27 Jun 2025 | Africa, Americas, Asia and Pacific, Australia, Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, Israel, Kenya, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Palestine, United States

In the age of online information, it can feel harder than ever to stay informed. As we get bombarded with news from all angles, important stories can easily pass us by. To help you cut through the noise, every Friday Index publishes a weekly news roundup of some of the key stories covering censorship and free expression. This week, we look at Hungary’s banned Pride demonstration, and mass anti-government protests in Kenya.

Pride in spite of the law: Hungary’s LGBTQ+ march to go ahead in violation of police ban

On Tuesday 18 March, Hungary’s ruling Fidesz party led by Viktor Orbán rushed a bill through parliament banning LGBTQ+ pride marches, sparking outrage from the EU and activists. The ban was made on the grounds that such events are allegedly harmful to children, with Orbán stating “We won’t let woke ideology endanger our kids.” This put Budapest’s annual Pride march, scheduled to take place on Saturday 28 June, in jeopardy – but Hungary’s LGBTQ+ community is refusing to back down.

The march, which marks the 30th anniversary of Budapest Pride, is scheduled to go ahead with backing from Budapest’s liberal mayor, who has taken the step of organising the event through the city council under the name “Day of Freedom” to circumvent the law against LGBTQ+ gatherings – but the city police, still under the control of Fidesz, will be moving to quash these efforts. Those partaking in the event will be targeted by facial recognition technology and could face fines. With more than 200 Amnesty International delegates set to march alongside thousands of Hungarians in solidarity, Saturday is likely to see a clash between Hungary’s LGBTQ+ community and the state police.

Brutality begets brutality: Kenyan protests against government cruelty result in further loss of life

On 25 June 2024, a mass protest outside parliament in Nairobi against tax rises escalated into a tragedy, with Kenyan police officers firing on protesters as they attempted to storm the parliament building. The Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights announced that 39 had been killed in the nationwide demonstrations, and it was recently revealed by BBC Africa Eye that some officers had shot and killed unarmed protesters. Marking a year since this incident, Kenyans took to the streets this week to demonstrate against the government, and further brutality has followed.

Amnesty International Kenya has reported that 16 people were killed at the anniversary protests on 25 June 2025, with approximately a further 400 injured. CNN witnessed police firing live ammunition to disperse peaceful protesters, and the government regulator, Communications Authority of Kenya, issued an order for all local TV and radio stations to stop broadcasting live coverage of the protests. Tensions have been on the rise in recent months, with the murder of Kenyan blogger Albert Ojwang in police custody, and the shooting of street vendor Boniface Kariuki at a demonstration in Ojwang’s honour inflaming the situation further.

Free at last: Pro-Palestinian student activist Mahmoud Khalil released

Palestinian-Algerian activist and Columbia University student Mahmoud Khalil was released from his detention in a Louisiana Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility on the evening of Friday 20 June after 104 days in detention.

Khalil’s arrest sparked a national outcry. A prominent pro-Palestinian activist on Columbia’s campus, he would sometimes act as a spokesperson for the student protest movement, making him a prime target for ICE’s crackdown on immigrant protesters – despite Khalil holding a green card, which grants an individual lawful permanent resident status in the USA.

He was arrested without a warrant on 8 March 2025. Charged with no crime, Khalil was earmarked for deportation by Secretary of State Marco Rubio under the belief that his presence in the country had “foreign policy consequences”. This move was deemed unconstitutional, and Khalil was released after a Louisiana judge ruled that Khalil was neither a flight risk nor dangerous, and that his prolonged detention – which led to him missing the birth of his son – was potentially punitive.

Khalil returned to the frontlines of protests just days after his release, but his feud with the Donald Trump administration is far from over. The government is reportedly set to appeal the ruling to release Khalil, and rights groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have suggested that there could be a long legal road ahead.

Unfairly dismissed: Australian journalist wins court case after losing her job over Gaza repost

Australian journalist Antoinette Lattouf has won her court case against Australia’s national broadcaster, Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), with a judge ruling she was unfairly dismissed from her job after sharing a post on social media about the Israel-Gaza conflict.

Lattouf reportedly shared a post by Human Rights Watch that accused Israel of committing war crimes in Gaza in December 2023, resulting in her sacking from her fill-in radio presenter role just hours later.

ABC claimed that the post violated its editorial policy, but after the ruling has apologised to the journalist, saying it had “let down our staff and audiences” in how it handled the matter. According to The Guardian, the broadcaster had received a “campaign of complaints” from the moment Lattouf was first on air, accusing her of anti-Israel bias based on her past social media activity. It has also been reported that due process around Lattouf’s dismissal was not followed, with the allegations in the email complaints not put to her directly prior to her sacking.

Justice Darryl Rangiah ruled that Lattouf had been fired “for reasons including that she held a political opinion opposing the Israeli military campaign in Gaza”, in violation of Australia’s Fair Work Act. Lattouf was awarded 70,000 Australian dollars ($45,000) in damages. She told reporters outside the courtroom “I was punished for my political opinion”.

Sudden freedom: 14 Belarusian political prisoners freed from prison following US official visit

During the visit of the US special envoy Keith Kellogg to Belarus’s capital Minsk, dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka made the surprise move of releasing 14 political prisoners from detention on 21 June 2025. The US brokered deal, reportedly led by Kellogg, saw the release of prominent Belarusian activist Siarhei Tsikhanouski who was arrested in 2020 and sentenced with 18 years in prison after declaring his intention to run for president. Also released was journalist Ihar Karnei who worked at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty for more than 20 years.

Tsikhanouski has recounted his experience in prison as being “torture”. He said he was kept in solitary confinement and denied adequate food and medical care, and he lost more than 100 pounds during his five years’ imprisonment. He told the Associated Press that prison officials would mock him, saying “You will be here not just for the 20 years we’ve already given you – we will convict you again” and “You will die here.”

Tsikhanouski is the husband of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who following his arrest took his place in running for president and became the main opposition leader in Belarus. Now living in exile in Lithuania, the two have been reunited in Vilnius – but Tsikhanouskaya insists that her work is not finished with reportedly more than 1,100 political prisoners still remaining inside Belarusian jails.

24 Jun 2025

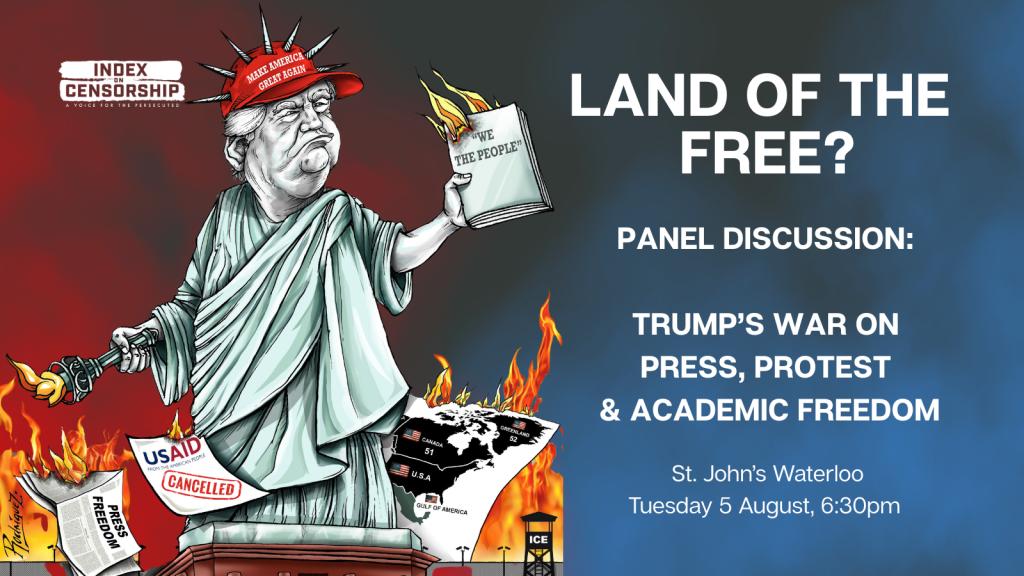

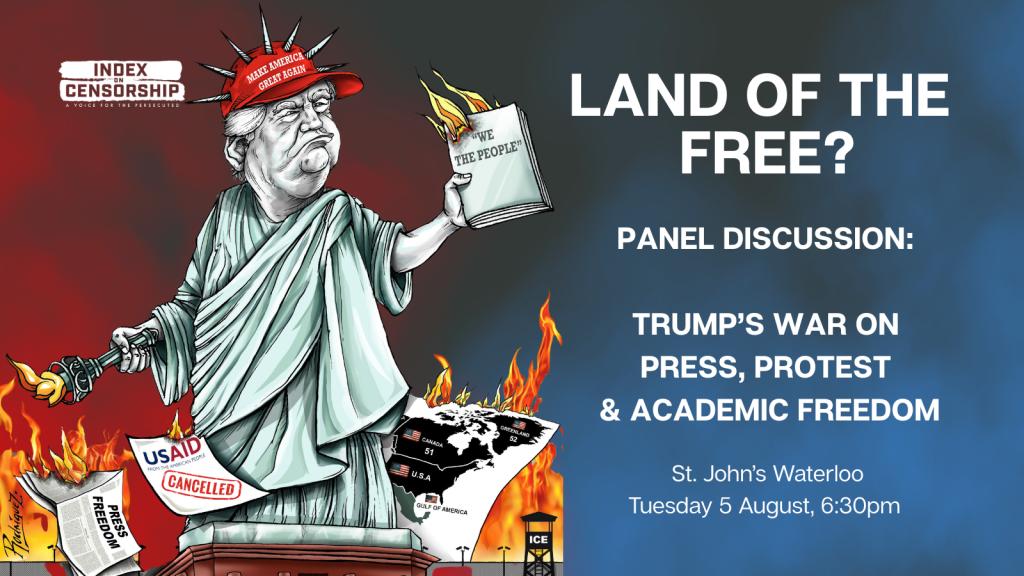

Since returning to office, Donald Trump has intensified efforts to crush dissent in the USA: cracking down on protest, targeting the press and threatening academic freedom. His campaign against free expression is sending shockwaves across the USA and beyond.

What does this mean for democracy, independent journalism, and the right to speak out?

Join us on Tuesday 5 August at St John’s Waterloo for the launch of Land of the Free?, the latest magazine issue by Index on Censorship. Come for a reception and panel discussion looking at the impact of the Trump administration on free speech in the USA, and the wider implications for the rest of the world.

Speakers to be announced soon.

About Index on Censorship

Index on Censorship is a UK-based charity dedicated to defending and promoting freedom of expression around the world. Founded in 1968 as Writers and Scholars International, we have a long and proud history of standing up for the right to speak, write, create and protest without fear. Read about the history of Index on Censorship

We publish the work of censored writers and artists, spotlight global threats to free speech, and foster debate on the value of freedom of expression. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of censorship, persecution or violence. Our mission is simple but vital: to raise awareness, challenge suppression and amplify voices that others try to silence.

Sponsored by Sage.

20 Jun 2025 | Cambodia, India, Iran, Israel, News and features, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, United Kingdom

In the age of online information, it can feel harder than ever to stay informed. As we get bombarded with news from all angles, important stories can easily pass us by. To help you cut through the noise, every Friday Index publishes a weekly news roundup of some of the key stories covering censorship and free expression. This week, we look at how Israel has targeted Iranian media in bombing strikes, and the state execution of a Saudi journalist.

Bombed live on broadcast: Israel strikes Iranian state media

In the early hours of Friday 13 June, Israel launched strikes against Iran which has since escalated into a larger conflict, with major population centres such as Tehran and Tel Aviv facing missile attacks. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu claims the initial attack, dubbed Operation Rising Lion, was pre-emptive to prevent Iran from producing a nuclear weapon which Israel believed was imminent – a claim that is not backed up by US intelligence. Beyond nuclear targets, Israeli missiles have targeted another facet of the Iranian state: the media.

On 16 June, the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting’s (IRIB) TV channel was broadcasting live news coverage of the conflict when an explosion rocked the studio, forcing the presenter to flee and the broadcast to cut to pre-recorded bulletins. Israel had bombed the studio live on air in a direct attack on Iranian media. Israeli defence minister Israel Katz described the attack as a strike on the “propaganda and incitement broadcasting authority of the Iranian regime“, while an Israeli military spokesperson alleged that IRIB was aiding the Iranian military “under the cover of civilian assets and infrastructure“. Iranian officials described the attack as a war crime, while the head of IRIB Peyman Jebelli stated that the studio was damaged, but vowed that broadcasting would return. Local media reported that three members of staff were killed in the attack, including a senior news editor.

“High treason” or Twitter?: Saudi journalist executed after social media posts

On 14 June 2025, the Saudi Interior Ministry announced on X that it had carried out the death penalty on Saudi journalist Turki al-Jasser, who stood accused of high treason and terrorism charges, in the first high-profile killing of a Saudi journalist since Jamal Khashoggi. But campaigners close to the case believe that the true reason for al-Jasser’s arrest and execution in 2018 was his posts made on X (then called Twitter).

Al-Jasser reportedly had two accounts: one under his real name, and a second, anonymous account that was critical of the Saudi government, accusing the Saudi royal family of corruption. The Saudi government is thought to have identified al-Jasser as someone involved with attempting to topple the government because of his posts; Saudi Arabia allegedly infiltrated Twitter’s databases to access information about anonymous users in 2014 and 2015, and could have identified Al-Jasser using a similar method. It has been reported that Al-Jasser, who founded the news website Al-Mashhad Al-Saudi (The Saudi Scene), was tortured during his seven-year detention.

Changing views: Reforms to freedom of expression on UK campuses

The university campus is often considered a battleground for free speech, with conflicting ideals constantly in debate and student protests making national news. Universities are often caught between supporting staff or students, and are frequently criticised for giving or denying controversial speakers a platform.

Following some high-profile incidents, universities have asked for clarity. Kathleen Stock, a philosophy professor at the University of Sussex, resigned in 2021 following protests on campus regarding her gender-critical views, for example. The Office for Students (OfS) fined the university £585,000 for the poor handling of her case and failing to uphold free speech.

A set of new OfS guidelines are intended to provide clear advice on what is permitted and what is not. In the guidelines, the OfS has ruled that universities in England will no longer be able to enforce blanket bans on student protests. This follows a wave of pro-Palestine student protests, with encampments appearing on university grounds across the country. Some universities have looked to prohibit such demonstrations, as Cambridge University did when a court ruled to block any further Israel-Palestine protests until the end of July.

The OfS guidelines also address the protection of viewpoints by staff and students that some may find offensive. Arif Ahmed, director for freedom of speech and academic freedom at OfS, stated that students “have to accept that other people will have views that you find uncomfortable” when attending university. The guidelines come into effect in UK universities on 1 August.

No more soap operas: Cambodia bans Thai TV in border dispute

Since a clash at a disputed border area between Cambodia and Thailand claimed the life of a Cambodian soldier on 28 May, the two southeast Asian nations have seen tensions escalate. Each side blamed the other for the skirmish, which has resulted in an increased armed presence at the border and the introduction of retaliatory measures by both governments. With neither side looking to back down, the Cambodian government has taken a further step to sever ties with its neighbour by banning Thai TV and movies from being shown in Cambodia.

The ban also includes a boycott of any Thai internet links; a move that Cambodia’s minister of post and telecommunication Chea Vandeth claimed would cost Thailand hundreds of millions of dollars. Every cinema in the country has been informed that import and screening of Thai films is strictly prohibited as of 13 June, and Thai TV broadcasts – such as Thai soap operas, which are especially popular in Cambodia – must be replaced with Chinese, Korean or Cambodian dramas. Tensions continue to rise, and Cambodia instituted a ban on Thai fruit imports on Tuesday.

Citizen journalism under fire: Government of Jammu and Kashmir has YouTubers and online content creators in their sights

The government of Jammu and Kashmir has issued an order targeting those it deems to be “impersonating journalists”, including content creators on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. The order restricts speech vaguely defined as “provocative” or “false” content, and content creators reporting on political affairs in the region could be classified as “impersonating a journalist”. The order comes with significant legal threats such as fines, imprisonment and the confiscation of electronic devices, allowing for anyone deemed to be “disrupting public order” to face consequences.

Threats to free speech in Jammu and Kashmir have been prevalent since a deadly terrorist attack in Indian-controlled Kashmir in April claimed 26 lives. Journalist Rakesh Sharma was physically assaulted while covering a protest in Jammu and Kashmir, and following the terrorist attack, the Indian government implemented widespread digital censorship on Pakistani and Muslim content on social media. With the new order, it will be even harder for residents of Jammu and Kashmir to stay informed.

4 Jun 2025 | News and features, United Kingdom

A growing number of UK journalists believe that the truth is shaped by those in power and many believe that media freedom in the country is at risk. UK journalists are also increasingly coming under attack for their work and are taking a more activist role in their reporting.

The findings are contained in a new report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and the University of Oxford, which is based on a survey conducted between September and November 2023 with a representative sample of 1,130 UK journalists.

The UK Journalists in the 2020s report revealed that almost half (48%) of journalists believe that “truth is inevitably shaped by those in power”. It also reveals that left-leaning journalists (55%) are more likely to agree with this than right-leaning ones (33%).

One of the report’s editors, Craig T Robertson, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Reuters Institute, said: “Journalists are in a key position to question those in power and try to get at the truth – it’s their job. For this reason, it may be somewhat surprising that almost half of UK journalists believed that ‘truth is inevitably shaped by those in power’. But this almost cynical feeling could come down to the fact that those in political power, especially, are difficult for journalists to work with.”

Another editor Jingrong Tong, a senior lecturer in media and information studies at the University of Sheffield, said: “It is worrying that, in total, 43% of respondents considered the UK news media to have only ‘some’, ‘little’, or ‘no media freedom’ at all. The divided views on media freedom echo the recent warnings signalled by observer groups such as Index on Censorship that the UK has already slid down to be only ‘partially open’”.

“Although UK journalists still considered their traditional roles as informers and watchdogs to be the most important, the emphasis they gave to these roles has shifted. Overall, the informer roles have decreased in importance, while watchdog roles have increased,” the report added.

Nearly three quarters of respondents (71%) found it very or extremely important to “counteract disinformation” and two thirds (65%) thought it very or extremely important to “shine a light on society’s problems”.

The growing threats to UK journalists are also laid bare by the report. It reveals that only 18% of UK journalists reported they had never experienced safety threats related to their work over the previous five years. The most frequent forms of safety threats experienced by journalists were “demeaning or hateful speech” (45% had experienced these at least “sometimes”), followed by “public discrediting” (39%) and “other forms of threats and intimidation” (16%). Gender was significant in journalists’ experience of safety threats. In the survey, 22% of women journalists had experienced sexual violence in the previous five years compared with only 4% of men. One in eight female journalists and one in twelve male journalists report that they had encountered demeaning or hateful speech often or very often.

The survey also suggests there is much work to be done in the UK to prevent journalists being threatened by powerful actors. Some 17% of journalists said they had been the subject of legal action because of their work. (Journalists facing legal threats can explore our new Am I facing a SLAPP tool here.)

The survey also reports that UK journalists are overwhelmingly privileged, white and university-educated and are increasingly left-leaning.

Of the 1,130 UK journalists surveyed, 90% were white, 91% had been to university and 71% came from a privileged background (as defined by their parents’ occupation).

Pete Clifton, former editor of BBC News and former editor-in-chief at PA Media, wrote in the foreword: “Despite so many people banging the drum for diverse newsrooms to cater for diverse audiences, the results make difficult reading once again.”

The survey reveals that the proportion of journalists from ethnic minority backgrounds has increased since the last survey was done in 2015 but the figures are still small compared to the general population: 3% of journalists are Asian (compared to 9% of the UK population in general) and 1.3% are Black (compared to 4%).

The survey also found that, as a group, UK journalists have moved further to the left since 2015. In 2015, around half (54%) identified with the political left, but this rose to three quarters (77%) by 2023.