22 Sep 2015 | Austria, mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Panelists at the OSCE meet on online attacks against journalists: writer Arzu Geybulla; Gavin Rees, Europe director of the Dart Center for journalism and trauma; Becky Gardiner, from Goldsmiths, University of London; journalist Caroline Criado Perez

“This is not something that only ‘ladies’ can fix,” emphasised Dunja Mijatovic, the OSCE’s Representative on Freedom of the Media at an expert meeting on the safety of female journalists in Vienna on 17 September 2015, which Index on Censorship attended.

The importance of collectively tackling the growing problem became an overarching theme of the conference. “There is a new and alarming trend for women journalists and bloggers to be singled out for online harassment,” said Mijatovic, while highlighting the importance of media, state and NGO voices coming together to address the abuse.

Arzu Geybulla and Caroline Criado Perez, journalists from Azerbaijan and the UK respectively, started the meeting with moving testaments of their own experiences. Despite covering very different topics, they have received shockingly similar threats – sexual, violent and personal. “Shut your mouth or I’ll shut it for you and choke you with my dick” was one of the messages received by Perez after she campaigned for a woman to feature on British banknotes.

Although male journalists also receive abuse, women experience a two-fold attack, including the gendered threats. Think tank Demos has estimated that female journalists experience roughly three times as many abusive comments as their male counterparts on Twitter.

The problem, said Perez, was not just the threats but how the women who receive them are then treated. “Women are accused of being mad or attention seeking, which are all ways of delegitimising women’s speech,” she said. “People told me to stop, close my Twitter account, go offline. But why is the solution to shut up?” She added: “This is a societal problem, not an internet problem.”

“Labelling a person, and making that person an object, is particularly common in Azerbaijan,” said Geybulla, an Azeri journalist and Index on Censorship magazine contributor who was labelled a traitor and viciously targeted online after writing for a Turkish-Armenian newspaper. “Our society is not ready to speak out. You can’t go to the police. The police think it must be your fault.”

The intention of the meeting was to highlight the problem, while also proposing courses of actions. Suggestions included calls for more education in digital literacy; more training for police; more support from editors and media organisations, and from male colleagues. There was some disagreement on whether the laws were robust enough as they stand, or needed an update for the internet age.

Becky Gardiner, formerly editor of Guardian’s Comment is Free section, spoke about how her own views on dealing with online abuse had changed, having initially told writers they should develop a thicker skin. “It is not enough to tell people to get tough. Disarming the comments is not a solution either. That genie is out of the bottle.” Gardiner, who is now a lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, is working on research into the issue, as commissioned by the Guardian’s new editor, Kath Viner.

It was suggested that small but crucial steps could be taken by media organisations to avoid inflammatory and misleading headlines (which are not written by the journalist, but put them in the firing line) and to be careful of exposing inexperienced writers without preparation or support. Sarah Jeong from Vice’s Motherboard plaform said, in her experience, freelancers often came the most under attack because they don’t have institutional backing.

The OSCE said this will be the first in a series of meetings, with the aim of getting more organisations to take it serious and to produce more concrete courses of action.

Read more about the online abuse of women in the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, with a personal account by Gamergate target Brianna Wu and a legal overview by Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (Fire).

Tweets from OSCE’s #FemJournoSafe conference:

https://twitter.com/julieposetti/status/644456066432937984

18 Sep 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Shirin Abbasov (Photo: Meydan.tv)

The Sport for Rights Coalition condemns the Azerbaijani authorities’ extensive pressure against the staff of independent online television station Meydan TV, as part of a wider unprecedented crackdown on free expression and independent media. Following months of increased pressure in the aftermath of the European Games and the run-up to the 1 November parliamentary elections, on 17 September, Meydan TV reporter Shirin Abbasov was sentenced to 30 days of administrative detention for “disobeying police”. On 18 September, authorities searched the flat of another Meydan TV reporter, Javid Abdullayev, in connection with the case against Abbasov, seizing computers and cameras – indicating more serious charges might be forthcoming.

Abbasov, a 19 year-old freelance journalist and Meydan TV contributor, went missing on his way to university early the afternoon of 16 September, and his whereabouts were unknown for nearly 30 hours. Authorities eventually disclosed that Abbasov was being held at the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ notorious Department to Combat Organised Crime. Abbasov has so far been prevented from seeing his lawyer, who fears that Abbasov may be under pressure to sign a false confession.

“The arrest of Shirin Abbasov is yet another act by the authorities aimed at silencing independent voices in Azerbaijan”, said IMS Executive Director Jesper Højberg. “Locking up government critics and stepping up pressure on the country’s few remaining independent media outlets and NGOs has had disastrous consequences for Azerbaijan’s international relations, and certainly does not bode well for the upcoming parliamentary elections. The Azerbaijani government must take action now to put a stop to this downward spiral”.

Prior to his arrest, Abbasov was one of four Meydan TV staff prevented from leaving Azerbaijan after the conclusion of the European Games in June, told they were placed on a “blacklist” for unclear reasons. More recently, he covered the trials of human rights defenders Leyla and Arif Yunus, and journalist Khadija Ismayilova, capturing some of the only images of the political prisoners that were used in the press. Abbasov is also a popular video blogger, whose Facebook posts critical of the government have drawn widespread attention. He was one of six Meydan TV staff previously questioned over Meydan TV’s coverage of protests in the city of Mingechevir calling for the resignation of the local police chief following the 20 August death of a man in policy custody.

Also on 16 September, another young freelance journalist and Meydan TV contributor, Aytaj Ahmadova, was detained along with a friend and questioned for five hours by employees of the same Department to Combat Organised Crime, before being released. She reported that similarly to her colleagues, questions were focused on the Mingechevir protests, as well as Meydan TV’s activities, and its management and salary structure. Ahmadova’s parents have reportedly been fired from their jobs and threatened with arrest.

“The extensive questioning of Meydan TV’s staff in connection with the Mingechevir protests bears similar hallmarks to the cases built against journalist Tofig Yagublu and opposition leader Ilgar Mammadov – both of whom remain imprisoned on spurious charges connected with the 2013 protests in Ismayilli”, stated Thomas Hughes, ARTICLE 19’s Executive Director. “The Azerbaijani government should immediately cease its persecution of journalists working with Meydan TV, as well as any others legitimately expressing critical or independent viewpoints. Azerbaijan’s current actions, following a year of persistent crackdown down on freedom of expression, are in direct violation of its international obligations”.

In June, Meydan TV Director Emin Milli reported that he had received a threat from the Azerbaijani Minister of Youth and Sport, Azad Rahimov, in connection with Meydan TV’s critical reporting on the European Games. In July, 23 of his relatives signed a letter to Azerbaijani President Aliyev stating that they did not support Milli’s “anti-Azerbaijani policy” and had excluded him from the family for his “betrayal of Azerbaijan”. Meydan TV editor and popular writer Gunel Movlud also reported that her relatives have faced pressure in connection with her work; so far at least four have been fired from their jobs.

The growing pressure against the staff of Meydan TV takes place against a broader unprecedented crackdown on free expression and the independent media. In addition to Abbasov, there are eight journalists behind bars in Azerbaijan, as well as six human rights defenders who are strong free expression advocates, along with dozens of other political prisoners, many of whom were targeted for expressing critical opinions.

For more than a year, the staff of media freedom NGO the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS) – where detained journalist Shirin Abbasov worked prior to Meydan TV – has faced tremendous pressure, culminating with the murder of IRFS Chairman Rasim Aliyev, who died in hospital on 9 August after being severely beaten the day before. The attack on Aliyev took place one year from the date authorities had raided and closed the office of IRFS and its online TV project, Obyektiv TV, which were forced to cease operations.

That same day, 8 August 2014, IRFS Director Emin Huseynov was forced into hiding, and was soon after granted refuge at the Swiss Embassy in Baku, where he remained for 10 months until he was finally allowed out of the country, but stripped of his Azerbaijani citizenship. Huseynov remains in exile abroad as a stateless person. His brother Mehman Huseynov, a well-known photojournalist and blogger, was detained earlier this month when he tried to obtain a replacement ID card as authorities had seized his in connection with a politically motivated criminal case against him from 2012. He has been prevented from leaving the country since June 2013. In January this year, IRFS deputy head Gunay Ismayilova was attacked outside her apartment in Baku.

Other independent media that have been facing extensive pressure include Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL)’s Baku bureau, which was raided and closed by authorities in December 2014, shortly after the arrest of its former bureau chief and prominent investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova, who was sentenced on 1 September to 7.5 years in prison on spurious charges. Opposition Azadliq newspaper once again teeters on the brink of closure after years of excessive fines from defamation cases filed by public officials and their supporters, and other financial pressures. ‘Azerbaycan saati’ (Azerbaijan Hour), an opposition-minded online television station, has also faced extensive pressure, including the arrest of its presenter Seymur Hezi, who is currently serving a five-year prison sentence on spurious charges.

The Sport for Rights coalition condemns these acts aimed at silencing independent voices in Azerbaijan and punishing those who were critical in the run-up to the European Games. Sport for Rights believes that the pressure against Meydan TV is directly connected to its critical coverage of the European Games. Sport for Rights also notes that Meydan TV and the other organisations and individuals being targeted have all played an important role in exposing corruption and human rights abuses — which has become downright dangerous in Azerbaijan.

Sport for Rights calls for the immediate and unconditional release of Shirin Abbasov, as well as the other jailed journalists and human rights defenders in Azerbaijan. Sport for Rights also calls for the Azerbaijani authorities to put a stop to all acts of persecution of Meydan TV’s staff and other journalists and human rights defenders, and to take urgent steps to address the broader human rights crisis in the country ahead of the 1 November parliamentary elections.

Supporting organisations:

ARTICLE 19

Civil Rights Defenders

Committee to Protect Journalists

Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF)

Index on Censorship

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), in the framework of the

Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

International Media Support (IMS)

International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR)

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN American Center

People in Need

Platform

Polish Green Network

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), in the framework of the

Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

YouAid Foundation

[smartslider2 slider=”35″]

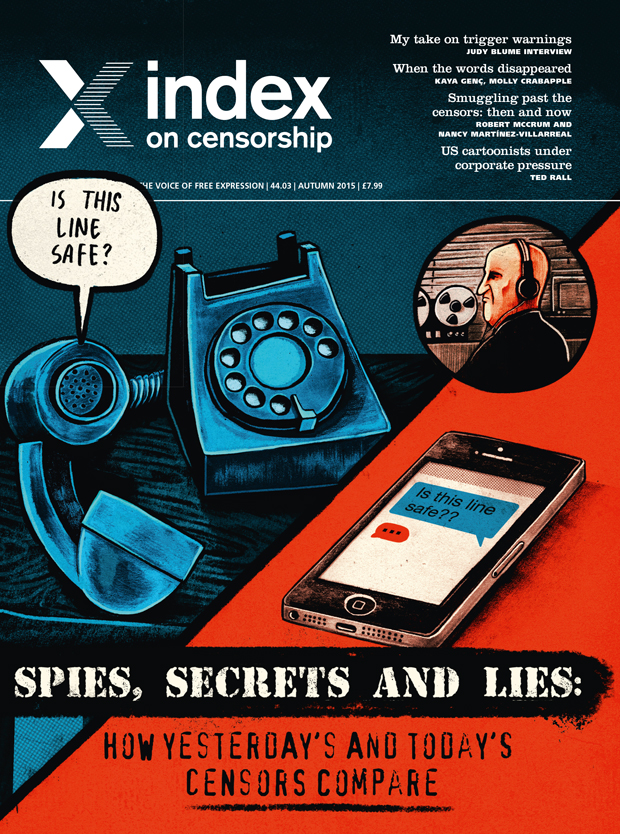

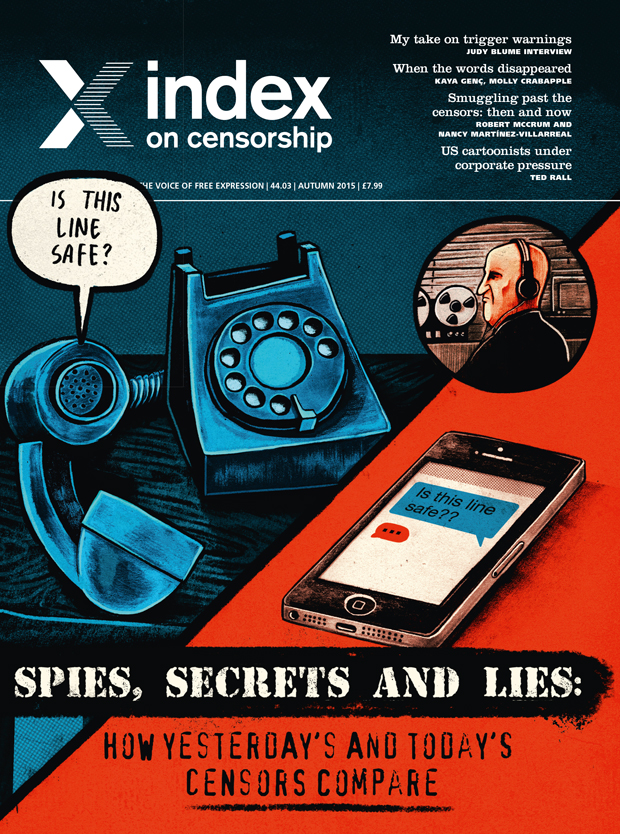

9 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

Post-Soviet Union, after the fall of the Berlin wall, after the Bosnian war of the 1990s, and after South Africa’s apartheid, the world’s mood was positive. Censorship was out, and freedom was in.

But in the world of the new censors, governments continue to try to keep their critics in check, applying pressure in all its varied forms. Threatening, cajoling and propaganda are on one side of the corridor, while spying and censorship are on the other side at the Ministry of Silence. Old tactics, new techniques.

While advances in technology – the arrival and growth of email, the wider spread of the web, and access to computers – have aided individuals trying to avoid censorship, they have also offered more power to the authorities.

There are some clear examples to suggest that governments are making sure technology is on their side. The Chinese government has just introduced a new national security law to aid closer control of internet use. Virtual private networks have been used by citizens for years as tunnels through the Chinese government’s Great Firewall for years. So it is no wonder that China wanted to close them down, to keep information under control. In the last few months more people in China are finding their VPN is not working.

Meanwhile in South Korea, new legislation means telecommunication companies are forced to put software inside teenagers’ mobile phones to monitor and restrict their access to the internet.

Both these examples suggest that technological advances are giving all the winning censorship cards to the overlords.

But it is not as clear cut as that. People continually find new ways of tunnelling through firewalls, and getting messages out and in. As new apps are designed, other opportunities arise. For example, Telegram is an app, that allows the user to put a timer on each message, after which it detonates and disappears. New auto-encrypted email services, such as Mailpile, look set to take off. Now geeks among you may argue that they’ll be a record somewhere, but each advance is a way of making it more difficult to be intercepted. With more than six billion people now using mobile phones around the world, it should be easier than ever before to get the word out in some form, in some way.

When Writers and Scholars International, the parent group to Index, was formed in 1972, its founding committee wrote that it was paradoxical that “attempts to nullify the artist’s vision and to thwart the communication of ideas, appear to increase proportionally with the improvement in the media of communication”.

And so it continues.

When we cast our eyes back to the Soviet Union, when suppression of freedom was part of government normality, we see how it drove its vicious idealism through using subversion acts, sedition acts, and allegations of anti-patriotism, backed up with imprisonment, hard labour, internal deportation and enforced poverty. One of those thousands who suffered was the satirical writer Mikhail Zoshchenko, who was a Russian WWI hero who was later denounced in the Zhdanov decree of 1946. This condemned all artists whose work didn’t slavishly follow government lines. We publish a poetic tribute to Zoshchenko written by Lev Ozerov in this issue. The poem echoes some of the issues faced by writers in Russia today.

And so to Azerbaijan in 2015, a member of the Council of Europe (a body described by one of its founders as “the conscience of Europe”), where writers, artists, thinkers and campaigners are being imprisoned for having the temerity to advocate more freedom, or to articulate ideas that are different from those of their government. And where does Russia sit now? Journalists Helen Womack and Andrei Aliaksandrau write in this issue of new propaganda techniques and their fears that society no longer wants “true” journalism.

Plus ça change

When you compare one period with another, you find it is not as simple as it was bad then, or it is worse now. Methods are different, but the intention is the same. Both old censors and new censors operate in the hope that they can bring more silence. In Soviet times there was a bureau that gave newspapers a stamp of approval. Now in Russia journalists report that self-censorship is one of the greatest threats to the free flow of ideas and information. Others say the public’s appetite for investigative journalism that challenges the authorities has disappeared. Meanwhile Vladimir Putin’s government has introduced bills banning “propaganda” of homosexuality and promoting “extremism” or “harm to children”, which can be applied far and wide to censor articles or art that the government doesn’t like. So far, so familiar.

Censorship and threats to freedom of expression still come in many forms as they did in 1972. Murder and physical violence, as with the killings of bloggers in Bangladesh, tries to frighten other writers, scholars, artists and thinkers into silence, or exile. Imprisonment (for example, the six year and three month sentence of democracy campaigner Rasul Jafarov in Azerbaijan) attempts to enforces silence too. Instilling fear by breaking into individuals’ computers and tracking their movement (as one African writer reports to Index) leaves a frightening signal that the government knows what you do and who you speak with.

Also in this issue, veteran journalist Andrew Graham-Yool looks back at Argentina’s dictatorship of four decades ago, he argues that vicious attacks on journalists’ reputations are becoming more widespread and he identifies numerous threats on the horizon, from corporate control of journalistic stories to the power of the president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, to identify journalists as enemies of the state.

Old censors and new censors have more in common than might divide them. Their intentions are the same, they just choose different weapons. Comparisons should make it clear, it remains ever vital to be vigilant for attacks on free expression, because they come from all angles.

Despite this, there is hope. In this issue of the magazine Jamie Bartlett writes of his optimism that when governments push their powers too far, the public pushes back hard, and gains ground once more. Another of our writers Jason DaPonte identifies innovators whose aim is to improve freedom of expression, bringing open-access software and encryption tools to the global public.

Don’t miss our excellent new creative writing, published for the first time in English, including Russian poetry, an extract of a Brazilian play, and a short story from Turkey.

As always the magazine brings you brilliant new writers and writing from around the world. Read on.

© Rachael Jolley

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.

14 Aug 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

The Sport for Rights coalition condemns the conviction and harsh sentencing of Azerbaijani human rights defenders Leyla and Arif Yunus on 13 August by the Baku Court of Grave Crimes. After a trial marred by irregularities and due process violations, the court convicted the couple on politically motivated charges including illegal entrepreneurship, tax evasion, and fraud, and sentenced Leyla to 8.5 years in jail, and Arif to seven.

“These sentences are outrageous, and aimed purely at sanctioning the legitimate work of these two Azerbaijani human rights defenders. While the heavy sentences are no surprise, they serve to further undermine Azerbaijan’s complete disregard for the international standards of fair trial and due process”, said Souhayr Belhassen, FIDH Honorary President.

“The unprecedented speed with which the Yunus trial was carried out is appalling and tells us a lot about its quality. The judgment is full of inaccuracies due to a total lack of examination of the evidence provided. Violations of international standards of the right to a fair trial were obvious”, declared Gerald Staberock, Secretary General of OMCT.

Leyla, the Director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, and Arif, a historian and activist in his own right, were arrested in July and August 2014, following Leyla’s public calls for a boycott of the inaugural European Games, which were held in Baku in June 2015. Sport for Rights considered them ‘Prisoners of the Games. Leyla had also been working to compile a detailed list of cases of political prisoners, and was a strong advocate of fundamental freedoms, property rights, and peaceful resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

The couple have been held in separate facilities; Leyla in the Kurdakhani investigative detention unit, and Arif at the Ministry of National Security’s investigative prison. Leyla reported being mistreated on several occasions, and Arif reported poor conditions. Both Leyla and Arif suffer from serious health problems, which have sharply deteriorated in detention, and have caused delays during trial proceedings, including on the day of the verdict, when Arif fainted and was attended to by a doctor. Nonetheless, the authorities resisted calls for their release on humanitarian grounds, and the court rushed to issue a verdict.

“The health situation of Leyla and Arif Yunus is extremely worrying and deserves the highest attention of the international community. Whilst we are thankful for the international attention brought to the case by some voices, we remain concerned by the lack of action of the Council of Europe and the European Union. It is clear that the climate of fear has reached a new low with these sentences and the killing of journalist Rasim Aliyev”,said Ane Tusvik Bonde, Regional Manager for Eastern Europe and Caucasus of the Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF).

The Yunus’ conviction takes place amidst a broader human rights crackdown in Azerbaijan, in the aftermath of the European Games and the run-up to November’s parliamentary elections. The same week as the verdict in the Yunus’ case, journalist Khadija Ismayilova also stood trial, facing serious jail time on politically motivated charges, and Rasim Aliyev, journalist and Chairman of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, died in hospital after being severely beaten. With less than three months until the parliamentary elections, the Azerbaijani authorities seem determined to continue working aggressively to silence the few critical voices left in the country.

The Sport for Rights coalition reiterates its call for the immediate and unconditional release of Leyla and Arif Yunus, as well as the other jailed journalists and human rights defenders in Azerbaijan. Sport for Rights further calls for sustained international attention to the country and increased efforts to hold the Azerbaijani regime responsible for its human rights obligations in the pre-election environment and beyond.

Supporting organisations:

ARTICLE 19

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Civil Rights Defenders

Freedom Now

Front Line Defenders

Human Rights House Foundation

Index on Censorship

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN American Centre

Platform

Solidarity with Belarus Information Office

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

[smartslider2 slider=”35″]

[timeline src=”https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1_rMZeC8deu7lQgoJPEESF0IqNO9u7aVuESqWMualEJw/pubhtml” width=”620″ height=”600″ font=”Bevan-PotanoSans” maptype=”toner” lang=”en” ]

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.