15 Oct 2014 | Press Releases, Uncategorized

- Awards honour journalists, campaigners and artists fighting censorship globally

- Judges include journalist Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Sir Keir Starmer

- Nominate at www.indexoncensorship.org/nominations

Beginning today, nominations for the annual Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 2015 are open. Now in their 15th year, the awards have honoured some of the world’s most remarkable free expression heroes – from Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim to Syrian cartoonist Ali Farzat to education activist Malala Yousafzai.

The awards shine a spotlight on individuals fighting to speak out in the most dangerous and difficult of conditions. As Idrak Abbasov, 2012 award winner, said: “In Azerbaijan, telling the truth can cost a journalist their life… For the sake of this right we accept that our lives are in danger, as are the lives of our families. But the goal is worth it, since the right to truth is worth more than a life without truth.” Pakistani internet rights campaigner Shahzad Ahmad, a 2014 award winner, said the awards “illustrate to our government and our fellow citizens that the world is watching”.

Index invites the public, NGOs, and media organisations to nominate anyone they believe deserves to be part of this impressive peer group: a hall of fame of those who are at the forefront of tackling censorship. There are four categories of award: Campaigner (sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers); Digital Activism (sponsored by Google); Journalism (sponsored by The Guardian), and the Arts. Nominations can be made online via http://www.indexoncensorship.org/nominations

Winners will be flown to London for the ceremony, which takes place at The Barbican on March 18 2015. In addition, to mark the 15th anniversary of the Freedom of Expression awards, Index is inaugurating an Awards Fellowship to extend the benefits of the award. The fellowship will be open to all winners and will offer training and support to amplify their work for free expression. Fellows will become part of a world-class network of campaigners, activists and artists sharing best practice on tackling censorship threats internationally.

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index, said: “The Index Freedom of Expression Awards is a chance for those whom others try to silence to have their voices heard. I encourage everyone, no matter where they are in the world, to nominate a free expression hero.”

The 2015 awards shortlist will be announced on January 27th 2015. Judges include journalist Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Sir Keir Starmer. The public will be asked to participate in selecting the winner of the Google Digital Activism award through a public vote beginning January 27th 2015. Sir Keir said: “Freedom of expression is part of the bedrock of civilised, democratic society. The Index on Censorship Awards have a material influence on promoting such freedom and both celebrating and protecting those who fight against censorship worldwide. That’s why Doughty Street Chambers chooses Index as its principal charity.”

For more information please contact David Heinemann: [email protected]

_______________________________________________________________________

NOTES FOR EDITORS

About Index on Censorship:

Index on Censorship is an international organisation that promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression. The inspiration of poet Stephen Spender, Index was founded in 1972 to publish the untold stories of dissidents behind the Iron Curtain and beyond. Today, we fight for free speech around the world, challenging censorship whenever and wherever it occurs. Index believes that free expression is the foundation of a free society and endorses Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.”

About The Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards:

The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise those deemed to be making the greatest impact in tackling censorship in their chosen area.

Awards categories:

Journalism – for impactful, original, unwavering journalism across all media (sponsored by The Guardian).

Campaigner – for campaigners and activists who have fought censorship and who challenge political repression (sponsored by Doughty St Chambers).

Digital Activism – for innovative uses of new technology to circumvent censorship and foster debate (sponsored by Google).

Arts – for artists and producers whose work asserts artistic freedom and battles repression and injustice.

Previous award winners include:

Journalism: Azadliq (Azerbaijan), Kostas Vaxevanis (Greece), Idrak Abbasov (Azerbaijan), Ibrahim Eissa (Egypt), Radio La Voz (Peru), Sunday Leader (Sri Lanka), Arat Dink (Turkey), Kareen Amer (Egypt), Sihem Bensedrine (Tunisia), Sumi Khan (Bangladesh), Fergal Keane (Ireland), Anna Politkovskaya (Russia), Mashallah Shamsolvaezin (Iran)

Digital/New Media: Bassel Khartabil (Palestine/Syria), Freedom Fone (Zimbabwe), Nawaat (Tunisia), Twitter (USA), Psiphon (Canada), Centre4ConstitutionalRights (US), Wikileaks

Advocacy: Malala Yousafzai (Pakistan), Nabeel Rajab (Bahrain), Gao Zhisheng (China), Heather Brooke (UK), Malik Imtiaz Sarwar (Malaysia), U.Gambira (Burma), Siphiwe Hlope (Swaziland), Beatrice Mtetwa (Zimbabwe), Hashem Aghajari (Iran)

Arts: Zanele Muholi (South Africa), Ali Farzat (Syria), MF Husain (India), Yael Lerer/Andalus Publishing House (Israel), Sanar Yurdatapan (Turkey)

You have received this email because email address ‘[email protected]’ is subscribed to ‘AWARDS 2015 Call For Nominations’.

14 Oct 2014 | Awards, News and features

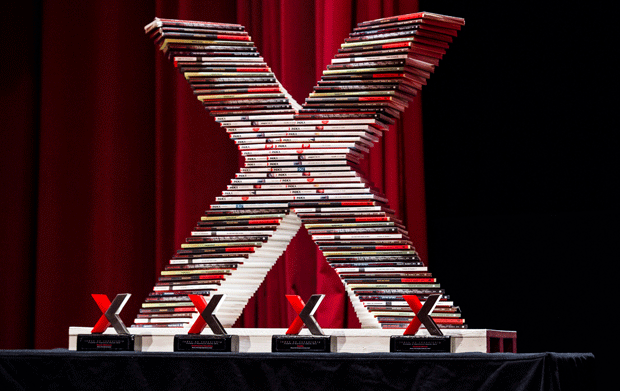

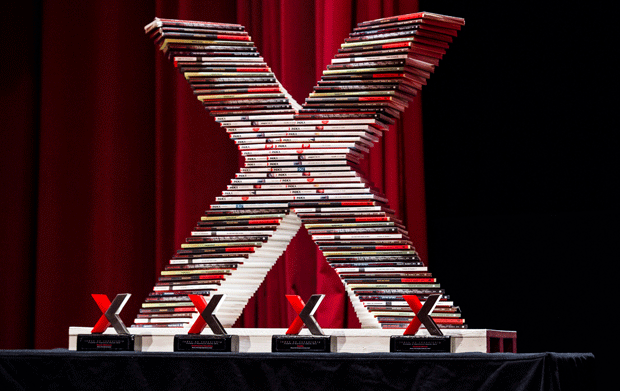

(Photo: Alex Brenner / Index on Censorship)

Nominations for the annual Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 2015 are open. Now in their 15th year, the awards have honoured some of the world’s most remarkable free expression heroes – from Russian investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya to education activist and 2014 Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai.

The awards shine a spotlight on individuals fighting to speak out in the most dangerous and difficult of conditions. As Idrak Abbasov, 2012 award winner, said: “In Azerbaijan, telling the truth can cost a journalist their life… For the sake of this right we accept that our lives are in danger, as are the lives of our families. But the goal is worth it, since the right to truth is worth more than a life without truth.” Pakistani internet rights campaigner Shahzad Ahmad, a 2014 award winner, said the awards “illustrate to our government and our fellow citizens that the world is watching”.

Index invites the public, NGOs, and media organisations to nominate anyone they believe deserves to be part of this impressive peer group. There are four categories of award: Campaigner (sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers); Digital Activism (sponsored by Google); Journalism (sponsored by The Guardian), and the Arts. Nominations can be made online and are open until November 20, 2014.

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index, said: “The Index Freedom of Expression Awards is a chance for those whom others try to silence to have their voices heard. I encourage everyone, no matter where they are in the world, to nominate a free expression hero.”

Winners will be flown to London for the ceremony, which takes place at The Barbican on March 18 2015, and which will feature music and entertainment from across the globe.

In addition, to mark the 15th anniversary of the Freedom of Expression awards, Index is inaugurating an Awards Fellowship to extend the benefits of the award. The fellowship will be open to all winners and will offer training and support to amplify their work for free expression. Fellows will become part of a world-class network of campaigners, activists and artists sharing best practice on tackling censorship threats internationally. The fellowship will be launched formally later in the year.

Determination to tell the truth

Judges for this year’s Freedom of Expression awards include journalist Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Sir Keir Starmer. Sir Keir said: “Freedom of expression is part of the bedrock of civilised, democratic society. The Index on Censorship awards have a material influence on promoting such freedom and both celebrating and protecting those who fight against censorship worldwide. That’s why Doughty Street Chambers chooses Index as its principal charity.”

Alan Rusbridger, editor-in-chief, Guardian News & Media said: “We’re proud to once again be sponsoring the Journalism category of the Freedom of Expression Awards. Previous winners of this category have demonstrated dogged determination to tell the truth, and at a time when journalistic freedom is under pressure like never before, this category holds even greater significance.”

The Digital Activism Award will, for the second year running, be chosen by public vote. Google’s Head of Free Expression, Europe, William Echikson said: “Our support of the Index awards reflects our common concerns about the ongoing and increasing government crackdown against the free and open internet. When we first learned about the Digital Activism Award, we were immediately impressed with its motto, which celebrates the fundamental right to ‘write, blog, tweet, speak out, protest and create art and literature and music.’”

Index on Censorship is delighted also to have the continued support of academic and professional publishers, SAGE, for this year’s awards. Ziyad Marar, Global Publishing Director of SAGE, which sponsors the awards, said: “Through working with Index for many years both as publisher of the magazine and sponsors of the awards ceremony we are proud to support a truly outstanding organization as they defend free expression around the world.”

This article was posted on 14 Oct, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Oct 2014

5 awards. 16 years. Champions against censorship.

The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise those individuals and groups making the greatest impact in tackling censorship worldwide. Established 16 years ago, the awards shine a light on work being undertaken in defence of free expression globally. All too often these stories go unnoticed or are ignored by the mainstream press.

Each year, the awards call attention to some of the bravest journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders in the world. The 2015 awards were no exception. We honoured Amran Abdundi, a Kenyan activist who has worked through various channels to support women who are vulnerable to rape, female circumcision and murder in northeastern Kenya. We also gave awards to Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, a Moroccan rapper who continues to make music about endemic corruption and widespread poverty in his country despite censorship being imprisoned three times; Tamás Bodoky, a journalist campaigning for a free press in Hungary; Rafael Marques de Morais, who has exposed government and industry corruption in Angola; and Safa Al Ahmad, a journalist who has spent three years covertly filming a mass uprising in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province that had, until her film, gone largely unreported.

The Freedom of Expression Awards grew naturally from the principles established by our founder, the poet Stephen Spender, who sought to give a voice to those facing censorship behind the Iron Curtain and beyond. Index had long championed writers and artists fighting threats to free expression by publishing their work in our magazine, or through our own reporting. Recognising their work through our Freedom of Expression Awards was a natural next step.

In Azerbaijan, where I have come from, telling the truth can cost a journalist their life.

That is the price that my colleagues in Azerbaijan are paying for the right of the Azerbaijani people to know the truth about what is happening in their country.

For the sake of this right we accept that our lives are in danger, as are the lives of our families.

But the goal is worth it, since the right to truth is worth more than a life without truth.”

— Idrak Abbasov, Award winner, 2012

Who is eligible

Anyone involved in tackling free expression threats – either through journalism, advocacy, arts or using digital techniques – is eligible for the awards. Index invites nominations from the public via its website and through social media platforms. Other non-governmental organisations are also invited to suggest nominees, and individuals and groups can also self-nominate. There is no cost to applying.

We shortlist on the basis of those who are deemed to be making the greatest impact in tackling censorship in their chosen area, with a particular focus on those who are tackling topics that are little covered or tackled by others, or who are using innovative methods to fight censorship.

Nominations are now closed. The shortlist will be announced on 27 January 2015.

The categories?

Advocacy – recognises campaigners and activists who have fought censorship and challenge political repression. This award is sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers.

Arts – recognises artists and producers whose work asserts artistic freedom and battles repression and injustice.

Digital Activism – recognises innovative uses of new technology to circumvent censorship and foster debate. This award is sponsored by Google.

Journalism – for impactful, original, unwavering investigative journalism across all media. This award is sponsored by The Guardian.

The judges

Each year Index recruits an independent panel of judges with expertise in advocacy, arts, journalism and human rights to work on the shortlisting of nominees. This year’s judges include journalist and campaigner Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Keir Starmer. Previous judges include playwright Howard Brenton, philanthropist Sigrid Rausing, and broadcaster Samira Ahmed.

The timeline

Nominations opened on October 14 and remained open until November 20, 2014. Nominations are now closed. The nominee shortlist will be announced on January 27. Judges make their final awards selection in February. The Digital Advocacy winner is decided by public vote. The winners of the awards will be announced at the 2015 Index Freedom of Expression Awards on March 18.

26 Sep 2014 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Politics and Society

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

“States must stop trying to define who is and isn’t a journalist. The media landscape has changed irreversibly,” said Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, as she opened the organisation’s Open Journalism event in Vienna on Friday, 19 Sept.

Journalism – wherever you draw its boundaries – has more voices than ever, but are all they all being properly recognised and safeguarded? This was one of the main problems addressed by the expert panel, which included Index on Censorship, alongside delegates from Azerbaijan, Serbia, Estonia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Bosnia and many other OSCE member states.

Gill Phillips, the Guardian’s director of editorial legal services, spoke via pre-recorded video about difficulties in defining journalism and deciding who gets journalistic protection. She cited the Snowden scoop, which was led by Glenn Greenwald, a former lawyer, and later embroiled his partner, David Miranda. Who gets the protection? Greenwald? Miranda? Lead staff reporter David Leigh? All three?

There was widespread condemnation of Russia’s new law, which compels bloggers with more than 3,000 views per day to be registered with the authorities. “[The bloggers] have certain privileges and obligations,” said Irina Levova, from the Russian Association of Electronic Communications, who repeatedly defended the law. “Online and offline rights are not the same,” she said, adding that some of those who deemed the law a mode of censorship have been revealed as “foreign agents”.

Another topic – raised repeatedly by various attendees – was Russian media’s growing influence over citizens in nearby countries. Begaim Usenova of the Media Policy Institute in Kyrgyzstan said: “The common view being spread from the Russian media is that the United States is starting world war three and only Putin can stop him.”

Yaman Akdeniz, a Turkish cyber-rights activist, shared news of Twitter accounts that remain blocked in his country, including some with over 500,000 followers. Igor Loskutov, a business director from Kazakhstan, looked back on the first 20 years of internet in his country and how authorities have gone from ignoring their first rudimentary websites to now wanting complete control.

The thorny issue of “public interest” was also discussed. Jose Alberto Azeredo Lopes, professor of International Law at the Catholic University of Porto, raised some smiles with his theory: “It’s like pornography. You can’t define it. But you know it when you see it.”

As the day-long discussions wrapped up, one delegate asked: if a blogger’s first-ever post goes viral, are they immediately subject to the same laws as the press? Especially in countries that now insist bloggers register.

The debate over the difference between journalists and bloggers went round in circles – as it always does – but the OSCE is hoping to be able to compile all the findings from its expert meetings into an online resource to move the discussion forward.

Azeredo Lopes concluded: “If you don’t distinguish freedom of expression from freedom of the press, you end up with no journalists, and that is the crisis that journalism faces today.”

Read our interview with Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE’s Representative on Freedom of the Media, in the autumn issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, coming soon

This article was published on Friday September 26 at indexoncensorship.org