18 Dec 2017 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish, Volume 46.01 Spring 2017 extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Los periodistas mexicanos son objeto de amenazas por parte de un gobierno corrupto y cárteles violentos, y no siempre pueden confiar en sus compañeros de oficio. Duncan Tucker nos lo cuenta.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Cientos de periodistas marchan en silencio en 2010 como protesta contra los secuestros, asesinatos y violencia ejercida contra los periodistas del país, John S. and James L. Knight/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

«Espero que el gobierno no se deje llevar por la tentación autoritaria de bloquear el acceso a internet y arrestar a activistas», contaba el bloguero y activista mexicano Alberto Escorcia a la revista de Index on Censorship.

Escorcia acababa de recibir una serie de amenazas por un artículo que había escrito sobre el reciente descontento social en el país. Al día siguiente, las amenazas se agravaron. Invadido por una sensación de ahogo y desprotección, comenzó a planear su huida del país.

Son muchas las personas preocupadas por el estado de la libertad de expresión en México. Una economía estancada, una moneda en caída libre, una sangrienta narcoguerra sin final a la vista, un presidente extremadamente impopular y la administración beligerante de Donald Trump recién instalada en EE.UU. al otro lado de la frontera están generado cada vez más presión a lo largo de 2017.

Una de las tensiones principales es el propio presidente de México. Los cuatro años que lleva Enrique Peña Nieto en el cargo han traído un parco crecimiento económico. También se está dando un resurgir de la violencia y de los escándalos por corrupción. En enero de este año, el índice de popularidad del presidente se desplomó al 12%.

Para más inri, los periodistas que han intentado informar sobre el presidente y sus políticas han sufrido duras represalias. Por ejemplo, 2017 comenzó con agitadas protestas en respuesta al anuncio de Peña Nieto de que habría un incremento del 20% en los precios de la gasolina. Días de manifestaciones, barricadas, saqueos y enfrentamientos con la policía dejaron al menos seis muertos y más de 1.500 arrestos. El Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas ha informado que los agentes de policía golpearon, amenazaron o detuvieron temporalmente a un mínimo de 19 reporteros que cubrían la agitación en los estados norteños de Coahuila y Baja California.

No solo se han silenciado noticias; también las han inventado. La histeria colectiva anegó la Ciudad de México a consecuencia de las legiones enteras de bots de Twitter que comenzaron a incitar a la violencia y a difundir información falsa sobre saqueos, cosa que provocó el cierre temporal de unos 20.000 comercios.

«Nunca he visto la ciudad de esa manera», confesó Escorcia por teléfono desde su casa en la capital. «Hay más policía de lo normal. Hay helicópteros volando sobre nosotros a todas horas y se escuchan sirenas constantemente. Aunque no ha habido saqueos en esta zona de la ciudad, la gente piensa que está sucediendo por todas partes».

Escorcia, que lleva siete años investigando el uso de bots en México, cree que las cuentas falsas de Twitter se utilizaron para sembrar el miedo y desacreditar y distraer la atención de las protestas legítimas contra la subida de la gasolina y la corrupción del gobierno. Dijo que había identificado al menos 485 cuentas que constantemente incitaban a la gente a «saquear Walmart».

«Lo primero que hacen es llamar a la gente a saquear tiendas, luego exigen que los saqueadores sean castigados y llaman a que se eche mano del ejército», explicó Escorcia. «Es un tema muy delicado, porque podría llevar a llamamientos a favor de la censura en internet o a arrestar activistas», añadió, apuntando que la actual administración ya ha pasado por un intento fallido de establecer legislación que bloquee el acceso a internet durante «acontecimientos críticos para la seguridad pública o nacional».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Días después de que el hashtag de «saquear Walmart» se hiciera viral, Benito Rodríguez, un hacker radicado en España, contó al periódico mexicano El Financiero que le habían pagado para convertirlo en trending topic. Rodríguez explicó que a veces trabaja para el gobierno mexicano y admitió que «tal vez» fuera un partido político el que le dio dinero para incitar al saqueo.

La administración de Peña Nieto lleva mucho tiempo bajo sospecha de utilizar bots con objetivos políticos. En una entrevista con Bloomberg el año pasado, el hacker colombiano Andrés Sepúlveda afirmaba que, desde 2005, lo habían contratado para influir en el resultado de nueve elecciones presidenciales de Latinoamérica. Entre ellas, las elecciones mexicanas de 2012, en las que asegura que el equipo de Peña Nieto le pagó para hackear las comunicaciones de sus dos rivales principales y liderar un ejército de 30.000 bots para manipular los trending topics de Twitter y atacar a los otros aspirantes. La oficina del presidente publicó un comunicado en el que negaba toda relación con Sepúlveda.

Los periodistas de México sufren también la amenaza de la violencia de los cárteles. Mientras investigaba Narcoperiodismo, su último libro, Javier Valdez —fundador del periódico Ríodoce— se dio cuenta de lo habitual que es hoy día que en las ruedas de prensa de los periódicos locales haya infiltrados chivatos y espías de los cárteles. «El periodismo serio y ético es muy importante en tiempos conflictivos, pero desgraciadamente hay periodistas trabajando con los narcos», relató a Index. «Esto ha complicado mucho nuestra labor. Ahora tenemos que protegernos de los policías, de los narcos y hasta de otros reporteros».

Valdez conoce demasiado bien los peligros de incordiar al poder. Ríodoce tiene su sede en Sinaloa, un estado en una situación sofocante cuya economía gravita alrededor del narcotráfico. «En 2009 alguien arrojó una granada contra la oficina de Ríodoce, pero solo ocasionó daños materiales», explicó. «He recibido llamadas telefónicas en las que me ordenaban que dejase de investigar ciertos asesinatos o jefes narcos. He tenido que suprimir información importante porque podrían matar a mi familia si la mencionaba. Algunas de mis fuentes han sido asesinadas o están desaparecidas… Al gobierno le da absolutamente igual. No hace nada por protegernos. Se han dado, y se dan, muchos casos».

Pese a los problemas comunes a los que se enfrentan, Valdez lamenta que haya poco sentido de la solidaridad entre los periodistas mexicanos, así como escaso apoyo de la sociedad en general. Además, ahora que México se pone en marcha de cara a las elecciones presidenciales del año que viene y continúa peleándose con sus problemas económicos, teme que la presión sobre los periodistas no haga más que intensificarse, cosa que acarreará graves consecuencias al país.

«Los riesgos para la sociedad y la democracia son extremadamente graves. El periodismo puede impactar enormemente en la democracia y en la conciencia social, pero cuando trabajamos bajo tantas amenazas, nuestro trabajo nunca es tan completo como debería», advirtió Valdez.

Si no se da un cambio drástico, México y sus periodistas se enfrentan a un futuro aún más sombrío, añadió: «No veo una sociedad que se plante junto a sus periodistas y los proteja. En Ríodoce no tenemos ningún tipo de ayuda por parte de empresarios para financiar proyectos. Si terminásemos en bancarrota y tuviésemos que cerrar, nadie haría nada [por ayudar]. No tenemos aliados. Necesitamos más publicidad, suscripciones y apoyo moral, pero estamos solos. No sobreviviremos mucho más tiempo en estas circunstancias».

Escorcia, que se enfrenta a una situación igualmente difícil, comparte su sentido de la urgencia. Sin embargo, se mantiene desafiante, como en el tuit que publicó tras las últimas amenazas que recibió: «Este es nuestro país, nuestro hogar, nuestro futuro, y solo construyendo redes podemos salvarlo. Diciendo la verdad, uniendo a la gente, creando nuevos medios de comunicación, apoyando a los que ya existen, haciendo público lo que quieren censurar. Así es como realmente podemos ayudar».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Escucha la entrevista a Duncan Tucker en el podcast de Index on Censorship en Soundcloud, soundcloud.com/indexmagazine

Duncan Tucker es un periodista freelance que vive y trabaja en Guadalajara, México.

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista de Index on Censorship en primavera de 2017.

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The big squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Dec 2017 | About Index, History, Magazine, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The first editor of Index on Censorship magazine reflects on the driving forces behind its founding in 1972″ google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]A version of this article first appeared in Index on Censorship magazine in December 1981. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

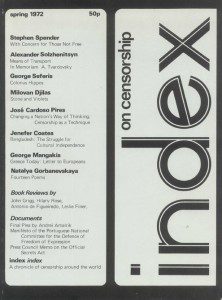

The first issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, 1972

Starting a magazine is as haphazard and uncertain a business as starting a book-who knows what combination of external events and subjective ideas has triggered the mind to move in a particular direction? And who knows, when starting, whether the thing will work or not and what relation the finished object will bear to one’s initial concept? That, at least, was my experience with Index, which seemed almost to invent itself at the time and was certainly not ‘planned’ in any rational way. Yet looking back, it is easy enough to trace the various influences that brought it into existence.

It all began in January 1968 when Pavel Litvinov, grandson of the former Soviet Foreign Minister, Maxim Litvinov, and his Englis wife, Ivy, and Larisa Bogoraz, the former wife of the writer, Yuli Daniel, addressed an appeal to world public opinion to condemn the rigged trial of two young writers and their typists on charges of ‘anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda’ (one of the writers, Alexander Ginzburg, was released from the camps in 1979 and now lives in Paris: the other, Yuri Galanskov, died in a camp in 1972). The appeal was published in The Times on 13 January 1968 and evoked an answering telegram of support and sympathy from sixteen English and American luminaries, including W H Auden, A J Ayer, Maurice Bowra, Julian Huxley, Mary McCarthy, Bertrand Russell and Igor Stravinsky.

The telegram had been organised and dispatched by Stephen Spender and was answered, after taking eight months to reach its addressees, by a further letter from Litvinov, who said in part: ‘You write that you are ready to help us “by any method open to you”. We immediately accepted this not as a purely rhetorical phrase, but as a genuine wish to help….’ And went on to indicate the kind oh help he had in mind:

My friends and I think it would be very important to create an international committee or council that would make it its purpose to support the democratic movement in the USSR. This committee could be composed of universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities from England, the United States, France, Germany and other western countries, and also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, in the future, even from Eastern Europe…. Of course, this committee should not have an anti-communist or anti-Soviet character. It would even be good if it contained people persecuted in their own countries for pro-communist or independent views…. The point is not that this or that ideology is not correct, but that it must not use force to demonstrate its correctness.

Stephen Spender took up this idea first with Stuart Hampshire (the Oxford philosopher), a co-signatory of the telegram, and with David Astor (then editor of the Observer), who joined them in setting up a committee along the lines suggested by Litvinov (among its other members were Louis Blom-Cooper, Edward Crankshaw, Lord Gardiner, Elizabeth Longford and Sir Roland Penrose, and its patrons included Dame Peggy Ashcroft, Sir Peter Medawar, Henry Moore, Iris Murdoch, Sir Michael Tippett and Angus Wilson). It was not, admittedly, as international as Litvinov had suggested, but it was thought more practical to begin locally, so to speak, and to see whether or not there was something in it before expanding further. Nevertheless, the chosen name for the new organisation, Writers and Scholars International, was an earnest of its intentions, while its deliberate echo of Amnesty International (then relatively modest in size) indicated a feeling that not only literature but also human rights would be at issue.

By now it was 1971 and in the spring of that year the committee advertised for a director, held a series of interviews and offered me the job. There was no programme, other than Litvinov’s letter, there were no premises or staff, and there was very little money, but there were high hopes and enthusiasm.

It was at this point that some of the subjective factors I mentioned earlier began to come into play. Litvinov’s letter had indicated two possible forms of action. One was the launching of protests to ‘support and defend’ people who were being persecuted for their civic and literary activities in the USSR. The other was to ‘provide information to world public opinion’ about this state of affairs and to operate with ‘some sort of publishing house’. The temptation was to go for the first, particularly since Amnesty was setting such a powerful example, but precisely because Amnesty (and the International PEN Club) were doing such a good job already, I felt that the second option would be the more original and interesting to try. Furthermore, I knew that two of our most active members, Stephen Spender and Stuart Hampshire, on the rebound from Encounter after disclosures of CIA funding, had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine, and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line. And finally, my own interests lay mainly in that direction. My experience had been in teaching, writing, translating and broadcasting. Psychologically I was too much of a shrinking violet to enjoy kicking up a fuss in public. I preferred argument and debate to categorical statements and protest, the printed page to the soapbox; I needed to know much more about censorship and human rights before having strong views of my own.

At that stage I was thinking in terms of trying to start some sort of alternative or ‘underground’ (as the term was misleadingly used) newspaper – Oz and the International Times were setting the pace were setting the pace in those days, with Time Out just in its infancy. But a series of happy accidents began to put other sorts of material into my hands. I had been working recently on Solzhenitzin and suddenly acquired a tape-recording with some unpublished poems in prose on it. On a visit to Yugoslavia, I called on Milovan Djilas and was unexpectedly offered some of his short stories. A Portuguese writer living in London, Jose Cardoso Pires, had just written a first-rate essay on censorship that fell into my hands. My friend, Daniel Weissbort, editor of Modern Poetry in Translation, was working on some fine lyrical poems by the Soviet poet, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, then in a mental hospital. And above all I stumbled across the magnificent ‘Letter to Europeans’ by the Greek law professor, George Mangakis, written in one of the colonels’ jails (which I still consider to be one of the best things I have ever published). It was clear that these things wouldn’t fit very easily into an Oz or International Times, yet it was even clearer that they reflected my true tastes and were the kind of writing, for better or worse, that aroused my enthusiasm. At the same time I discovered that from the point of view of production and editorial expenses, it would be far easier to produce a magazine appearing at infrequent intervals, albeit a fat one, than to produce even the same amount of material in weekly or fortnightly instalments in the form of a newspaper. And I also discovered, as Anthony Howard put it in an article about the New Statesman, that whereas opinions come cheap, facts come dear, and facts were essential in an explosive field like human rights. Somewhat thankfully, therefore, my one assistant and I settled for a quarterly magazine.

There is no point, I think, in detailing our sometimes farcical discussions of a possible title. We settled on Index (my suggestion) for what seemed like several good reasons: it was short; it recalled the Catholic Index Librorum Prohibitorum; it was to be an index of violations of intellectual freedom; and lastly, so help me an index finger pointing accusingly at the guilty oppressors – we even introduced a graphic of a pointing finger into our early issues. Alas, when we printed our first covers bearing the bold name of Index (vertically to attract attention nobody got the point (pun unintended). Panicking, we hastily added the ‘on censorship’ as a subtitle – Censorship had been the title of an earlier magazine, by then defunct – and this it has remained ever since, nagging me with its ungrammatically (index of censorship, surely) and a standing apology for the opacity of its title. I have since come to the conclusion that it is a thoroughly bad title – Americans, in particular, invariably associate it with the cost of living and librarians with, well indexes. But it is too late to change now.

Our first issue duly appeared in May 1972, with a programmatic article by Stephen Spender (printed also in the TLS) and some cautious ‘Notes’ by myself. Stephen summarised some of the events leading up to the foundation of the magazine (not naming Litvinov, who was then in exile in Siberia) and took freedom and tyranny as his theme:

Obviously there is a risk of a magazine of this kind becoming a bulletin of frustration. However, the material by writers which is censored in Eastern Europe, Greece, South Africa and other countries is among the most exciting that is being written today. Moreover, the question of censorship has become a matter of impassioned debate; and it is one which does not only concern totalitarian societies.

I contented myself with explaining why there would be no formal programme and emphasised that we would be feeling our way step by step. ‘We are naturally of the opinion that a definite need {for us} exists….But only time can tell whether the need is temporary or permanent—and whether or not we shall be capable of satisfying it. Meanwhile our aims and intentions are best judged…by our contents, rather than by editorials.’

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”My friends and I think it would be very important to create an international committee or council that would make it its purpose to support the democratic movement in the USSR.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In the course of the next few years it became clear that the need for such a magazine was, if anything, greater than I had foreseen. The censorship, banning and exile of writers and journalists (not to speak of imprisonment, torture and murder) had become commonplace, and it seemed at times that if we hadn’t started Index, someone else would have, or at least something like it. And once the demand for censored literature and information about censorship was made explicit, the supply turned out to be copious and inexhaustible.

One result of being inundated with so much material was that I quickly learned the geography of censorship. Of course, in the years since Index began, there have been many changes. Greece, Spain, and Portugal are no longer the dictatorships they were then. There have been major upheavals in Poland, Turkey, Iran, the Lebanon, Pakistan, Nigeria, Ghana and Zimbabwe. Vietnam, Cambodia and Afghanistan have been silenced, whereas Chinese writers have begun to find their voices again. In Latin America, Brazil has attained a measure of freedom, but the southern cone countries of Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and Bolivia have improved only marginally and Central America has been plunged into bloodshed and violence.

Despite the changes, however, it became possible to discern enduring patterns. The Soviet empire, for instance, continued to maltreat its writers throughout the period of my editorship. Not only was the censorship there highly organised and rigidly enforced, but writers were arrested, tried and sent to jail or labour camps with monotonous regularity. At the same time, many of the better ones, starting with Solzhenitsyn, were forced or pushed into exile, so that the roll-call of Russian writers outside the Soviet Union (Solzhenitsyn, Sinyavksy, Brodsky, Zinoviev, Maximov, Voinovich, Aksyonov, to name but a few) now more than rivals, in talent and achievement, those left at home. Moreover, a whole array of literary magazines, newspapers and publishing houses has come into existence abroad to serve them and their readers.

In another main black spot, Latin America, the censorship tended to be somewhat looser and ill-defined, though backed by a campaign of physical violence and terror that had no parallel anywhere else. Perhaps the worst were Argentina and Uruguay, where dozens of writers were arrested and ill-treated or simply disappeared without trace. Chile, despite its notoriety, had a marginally better record with writers, as did Brazil, though the latter had been very bad during the early years of Index.

In other parts of the world, the picture naturally varies. In Africa, dissident writers are often helped by being part of an Anglophone or Francophone culture. Thus Wole Soyinka was able to leave Nigeria for England, Kofi Awoonor to go from Ghana to the United States (though both were temporarily jailed on their return), and French-speaking Camara Laye to move from Guinea to neighbouring Senegal. But the situation can be more complicated when African writers turn to the vernacular. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who has written some impressive novels in English, was jailed in Kenya only after he had written and produced a play in his native Gikuyu.

In Asia the options also tend to be restricted. A mainland Chinese writer might take refuge in Hong Kong or Taiwan, but where is a Taiwanese to go? In Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, the possibilities for exile are strictly limited, though many have gone to the former colonising country, France, which they still regard as a spiritual home, and others to the USA. Similarly, Indonesian writers still tend to turn to Holland, Malaysians to Britain, and Filipinos to the USA.

In documenting these changes and movements, Index was able to play its small part. It was one of the very first magazines to denounce the Shah’s Iran, publishing as early as 1974 an article by Sadeq Qotbzadeh, later to become Foreign Minister in Ayatollah Khomeini’s first administration. In 1976 we publicised the case of the tortured Iranian poet, Reza Baraheni, whose testimony subsequently appeared on the op-ed page of the New York Times. (Reza Baraheni was arrested, together with many other writers, by the Khomeini regime on 19 October 1981.) One year later, Index became the publisher of the unofficial and banned Polish journal, Zapis, mouthpiece of the writers and intellectuals who paved the way for the present liberalisation in Poland. And not long after that it started putting out the Czech unofficial journal, Spektrum, with a similar intellectual programme. We also published the distinguished Nicaraguan poet, Ernesto Cardenal, before he became Minister of Education in the revolutionary government, and the South Korean poet, Kim Chi-ha, before he became an international cause célèbre.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Looking back, not only over the thirty years since Index was started, but much further, over the history of our civilisation, one cannot help but realise that censorship is by no means a recent phenomenon.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

One of the bonuses of doing this type of work has been the contact, and in some cases friendship, established with outstanding writers who have been in trouble: Solzhenitsyn, Djilas, Havel, Baranczak, Soyinka, Galeano, Onetti, and with the many distinguished writers from other parts of the world who have gone out of their way to help: Heinrich Böll, Mario Vargas Llosa, Stephen Spender, Tom Stoppard, Philip Roth—and many other too numerous to mention. There is a kind of global consciousness coming into existence, which Index has helped to foster and which is especially noticeable among writers. Fewer and fewer are prepared to stand aside and remain silent while their fellows are persecuted. If they have taught us nothing else, the Holocaust and the Gulag have rubbed in the fact that silence can also be a crime.

The chief beneficiaries of this new awareness have not been just the celebrated victims mentioned above. There is, after all, an aristocracy of talent that somehow succeeds in jumping all the barriers. More difficult to help, because unassisted by fame, are writers perhaps of the second or third rank, or young writers still on their way up. It is precisely here that Index has been at its best.

Such writers are customarily picked on, since governments dislike the opprobrium that attends the persecution of famous names, yet even this is growing more difficult for them. As the Lithuanian theatre director, Jonas Jurasas, once wrote to me after the publication of his open letter in Index, such publicity ‘deprives the oppressors of free thought of the opportunity of settling accounts with dissenters in secret’ and ‘bears witness to the solidarity of artists throughout the world’.

Looking back, not only over the years since Index was started, but much further, over the history of our civilisation, one cannot help but realise that censorship is by no means a recent phenomenon. On the contrary, literature and censorship have been inseparable pretty well since earliest times. Plato was the first prominent thinker to make out a respectable case for it, recommending that undesirable poets be turned away from the city gates, and we may suppose that the minstrels and minnesingers of yore stood to be driven from the castle if their songs displeased their masters. The examples of Ovid and Dante remind us that another old way of dealing with bad news was exile: if you didn’t wish to stop the poet’s mouth or cover your ears, the simplest solution was to place the source out of hearing. Later came the Inquisition, after which imprisonment, torture and execution became almost an occupational hazard for writers, and it is only in comparatively recent times—since the eighteenth century—that scribblers have fought back and demanded an unconditional right to say what they please. Needless to say, their demands have rarely and in few places been met, but their rebellion has resulted in a new psychological relationship between rulers and ruled.

Index, of course, ranged itself from the very first on the side of the scribblers, seeking at all times to defend their rights and their interests. And I would like to think that its struggles and campaigns have borne some fruit. But this is something that can never be proved or disproved, and perhaps it is as well, for complacency and self-congratulation are the last things required of a journal on human rights. The time when the gates of Plato’s city will be open to all is still a long way off. There are certainly many struggles and defeats still to come—as well, I hope, as occasional victories. When I look at the fragility of Index‘s a financial situation and the tiny resources at its disposal I feel surprised that it has managed to hold out for so long. No one quite expected it when it started. But when I look at the strength and ambitiousness of the forces ranged against it, I am more than ever convinced that we were right to begin Index in the first place, and that the need for it is as strong as ever. The next ten years, I feel, will prove even more eventful than the ten that have gone before.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Michael Scammell was the editor of Index on Censorship from 1972 to August 1980.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Nov 2017 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Nedim Türfent has been under detention for more than 18 months. The 5th hearing of his trial will be heard on Dec. 15 at the Hakkari Courthouse. © Mezopotamya Agency

“If we wanted to do, we could kill you right here and then say you were killed during the incidents. No one would be able to prove otherwise.”

That’s what police officers told journalist Nedim Türfent when they arrested him more than 18 months ago.

During the fourth hearing in his trial in the southeastern province of Hakkari on Friday 17 Nov, Türfent, a local correspondent and English news editor for the Dicle News Agency, informed the court about the abusive treatment he had suffered at the hands of authorities. The case had already attracted attention after 19 of 20 witnesses confessed to testifying against Türfent under torture and duress.

Türfent’s description of overt police threats has added more insult to injury in a case that lacks any evidence other than fallacious testimonies. “Don’t worry, we’re going to prepare such a file on you that you’ll be in for at least 20 years. You won’t be getting out anytime soon,” Türfent quoted police as saying during his hearing. The journalist faces up to 22.5 years in prison on charges of “membership in a terrorist organisation” and “conducting propaganda.” His 18 months in detention could be extended further in the next hearing on 15 Dec.

The fierce crackdown on Turkey’s mainstream media has been covered widely. But this has also created a certain “butterfly effect.” As the government dares to imprison renowned journalists in the “west” – Istanbul – the knock-on effect is much greater for Kurdish journalists in the east as they are sent back in time to face the dark spectres of the 1990s: intimidation, death threats, detentions and ill-treatment. The retaliation against Türfent for his journalistic work in his hometown of Yüksekova is one compelling example.

Yüksekova – Gever to the Kurdish locals – sits on a small flat plain that is surrounded by majestic and jagged peaks that pierce the sky. Located in Hakkari, which borders Iraq and Iran, it is the largest urban area in the country’s deprived southeastern corner. Toughened by the landscape, people from Gever are known to be self-resilient, proud and stubbornly uncompromising against any type of pressure – be it extreme weather or government crackdown. The same can be said for Türfent’s journalism. His bold coverage of the military siege and crackdown in the town in March-April 2016 made him a target.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yu5HL0b2GwE”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]One of Türfent’s stories received country-wide media attention when it revealed footage of a commander of special forces inflicting ill-treatment on a group of detainees. “You will see the power of the Turk,” the commander shouted. The story made a tremendous impact, with the prime ministry announcing that it would open a probe over the images.

But then came the death threats, harassment and, eventually, detention for the journalist who broke the story.

“Nedim is being punished for relating the state oppression in Yüksekova during the curfews,” said Nimet Ölmez, a fellow reporter with Mezopotamya Agency, the latest iteration of Dicle News Agency after it and its successor, Dihaber, were closed by decree. “Nedim didn’t have a weapon, a stick or a stone in his hands. All he had was a camera and a pen.”

Nedim Türfent’s parents and Diyarbakır-based Free Journalist Society co-chair Hakkı Boltan (R) pose at the Hakkari Courthouse during the fourth hearing of the trial on Nov. 17, 2017 in Hakkari, Turkey. © Özgün Özçer

Fethi Balaman, who started covering the news in Yüksekova for Mezopotamya months after Türfent was detained, explained how his colleague’s work kept the authorities under scrutiny.

“He had a huge network and he could reach anywhere. That scared them. This is why he started to receive more and more threats,” he said. “For instance, they knew that if there was a raid somewhere, Nedim would be informed. What did they do then? They took him so they could do anything they wanted.”

Türfent, who answered our questions from prison through a lawyer, Deniz Yıldız, stressed that it was not just himself but all journalists in the region who were being subject to pressure – pressure that continues even in jail. “As journalists who work in the region, we continuously encounter the cold face of the state when we are outside of prison. The same practices are also reflected once inside.”

More than 200 ongoing cases

Indeed, though compelling, Türfent’s case is just one of many lawsuits against Kurdish journalists. More than 200 probes have been opened against regional journalists, according to Diyarbakır-based Free Journalist Society co-chair Hakkı Boltan.

One of them is Dihaber reporter Selman Keleş, who was detained for taking pictures of Van’s Municipality building after it was surrounded with concrete blocks. Dihaber reporter Mehmet Güleş was also recently sentenced to nine years for “being a member of a terrorist organization” and “conducting propaganda.” Güleş had irritated authorities by reporting about the army’s destruction of homes in his hometown of Şırnak.

Balaman explained that he sometimes has to pass three checkpoints to cover a routine news story. Reporters cannot use a camera anymore, as police and soldiers confiscate them whenever they see one. “When I use a camera, I think about protecting it before protecting myself.”

Türfent is asking for more public awareness and support for the many Kurdish journalists who work across the region. “Our colleagues in the west are confronted with trumped-up indictments. But they have the possibility of moulding public opinion. Journalists who work [here], especially in remote places such as Yüksekova and Cizre, remain in the background.”

The fate of such journalists is a litmus test for defenders of press freedom given the lack of public attention for their plight. “Many colleagues are still waiting for a trial to start two years [after they were detained]. However, there isn’t even a small news story about them,” Türfent said.

Through months of military siege and a state of emergency, local reporters have braved authorities to report on killings, destruction and atrocities that would have been concealed if not for the journalists’ work. But ultimately, the question goes beyond freedom of expression; now, it is the very essence of truth that is at stake.

“Understanding the causes and the results of the Nedim Türfent case means understanding the necessity of freedom for journalists,” said Boltan, demanding more support for Kurdish journalists. “The violations committed here are the source of the pressure on the mainstream media.”

Destruction is still visible in some areas of Yüksekova more than a-year-and-a-half after the military siege. © Özgün Özçer

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified over 3,600 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]