6 May 2014 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

The shocking news of the death of democracy advocate and widely acclaimed Egyptian blogger, Bassem Sabry on April 29, hit me like a lightning bolt.

My short friendship with Bassem dates back to the early days of the January 25 uprising a little over three years ago when, without knowing me personally, Bassem had telephoned to congratulate me on quitting my job at Egypt’s state-run Nile TV in protest at the station’s biased coverage of the protests in Tahrir Square. Although we only met a couple of times after that conversation, I have since considered Bassem “a friend” mainly because of our shared aspirations for a better Egypt.

I learned of Bassem’s death from the flood of Twitter tributes to him from his friends, associates and fellow revolutionaries posted a couple of hours after he had passed away in what his family members describe as a “tragic accident.” Like many of his friends, I had hoped the Twitter eulogies were a sick joke. Unfortunately, they weren’t.

Bassem’s death was confirmed shortly afterward by news reports that said he had fallen to his death from a 10th floor balcony of his apartment after he reportedly “went into a diabetic coma”.

In an outpouring of love and grief, many of Bassem’s comrades in the struggle for a free and democratic Egypt — and some admirers who had never met him but who knew Bassem from his honest and insightful writings and commentaries on Egyptian politics, post-revolution — wrote moving eulogies to him on Twitter .

“Only the good die young but a great loss for those who still have hope for a better Egypt,” prominent human rights lawyer Ragia Omran said via her Twitter account.

“I never knew him but I knew his work. I saw the impact he had and his determination to make things better,” wrote Jeremy Walker, a journalist who has worked for the BBC World Service.

In other online tributes to Bassem, he was fittingly described as “an inspiration”, “a voice of reason”, “a true patriot” and “a champion of civil rights.” Highly respected for his reasoned analysis of regional politics for several international and local media outlets (including Al Monitor, Foreign Policy, the Huffington Post and the independent Egyptian daily Al Masry El Youm), Bassem’s ability to rise above the deeply divided political fray has earned him respect from across the political spectrum.

“I call on the youth of the revolution to pray for a companion and a noble person whom we lost,” exiled Nobel Peace Prize winner Mohamed ElBaradei said on Wednesday via his Twitter account. Bassem had briefly worked as a strategist for Al Dostour Party — the political party founded by ElBaradei after the January 2011 uprising. That however, did not stop him from criticizing the liberal politician’s “one foot inside, one foot outside” attitude vis-à-vis Egyptian politics, which Bassem deemed “frustrating to his supporters”.

Nader Bakkar, the spokesperson for the ultra-conservative Salafi Al Nour Party also expressed his condolences following Bassem’s death, describing him as “a moral person who loved his country”.

Bassem has also been hailed by analysts as a “voice of moderation and conciliation” — a title he deservingly earned for his repeated pleas for unity in the bitterly divided country. In an article published by Ahram Online on June 18, 2013 — just two weeks before Islamist President Mohamed Morsi was toppled by military-backed protests — Bassem had expressed his anxiety and frustration at the discord and deepening polarisation in Egypt. He wrote:

“It is utterly frustrating, disheartening and troubling to see where we are after more than two years of a revolution that was meant to end injustice, political exclusion and repression and hopefully unify most of the country around the dream of rebuilding a strong and vibrant nation. Instead, much of that injustice, exclusion and repression still exists. What’s worse, we’re more divided than ever as a people, and more exclusionary, while the voices of reconciliation and bridge-building are finding themselves more and more unpopular.”

In the same article, Bassem also expressed fear that the deep divisions in Egypt would lead to more blood-letting and violence in the months ahead.

“The fact that we are likely to see some violence and casualties on all sides fills me with dread,” he wrote, noting that clashes between Morsi supporters and opponents had already erupted in Fayoum and Menoufiya. Bassem’s fears were not unfounded: the country has since slipped into a spiral of violence and counter-violence with security forces using lethal force to disperse “anti-coup” protests and militants retaliating with attacks on military and security installations.

Meanwhile, an Arabic essay written by Bassem in October 2012 — around his 30th birthday — and which was published in the independent Al Masry El Youm, reflects his admirable traits of tolerance and compassion while demonstrating his strong urge to embrace all of humanity. In the essay titled Eleutheria, Bassem shared with readers the lessons that life had taught him. Many of those who have read the piece were amazed by the foresight and wisdom of someone so young. The essay was later translated into English and posted on his blog site, becoming one of the most read articles in 2012.

“I have met Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, the non-religious, the still-searching, and others. And I have met those of all skin colours. And I have found them to all be like myself. We became friends, and I became wealthier in spirit as a human being. And I learned that mankind was one, that coexistence was possible, that we must ostracise the hate-mongers amongst us. We can achieve with the pen and the word much more than what we can achieve with guns and loud angry rhetoric – and achieve that more rapidly ”

Unlike many Egyptian journalists who practice self-censorship in the current repressive climate of fear since the coup, Bassem had refused to be intimidated and had managed to remain neutral and objective throughout. He refused to take sides in the ongoing conflict between the military and the Muslim Brotherhood, designated as a terrorist organization in December. A few weeks ago when asked by a fellow journalist whose side he was on, he replied: “Nobody’s, I simply support my country.”

Close friends and secular activists describe him as “an optimist to a fault”. In recent months however, Bassem’s optimism had waned and he became increasingly frustrated with the political turmoil, violence and above all, with the military-backed government’s repressive policies. In a tribute to Bassem published in the independent news portal Mada Masr on Thursday, his friend H. A. Hellyer, a non-resident Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies in London and the Brookings Institution wrote: “Bassem at heart was a great optimist. However, and he was very reserved about this fact, he was deeply and terribly pained by the experience of particularly the last year. The pain he felt, as he saw Egyptian turn on Egyptian, troubled him tremendously. He lived to see the revolution that so many Egyptians of his generation wanted to be a part of — but he was also profoundly wounded to see the failure of Egyptians to live up to that revolution.”

Bassem himself had expressed his dismay at the turn of events in Egypt, post-revolution, blaming the messy transition on the lack of vision of the country’s political elite. In an article published by Ahram Online in June 2013, he lamented that “the political elites, on every side of the spectrum, have profoundly failed the nation in varying ways down the road through an astonishing alternation (or even, at times, a blend) of lack of vision, displays of ineptitude, an improper balance of idealism and pragmatism, inability to know when to lead the street and their political biases and when to defy them for a greater good if necessary, and more.”

I last met Bassem for dinner at a restaurant overlooking the Nile River in the affluent neighbourhood of Zamalek one week before his death. That evening, he did not drink and left his food untouched. I also noticed that he had lost his infectious vigour and enthusiasm; it was clear he had been weighed down by the news of daily killings and detentions of both secular activists and Muslim Brotherhood supporters, the targeting of journalists by security forces and the recent mass death sentences handed down to Morsi loyalists. We talked about the ongoing events and about the presidential elections scheduled for the end of this month. Bassem told me that he had joined leftist politician Hamdeen Sabahy’s presidential campaign. I was not surprised. After all, most young revolutionaries do not want to see Egypt return to oppressive military rule and Sabahy is the sole candidate contesting the presidential elections against Field Marshal Abdel Fattah El Sisi. Despite joining protests demanding the downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood regime in July 2013, many of them are waking up to the realization that their uprising has paved the way for the return of the old police state that existed under Hosni Mubarak. The jailing of prominent secular activists, the return of media censorship and the recent outlawing of the April 6 group — the movement that helped ignite the January 2011 mass protests — are all signs that the revolution has once again been stolen and that this is the counter-revolution, lament the young activists.

In a message posted on his Twitter account on March 24, 2013 Bassem had quizzed: “Why is it that all the good people die in this country?” He had posed the question in the wake of violent demonstrations against the Muslim Brotherhood and clashes between secular activists and Brotherhood supporters outside the Islamist group’s Cairo Headquarters. Earlier that same day, Morsi had warned he would take “necessary measures” against any politicians and Mubarak loyalists shown to be involved in the violence and rioting.

At the time, Bassem was probably unaware that his question was a premonition of his own death. It is a question that many of his young activist friends are echoing today.

“Why is it that all the good people die in this country?” Rest in Peace, Bassem. You will be sorely missed.

This article was posted on May 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 May 2014 | News and features

A London protest calling for the release of jailed Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt (Image: Index on Censorship)

Press freedom is at a decade low. Considering just a handful of the events of the past year — from Russian crackdowns on independent media and imprisoned journalists in Egypt, to press in Ukraine being attacked with impunity and government reactions to reporting on mass surveillance in the UK — it is not surprising that Freedom House have come to this conclusion in the latest edition of their annual press freedom report. This serves as a stark reminder that press freedom is a right we need to work continuously and tirelessly to promote, uphold and protect — both to ensure the safety of journalists and to safeguard our collective right to information and ability to hold those in power to account. On the eve of World Press Freedom day, we look back at some of the threats faced by the world’s press in the last 12 months.

1) Journalism is not terrorism…

National security has been used as an excuse to crack down on the press this year. “Freedom of information is too often sacrificed to an overly broad and abusive interpretation of national security needs, marking a disturbing retreat from democratic practices,” say Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in their recently released 2014 Press Freedom Index.

Journalists have faced terrorism and national security-related accusations in places known for their somewhat chequered relationship with press freedom, including Ethiopia and Egypt. However, the US and the UK, which have long prided themselves on respecting and protecting civil liberties, have also come under criticism for using such tactics — especially in connection to the ongoing revelations of government-sponsored mass surveillance.

American authorities have gone after former NSA contractor and whistleblower Edward Snowden, tapped the phones of Associated Press staff, and demanded that journalists, like James Risen, reveal their sources. British authorities, meanwhile, detained David Miranda under the country’s Terrorism Act. Miranda is the partner of Glenn Greenwald, the journalist who broke the mass surveillance story. Authorities also raided the offices of the Guardian — a paper heavily involved in reporting in the Snowden leaks.

2) …but governments still like putting journalists in prison

The Al Jazeera journalists detained in Egypt on terrorism-related charges was one of the biggest stories on attacks on press freedom this year. However, Mohamed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed, Peter Greste and their colleagues are far from the only journalists who will spend World Press Freedom Day behind bars. The latest prison census from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) put the number of journalists in jail for doing their job at 211 — their second highest figure on record.

In Bahrain, award-winning photographer Ahmed Humaidan was sentenced in March to ten years in prison. In Uzebekistan, Muhammad Bekjanov, editor of opposition paper Erk, is serving a 19-year sentence — which was increased from 15 in 2012, just as he was due to be released. In Turkey, after waiting seven years, Fusün Erdoğan, former general manager of radio station Özgür Radyo, was last November sentenced to life in jail. Just last Friday, Ethiopian authorities arrested prominent political journalist Tesfalem Waldyes and six bloggers and activists.

3) New media is under attack…

As more journalism is being conducted online, blogs, social and other new media are increasingly being targeted in the suppression of press freedom. Almost half of the world’s jailed journalists work for online outlets, according to the CPJ. China — with its massive censorship apparatus — has continued censoring microblogging site Sina Weibo, while also turning its attention to relative newcomer WeChat. In March, it closed down several popular accounts, including that of investigative journalist Luo Changping.

Meanwhile, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has publicly all but declared war on social media, at one point calling it the “worst menace to society”. Twitter played a big role in last summer’s Gezi Park protests, used by journalists and other protesters alike. Only days ago, Turkish journalist Önder Aytaç was jailed, essentially, because of the letter “k” in a Tweet.

Meanwhile Russia has seen a big crackdown on online news outlets, while legislation recently passed in the Duma is targeting blogs and social media.

4) …and independent media continues to struggle

Only one in seven people in the world live in countries with free press. In many parts of the world, mainstream media is either under tight control by the government itself or headed up media moguls with links to those in power, with dissenting voices within news organisation often being pushed out. Brazil, for instance, has been labelled “the country of 30 Berlusconis” because regional media is “weakened by their subordination to the centres of power in the country’s individual states”. At the start of the year, RIA Novosti — known for on occasion challenging Russian authorities — was liquidated and replaced by the more Kremlin-friendly Rossiya Segodnya (Russia Today), while in Montenegro, has seen efforts by the government to cut funding to critical media. This is not even mentioning countries like North Korea and Uzbekistan, languishing near the bottom of press freedom ratings, where independent journalism is all but non-existent.

5) Attacks on journalists often go unpunished

A staggering fact about the attacks on journalists around the world, is how many happen with impunity. Since 1992, 600 journalists have been killed. Most of the perpetrators of those crimes have not been brought to justice. Attacks can be orchestrated by authorities or by non-state actors, but the lack of adequate responses by those in power “fuels the cycle of violence against news providers,” says RSF. In Mexico, a country notorious for violence against the press, three journalists were murdered in 2013. By last October, the state public prosecutor’s office had yet to announce any progress in the cases of Daniel Martínez Bazaldúa, Mario Ricardo Chávez Jorge and Alberto López Bello, or disclose whether they are linked to their work. Pakistan is also an increasingly dangerous place to work as a journalist. Twenty seven of the 28 journalists killed in the past 11 years in connection with their work have been killed with impunity. Syria, with its ongoing, devastating war, is the deadliest place in the world to be a journalist, while some of the attacks on press during the conflict in Ukraine, have also taken place without perpetrators being held accountable. That attacks in the country appear to be accelerating, CPJ say is “a direct result of the impunity with which previous attacks have taken place”.

This article was published on May 2, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

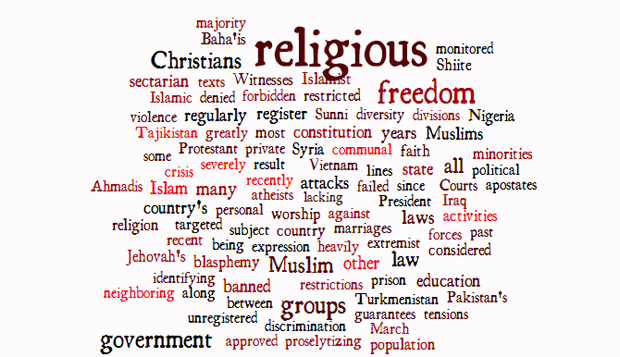

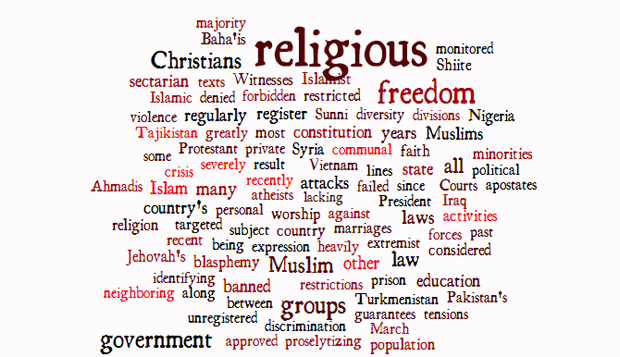

30 Apr 2014 | Egypt, Iraq, News and features, Nigeria, Pakistan, Religion and Culture, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam

In January, Index summarised the U.S. State Department’s “Countries of Particular Concern” — those that severely violate religious freedom rights within their borders. This list has remained static since 2006 and includes Burma, China, Eritrea, Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Uzbekistan. These countries not only suppress religious expression, they systematically torture and detain people who cross political and social red lines around faith.

Today the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), an independent watchdog panel created by Congress to review international religious freedom conditions, released its 15th annual report recommending that the State Department double its list of worst offenders to include Egypt, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam and Syria.

Here’s a roundup of the systematic, ongoing and egregious religious freedom violations unfolding in each.

1. Egypt

The promise of religious freedom that came with a revised constitution and ousted Islamist president last year has yet to transpire. An increasing number of dissident Sunnis, Coptic Christians, Shiite Muslims, atheists and other religious minorities are being arrested for “ridiculing or insulting heavenly religions or inciting sectarian strife” under the country’s blasphemy law. Attacks against these groups are seldom investigated. Freedom of belief is theoretically “absolute” in the new constitution approved in January, but only for Muslims, Christians and Jews. Baha’is are considered apostates, denied state identity cards and banned from engaging in public religious activities, as are Jehovah’s Witnesses. Egyptian courts sentenced 529 Islamist supporters to death in March and another 683 in April, though most of the March sentences have been commuted to life in prison. Courts also recently upheld the five-year prison sentence of writer Karam Saber, who allegedly committed blasphemy in his work.

2. Iraq

Iraq’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but the government has largely failed to prevent religiously-motivated sectarian attacks. About two-thirds of Iraqi residents identify as Shiite and one-third as Sunni. Christians, Yezidis, Sabean-Mandaeans and other faith groups are dwindling as these minorities and atheists flee the country amid discrimination, persecution and fear. Baha’is, long considered apostates, are banned, as are followers of Wahhabism. Sunni-Shia tensions have been exacerbated recently by the crisis in neighboring Syria and extremist attacks against religious pilgrims on religious holidays. A proposed personal status law favoring Shiism is expected to deepen divisions if passed and has been heavily criticized for allowing girls to marry as young as nine.

3. Nigeria

Nigeria is roughly divided north-south between Islam and Christianity with a sprinkling of indigenous faiths throughout. Sectarian tensions along these geographic lines are further complicated by ethnic, political and economic divisions. Laws in Nigeria protect religious freedom, but rule of law is severely lacking. As a result, the government has failed to stop Islamist group Boko Haram from terrorizing and methodically slaughtering Christians and Muslim critics. An estimated 16,000 people have been killed and many houses of worship destroyed in the past 15 years as a result of violence between Christians and Muslims. The vast majority of these crimes have gone unpunished. Christians in Muslim-majority northern states regularly complain of discrimination in the spheres of education, employment, land ownership and media.

4. Pakistan

Pakistan’s record on religious freedom is dismal. Harsh anti-blasphemy laws are regularly evoked to settle personal and communal scores. Although no one has been executed for blasphemy in the past 25 years, dozens charged with the crime have fallen victim to vigilantism with impunity. Violent extremists from among Pakistan’s Taliban and Sunni Muslim majority regularly target the country’s many religious minorities, which include Shiites, Sufis, Christians, Hindus, Zoroastrians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Baha’is. Ahmadis are considered heretics and are prevented from identifying as Muslim, as the case of British Ahmadi Masud Ahmad made all too clear in recent months. Ahmadis are politically disenfranchised and Hindu marriages are not state-recognized. Laws must be consistent with Islam, the state religion, and freedom of expression is constitutionally “subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam,” fostering a culture of self-censorship.

5. Tajikistan

Religious freedom has rapidly deteriorated since Tajikistan’s 2009 religion law severely curtailed free exercise. Muslims, who represent 90 percent of the population, are heavily monitored and restricted in terms of education, dress, pilgrimage participation, imam selection and sermon content. All religious groups must register with the government. Proselytizing and private religious education are forbidden, minors are banned from participating in most religious activities and Muslim women face many restrictions on communal worship. Jehovah’s Witnesses have been banned from the country since 2007 for their conscientious objection to military service, as have several other religious groups. Hundreds of unregistered mosques have been closed in recent years, and “inappropriate” religious texts are regularly confiscated.

6. Turkmenistan

The religious freedom situation in Turkmenistan is similar to that of Tajikistan but worse due to the country’s extraordinary political isolation and government repression. Turkmenistan’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but many laws, most notably the 2003 religion law, contradict these provisions. All religious organizations must register with the government and remain subject to raids and harassment even if approved. Shiite Muslim groups, Protestant groups and Jehovah’s Witnesses have all had their registration applications denied in recent years. Private worship is forbidden and foreign travel for pilgrimages and religious education are greatly restricted. The government hires and fires clergy, censors religious texts, and fines and imprisons believers for their convictions.

7. Vietnam

Vietnam’s government uses vague national security laws to suppress religious freedom and freedom of expression as a means of maintaining its authority and control. A 2005 decree warns that “abuse” of religious freedom “to undermine the country’s peace, independence, and unity” is illegal and that religious activities must not “negatively affect the cultural traditions of the nation.” Religious diversity is high in Vietnam, with half the population claiming some form of Buddhism and the rest identifying as Catholic, Hoa Hao, Cao Dai, Protestant, Muslim or with other small faith and non-religious communities. Religious groups that register with the government are allowed to grow but are closely monitored by specialized police forces, who employ violence and intimidation to repress unregistered groups.

8. Syria

The ongoing Syrian crisis is now being fought along sectarian lines, greatly diminishing religious freedom in the country. President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, aligned with Hezbollah and Shabiha, have targeted Syria’s majority-Sunni Muslim population with religiously-divisive rhetoric and attacks. Extremist groups on the other side, including al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), have targeted Christians and Alawites in their fight for an Islamic state devoid of religious tolerance or diversity. Many Syrians choose their allegiances based on their families’ faith in order to survive. It’s important to note that all human rights, not just religious freedom, are suffering in Syria and in neighboring refugee camps. In quieter times, proselytizing, conversion from Islam and some interfaith marriages are restricted, and all religious groups must officially register with the government.

This article was originally posted on April 30, 2014 at Religion News Service

24 Apr 2014 | Lebanon, News and features, Religion and Culture, Young Writers / Artists Programme

Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, is the lead singer of Mashrou’ Leila

While walking the streets of the upscale downtown district of Beirut, or sipping cocktails in one of El-Hamra’s bustling bars, one could easily forget that Lebanon is a country where civil liberties are still in debate.

Article 534 of the Lebanese penal code states: “Any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature is punished by imprisonment for up to one year.” The vaguely worded article has and is still being used to crackdown on the LGBT community in Lebanon. Compared to its neighbours in the Middle East, Lebanon has long been considered one of the least conservative countries in the region. According to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2013, 18% of the Lebanese population thinks that homosexuality should be accepted in the society, putting it way ahead of Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia where almost 97% of the population views homosexuality as deviant and unnatural.

The Lebanese Psychiatric Society issued a statement in early 2013 saying that: “The assumption that homosexuality is a result of disturbances in the family dynamic or unbalanced psychological development is based on wrong information” — making Lebanon the first Arab country to dismiss the belief that homosexuality is a mental disorder. On 28 January 2014, Judge Naji El Dahdah of Jdeideh Court in Beirut dismissed a claim against a transgender woman accused of having a same-sex relationship with a man, stating that a person’s gender should not simply be based on their personal status registry document, but also on their outward physical appearance and self-perception. The ruling relied on a 2009 landmark decision by Judge Mounir Suleimanfrom the Batroun Court that consenual relations can not be deemed unnatural. “Man is part of nature and is one of its elements, so it cannot be said that any one of his practices or any one of his behaviours goes against nature, even if it is criminal behaviour, because it is nature’s ruling,” stated Suleiman.

Despite the recent positives, being gay in Lebanon is still a taboo. In a country drenched in sectarianism, debates about homosexuality are easily dismissed in the name of religion and homosexuals are accused of promoting debauchery.

“People in Lebanon, and across the region, still act like homosexuality doesn’t exist in our society,” said Kareem, who requested that Index only use his first name. “I think it’s important that we start the conversation and get the issues out in the open, so people can start acknowledging it and then decide their stance on. The fight for our rights comes later on,” he added.

In 2013, Antoine Chakhtoura, mayor of the Beirut suburb of Dekwaneh, ordered security forces to raid and shut-down Ghost, a gay-friendly nightclub. “We fought battles and defended our land and honor, not to have people come here and engage in such practices in my municipality,” the mayor asserted.

Four people were arrested during the raid and brought back to municipal headquarters where they were subject to both physical and verbal harassment: forced to undress, enact intimate acts which included kissing, as well as being violently beaten. Marwan Cherbel, minister of interior at the time of the incident, backed the mayor’s actions, adding that: “Lebanon is opposed to homosexuality, and according to Lebanese law it is a criminal offence.”

Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. In a similar raid on a movie theatre in the municipality of Burj Hammoud known to cater for a gay clientele, 36 men were arrested and forced to undergo the now abolished anal probes — known as tests of shame. The raid came only a few months after Lebanese TV host Joe Maalouf dedicated an episode of his show Enta Horr (You’re Free) to exposing a porn cinema in Tripoli where it was claimed that young boys were being sexually abused by older men.

“The fact that these incidents received a lot of media coverage, some of which denounced the raids, is a sign that the public is little by little taking an interest in the issue of gay rights,” said Kareem. “Five or six years ago, this could have easily gone unnoticed. While the gay community might not be fully accepted or tolerated in Lebanon, it has been gaining a lot more visibility in recent years.”

Helem, a Beirut-based NGO, was established in 2004 to be the first organisation in the Middle East and Arab world to advocate for LGBT rights. In addition to campaigning for the repeal of Article 543, Helem offers a number of services, including legal and medical support to members of the LGBT community. Organisations like Helem and its offshoot Meem, a support group for lesbian women, had a huge impact on raising awareness and correcting misconceptions about homosexuality. Support from Lebanese public figures has also been on the rise in recent years. For example, popular TV host Paula Yacoubian and pop star Elissa have both shown support for the LGBT community in Lebanon via their Twitter accounts.

While the struggle to change the law continues, young artists have been challenging social norms through art. Mashrou’ Leila, a Beirut-based indie rock band, has sparked a lot of controversy thanks to their songs, in which they unapologetically sing about sex, politics, religion and homosexuality in Lebanon. In Shim el Yasmine, the band’s lead singer, Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, sings about an old love, a man whom he wanted to introduce to his family and be his housewife. Director and art critic, Roy Dib, recently won the Teddy Award for best short film in 2014 at the 64th Berlinale International Film Festival with his film Mondial 2010. The film tells the story of a gay Lebanese couple on the road to a holiday weekend in Ramallah, Palestine. It tries to explore the boundaries that make it impossible for a Lebanese person to go into Palestine, as well as the challenges faced by a homosexual couple in the region.

The battle for gay rights in Lebanon is multilayered, and while change is starting to feel tangible, there is still a lot to be done.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org