8 Oct 2015 | Campaigns, Mali, Press Releases

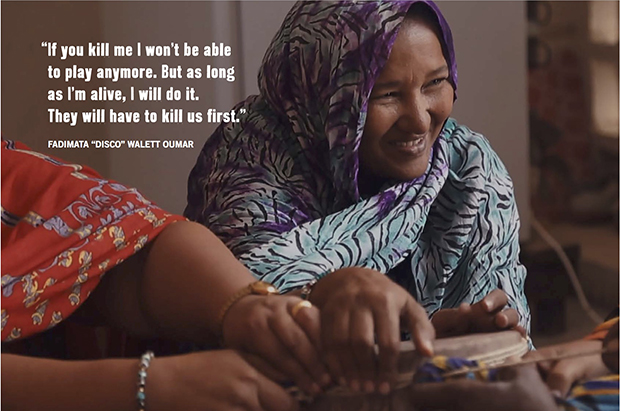

Fadimata “Disco” Walett Oumar, as featured in They Will Have To Kill Us First

Freedom of expression campaigners Index on Censorship and the producers of award-winning documentary They Will Have To Kill Us First are delighted to announce the launch of a new fund to support musicians facing censorship globally.

The Music in Exile Fund will be launched at the European premiere of They Will Have To Kill Us First: Malian Music In Exile – a feature-length documentary that follows musicians in Mali in the wake of a jihadist takeover and subsequent banning of music – at the London Film Festival on 13 October.

In its first year, the Music In Exile Fund will contribute towards Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship, which is a year-long structured assistance programme to support those facing censorship. The funds will be used to support at least one musician or group nominated in the arts category of the awards. This will include attendance at the awards’ fellowship week in April 2016 – an intensive week-long programme to support career development for the artists. This also brings training in advocacy, fundraising, networking and digital security – all crucial for sustaining a career in the arts when under the pressure of censorship. The fellow will also receive continued support during their fellowship year.

Songhoy Blues, who feature in They Will Have To Kill Us First, were nominated for the arts category of the Index Freedom of Expression Awards in 2015. Index’s current arts award fellow is Mouad Belghouat, a Moroccan rapper who releases music as El Haqed. His music publicises widespread poverty and rails against endemic government corruption in Morocco, where he is banned from performing publicly.

Johanna Schwartz, director of They Will Have To Kill Us First, said: “For the two years that followed the ban on music in Mali, I filmed with musicians on the ground, witnessing their struggles and learning what they needed in order to survive as artists. The idea for this fund has grown directly out of those experiences. When faced with censorship, musicians across the world need our support. We are thrilled to be partnering with our long-time collaborators Index on Censorship to launch this fund.”

Our ambition is to widen support as the fund grows to support more musicians in need.

You can donate to the Music In Exile Fund here.

For more details, please contact:

Index on Censorship: Helen Galliano – [email protected]

Mojo Musique: Sarah Mosses or Johanna Schwartz – [email protected]

8 Oct 2015 | About Index, Awards, Mali, mobile, News and features

Index is joining forces with the producers of a new feature-length documentary featuring Mali’s persecuted musicians to launch a fund that will offer support to musicians facing threats, violence, exile and criminal prosecution around the world.

In 2012, Muslim extremist groups captured northern Mali, implemented sharia law and banned all music. Radio stations were destroyed, instruments burned and Mali’s musicians faced torture, even death. They Will Have To Kill Us First: Malian Music In Exile tells the stories of the Malian musicians who fought back and refused to have their music taken away.

The Music In Exile Fund springs directly from witnessing the struggles of musicians featured in the film. The fund will contribute to Index on Censorship’s year-long Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship Programme, supporting at least one nominated musician or group by giving access to bespoke training and assist them to create, perform and share their work in a safe environment.

Songhoy Blues, who feature in They Will Have To Kill Us First, were nominated for the Index Arts award in 2015. The current Arts award fellow is Mouad Belghouat, a Moroccan rapper who releases music as ‘El Haqed’. His music publicises widespread poverty and rails against endemic government corruption in Morocco, where he is banned from performing publicly.

“For the two years that followed the ban on music in Mali, I filmed with musicians on the ground, witnessing their struggles and learning what they needed in order to survive as artists,” said Johanna Schwartz, director of They Will Have To Kill Us First. “The idea for this fund has grown directly out of those experiences. When faced with censorship, musicians across the world need our support. We are thrilled to be partnering with our long-time collaborators Index on Censorship to launch this fund.”

The fund will be launched at the film’s UK premiere at the British Film Institute on October 13.

“When we initiated the Awards Fellowship earlier this year, we wanted to help maximise the impact that our awards could have,” said Jodie Ginsberg, Index on Censorship chief executive. “We hope that this fund will allow us to do even more to assist those facing censorship so that can focus on what they do best: create.”

The funds will be used to support at least one musician or group nominated in the Arts award category. This will include attendance at the Awards Fellowship week in April 2016 – an intensive week-long programme to support career development for the artists. This includes training on advocacy, fundraising, networking and digital security – all crucial for sustaining a career in the arts under the pressure of censorship. The fellow will also receive continued support during their fellowship year.

Our ambition is to widen support as the fund grows to support more musicians in need.

You can donate to the campaign here.

7 Oct 2015 | Middle East and North Africa, mobile, Morocco, News and features

Index on Censorship Arts award winner 2015: Mouad ‘El Haqed’ Belghouat

Generally speaking, Arabic hip hop comes in two categories. There are rappers in the Gulf who like to brag about how great it is to be really, really rich. Then there are artists in places like Palestine and Algeria who use their work to talk about the endemic problems they face in their communities: disenfranchisement, discrimination, destitution and violence.

Index on Censorship Arts award winner Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat falls under the latter category. Hailing from Morocco, where the youth have been keen consumers of hip hop for many years, El Haqed has had a lot of attention since the Arab Spring. Rapping about poverty, police corruption and oppression in the country, the 24-year old has been felt the full force of the law. Arrested for the first time in 2011, he spent two years in prison before being arrested twice more because of his music.

Index spoke with El Haqed in June when he had just returned to Morocco in high spirits following a tour of Norway, Sweden and Denmark, and was looking forward to performing for the first time in his hometown of Casablanca. Unfortunately, the Moroccan state went to extraordinary lengths — blocking off roads and ordering an electricity company to shut off power — to ensure the concert didn’t go ahead. He is effectively banned from performing live or appearing on TV or radio.

Asked why the Moroccan government wants to silence him so badly, El Haqed said: “Because I continue to speak out against them and fight for freedom of expression.” On several occasions, the authorities have asked El Haqed to renounce his views. “They want me to say that we live in a democracy and that everything is OK, but I have always refused.”

An all too frequent but often unavoidable fact of life as an artist under siege is that there will be times when keeping a low profile seems necessary. While El Haqed is still writing and recording music, he isn’t currently posting to YouTube as he was before. “Publishing music at the minute would only cause more problems,” he explains. He adds, however, that this is only a temporary setback, and publishing on YouTube and to his tens of thousands of social media followers is very much a part of his future plans.

One area of extreme difficulty has been finding the right people — including a producer — to work with. El Haqed used to write music with other artists in Morocco, but this has become an inconvenience. “Musicians were told by the authorities to stop working with me, or they would be made to,” he says.

One area of extreme difficulty has been finding the right people — including a producer — to work with. El Haqed used to write music with other artists in Morocco, but this has become an inconvenience. “Musicians were told by the authorities to stop working with me, or they would be made to,” he says.

Although in the past El Haqed pushed the authorities to give him permission to perform in Morocco, he is resigned to the fact this may never happen. But there is hope. Visa applications pending, he has been invited to spend a week in Florence, Italy, in October for an exchange with Italian musicians, a debate on the music of the new generation and to perform in concert. A major focus of this visit will be to facilitate artistic collaboration.

He has also been invited to perform in Belgium in October by at the 25th anniversary of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights due to his being a “committed musician and human rights defender”.

Like one in five people his age in Morocco, El Haqed doesn’t currently have a job and relies heavily on family and friends for support. While it may be easier if he left Morocco to pursue a career in music, he has no intention of relocating.

“I love my country, and while I want to perform abroad, I will always come back to Morocco,” he says.

Index on Censorship demands Moroccan authorities end their harassment of El Haqed and allow him, and others like him, to perform in the country.

Nominations for the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards are currently open. Act now.

29 Jul 2015 | mobile, Morocco, News and features

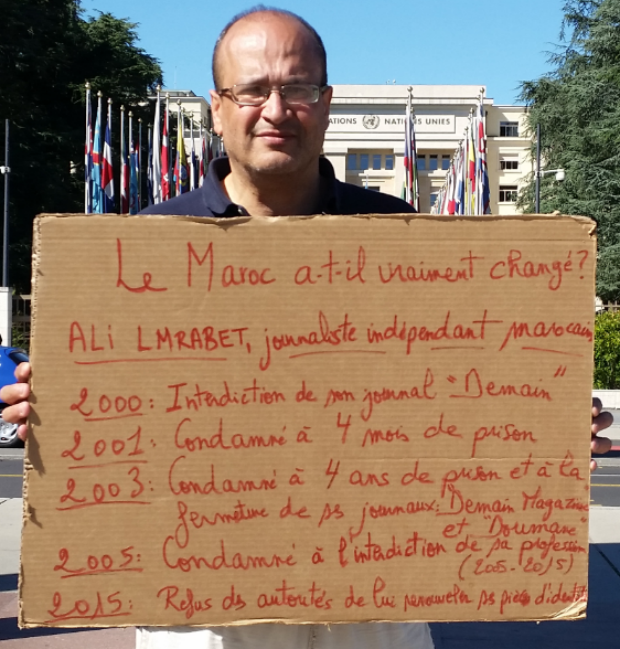

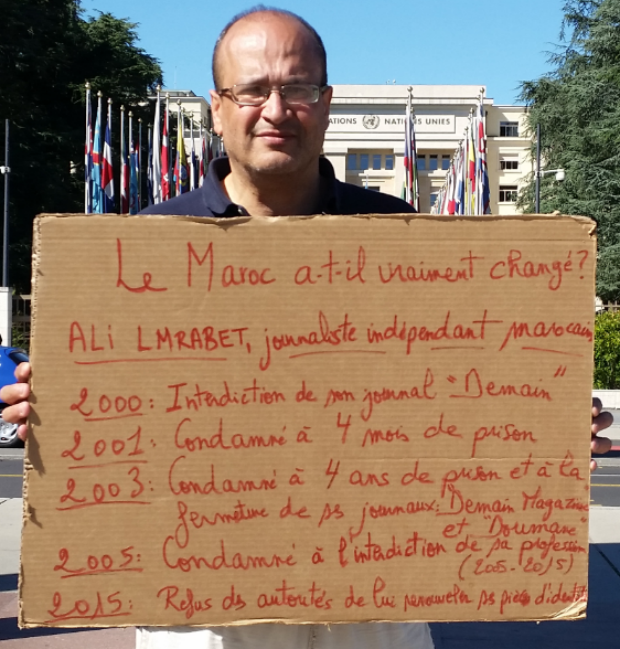

Ali Lmrabet was on hunger strike outside the UN building in Geneva (Photo: alisinpapeles.blogspot.com.es)

Moroccan officials said on Tuesday 28 July that satirist Ali Lmrabet’s passport would be renewed immediately. Lmrabet had been holding a hunger strike in front of the UN’s Geneva offices since 24 June because of refusals to renew his identity documents.

“The Moroccan authorities have publicly committed to renew his passport immediately, and not put obstacles to do the same with their identity. We hope that the authorities keep their word,” Lmrabet’s partner Laura Feliu wrote in an email to Index on Censorship.

Lmrabet called off his hunger strike and was admitted to hospital in Geneva for a checkup, according to Feliu.

In a period spanning over a decade, Lmrabet, who was the editor of two satirical publications, was continuously targeted by Moroccan authorities. In 2003, he was jailed for reporting on personal and financial affairs of Morocco’s King Mohammed VI. His magazine Demain was banned. Though initially handed down a three-year sentence, Lmrabet was released after six months. But his troubles were far from from over: in 2005, he was banned from practising journalism in his home country for ten years, over comments made about the dispute in Western Sahara between Morocco and the Algerian-backed Polisario Front.

As his ban expired in April this year, he returned to Morocco with the aim of relaunching Demain. But there he was denied a residency permit, without which he is unable to set up the magazine. In a further complication, he also needs the residence permit to renew his passport. When this expired on 24 June, Lmrabet, who was in Geneva to participate in a session of the UN Human Rights Council, decided to start a hunger strike.

Related:

• “He is denied his right to an identity”: why a Moroccan satirist is on hunger strike

• Open letter to the King of Morocco in support of Ali Lmrabet

This article was posted on 29 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org