1 blog post introducing/concluding the question of the month and to help us spread the word about Index.

There is also the opportunity to get involved with events such as debates and workshops for our work with young people and also events such as our annual Index Freedom of Expression Awards and Index magazine launches.

How do people get on the youth board?

Each youth board will sit for a term of 6 months.

Current board members are invited to reapply up to one time.

The board will be selected by Index on Censorship in an open and transparent manner and in accordance with our commitment to promoting diversity.

Why join the Index on Censorship youth board?

You get the chance to be associated with a prestigious media and human rights organisation and have the opportunity to discuss issues you feel strongly about with Index and with other amazing young people (internationally). At each Board meeting we will also give you the chance to speak to someone senior within Index or the media/human rights/arts sectors, helping you to develop your knowledge and extend your personal networks and you’ll be featured on our website.

Index on Censorship held its latest Draw the Line workshop with the young associates of Ovalhouse theatre in south London. The young associates are the theatre’s steering group for the national Truth about Youth initiative, which aims to challenge and change negative perceptions about young people, by supporting projects which enable them to work with adults, the media and the wider community. The group individually explored different freedom of expression issues before examining this month’s question “Do laws restrict or protect free speech?” in more detail as a group.

Young Associate Jordan Mitchell shares his experience of the workshop:

Going into the freedom of expression workshop, I had a couple of questions in mind; who defines freedom? Does freedom mean something different to each person? And how do we draw the line between free expression and infringing on another person’s freedom and sense of self? As a young associate, my colleagues and I are actively involved in the community, and one of the things we encourage and are encouraged to do ourselves is to appreciate different opinions, and respect that everyone has the right to that opinion.

The exercises were informative and engaging, particularly the “belief scale” (this involves being given a statement and having to answer how far you agree/disagree by positioning yourself on an invisible line across the room with either end representing “agree” or “disagree”). Often the questions posed to us led to a spread across the scale, which showed how varied opinions can be, even in a group containing people with similar interests. The great thing about it was that the reasoning put forward by people was incisive, and even if my view didn’t change, I understood and accepted that point of view.

One thing was reaffirmed in my mind at the end. Freedom of expression is limited dependent on who you know. Influence plays a big part, and tying in with the work that we do as young associates, something has to be done to build more platforms for people to be heard.

This article was originally posted on 28 October at indexoncensorship.org

Eurovision contestant Teo, in the music video for this year’s Belarusian entry Cheesecake (Image: Yury Dobrov/YouTube)

If you want a Eurovision of the future, imagine a faux-dubstep bassline dropping on a human falsetto, forever. That was how it felt watching YouTube footage of this year’s entrants in the continent’s greatest song-and-dance-spectacle.

The Eurovision Song Contest, born of the same hope for the future and fear of the past as the European Union, is approaching its 50th year. And strangely, it’s doing quite well. In spite of fears that the competition would end up as an annual carve up between former Soviet states, recent years have in fact seen a fairly equal spread of winners throughout the member states of the European Broadcasting Union (who do not actually have to be in Europe; a fact often missed by anti-Zionists who somehow see a conspiracy in the fact that Israel is a regular entrant in the competition is that channels in countries such as Libya, Jordan and Morocco are also members of the EBU, and technically could enter if they wish. Morocco did, in 1980). Since 2000, the spread of winners between Western Europe, the former Soviet states, and the Balkans and Turkey have been pretty much even.

While some of the geopolitics will always be with us — Turkey and Azerbaijan united in their hatred of Armenia, Cyprus and Greece douze-pointsing each other at every opportunity — the once-derided contest has in fact functioned as a genuine competition. Year in, year out, the best song in the competition tends to win, while the laziest entrants, not taking the event seriously as a songwriting competition (yes, we’re looking at you, Britain), tend to fall behind and then complain that Europe doesn’t “get” pop music.

The best songs and singers triumph, by and large. But Eurovision still does have a political edge.

Take Tuesday’s semi-final in Copenhagen. Russia’s entry, Shine, performed by the Tolmachevy Sisters and described by Popbitch as sounding like “almost every Eurovision song you’ve ever imagined” contained some unintentionally ominous lines:

Living on the edge / closer to the crime / cross the line a step at a time

Add an “a” to the end of that “crime”, and you’ve got the Kremlin’s current foreign policy neatly summed up in a single stanza.

I am not suggesting that the Tolmachevys were sent out to justify Putin’s expansionism. Nonetheless, the Copenhagen crowd were keen that Russia should know what the world thought of its foreign policy and domestic human rights record: as it was announced that Russia had made Saturday’s grand final, the arena erupted in jeering. The dedicated Eurovision fan is clearly not just a poppet living in a fantasy world of camp. They are engaged with the world, and particularly the regressive policies of countries such as Russia, Azerbaijan and Belarus, perhaps more so than your average European.

When Sweden’s Loreen won the competition in Baku, capital of Azerbaijan, in 2012, she pledged to meet the country’s human rights activists. That same year, BBC commentator “Doctor Eurovision” (he actually is a doctor of Eurovision) made explicit references to Belarus’s disgraceful dictatorship, rather than simply giggle at the funny eastern Europeans.

This raises an interesting question about how we engage with dubious regimes.

Before the Baku Eurovision in 2012, there was some discussion over whether democratic countries should boycott the competition, sending a message to Aliyev’s regime.

“No,” Azerbaijani civil rights activists told Index on Censorship. “Let the world come and see Azerbaijan.” They felt that for most of the world, most of the time, they are citizens of a far away country of whom we know nothing. They wanted to take their chance while the world was looking. I think they got it right. As discussed last week, Azerbaijan is engaged in a massive international PR campaign, but to most people in the world since that Eurovision and the attention it raised for the country’s opposition, it has not been able to entirely disguise its atrocious record on free speech and other rights.

On Friday, the International Ice Hockey Federation’s world championship will open in Belarus. Though there was some discussion of boycotting that event, it has died down. Nonetheless, journalists from Europe and North America will be covering the event, and fans will travel too.

Belarus’s macho dictator Alexander Lukashenko is a keen ice hockey fan, and will be aiming to sweep up the glory of hosting a major international sporting event, not long after the country hosted the world track cycling championships in 2013.

Ice hockey fans and sports journalists are generally not the type of people who go in for Eurovision. But maybe they should try to take a leaf out of the Song Contest supporters book. Have a look at the country around them, learn a little about the politics, and spread the word about the side the dictators don’t want us to see.

Autocrats try to use these international competitions to control the world’s view of them. We should beat them at their own games.

This article was posted on May 8, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

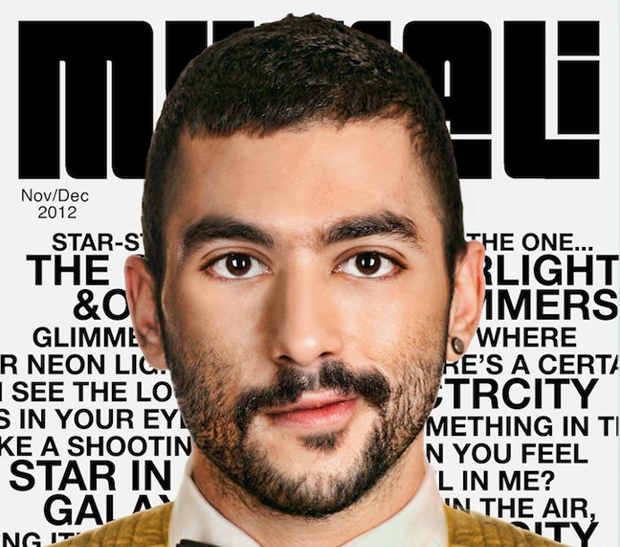

Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, is the lead singer of Mashrou’ Leila

While walking the streets of the upscale downtown district of Beirut, or sipping cocktails in one of El-Hamra’s bustling bars, one could easily forget that Lebanon is a country where civil liberties are still in debate.

Article 534 of the Lebanese penal code states: “Any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature is punished by imprisonment for up to one year.” The vaguely worded article has and is still being used to crackdown on the LGBT community in Lebanon. Compared to its neighbours in the Middle East, Lebanon has long been considered one of the least conservative countries in the region. According to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2013, 18% of the Lebanese population thinks that homosexuality should be accepted in the society, putting it way ahead of Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia where almost 97% of the population views homosexuality as deviant and unnatural.

The Lebanese Psychiatric Society issued a statement in early 2013 saying that: “The assumption that homosexuality is a result of disturbances in the family dynamic or unbalanced psychological development is based on wrong information” — making Lebanon the first Arab country to dismiss the belief that homosexuality is a mental disorder. On 28 January 2014, Judge Naji El Dahdah of Jdeideh Court in Beirut dismissed a claim against a transgender woman accused of having a same-sex relationship with a man, stating that a person’s gender should not simply be based on their personal status registry document, but also on their outward physical appearance and self-perception. The ruling relied on a 2009 landmark decision by Judge Mounir Suleimanfrom the Batroun Court that consenual relations can not be deemed unnatural. “Man is part of nature and is one of its elements, so it cannot be said that any one of his practices or any one of his behaviours goes against nature, even if it is criminal behaviour, because it is nature’s ruling,” stated Suleiman.

Despite the recent positives, being gay in Lebanon is still a taboo. In a country drenched in sectarianism, debates about homosexuality are easily dismissed in the name of religion and homosexuals are accused of promoting debauchery.

“People in Lebanon, and across the region, still act like homosexuality doesn’t exist in our society,” said Kareem, who requested that Index only use his first name. “I think it’s important that we start the conversation and get the issues out in the open, so people can start acknowledging it and then decide their stance on. The fight for our rights comes later on,” he added.

In 2013, Antoine Chakhtoura, mayor of the Beirut suburb of Dekwaneh, ordered security forces to raid and shut-down Ghost, a gay-friendly nightclub. “We fought battles and defended our land and honor, not to have people come here and engage in such practices in my municipality,” the mayor asserted.

Four people were arrested during the raid and brought back to municipal headquarters where they were subject to both physical and verbal harassment: forced to undress, enact intimate acts which included kissing, as well as being violently beaten. Marwan Cherbel, minister of interior at the time of the incident, backed the mayor’s actions, adding that: “Lebanon is opposed to homosexuality, and according to Lebanese law it is a criminal offence.”

Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. In a similar raid on a movie theatre in the municipality of Burj Hammoud known to cater for a gay clientele, 36 men were arrested and forced to undergo the now abolished anal probes — known as tests of shame. The raid came only a few months after Lebanese TV host Joe Maalouf dedicated an episode of his show Enta Horr (You’re Free) to exposing a porn cinema in Tripoli where it was claimed that young boys were being sexually abused by older men.

“The fact that these incidents received a lot of media coverage, some of which denounced the raids, is a sign that the public is little by little taking an interest in the issue of gay rights,” said Kareem. “Five or six years ago, this could have easily gone unnoticed. While the gay community might not be fully accepted or tolerated in Lebanon, it has been gaining a lot more visibility in recent years.”

Helem, a Beirut-based NGO, was established in 2004 to be the first organisation in the Middle East and Arab world to advocate for LGBT rights. In addition to campaigning for the repeal of Article 543, Helem offers a number of services, including legal and medical support to members of the LGBT community. Organisations like Helem and its offshoot Meem, a support group for lesbian women, had a huge impact on raising awareness and correcting misconceptions about homosexuality. Support from Lebanese public figures has also been on the rise in recent years. For example, popular TV host Paula Yacoubian and pop star Elissa have both shown support for the LGBT community in Lebanon via their Twitter accounts.

While the struggle to change the law continues, young artists have been challenging social norms through art. Mashrou’ Leila, a Beirut-based indie rock band, has sparked a lot of controversy thanks to their songs, in which they unapologetically sing about sex, politics, religion and homosexuality in Lebanon. In Shim el Yasmine, the band’s lead singer, Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, sings about an old love, a man whom he wanted to introduce to his family and be his housewife. Director and art critic, Roy Dib, recently won the Teddy Award for best short film in 2014 at the 64th Berlinale International Film Festival with his film Mondial 2010. The film tells the story of a gay Lebanese couple on the road to a holiday weekend in Ramallah, Palestine. It tries to explore the boundaries that make it impossible for a Lebanese person to go into Palestine, as well as the challenges faced by a homosexual couple in the region.

The battle for gay rights in Lebanon is multilayered, and while change is starting to feel tangible, there is still a lot to be done.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org