1 Sep 2017 | Index in the Press

A recently censored image of a nipple has highlighted a well-known fact, namely that a male nipple is just a nipple, but a woman’s nipple is deviant. Stare directly at them and you shall turn to stone. Read the full article

8 Aug 2017 | Artistic Freedom, Magazine, News and features, Russia, Volume 46.02 Summer 2017

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Influential Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein is often portrayed as the godfather of propaganda in film. David Aaronovitch argues in the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine that historical drama can also be manipulative when it ignores details of the past”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

A still from Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 film, Battleship Potemkin, portraying a massacre that never happened. Credit: Wikimedia

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

My friend, a writer, reminded me of the English romantic poet John Keats’s axiom that “we hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us”. You could say, though, that Lenin and Mussolini – at least when it came to the poetry of film – knew differently. “Of all the arts, for us,” said Lenin, “the cinema is the most important”. “For us” meaning, of course, for the ruling Bolsheviks in the aftermath of the October 1917 revolution. When the Italian dictator Mussolini’s new super studios were opened in 1936 a sign was erected over the gate reading “Il cinema è l’arma più forte”, “cinema is the strongest weapon”.

It was George Orwell, not a dictator (though they doubtless would smilingly have agreed with him) who wrote that, “he who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past.” It is pretty obvious that the way the powerful medium of film depicts the “then” has important implications for what people can be brought to believe about the “now”.

I was brought up partly on films made in the Soviet Union and saw some of the most celebrated early movies when I was young. The director Sergei Eisenstein was the most famous name and before I was 12 I’d seen almost all his films, from the silent Strike made in 1924 to the extraordinarily ambivalent and terrifying two-part classic Ivan the Terrible. Every single one of them can be said to have had some kind of agenda that dovetailed – sometimes perfectly, sometimes awkwardly – with that of the Soviet state.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The massacre on the Odessa steps (once seen, never forgotten) from the movie Potemkin didn’t actually happen” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

The two that were most obviously about Bolshevism and Russia were The Battleship Potemkin, dealing with events in the city of Odessa in 1905, and October, an account of the “ten days that shook the world” – the Bolshevik seizure of power – in Petrograd (St Petersburg) in 1917.

Both deploy Eisenstein’s famous techniques of intercutting, juxtaposition and montage to create mood and drama. Sometimes cutaways of objects or expressions are inserted to refer obliquely to what the viewer is supposed to think of the person or the moment being depicted.

And in both films the actual history is bent for the purposes of the filmmaker. The massacre on the Odessa steps (once seen, never forgotten) from the movie Potemkin didn’t actually happen. The film version of the storming of the Winter Palace in October involved many more actors than the actual event itself. And October was criticised in Keatsian terms by no less a luminary than Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya.

The full article by David Aaronovitch is available with a print or online subscription.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Film and the Soviet state”][vc_column_text]

Sidebar by Margaret Flynn Sapia

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3UQMg3saU4Q&t=1s” title=”Strike (1925)”][vc_column_text]The Soviet version of Russian history had two goals: to legitimise the rise and rule of the current government, and to instil its values into future generations. Strike, the first film directed by Sergei Eisenstein, undoubtedly does both. The film, set before the revolution, tells the story of a group of factory workers as they rise up against their abusive management. It begins with a quote by Lenin – “The strength of the working class is organisation” – and ends with a violent strike cross cut with the slaughter of animals. From the first frame to the last, the message is clear.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JcJkHCihTmE” title=”Ivan the Terrible (1944)”][vc_column_text]It is fitting that Joseph Stalin regarded Tsar Ivan IV as his role model, given that the two men men are renowned as two of Russia’s cruelest and most feared leaders. Directed by Eisenstein and commissioned by Stalin himself, Ivan the Terrible takes a stab at telling Ivan’s story in a way that flatters the Stalin regime. The plot portrays the boyars, the highest of bourgeois aristocracy, as internal enemies seeking to undermine the singular strength of Ivan’s leadership, a less-than-subtle parallel for the one-party Soviet state of the 1940’s.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kS5kzTbNKjs” title=”Battleship Potemkin (1925)”][vc_column_text]Like a dozen other Soviet films, The Battleship Potemkin depicts the horrors of the tsarist regime and a subsequent popular revolt. It dramatises the true story of a 1905 mutiny by the crew on a Russian battleship, but its most famous and enduring scene, the massacre on the Odessa steps, was entirely invented. However, unlike many of its comrades, this movie was internationally celebrated for its technical excellence, and was ranked as the 11th best film of all time in a 2017 BFI critics poll. Through the film’s five acts, Eisenstein demonstrates that propaganda and art are not mutually exclusive, and that the confines of oppression can sometimes breed incredible creativity.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=riOLSslKvxU” title=”October: 10 Days That Shook the World (1928)”][vc_column_text]A retelling of Russia’s 1917 Revolution, this film creates a fascinatingly skewed representation of the Soviet Union’s rise. While the series of major events in the film is historically accurate, the depictions of Soviet leaders and opposition give the film’s biases away, as key facets of character and decisions are highlighted and hidden. When watching the film, pay special attention to the portrayals of Lenin and the Bolsheviks. [/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-QBqT9RQAM” title=”Panfilov’s 28 Men (2016)”][vc_column_text]Panfilov’s 28 Men demonstrates how Russian manipulation of history did not end with the Soviet Union. Released in 2016, this film is based on a famous but disputed incident in World War II wherein a small group of Russian soldiers purportedly warded off a wave of Nazi tanks and soldiers, all dying in the process. The events were heavily embellished by Soviet propagandists and later debunked, but the film based on them was partially funded by the Russian Ministry of Culture and is widely advertised as an accurate depiction of historical events. Times change, but the Russian regime continues to use cinema to its benefit.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This article is published in full in the Summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Print copies of the magazine are available on Amazon, or you can find information about print or digital subscriptions here. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), and Home (Manchester). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80560″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422014523227″][vc_custom_heading text=”Reel Drama: WWII propaganda” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422014523227|||”][vc_column_text]March 2014

David Aaronovitch argues that all’s fair in war against fascist dictatorship, including seducing the United States into war with pretty faces and British accents.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89184″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220512331339706″][vc_custom_heading text=”The ferghana canal” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064220512331339706|||”][vc_column_text]February 2005

The first 145 shots of a shooting-script by Sergei Eistenstein, a prologue to the modern drama of Uzbekistan’s reclamation of its desert wastes.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”98486″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229108535073″][vc_custom_heading text=”Iron fist, silver screen” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229108535073|||”][vc_column_text]March 1991

An examination of how film is an arm of party propaganda in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, highlighting the 1973 Law on Censorship of Foreign Films.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”100 Years On” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F06%2F100-years-on%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the consequences of the 1917 Russian Revolution still affect freedoms today, in Russia and around the world.

With: Andrei Arkhangelsky, BG Muhn, Nina Khrushcheva[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/06/100-years-on/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

31 Jul 2017 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/EbGIEmUhbLQ”][vc_column_text]Centre for Turkey Studies (CEFTUS), a London-based non-profit organisation that organises monthly events in London dedicated to Turkey, will be holding the sixth Annual Turkish, Kurdish and Turkish Cypriot Community Achievement Awards at the CEFTUS Anniversary Gala on 8 October. Index on Censorship is proud to be a partner in supporting this event.

CEFTUS is seeking nominations for the awards. If you know a Turk, Kurd or Turkish Cypriot who deserves recognition for their hard work in the community then we invite you to nominate them for an award. You can do this by filling out a nomination form with the name, contact details and a reason why you think your nominee qualifies them for an award. To fill out the form, please follow this link.

The categories are listed below:

Female /Male Role Model

Politics and Education

Law Firm/Lawyers

Community Organisations/Charity

Businessman of the year

Businesswoman of the year

Food and restaurants

Financial Services/Accountancy

Wholesalers/Production/best Employer

Young Entrepreneurs

More information about the CEFTUS Anniversary Gala can be found here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Sunday 8 October 2017 18:00-23:00

Where: Westminster Park Plaza Hotel, 200 Westminister Bridge Rd, Lambeth, London SE1 7UT

Tickets: Via CEFTUS

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Jul 2017 | Artistic Freedom, News and features, Volume 46.02 Summer 2017 Extras, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Members of Index’s youth board looked at three famous works that fell victim to the Russian censors”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the long-term consequences of 1917 Russian Revolution, which launched the global communist experiment, and the long-term impact that it had on free speech around the world. Here, three members of Index’s youth board give examples of works that failed to find favour with the authorities the revolution ushered in.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The original Italian edition of Dr Zhivago. Credit: Wikimedia

Dr Zhivago – Boris Pasternak

Isabela Vrba Neves (Stockholm)

A depiction of Russian life between the Bolshevik Revolution and World War II, Dr Zhivago (1957) by Boris Pasternak is a piece of literature presenting the reader with romance and the tragedies experienced by Russians during the early twentieth century.

Dr Zhivago tells the story of Yuri Zhivago, a man suffering hardship throughout his life, from becoming an orphan to being in love with two women and arousing the suspicions of those in power. Through an intricate plot introducing many characters, Zhivago witnesses the revolution and civil war, all while exploring questions of religion and philosophy.

Pasternak submitted his book for publishing in 1956 but was rejected in the Soviet Union due to it containing anti-Soviet passages and criticism of the Bolsheviks. As a result, the book was banned in the Soviet Union until 1988. However, in 1957 a manuscript was smuggled to Milan, where it was first published.

The following year Pasternak was awarded a Nobel Prize in Literature, which he had to turn down after being threatened with ejection from the Soviet Union. The award was later accepted in 1988 by his relatives.

A film adaptation of Dr Zhivago was released in 1965, starring the late actor Omar Sharif and Geraldine Chaplin. Immensely popular in Europe and North America, the film adaption was also banned for many years in the Soviet Union.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The cover of Stefan Zweig’s Beware of Pity. Credit: Wikimedia

The Collected Novellas of Stefan Zweig

Samuel Rowe (London)

As I was leaving a house on the outskirts of Copenhagen some summers ago, I was handed a bright orange hardback book. It was The Collected Novellas of Stefan Zweig. I was told that Zweig’s novel, Beware of Pity, had loosely inspired the 2014 Wes Anderson film The Grand Budapest Hotel and that Zweig’s works had been burned in the streets during the Third Reich. But this was not the first time his literature had been burned.

Not long before – 30 October 1929, to be precise – Krupskaia Lenin, wife of Vladmir, had sent out a circular to all librarians in the Soviet Union. It contained a list of literature considered decadent or which fostered “social pessimism”, and required they be removed from all public libraries. Zweig’s stories could have fallen into the former or the latter category; his stories were popular and hilarious, subversive and frank.

Once the procedure was completed, two copies of each title on the list were sent to the central library of each region, accessible only to qualified researchers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

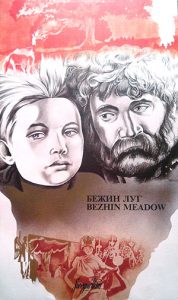

A poster for Bezhin Meadow. Credit: Wikimedia

Bezhin Meadow – Sergei Eisenstein

Sophia Smith-Galer (London)

One of the most famous films to have been scuppered by censorship in the Soviet Union was Bezhin Meadow, a film adaptation of the story Bezhin lug by Ivan Turgenev. The film, directed by Sergei Eisenstein, was believed to have been destroyed before its completion, but parts of it resurfaced in the 1960’s, allowing for a crude recreation.

The main character Ivan’s life story was based on the life of Pavlik Morozov, a young Russian boy who denounced his father to the Soviet Union and, ultimately, died at the hands of his family. It grew to become a story of political martyrdom after his death in 1932.

Sergei Eisenstein was nonetheless already a world famous film director – Battleship Potemkin (1925) is still used as an example of groundbreaking cinematography to this day – and is best remembered for pioneering the montage.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This piece was written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board. You can find out more about the youth advisory board here

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”100 Years On” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F06%2F100-years-on%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the consequences of the 1917 Russian Revolution still affect freedoms today, in Russia and around the world.

With: Andrei Arkhangelsky, BG Muhn, Nina Khrushcheva[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/magazine”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]