4 Apr 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases

World leaders must commit to keeping invasive surveillance systems and technologies out of the hands of dictators and oppressive regimes, said a new global coalition of human rights organizations as it launched today in Brussels.

The Coalition Against Unlawful Surveillance Exports (CAUSE) – which includes Amnesty International, Digitale Gesellschaft, FIDH, Human Rights Watch, the New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute, Privacy International, Reporters without Borders and Index on Censorship – aims to hold governments and private companies accountable for abuses linked to the US$5 billion and growing international trade in communication surveillance technologies. Governments are increasingly using spying software, equipment, and related tools to violate the right to privacy and a host of other human rights.

“These technologies enable regimes to crush dissent or criticism, chill free speech and destroy fundamental rights. The CAUSE coalition has documented cases where communication surveillance technologies have been used, not only to spy on people’s private lives, but also to assist governments to imprison and torture their critics,” said Ara Marcen Naval at Amnesty International.

“Through a growing body of evidence it’s clear to see how widely these surveillance technologies are used by repressive regimes to ride roughshod over individuals’ rights. The unchecked development, sale and export of these technologies is not justifiable. Governments must swiftly take action to prevent these technologies spreading into dangerous hands” said Kenneth Page at Privacy International.

In an open letter published today on the CAUSE website, the groups express alarm at the virtually unregulated global trade in communications surveillance equipment.

The website details the various communication surveillance technologies that have been made and supplied by private companies and also highlights the countries where these companies are based. It shows these technologies have been found in a range of countries such as Bahrain, Brazil, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, Nigeria, Morocco, Turkmenistan, UAE, and many more.

“Nobody is immune to the danger communication surveillance technologies poses to individual privacy and a host of other human rights. And those who watch today, will be watched tomorrow” sadi Karim Lahidji, FIDH President. “The CAUSE has been created to call for responsible regulation of the trade and to put an end to the abuses it enables” he added.

Although a number of governments are now beginning to discuss how to restrict this trade, concerns remain. Without sustained international pressure on governments to establish robust comprehensive controls on the trade based on international human rights standards, the burgeoning proliferation of this intrusive technology will continue – fuelling even further abuses.

“There is a unique opportunity for governments to address this problem now and to update their regulations to align with technological developments” said Tim Maurer at New America’s Open Technology Institute.

“More and more journalists, netizens and dissidents are ending up in prison after their online communications are intercepted. The adoption of a legal framework that protects online freedoms is essential, both as regards the overall issue of Internet surveillance and the particular problem of firms that export surveillance products,” said Grégoire Pouget at Reporters Without Borders.

“We have seen the devastating impact these technologies have on the lives of individuals and the functioning of civil society groups. Inaction will further embolden blatantly irresponsible surveillance traders and security agencies, thus normalizing arbitrary state surveillance. We urge governments to come together and take responsible action fast,” said Wenzel Michalski at Human Rights Watch.

The technologies include malware that allows surreptitious data extraction from personal devices; tools that are used to intercept telecommunications traffic; spygear used to geolocate mobile phones; monitoring centres that allow authorities to track entire populations; anonymous listening and camera spying on computers and mobile phones; and devices used to tap undersea fibre optic cables to enable mass internet monitoring and filtering.

“As members of the CAUSE coalition, we’re calling on governments to take immediate action to stop the proliferation of this dangerous technology and ensure the trade is effectively controlled and made fully transparent and accountable” said Volker Tripp at Digitale Gesellschaft.

NGOs in CAUSE have researched how such technologies end up in the hands of security agencies with appalling human rights records, where they enable security agents to arbitrarily target journalists, protesters, civil society groups, political opponents and others.

Cases documented by coalition members have included:

• German surveillance technology being used to assist torture in Bahrain;

• Malware made in Italy helping the Moroccan and UAE authorities to clamp down on free speech and imprison critics;

• European companies exporting surveillance software to the government of Turkmenistan, a country notorious for violent repression of dissent.

• Surveillance technologies used internally in Ethiopia as well as to target the Ethiopian diaspora in Europe and the United States.

28 Mar 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

“The media tells you what to think!”

That’s a basic criticism of Western journalism, whether it’s of the “CNN controls your mind” or “Left Liberal Elites have monopolised the agenda” variety. Most people reject this, rightly, as a straw-man. We pride ourselves on our ability to sift information, reject weak arguments and come to our own points of view.

A more worrying criticism is that the news directs what you think about. Decisions to give Story X prominence and headlines, and to bury or spike Story Y, mean most of us can only encounter X. Newsworthy stories become obscure if drowned out by others or omitted entirely. We’re denied investigation or campaigning on vital issues because nobody knows they exist.

In Britain this is not what we typically mean by ‘censorship’, not the recourse of despots or prudes. Nevertheless, self-censorship with market and readership in mind denies all but the most devout news-addict important stories. And without the news we can’t have comment pieces, columns, Twitter debates and opinion blogs.

Consider the EuroMaidan protests in Kiev through spring. Coverage gave the impression of a pro-EU crowd led by a heavyweight champion, with a worrying fringe of violent nationalists – Svoboda and Right Sector. This followed the ‘mainstream-extremist’ simplification presented in Egypt, Syria and Libya. Other crucial groups were ignored: LGBT activists set up the protest’s hotlines, feminists ran the makeshift hospitals, Afghan war veterans defended them.

The world’s focus on Kiev and Crimea drove other issues from the spotlight. The Syrian civil war has hardly featured recently, but that conflict has far more casualties, worse upheaval and more immediate consequences for Britain. Refugees are currently en route to claim asylum – this is the last we heard. Similarly, the Philippines dominated the winter’s news after Typhoon Haiyan. Now it’s forgotten in favour of flight MH370 despite the catastrophic ongoing humanitarian crisis, again with more lives at stake.

The Arab Spring is itself a good example of one narrative deafening public consciousness. How many of us knew that at the same time as protests ignited Yemen and Syria in July 2011, Malaysia’s government gassed peaceful crowds and arrested 1,400 protesters after tens of thousands marched for electoral reform? It’s tempting to wonder whether greater coverage, and greater international pressure, could have supported the democratic reforms demanded.

Closer to home, consider the brief uproar caused by the 2013 UK policing bill, drafted to outlaw ‘annoyance and nuisance’ and give police arbitrary powers to ban groups from protest areas. Although the drafts were publicly available, and campaign groups voiced outrage swiftly, left-wing papers took notice only after the bill had passed the Commons. The bill was softened, not by popular pressure or national debate, but by a few conscientious Lords.

Readers could forgive the media for prioritising other stories if they are more pressing. When headlines are crowded by non-events, however, this seems a poor excuse. The British news spectrum was recently obsessed with Labour politicians Harriet Harman and Patricia Hewitt, who worked for the National Council for Civil Liberties (now ‘Liberty’) in the 1970s. That council granted affiliate status to the now-banned Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE). The Daily Mail made a huge splash about its PIE investigation in February, despite uncovering no new information. That paper alone had reported the same story in 1983, 2009, 2012 and 2013. Eventually the BBC, online world and print media all covered the controversy, meaning more worthy issues lost precedence.

Madeleine McCann has dominated countless front pages, reporters chewing over the barest scraps of Portuguese police leaks. No real progress has been made for years. Pundits admit the story retains prominence largely because the McCanns are photogenic, and similar stories would have fallen off the agenda. There are hundreds of similar unsolved child disappearances, just from the UK. Drug scares, MMR vaccine hysteria, celeb gossip and royal gaffes (not to mention Diana conspiracies) complete the non-story roster.

If this seems regrettable but harmless, consider sexual violence. Teacher-child abuse, violent assaults and gang attacks deserve coverage, but their sheer news monopoly perpetuates the public’s false idea of ‘real rape’. Most sexual abuse is between couples or acquaintances: campaigners have shown the myth that ‘real rape’ must involve a violent stranger impedes both prosecution and victim support.

There is no silver bullet, just as no one news organisation can really be blamed for censorship by omission. Few people want or need constant updates on upheaval in South Sudan or Somalia – but we could be reminded they’re happening at all. Editors will always reflect on what is vogue, what will sell, and a diverse free press ensures a broad range of stories. Perhaps the rise of online citizen-reporting can bridge the gap. Nevertheless, the danger of noteworthy events falling into obscurity should niggle at the back of the mind – for those who know enough to think about it.

This article was posted on March 28, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Mar 2014 | Awards, News and features

From upper left: Shahzad Ahmad, Rahim Haciyev, Shu Choudhary, Mayam Mahmoud. (Photos: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

This year’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2014 were awarded to a diverse group of remarkable individuals and organisation from the young female Egyptian Rapper to a Pakistani internet campaigner, from an Indian digital pioneer to an Azerbaijani newspaper.

The Freedom of Expression Awards 2014 took place this evening at the Barbican Centre in London and saw 18 year old, Egyptian rapper, Mayam Mahmoud win the Arts Award; Pakistani internet freedom fighter, Shahzad Ahmad pick up the Advocacy Award; Shu Choudhary, the Indian journalist who has created an egalitarian news platform receive the Digital Activism Award; and the Azeri newspaper, Azadliq, win the Journalism Award.

The Freedom of Expression Awards recognise the bravest journalists, artists and activists from around the world. From Edward Snowden to FreeWeibo and David Cecil to Colectivo Chuhcan, their remarkable true stories remind us that the right to free expression must be defended at all costs. Index is proud to bring these voices to London and shine a light on their work for the world to see.

Index Arts award: Mayam Mahmoud, Egyptian Hip-hop Artist

Mayam Mahmoud, Egyptian Hip-hop Artist, accepting her award (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

A finalist on Arab’s Got Talent, hijab wearing Egyptian rapper Mayam Mahmoud uses hip-hop to address issues such as sexual harassment and to stand up for women’s rights in the country that, after the hope of Tahrir Square, is slipping back into authoritarianism.

Google Digital Activism award: Shubhranshu Choudhary, Indian Journalist

Shubhranshu Choudhary at the Index awards (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Shubhranshu Choudhary is the brains behind CGNet Swara, a mobile-phone based news service that allows some of India’s poorest citizens to upload and listen to hyper-local reports in their own dialect, no smartphone required! CGNet Swara is both circumventing India’s strict radio licencing laws and creatively providing an outlet for those overlooked people on the wrong side of the digital divide.

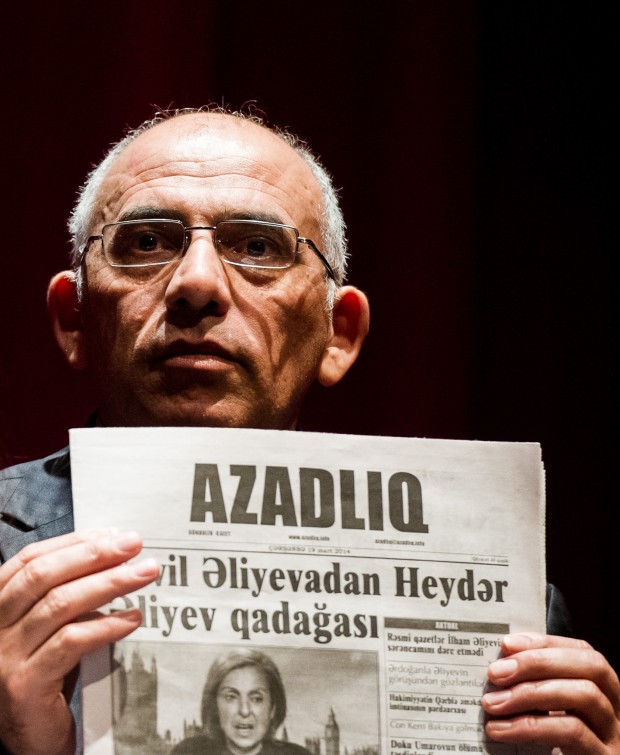

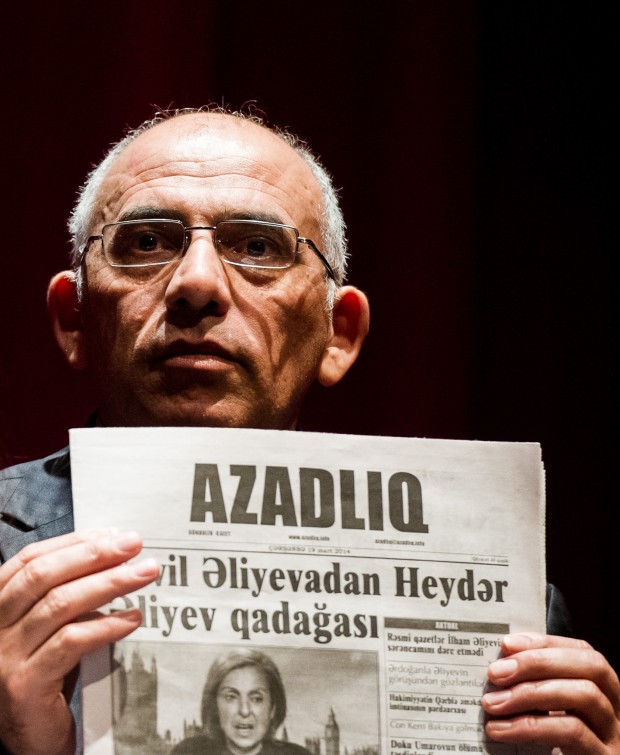

The Guardian Journalism award: Azadliq, Azerbaijani independent Newspaper

Rahim Haciyev, deputy editor-in-chief of Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

One of the last independent media outlets in Azerbaijan, Azadliq has continued to report on government corruption and cronyism in spite of increasing pressures and a financial squeeze enforced by the authorities.

Doughty Street Advocacy award: Shahzad Ahmad, Pakistani Campaigner

Shahzad Ahmad at the Index awards (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Shahzad Ahmad leads the fight against online censorship in Pakistan. He has sued the Pakistani government over their suspected use of surveillance software, FinFisher, and he is suing the government over its ongoing blocking of YouTube which is depriving his people of one of the world’s most popular video channels.

#IndexAwards2014: The Doughty Street Advocacy Award winner Shahzad Ahmad from Index on Censorship on Vimeo.

21 Mar 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Qatar

Freedom of speech clashing with commercial concerns has been an ongoing theme for many media and internet companies operating on an international stage, but it’s rare that a country’s liberal approach to expression is presented, in itself, as a prime investment opportunity.

Now Qatar, the richest country in the world, is positioning itself as a liberal alternative to the other resource-rich Gulf states – as revealed in an op-ed by the CEO of a premier London-listed Qatari investment fund.

The chairman of the Qatar Investment Fund PLC, Nick Wilson, authored an article this week on ArabianBusiness.com, claiming the country “has a habit of pushing its progressive agenda, to the irritation of its more conservative neighbouring states elsewhere in the Gulf Co-operation Council.”

Qatar Investment Fund manages approximately £200m in assets – investing into Qatari equities and employing dozens of fund managers. Its website trumpets Qatar as one of the worlds fastest growing economies, as well as pointing to its hugely lucrative gas exports.

But in this piece, the investment managers emphasised a different aspect of Qatar – the the “liberal minded” Al Jazeera TV network and an apparent commitment to free speech, especially when compared with its Gulf neighbours.

“We’ve seen the consequences of blocking access to information in other countries of the region.”

“Qatar is a bastion of free speech – and the flow of information should help to create a benign environment for investors.” he added.

The piece also pointed towards progressive women’s rights in Qatar, noted the political unpredictability of the region, but concluded that Qatar was “less frightened of change,” and “safe for business.”

As Wilson mentioned, Qatar now faces an unprecedented rift with the other GCC members – in particular Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and UAE who dramatically withdrew their envoys from Doha recently. He noted that Qatar had not withdrawn their envoys in retaliation, suggestive of their “liberal” tendencies.

But Qatar’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood both in Egypt and the Gulf, has set it contrary to GCC security policy – with UAE and Saudi Arabia having designated the Brotherhood “a terrorist organisation.”

And Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a provocative Islamist preacher and key Muslim Brotherhood member, is based in Doha. He presents a weekly show and sermon on the Arabic version of Al Jazeera, reportedly watched by 20 million viewers.

The outspoken preacher recently incensed the UAE by denouncing the Emirates political policies as “un-Islamic,” in response to an Islamist crackdown orchestrated by UAE’s sophisticated state security apparatus.

Qatar, as Wilson noted in his article, has irked its neighbours by allowing al Jazeera, al Qaradawi and the Muslim Brotherhood to be supported by Qatar’s extensive financial resources.

It now faces potential sanctions from Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain has even called for the GCC to be split up – unless Qatar shuts down the al-Jazeera TV network, ejects al-Qaradawi and stops support for Islamists.

While secretive Qatar is keen to maintain its supportive stance of the Brotherhood, it’s unclear whether freedom of expression comes into play or if there are wider geopolitical considerations at play.

More likely it is the latter – analysts reaction to the Qatar Investment Fund’s glowing appraisal of Qatar’s “liberal” values has been muted.

“Qatar may be a freer society than some of it’s neighbours, but this is hardly a useful measure,” says David Wearing, a PhD candidate and Gulf Expert at SOAS University in London.

“Objectively, it is an autocratic monarchy; not liberal, and certainly not democratic. Some space exists in Qatar for criticism of other regional governments, but not of the Doha regime itself.”

Wearing pointed to the case of Mohammed al-Ajami who was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment in October 2013, for “insulting the emir.”

Nader Hassan, a professor at the University of South Alabama, thinks the op-ed may fit into a broader PR narrative which is sanitising Qatar’s human rights reputation.

“Qatar has been playing a very skillful public relations game,” he told Index, “portraying itself as a beacon of free speech and press freedom in the region.”

“Compared to its more powerful neighbor, Saudi Arabia, this may be true. However, there are significant restrictions on press freedom in Qatar.

“Al Jazeera, for example, almost never carries any critical pieces on Qatar, such as the abuse of migrant workers.”

Hassan admitted that some Al Jazeera pieces favoured openness and journalistic professionalism- but concluded that calling the network “liberal” was “far from the truth.”

This article was posted on 21 March 2014 at indexoncensorship.org