17 Aug 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Back Row from left: Adam Rajab, Malak Rajab and Nabeel Rajab. Front Row from left: Sumaya Rajab and Zainab Alkhawaja. (Photo: Adam Rajab)

Human rights defenders often confront obstacles that make their work difficult. This is especially true in Bahrain, where the Sunni monarchy and government have been bent on silencing all opposition ever since the Arab Spring when tens of thousands of Bahraini citizens protested for democratic reform.

In recent months, the nation’s only independent news outlet, Al Wasat, was shuttered and prominent human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was sentenced to two years in prison for “spreading fake news”.

The families of activists suffer along with their loved ones and are often targeted with official harassment: detention, loss of employment, beatings and harassment. Each case is an individual story of a struggle for freedom.

A result of actions

Members of Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei’s family have been harassed and detained due to his ongoing campaigning for democracy and human rights in Bahrain. Most recently his mother-in-law and brother-in-law were detained while Alwadaei attended the United Nations Human Rights Council in March.

Alwadaei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, is no stranger to detention: he was arrested twice in 2011 and served a six-month sentence in a Bahraini jail. He found asylum in the UK in July 2012. In February 2015, Alwadaei was among 72 Bahraini citizens to be stripped of their citizenship.

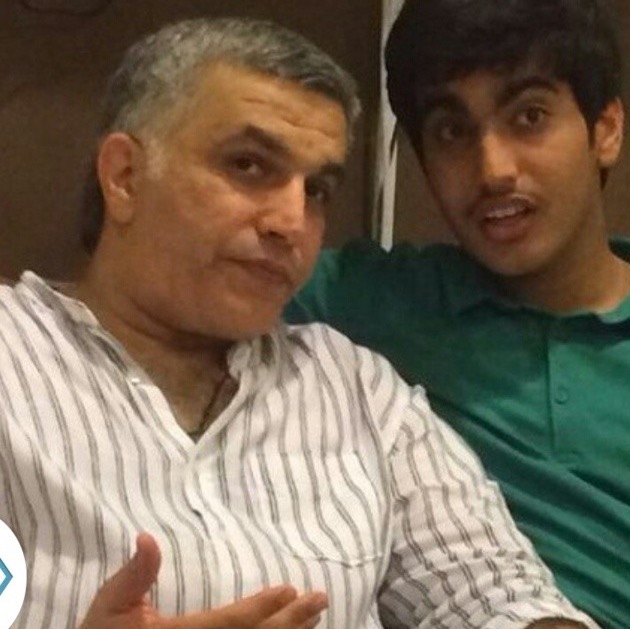

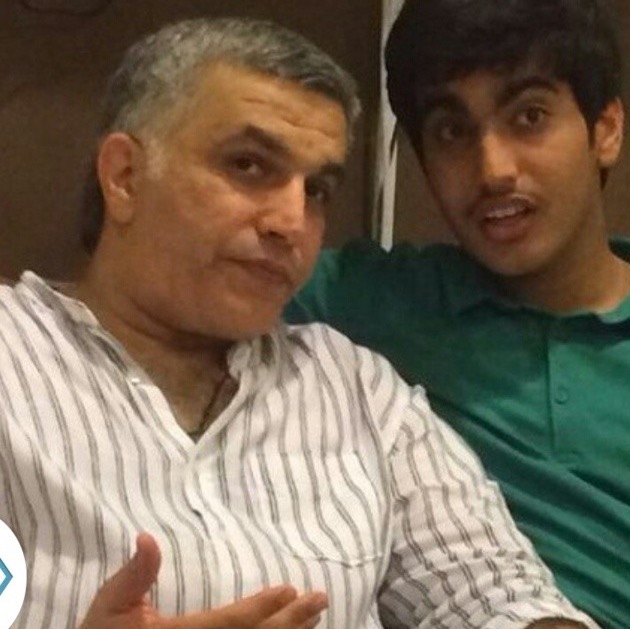

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei with his son Yousif (Photo: Moosa Satrawi)

In October 2016, Alwadaei’s wife and infant son Yousif also faced official harassment as they tried to leave Bahrain to join Alwadaei in the UK. His wife was arrested at the airport and held overnight, during which time she was ill-treated. It was not until a few months later that she and her son were able to leave the country.

Other members Alwadaei’s family, including his sister, have also faced interrogations.

When asked how he continues campaigning under these circumstances, Alwadaei told index: “We can only get through this by sticking together and staying strong. It’s important to have a supportive family. The potential for arrest and torture is something they know and have to be willing to sacrifice.”

He added that he is balancing his efforts to get his mother-in-law out of prison while continuing his work in activism. “It’s hard but this is the right thing to do.”

“The oppression or torture aims to do one thing: to break your will because you’re not ready for the consequences,” Alwadaei said. “This is the state they want to leave you in. They want you to be broken and this is why we keep going.”

A life-long struggle

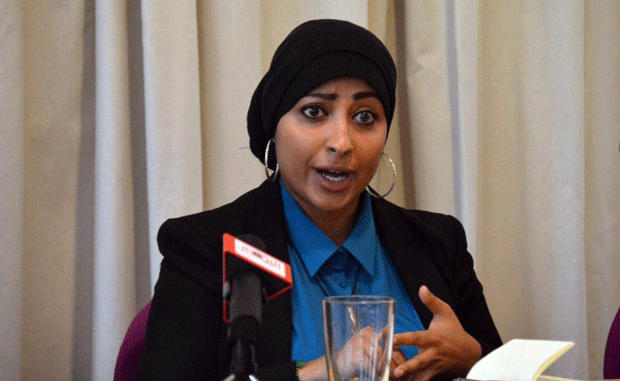

Maryam Al-Khawaja has been preparing for and participating in the struggle for human rights her entire life.

As a young child growing up in Denmark, she and her three sisters attended an English-speaking school, but the Al-Khawaja family knew they were only in the country temporarily. Her mother and father had been exiled for speaking out in Bahrain.

At a very young age, she remembers her parents asking her and her siblings before bed: “What have you done today to make the world a better place?” She told Index that her father wouldn’t help them answer the question because he wanted them to think about how the world could be. She remembers dinner conversations alive with politics and philosophical discussion about whether having false hope or no hope was better.

Around the 7th or 8th grade, Al-Khawaja knew wanted to be like her father when she grew up; she wanted to be an activist.

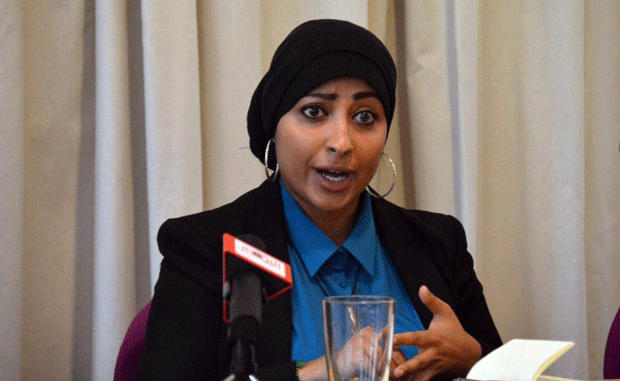

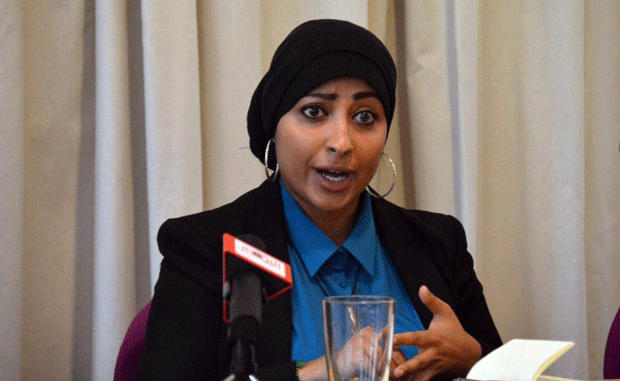

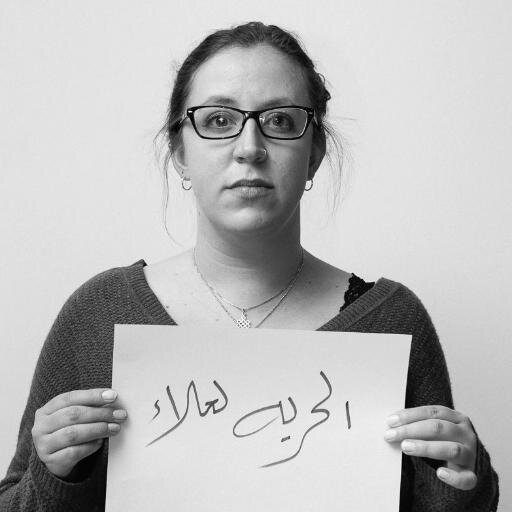

Maryam Al-Khawaja (Photo: David Coscia for Index on Censorship)

Al-Khawaja was 14 when her family returned to Bahrain in 2001. She recalls thinking her family was ready to take on the challenges and that the people of Bahrain would be ready to fight with them. But that was not the case. The country was tired of conflict and believed that the king’s promised reforms would be implemented. At the same time, activists were not popular among ordinary Bahrainis.

At college she said she was criticised by her classmates for speaking her mind about the state of their country, which caused her to lose interest in her father’s reform work. At the time, she asked him: “Why are you trying to change a situation for people who don’t want to change it for themselves?” His response was simple: “Someday you will understand.”

It wasn’t until 2011 during the Arab Spring protests that she developed a newfound respect for her father and was ashamed of herself for ever doubting him. She admits growing up in Denmark made her think fighting for human rights would be easy. When her father, along with 12 other leaders of the uprising, was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment, she found that a life of campaigning isn’t so effortless.

During our conversation, Al-Khawaja jumped off the phone for a few minutes to take a call from her father. She had not heard from him in over three weeks and said their phone calls are always random and typically short as it is normal for the line to be cut if anything about the Bahrain government or any activist’s work is mentioned.

Until recently, her mother and sisters in Bahrain had not seen her father since February as their requests to visit have continually been denied. Al-Khawaja has not seen her father since 2014 as there are multiple fabricated charges against her that would mean imprisonment if she returned to the country.

Since her father’s imprisonment, Al-Khawaja and her older sister Zainab have been active in the push for human rights and freedom of speech in Bahrain. She says her father has two main characteristics as an activist: a fierce advocate and a fiery speaker. She explained that she and Zainab are the two parts to that whole: Al-Khawaja as the advocate and Zainab as the speaker.

Al-Khawaja said the work of her father and her sister Zainab has been tough for her two younger sisters. One sister had the highest scores in nursing school in Bahrain and graduation seemed to promise a job. But the paperwork from the government granting her access to work never came. She’s been waiting nearly eight years without a job. Al-Khawaja said it’s difficult for her family members when they’re in jail as they have to “take care of us when we cannot take care of ourselves”.

Her mother also felt the effects of the family member’s work when she was fired from her private school teaching job where she was the head of guidance.

A cause for celebrity status never wanted

Adam Rajab realised when he was young that his father Nabeel wasn’t like other dads. “I was so confused ‘why does my father work all day, while other fathers have certain working hours?,’” he told Index.

During a holiday he asked his father to take a break for a day. His father answered: “My colleagues are in prison. I can’t stop my work because they are suffering behind bars.”

In 2006, when Rajab was nine years old, he vividly recalls seeing his father come home bleeding from his head with a swollen and bruised back. “I was shocked and terrified but my father continued protesting like nothing had happened,” he said. “This was terrifying to me but the determination and fearlessness I saw in him really inspired me.”

In 2011 Nabeel Rajab’s work became well known. He appeared on TV and was the first activist to use social media to support the revolution then sweeping Bahrain. “Wherever we went, people would stop him and start taking pictures,” Adam said, adding that the strange situation was a shock to the family. “It started to become difficult because we couldn’t enjoy a private life like we used to.”

Nabeel Rajab with his son Adam Rajab

As a leader of the movement, Rajab’s father has become a face leaders around the world recognise but do little about. For years he has been in and out of jail. On 10 July 2017 he was sentenced to two years in prison for “broadcasting fake news”.

Although no one in the family has been arrested, his mother was harassed at her government job and then fired. Rajab and his sister have also faced harassment in school.

Rajab and his father have a very close relationship so the imprisonment has not been easy. “I haven’t seen him for more than a year now and he faces more charges which probably means more prison sentences,” Rajab said. “I find it difficult to enjoy anything while he is locked up in a cell and deprived of life, but as he taught me, the spirit is always up.”

Rajab wants his father to free and for them to live like any other ordinary family, but this does not take away from how proud he is or the strength of his belief in his father’s cause.

An open ended sentence

It’s difficult to imagine the emotions these activists and their families go through on a daily basis. A psychologist from the Refer Self Counselling Psychology Practice explained to Index that having a family member with a sentence with a sure release date is one case but when trials or release dates are postponed time and time again as they are in Bahrain, it is much more difficult. “We are rational problem solvers but not good with the unpredictable.”

The psychologist explained the situation in Bahrain is unlike what most with family members behind bars will ever experience. False hope puts an even greater emotional strain on loved ones.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1503052292764-bb1a6c59-5e91-2″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Jan 2015 | Bahrain, mobile, News and features

Maryam Al-Khawaja spoke out in October for the release of fellow human rights activist Nabeel Rajab. (Photo: David Coscia for Index on Censorship)

Nine people have been arrested in Bahrain for “misusing social media”, a charge which is punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison.

Human rights defender Nabeel Rajab was last week sentenced to six months in prison over a tweet he posted which was deemed insulting to public institutions. Rajab has been bailed, and tweeted on 21 January that he will appeal his conviction on 11 February.

Human Rights Watch has dedicated seven pages of its 25th annual report to Bahrain. The World Report 2015, released on Thursday, reviews the human rights situation in over 90 countries.

The report states that over 200 defendants have been sentenced to long stints in prison by the Bahraini courts on charges of national security or terrorism, with at least 70 of those being sentenced to life.

It says: “Bahrain’s courts convicted and imprisoned peaceful dissenters and failed to hold officials accountable for torture and other serious rights violations. The high rate of successful prosecutions on vague terrorism charges, imposition of long prison sentences, and failure to address the security forces’ use of lethal and apparently disproportionate force all reflected the weakness of the justice system and its lack of independence.”

In December, co-director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR), Maryam Al-Khawaja, boycotted a court hearing which saw her sentenced to one year in prison. Al-Khawaja was charged with assaulting two policewomen last year when she traveled to Bahrain to visit her father Abdulhadi, who is currently serving a life sentence for his involvement in anti-government protests in 2011. In related news, the GCHR website was yesterday reportedly blocked in the United Arab Emirates.

Al-Khawaja’s sister Zainab was arrested in October on charges of insulting the king, and gave birth to her second child just a few days before being sentenced to three years in prison. She was then sentenced to an additional 16 months less than a week later, on separate charges of insulting a public official.

This article was published on 30 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

1 Sep 2014 | Bahrain, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

UPDATE 4 September 17:22: Maryam Alkhawaja has a court date scheduled for 9am on Saturday 6 September, according to Travis Brimhall, head of the international office at the Bahrain Center for Human Rights.

Prominent human rights activist Maryam Alkhawaja has been jailed in Bahrain. She was detained at Bahrain International Airport on Friday as she tried to enter the country, and has yet to meet with her lawyer.

Alkhawaja, a dual Danish-Bahraini citizen, had her Danish passport confiscated and was told she no longer held Bahraini citizenship. She was also barred from using her phone or contacting her family, according to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), the organisation of which she is co-director. GCHR also reported that she was interrogated on charges of assaulting and injuring police officers, while lawyer Mohamed Al Jishi said he was not allowed to speak to his client before she was questioned. She is currently held in Isa Town women’s prison.

Alkhawaja was travelling to see her imprisoned father, who last week started a hunger strike. Abdulhadi Alkhawaja is a Bahraini human rights campaigner who co-founded the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR), which won the 2012 Index Freedom of Expression Award for Advocacy. He was sentenced to life in prison on terrorism charges following pro-democracy protests that swept the country in 2011. Abdulhadi and his daughters Maryam and Zainab are outspoken critics of human rights violations in the constitutional monarchy, which is categorised as “not free” by Freedom House.

The case first gained attention after Alkhawaja tweeted about being detained on Friday, and an unnamed person close to the family continues to provide updates through her Twitter account. On Saturday, the account reported that she is also facing charges of insulting the king of Bahrain and over an anti-impunity campaign she was involved with in November 2013.

Human Rights Watch called the arrest “outrageous”, while GCHR has labelled the charges “fabricated” and has called on the international community to put pressure on Bahraini authorities to release father and daughter. The Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs is sending a representative to Bahrain to provide support. Foreign Minister Martin Lidegaard tweeted on Sunday that a “solution must be found in Al-Khawaja case” and that he has raised the issue with the European Union.

This comes as the Supreme Court of Appeal in Bahrain on Sunday upheld a 10-year sentence on photographer Ahmad Humaidan. He was convicted over an attack on a police station in 2012, but human rights groups believe the case against him is connected to his coverage of pro-democracy demonstrations.

This article was posted on 1 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

8 Mar 2014 | Azerbaijan News, News and features

International Women’s Day is a day to remember violence against women, the education gap, the wage gap, online harassment, everyday sexism, the intersection between sexism and other -isms, and a whole host of other issues to make us realise we’ve still got a long way to go. A day to demand continued progress, and a day to pledge to work to achieve it.

But it is also a day to celebrate. To appreciate the fantastic achievements that are made every day, everywhere, by women from all walks of life. It’s a day to be grateful to the women who dedicate their lives to fighting on the front lines to protect rights vital to us all. We want to shine the spotlight on women who have stood up for freedom of expression when it’s not the easy or popular thing to do, against fierce opposition and often at great personal risk. The following eight women have done just that. We know there are many, many more. Tell us about your female free speech hero in the comments or tweet us @IndexCensorship.

Meltem Arikan — Turkey

Meltem Arikan

Arikan is a writer who has long used her work to challenge patriarchal structures in society. He latest play “Mi Minor” was staged in Istanbul from December 2012 to April 2013, and told the story of a pianist who used social media to challenge the regime. Only a few months after, the Gezi Park protests broke out in Turkey. What started as an environmental demonstration quickly turned into a platform for the public to express their general dissatisfaction with the authorities — and social media played a huge role. Arikan was one of many to join in the Gezi Park movement, and has written a powerful personal account of her experiences. But a prominent name in Turkey, she was accused of being an organiser behind the protests, and faced a torrent of online abuse from government supporters. She was forced to flee, now living in exile in the UK.

I realised that we were surrounded, imprisoned in our own home and prevented from expressing ourselves freely.

Anabel Hernández — Mexico

Anabel Hernández (Image: YouTube)

Hernández is a Mexican journalist known for her investigative reporting on the links between the country’s notorious drug cartels, government officials and the police. Following the publication of her book Los Señores del Narco (Narcoland), she received so many death threats that she was assigned round-the-clock protection. She can tell of opening the door to her home only to find a decapitated animal in front of her. Before Christmas, armed men arrived in her neighbourhood, disabled the security cameras and went to several houses looking for her. She was not at home, but one of her bodyguards was attacked and it was made clear that the visit — from people first identifying themselves as members of the police, then as Zetas — was because of her writing.

Many of these murders of my colleagues have been hidden away, surrounded by silence – they received a threat, and told no one; no one knew what was happening…We have to make these threats public. We have to challenge the authorities to protect our press by making every threat public – so they have no excuse.

Amira Osman — Sudan

Amira Osman (Image: YouTube)

Amira Osman, a Sudanese engineer and women’s rights activist was last year arrested under the country’s draconian public order act, for refusing to pull up her headscarf. She was tried for “indecent conduct” under Article 152 of the Sudanese penal code, an offence potentially punishable by flogging. Osman used her case raise awareness around the problems of the public order law. She recorded a powerful video, calling on people to join her at the courthouse, and “put the Public Order Law on trial”. Her legal team has challenged the constitutionality of the law, and the trial as been postponed for the time being.

This case is not my own, it is a cause of all the Sudanese people who are being humiliated in their country, and their sisters, mothers, daughters, and colleagues are being flogged.

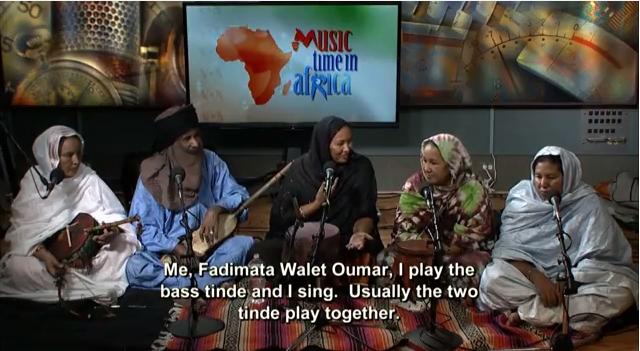

Fadiamata Walet Oumar — Mali

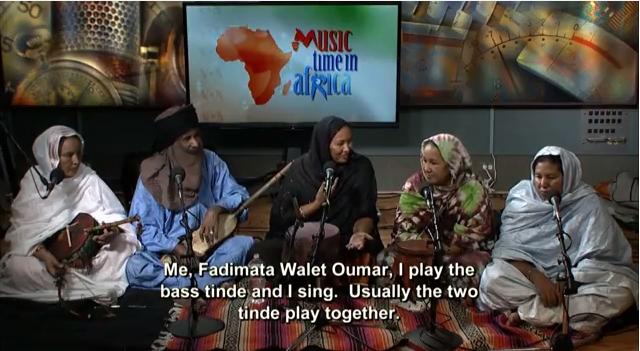

Fadiamata Walet Oumar with her band Tartit (Image: YouTube)

Fadiamata Walet Oumar is a Tuareg musician from Mali. She is the lead singer and founder of Tartit, the most famous band in the world performing traditional Tuareg music. The group work to preserve a culture threatened by the conflict and instability in northern Mali. Ansar Dine, an islamists rebel group, has imposed one of the most extreme interpretations of sharia law in the areas they control, including a music ban. Oumar believes this is because news and information is being disseminated through music. She fled to a refugee camp in Burkina Faso, where she has continued performing — taking care to hide her identity, so family in Mali would not be targeted over it. She also works with an organisation promoting women’s rights.

Music plays an important role in the life of Tuareg women. Our music gives women liberty…Freedom of expression is the most important thing in the world, and music is a part of freedom. If we don’t have freedom of expression, how can you genuinely have music?

Khadija Ismayilova — Azerbaijan

Khadija Ismayilova

Ismayilova is an award-winning Azerbaijani journalist, working with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. She is know for her investigative reporting on corruption connected to the country’s president Ilham Aliyev. Azerbaijan has a notoriously poor record on human rights, including press freedom, and Ismayilova has been repeatedly targeted over her work. She was blackmailed with images of an intimate nature of her and her boyfriend, with the message to stop “behaving improperly”. This February, she was taken in for questioning by the general prosecutor several times, accused of handing over state secrets because she had met with visitors from the US Senate. In light of this, she posted a powerful message on her Facebook profile, pleading for international support in the event of he arrest.

WHEN MY CASE IS CONCERNED, if you can, please support by standing for freedom of speech and freedom of privacy in this country as loudly as possible. Otherwise, I rather prefer you not to act at all.

Jillian York — US

Jillian York (Image: Jillian C. York/Twitter)

Jillian York is a writer and activist, and Director of Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). She is a passionate advocate of freedom of expression in the digital age, and has spoken and written extensively on the topic. She is also a fierce critic of the mass surveillance undertaken by the NSA and other governments and government agencies. The EFF was one of the early organisers of The Day We Fight Back, a recent world-wide online campaign calling for new laws to curtail mass surveillance.

Dissent is an essential element to a free society and mass surveillance without due process — whether undertaken by the government of Bahrain, Russia, the US, or anywhere in between — threatens to stifle and smother that dissent, leaving in its wake a populace cowed by fear.

Cao Shunli — China

Cao Shunli (Image: Pablo M. Díez/Twitter)

Shunli is an human rights activist who has long campaigned for the right to increased citizens input into China’s Universal Periodic Review — the UN review of a country’s human rights record — and other human rights reports. Among other things, she took part in a two-month sit-in outside the Foreign Ministry. She has been targeted by authorities on a number of occasions over her activism, including being sent to a labour camp on at least two occasions. In September, she went missing after authorities stopped her from attending a human rights conference in Geneva. Only in October was she formally arrested, and charged for “picking quarrels and promoting troubles”. She has been detained ever since. The latest news is that she is seriously ill, and being denied medical treatment.

The SHRAP [State Human Rights Action Plan, released in 2012] hasn’t reached the UN standard to include vulnerable groups. The SHRAP also has avoided sensitive issue of human rights in China. It is actually to support the suppression of petitions, and to encourage corruption.

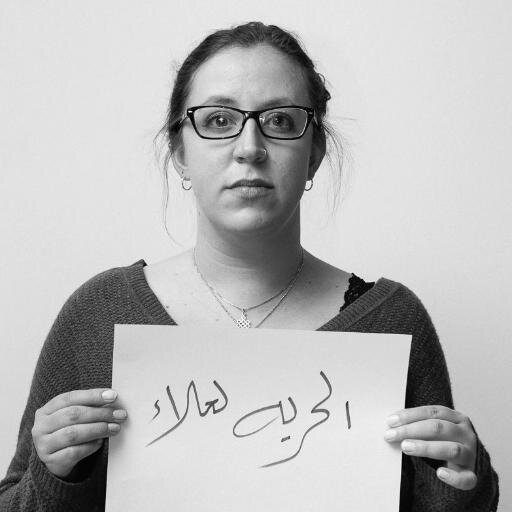

Zainab Al Khawaja — Bahrain

Zainab Al Khawaja

Al Khawaja is a Bahraini human rights activist, who is one of the leading figures in the Gulf kingdom’s ongoing pro-democracy movement. She has brought international attention to human rights abuses and repression by the ruling royal family, among other things, through her Twitter account. She has also taken part in a number of protests, once being shot at close range with tear gas. Al Khawaja has been detained several times over the last few years, over “crimes” like allegedly tearing up a photo of King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. She had been in jail for nearly a year when she was released in February, but she still faces trials over charges like “insulting a police officer”. She is the daughter of prominent human rights defender Abdulhadi Al Khawaja, who is currently serving a life sentence.

Being a political prisoner in Bahrain, I try to find a way to fight from within the fortress of the enemy, as Mandela describes it. Not long after I was placed in a cell with fourteen people—two of whom are convicted murderers—I was handed the orange prison uniform. I knew I could not wear the uniform without having to swallow a little of my dignity. Refusing to wear the convicts’ clothes because I have not committed a crime, that was my small version of civil disobedience.

This article was posted on March 8, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org