19 Jul 2018 | News and features, Volume 46.01 Spring 2017

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1531732086773{background: #ffffff url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FinalBullshit-withBleed.jpg?id=101381) !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Manipulating news and discrediting the media are techniques that have been used for more than a century. Originally published in the spring 2017 issue The Big Squeeze, Index’s global reporting team brief the public on how to watch out for tricks and spot inaccurate coverage. Below, Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley introduces the special feature” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

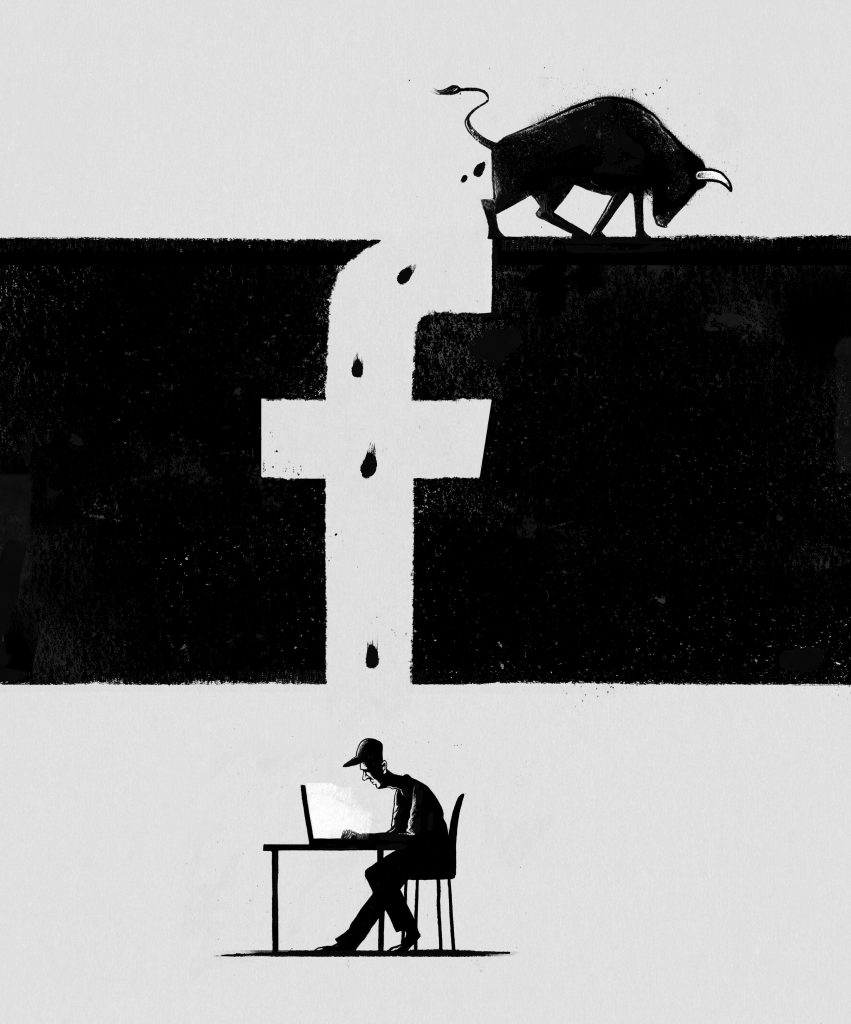

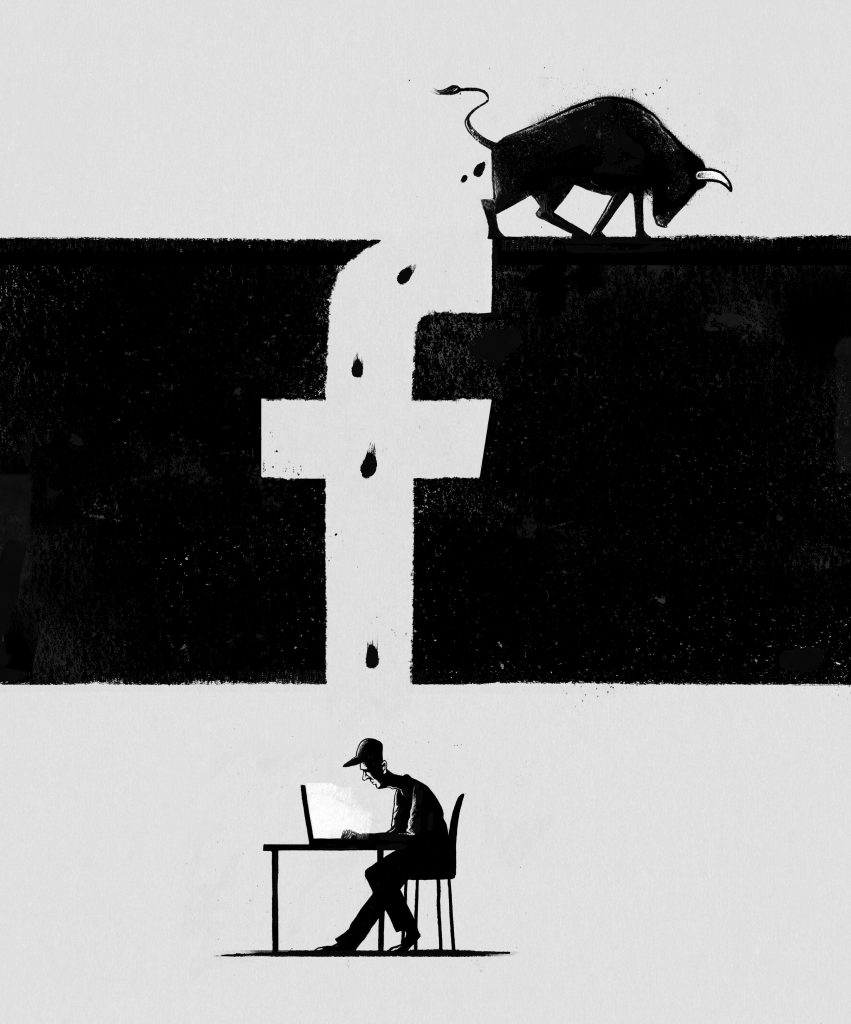

FICTIONAL ANGLES, SPIN, propaganda and attempts to discredit the media, there’s nothing new there. Scroll back to World War I and you’ll find propaganda cartoons satirising both sides who were facing each other in the trenches, and trying to pump up public support for the war effort. If US President Donald Trump is worried about the “unbalanced” satirical approach he is receiving from the comedy show Saturday Night Live, he should know he is following in the footsteps of Napoleon who worried about James Gillray’s caricatures of him as very short, while the vertically challenged French President Nicolas Sarkozy feared the pen of Le Monde’s cartoonist Plantu.

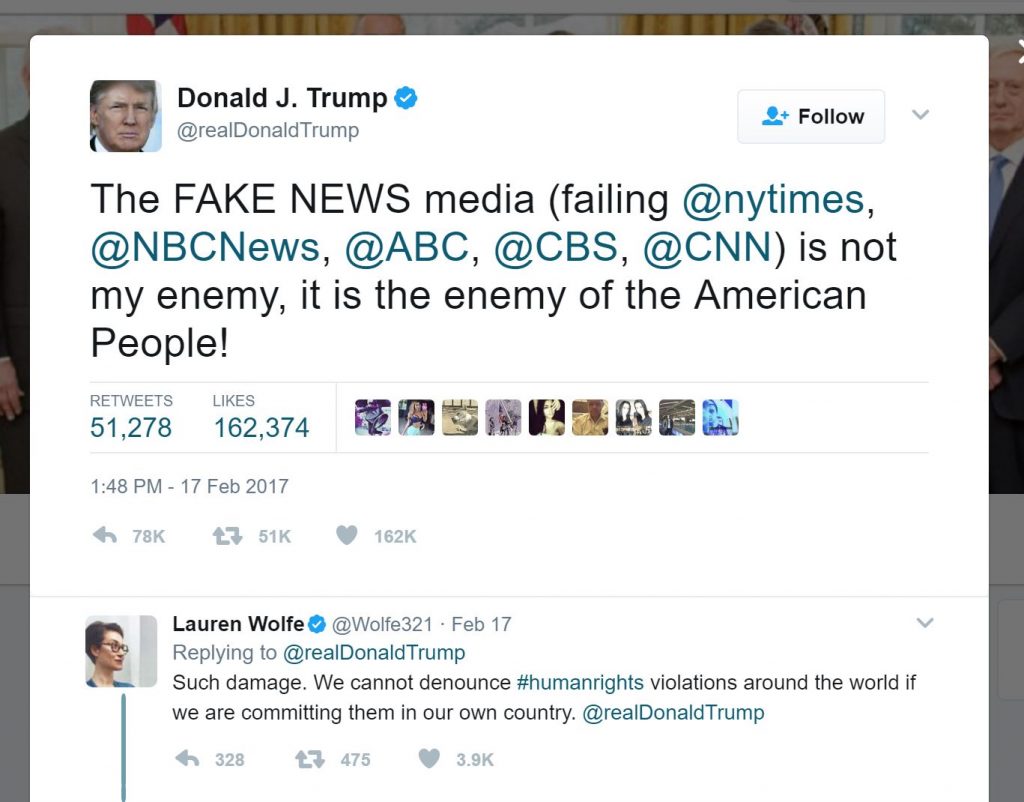

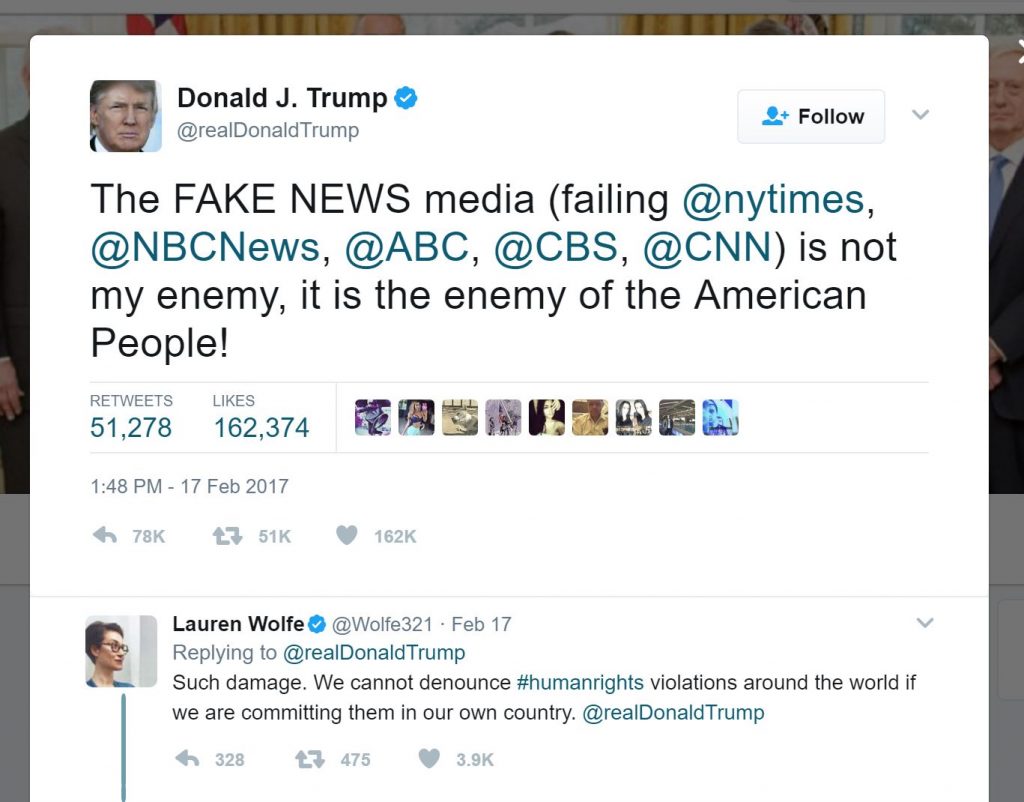

When Trump cries “fake news” at coverage he doesn’t like, he is adopting the tactics of Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa. Cor-rea repeatedly called the media “his greatest enemy” and attacked journalists personally, to secure the media coverage he wanted.

As Piers Robinson, professor of political journalism at Sheffield University, said: “What we have with fake news, distorted information, manipulation communication or propaganda, whatever you want to call it, is nothing new.”

Our approach to it, and the online tools we now have, are newer however, meaning we now have new ways to dig out angles that are spun, include lies or only half the story.

But sadly while the internet has brought us easy access to multitudes of sources, and the ability to watch news globally, it also appears to make us lazier as we glide past hundreds of stories on Twitter, Facebook and the digital world. We rarely stop to analyse why one might be better researched than another, whose journalism might stand up or has the whiff of reality about it.

As hungry consumers of the news we need to dial up our scepticism. Disappointingly, research from Stanford University across 12 US states found millennials were not sceptical about news, and less likely to be able to differentiate between a strong news source and a weak one. The report’s authors were shocked at how unprepared students were in questioning an article’s “facts” or the likely bias of a website.

And, according to Pew Research, 66% of US Facebook users say they use it as a news source, with only around a quarter clicking through on a link to read the whole story. Hardly a basis for making any decision.

At the same time, we are seeing the rise of techniques to target particular demographics with political advertising that looks like journalism. We need to arm ourselves with tools to unpick this new world of information.

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Credit: Ben Jennings

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Turkey

A Picture Sparks a Thousand Stories

KAYA GENÇ dissects the use of shocking images and asks why the Turkish media didn’t check them

Two days after last year’s failed coup attempt in Turkey, one of the leading newspapers in the country, Sozcu, published an article with two shocking images purportedly showing anti-coup protesters cutting the throat of a soldier involved in the coup. “In the early hours of this morning the situation at the Bosphorus Bridge, which had been at the hands of coup plotters until last night, came to an end,” the piece read. “The soldiers handed over their guns and surrendered. Meanwhile, images of one of the soldiers whose throat was cut spread over social media like an avalanche, and those who saw the image of the dead soldier suffered shock,” it said.

These powerful images of a murdered uniformed youth proved influential for both sides of the political divide in Turkey: the ultra-conservative Akit newspaper was positive in its reporting of the lynching, celebrating the killing. The secularist OdaTV, meanwhile, made it clear that it was an appalling event and it was publishing the pictures as a means of protest.

Neither publication credited the images they had published in their extremely popular articles, which is unusual for a respectable publication. A careful reader could easily spot the lack of sources in the pieces too; there was no eyewitness account of the purported killing, nor was anyone interviewed about the event. In fact, the piece was written anonymously.

These signs suggested to the sceptical reader that the news probably came from someone who did not leave their desk to write the story, choosing instead to disseminate images they came across on social media and to not do their due diligence in terms of verifying the facts.

On 17 July, Istanbul’s medical jurisprudence announced that, among the 99 dead bodies delivered to the morgue in Istanbul, there was no beheaded person. The office of Istanbul’s chief prosecutor also denied the news, and it was declared that the news was fake.

A day later, Sozcu ran a lengthy commentary about how it prepared the article. Editors accepted that their article was based on rumours and images spread on social media. Numerous other websites had run the same news, their defence ran, so the responsibility for the fake news rested with all Turkish media. This made sense. Most of the pictures purportedly showing lynched soldiers were said to come from the Syrian civil war, though this too is unverifiable. Major newspapers used them, for different political purposes, to celebrate or condemn the treatment of putschist soldiers.

More worryingly, the story showed how false images can be used by both sides of Turkey’s political divide to manipulate public opinion: sometimes lies can serve both progressives and conservatives.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

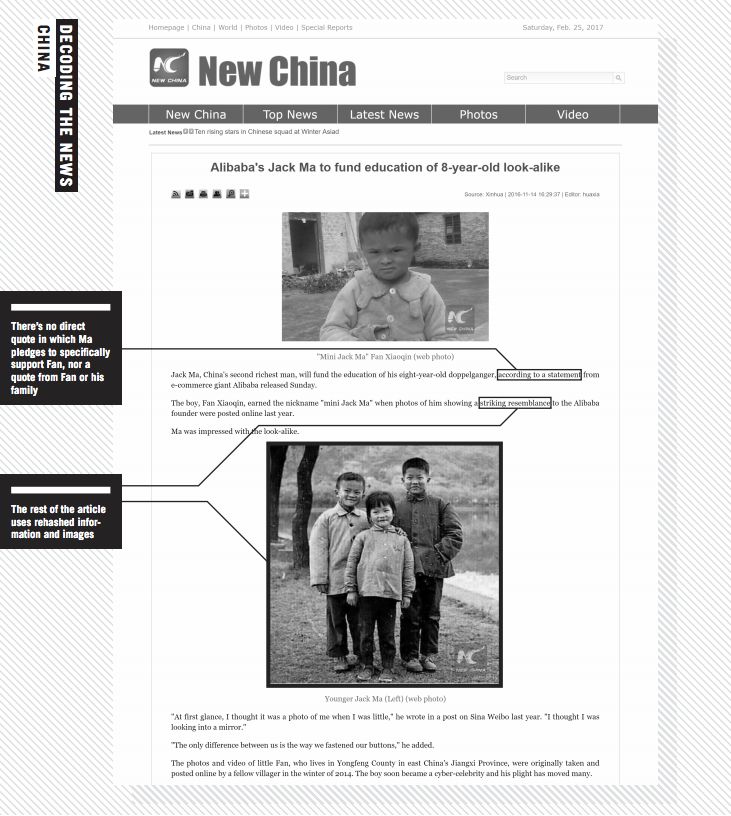

Decoding the News: China

A Case of Mistaken Philanthropy

JEMIMAH STEINFELD writes on the story of Jack Ma’s doppelganger that went too far

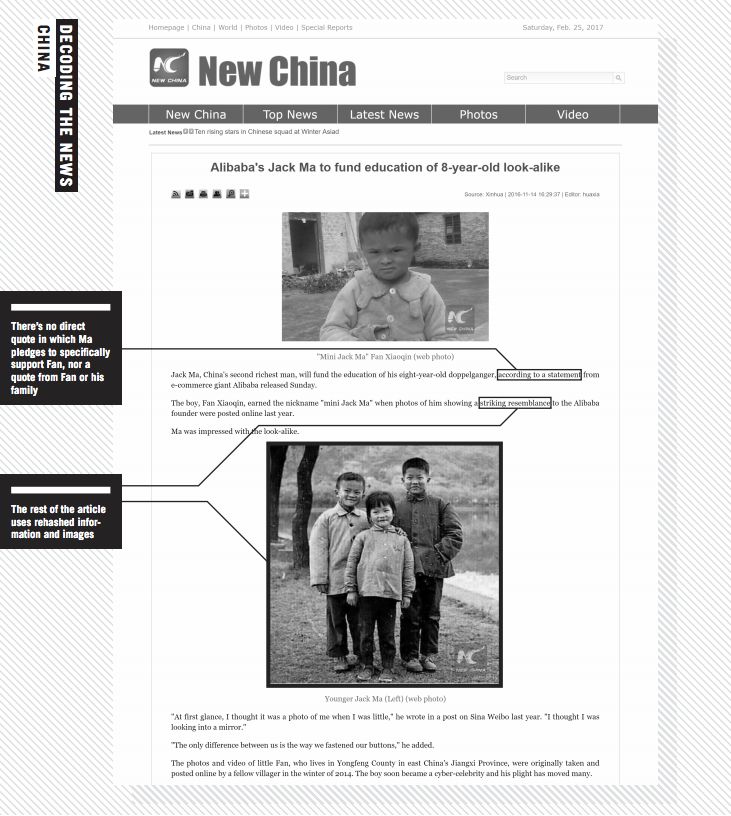

Jack Ma is China’s version of Mark Zuckerberg. The founder and executive chairman of successful e-commerce sites under the Alibaba Group, he’s one of the wealthiest men in China. Articles about him and Alibaba are frequent. It’s within this context that an incorrect story on Ma was taken as verbatim and spread widely.

The story, published in November 2016 across multiple sites at the same time, alleged that Ma would fund the education of eight-year-old Fan Xiaoquin, nicknamed “mini Ma” because of an uncanny resemblance to Ma when he was of a similar age. Fan gained notoriety earlier that year because of this. Then, as people remarked on the resemblance, they also remarked on the boy’s unfavourable circumstances – he was incredibly poor and had ill parents. The story took a twist in November, when media, including mainstream media, reported that Ma had pledged to fund Fan’s education.

Hints that the story was untrue were obvious from the outset. While superficially supporting his lookalike sounds like a nice gesture, it’s a small one for such a wealthy man. People asked why he wouldn’t support more children of a similar background (Fan has a brother, in fact). One person wrote on Weibo: “If the child does not look like Ma, then his tragic life will continue.”

Despite the story drawing criticism along these lines, no one actually questioned the authenticity of the story itself. It wouldn’t have taken long to realise it was baseless. The most obvious sign was the omission of any quote from Ma or from Alibaba Group. Most publications that ran the story listed no quotes at all. One of the few that did was news website New China – sponsored by state-run news agency Xinhua. Even then the quotes did not directly pertain to Ma funding Fan. New China also provided no link to where the comments came from.

Copying the comments into a search engine takes you to the source though – an article on major Chinese news site Sina, which contains a statement from Alibaba. In this statement, Alibaba remark on the poor condition of Fan and say they intend to address education amongst China’s poor. But nowhere do they pledge to directly fund Fan. In fact, the very thing Ma was criticised for – only funding one child instead of many – is what this article pledges not to do.

It was not just the absence of any comments from Ma or his team that was suspicious; it was also the absence of any comments from Fan and his family. Media that ran the story had not confirmed its veracity with Ma or with Fan. Given that few linked to the original statement, it appeared that not many had looked at that either.

In fact, once past the initial claims about Ma funding Fan, most articles on it either end there or rehash information that was published from the initial story about Ma’s doppelganger. As for the images, no new ones were used. These final points alone wouldn’t indicate that the story was fabricated, but they do further highlight the dearth of new information, before getting into the inaccuracy of the story’s lead.

Still, the story continued to spread, until someone from Ma’s press team went on the record and denied the news, or lack thereof.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

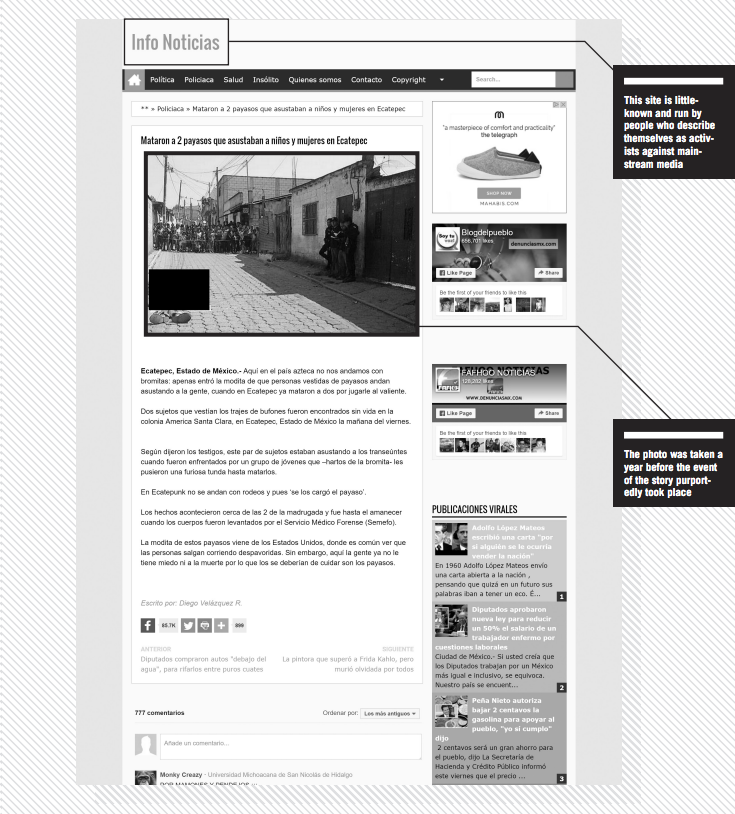

Decoding the News: Mexico

Not a Laughing Matter

DUNCAN TUCKER digs out the clues that a story about clown killings in Mexico didn’t stand up

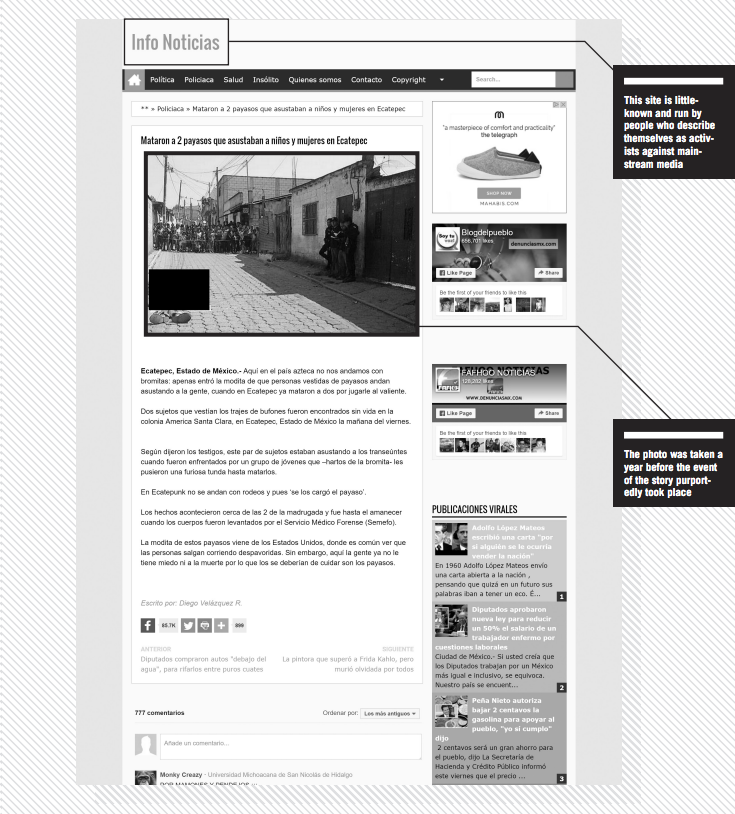

Disinformation thrives in times of public anxiety. Soon after a series of reports on sinister clowns scaring the public in the USA in 2016, a story appeared in the Mexican press about clowns being beaten to death.

At the height of the clown hysteria, the little-known Mexican news site DenunciasMX reported that a group of youths in Ecatepec, a gritty suburb of Mexico City, had beaten two clowns to death in retaliation for intimidating passers-by. The article featured a low-resolution image of the slain clowns on a run-down street, with a crowd of onlookers gathered behind police tape.

To the trained eye, there were several telltale signs that the news was not genuine.

While many readers do not take the time to investigate the source of stories that appear on their Facebook newsfeeds, a quick glance at DenunciasMX’s “Who are we?” page reveals that the site is co-run by social activists who are tired of being “tricked by the big media mafia”. Serious news sources rarely use such language, and the admission that stories are partially authored by activists rather than by professionally-trained journalists immediately raises questions about their veracity.

The initial report was widely shared on social media and quickly reproduced by other minor news sites but, tellingly, it was not reported in any of Mexico’s major newspapers – publications that are likely to have stricter criteria with regard to fact-checking.

Another sign that something was amiss was that the reports all used the vague phrase “according to witnesses”, yet none had any direct quotes from bystanders or the authorities

Yet another red flag was the fact that every news site used the same photograph, but the initial report did not provide attribution for the image. When in doubt, Google’s reverse image search is a useful tool for checking the veracity of news stories that rely on photographic evidence. Rightclicking on the photograph and selecting “Search Google for Image” enables users to sift through every site where the picture is featured and filter the results by date to find out where and when it first appeared online.

In this case, the results showed that the image of the dead clowns first appeared online in May 2015, more than a year before the story appeared in the Mexican press. It was originally credited to José Rosales, a reporter for the Guatemalan news site Prensa Libre. The accompanying story, also written by Rosales, stated that the two clowns were shot dead in the Guatemalan town of Chimaltenango.

While most of the fake Mexican reports did not have bylines and contained very little detail, Rosales’s report was much more specific, revealing the names, ages and origins of the victims, as well as the number of shell casings found at the crime scene. Instead of rehashing rumours or speculating why the clowns were targeted, the report simply stated that police were searching for the killers and were working to determine the motive.

As this case demonstrates, with a degree of scrutiny and the use of freely available tools, it is often easy to differentiate between genuine news and irresponsible clickbait.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

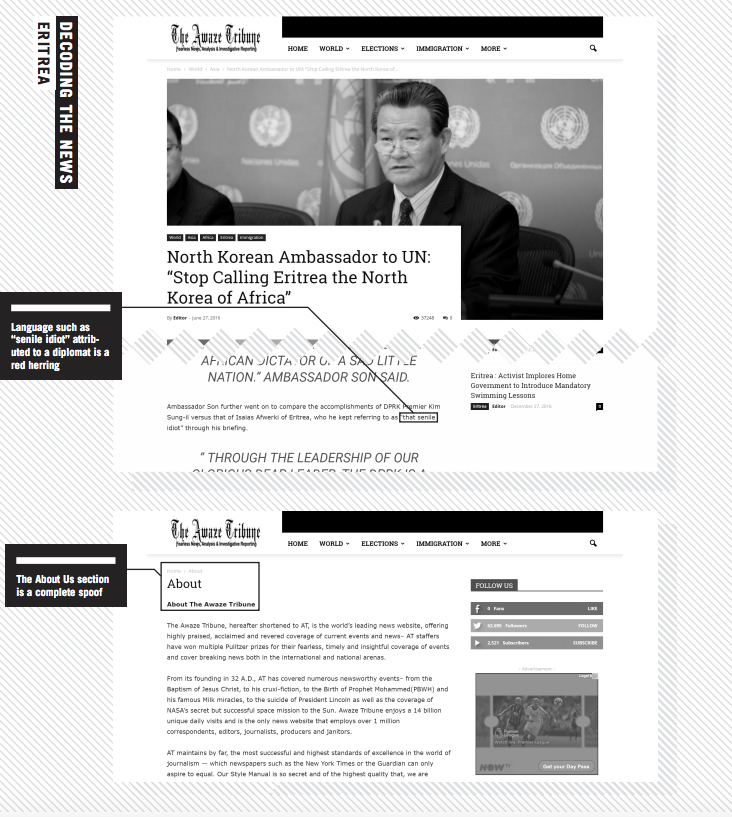

Decoding the News: Eritrea

Not North Korea

ABRAHAM T ZERE dissects the moment that Eritreans mistook saucy satire for real news

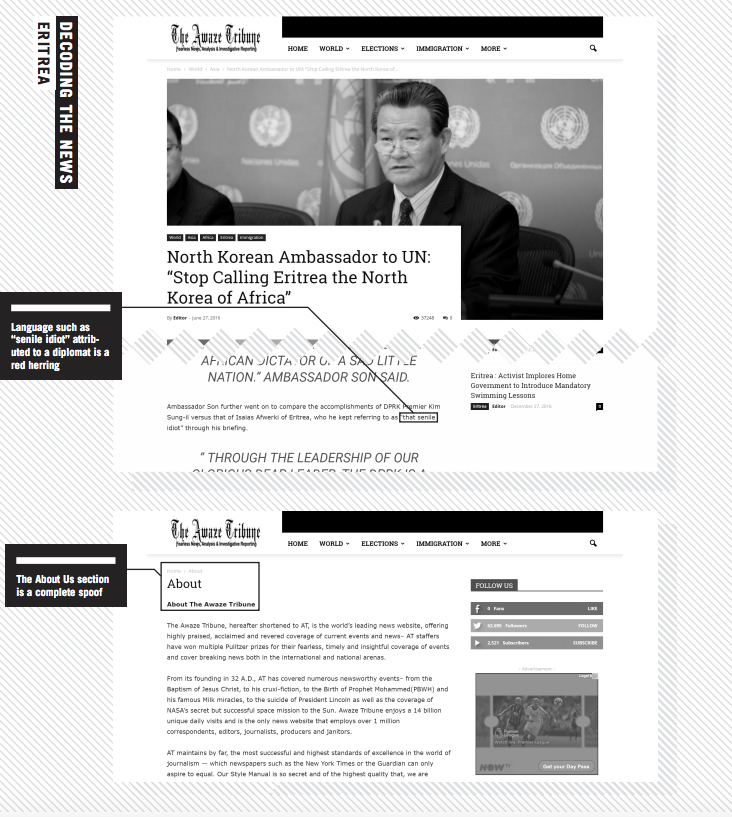

In recent years, the international media have dubbed Eritrea the “North Korea of Africa”, due to their striking similarities as closed, repressive states that are blocked to international media. But when a satirical website run by exiled Eritrean journalists cleverly manipulated the simile, the site stoked a social media buzz among the Eritrean diaspora.

Awaze Tribune launched last June with three news stories, including “North Korean ambassador to UN: ‘Stop calling Eritrea the North Korea of Africa’.”

The story reported that the North Korean ambassador, Sin Son-ho, had complained it was insulting for his advanced, prosperous, nuclear-armed nation to be compared to Eritrea, with its “senile idiot leader” who “hasn’t even been able to complete the Adi Halo dam”.

With apparent little concern over its authenticity, Eritreans in the diaspora began widely sharing the news story, sparking a flurry of discussion on social media and quickly accumulating 36,600 hits.

The opposition camp shared it widely to underline the dismal incompetence of the Eritrean government. The pro-government camp countered by alleging that Ethiopia must have been involved behind the scenes.

The satirical nature of the website should have seemed obvious. The name of the site begins with “Awaze”, a hot sauce common in Eritrean and Ethiopian cuisines. If readers were not alerted by the name, there were plenty of other pointers. For example, on the same day, two other “news” articles were posted: “Eritrea and South Sudan sign agreement to set an imaginary airline” and “Brexit vote signals Eritrea to go ahead with its long-planned referendum”.

Although the website used the correct name and picture of the North Korean ambassador to the UN, his use of “senile idiot” and other equally inappropriate phrases should have betrayed the gag.

Recently, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has been spending time at Adi Halo, a dam construction site about an hour’s drive from the capital, and he has opened a temporary office there. While this is widely known among Eritreans, it has not been covered internationally, so the fact that the story mentioned Adi Halo should also have raised questions of its authenticity with Eritreans. Instead, some readers were impressed by how closely the North Korean ambassador appeared to be following the development.

The website launched with no news items attributed to anyone other than “Editor”, and even a cursory inspection should have revealed it was bogus. The About Us section is a clear joke, saying lines such as the site being founded in 32AD.

Satire is uncommon in Eritrea and most reports are taken seriously. So when a satirical story from Kenya claimed that Eritrea had declared polygamy mandatory, demanding that men have two wives, Eritrea’s minister of information felt compelled to reply.

In recent years, Eritrea’s tightly closed system has, not surprisingly, led people to be far less critical of news than they should be. This and the widely felt abhorrence of the regime makes Eritrean online platforms ready consumers of such satirical news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: South Africa

And That’s a Cut

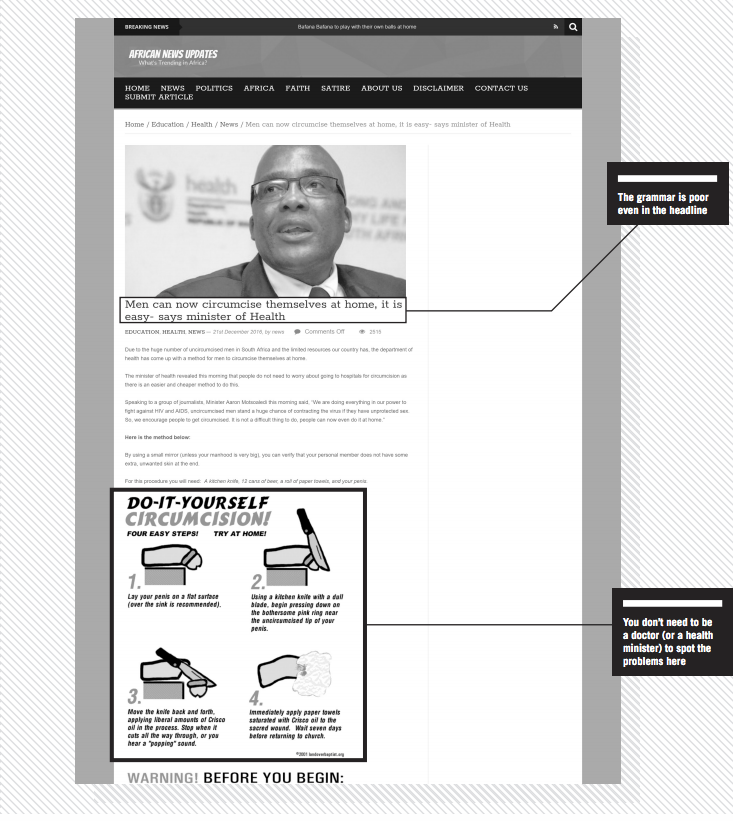

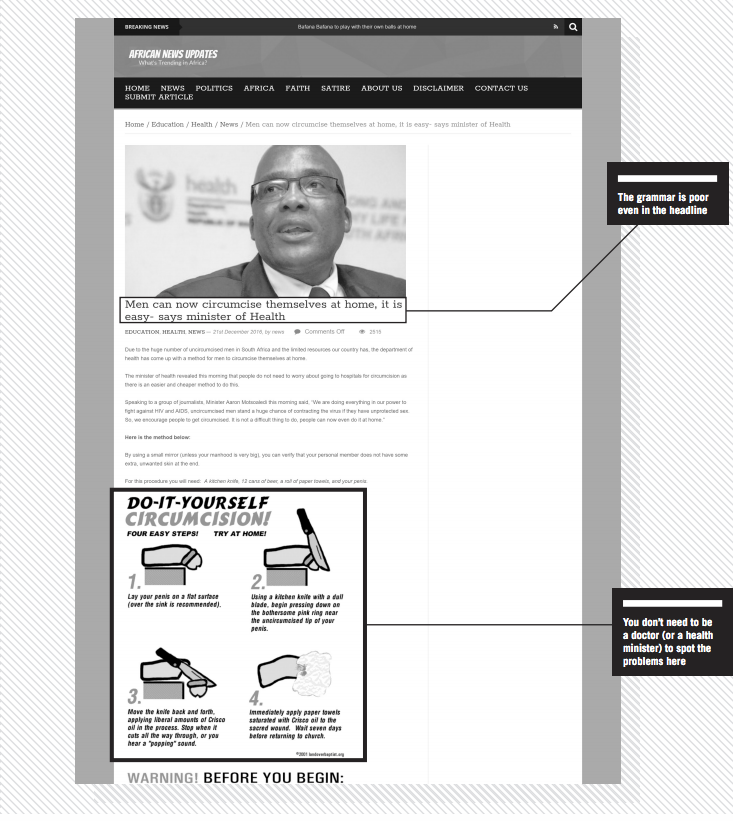

Journalist NATASHA JOSEPH spots the signs of fiction in a story about circumcision

The smartest tall tales contain at least a grain of truth. If they’re too outlandish, all but the most gullible reader will see through the deceit. Celebrity death stories are a good example. In South Africa, dodgy “news” sites routinely kill off local luminaries like Desmond Tutu. The cleric is 85 years old and has battled ill health for years, so fake reports about his death are widely circulated.

This “grain of truth” rule lies at the heart of why the following headline was perhaps believed. The headline was “Men can now circumcise themselves at home, it is easy – says minister of health”. Circumcision is a common practice among a number of African cultural groups. Medical circumcision is also on the rise. So it makes sense that South Africa’s minister of health would be publicly discussing the issue of circumcision.

The country has also recently unveiled “DIY HIV testing kits” that allow people to check for HIV in their own homes. This is common knowledge, so casual or less canny readers might conflate the two procedures.

The reality is that most of us are casual readers, snacking quickly on short pieces and not having the time to engage fully with stories. New levels of engagement are required in a world heaving with information.

The most important step you can take in navigating this terrible new world is to adopt a healthy scepticism towards everything. Yes, it sounds exhausting, but the best journalists will tell you that it saves a lot of time to approach information with caution. My scepticism manifests as what I call my “bullshit detector”. So how did my detector react to the “DIY circumcision” story?

It started ringing instantly thanks to the poor grammar evident in the headline and the body of the text. Most proper news websites still employ sub editors, so lousy spelling and grammar are early warning signals that you’re dealing with a suspicious site.

The next thing to check is the sourcing: where did the minister make these comments? To whom? All this article tells us is that he was speaking “in Johannesburg”. The dearth of detail should signal to tread with caution. If you’ve got the time, you might also Google some key search terms and see if anyone else reported on these alleged statements. Also, is there a journalist’s name on the article? This one was credited to “author”, which suggests that no real journalist was involved in production.

The article is accompanied by some graphic illustrations of a “DIY circumcision”. If you can stomach it, study the pictures. They’ll confirm what I immediately suspected upon reading the headline: this is a rather grisly example of false “news”.

Finally, make sure you take a good look at the website that runs such an article. This one appeared on African News Updates.

That’s a solid name for a news website, but two warning bells rang for me: the first bell was clanged by other articles, which ranged from the truth (with a sensational bent) to the utterly ridiculous. The second bell rang out of control when I spotted a tab marked “satire” along the top. Click on it and there’s a rant ridiculing anyone who takes the site seriously. Like I needed any excuse to exit the site and go in search of real news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: How To

Get the Tricks of the Trade

Veteran journalist RAYMOND JOSEPH explains how a handy new tool from South Africa can teach you core journalism skills to help you get to the truth

It’s been more than 20 years since leading US journalist and journalism school teacher Melvin Mencher released his Reporter’s Checklist and Notebook, a brilliant and simple tool that for years helped journalists in training.

Taking cues from Mencher’s, there’s now a new kid on the block designed for the digital age. Pocket Reporter is a free app that leads people through the newsgathering process – and it’s making waves in South Africa, where it was launched in late 2016.

Mencher’s consisted of a standard spiral-bound reporter’s notebook, but also included tips and hints for young reporters and templates for a variety of stories, including a crime, a fire and a car crash. These listed the questions a journalist needed to ask.

Cape Town journalist Kanthan Pillay was introduced to Mencher’s notebook when he spent a few months at the Harvard Business School and the Nieman Foundation in the USA. Pillay, who was involved in training young reporters at his newspaper, was inspired by it. Back in South Africa, he developed a website called Virtual Reporter.

“Mencher’s notebook got me thinking about what we could do with it in South Africa,” said Pillay. “I believed then that the next generation of reporters would not carry notebooks but would work online.”

Picking up where Pillay left off, Pocket Reporter places the tips of Virtual Reporter into your mobile phone to help you uncover the information that the best journalists would dig out. Cape Town-based Code for South Africa re-engineered it in partnership with the Association of Independent Publishers, which represents independent community media.

It quickly gained traction among AIP’s members. Their editors don’t always have the time to brief reporters – who might be inexperienced journalists or untrained volunteers – before they go out on stories.

This latest iteration of the tool, in an age when any smartphone user can be a reporter, is aimed at more than just journalists. Ordinary people without journalism training often find themselves on the frontline of breaking news, not knowing what questions to ask or what to look out for.

Code4SA recently wrote code that makes it possible to translate the content into other languages besides English. Versions in Xhosa, one of South Africa’s 11 national languages, and Portuguese are about to go live. They are also currently working on Afrikaans and Zulu translations, while people elsewhere are working on French and Spanish translations.

“We made the initial investment in developing Pocket Reporter and it has shown real world value. It is really gratifying to see how the project is now becoming community-driven,” said Code4SA head Adi Eyal.

Editor Wara Fana, who publishes his Xhosa community paper Skawara News in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, said: “I am helping a collective in a remote area to launch their own publication, and Pocket Reporter has been invaluable in training them to report news accurately.” His own journalists were using the tool and he said it had helped improve the quality of their reporting.

Cape Peninsula University of Technology journalism department lecturer Charles King is planning to incorporate Pocket Reporter into his curriculum for the news writing and online-media courses he teaches.

“What’s also of interest to me is that there will soon be Afrikaans and Xhosa versions of the app, the first languages of many of our students,” he said.

Once it has been downloaded from the Google Play store, the app offers a variety of story templates, covering accidents, fires, crimes, disasters, obituaries and protests.

The tool takes you through a series of questions to ensure you gather the correct information you need in an interview.

The information is typed into a box below each question. Once you have everything you need, you have the option of emailing the information to yourself or sending it directly to your editor or anyone else who might want it.

Your stories remain private, unless you choose to share them. Once you have emailed the story, you can delete it from your phone, leaving no trace of it.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

This article originally appeared in the spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Kaya Genç is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine based in Istanbul, Turkey

Jemimah Steinfeld is deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Duncan Tucker is a regular correspondent for Index on Censorship magazine from Mexico

Journalist Abraham T Zere is originally from Eritrea and now lives in the USA. He is executive director of PEN Eritrea

Natasha Joseph is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is also Africa education, science and technology editor at The Conversation

Raymond Joseph is former editor of Big Issue South Africa and regional editor of South Africa’s Sunday Times. He is based in Cape Town and tweets @rayjoe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533808″][vc_custom_heading text=”There’s nothing new about fake news” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533808|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Andrei Aliaksandrau takes a look at fake news in Belarus[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532452″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fake news: The global silencer” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532452|||”][vc_column_text]April 2018

Caroline Lees examines fake news being used to imprison journalists [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229808536482″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taking the bait” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229808536482|||”][vc_column_text]April 2017

Richard Sambrook discusses the pressures click-bait is putting on journalism[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88802″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Apr 2017

About this report

This non-exhaustive study of threats to media freedom in the United States researched over 150 publicly reported incidents involving journalists. It uses the criteria developed for and employed by Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project launched in May 2014 that monitors the media landscape in 42 European and neighboring countries. This survey reviewed media freedom violations that occurred in the United States between June 30, 2016, and February 28, 2017.

Reports were submitted by a team of researchers. Each incident was then fact-checked by Index on Censorship against multiple sources.

Index on Censorship is a UK-based nonprofit that campaigns against censorship and promotes freedom of expression worldwide. Founded in 1972, Index has published some of the world’s leading writers and artists in its award-winning quarterly magazine, including Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Samuel Beckett and Kurt Vonnegut. Index promotes debate, monitors threats to free speech and supports individuals through its annual awards and fellowship program.

Acknowledgements

Author: Sally Gimson

Editor: Sean Gallagher

Research: Hannah Machlin,

Elise Thomas, Amanda James,

Laura Stevens, Alex Gibson,

Gary Dickson, Courtney Manning, Madeline Domenichella

Additional research/editing:

Ryan McChrystal, Melody Patry, Atticus O’Brien-Pappalardo,

Esther Egbeyemi, Samuele Volpe, Jemimah Steinfeld

Illustrations: Eva Bee

Design: Matthew Hasteley

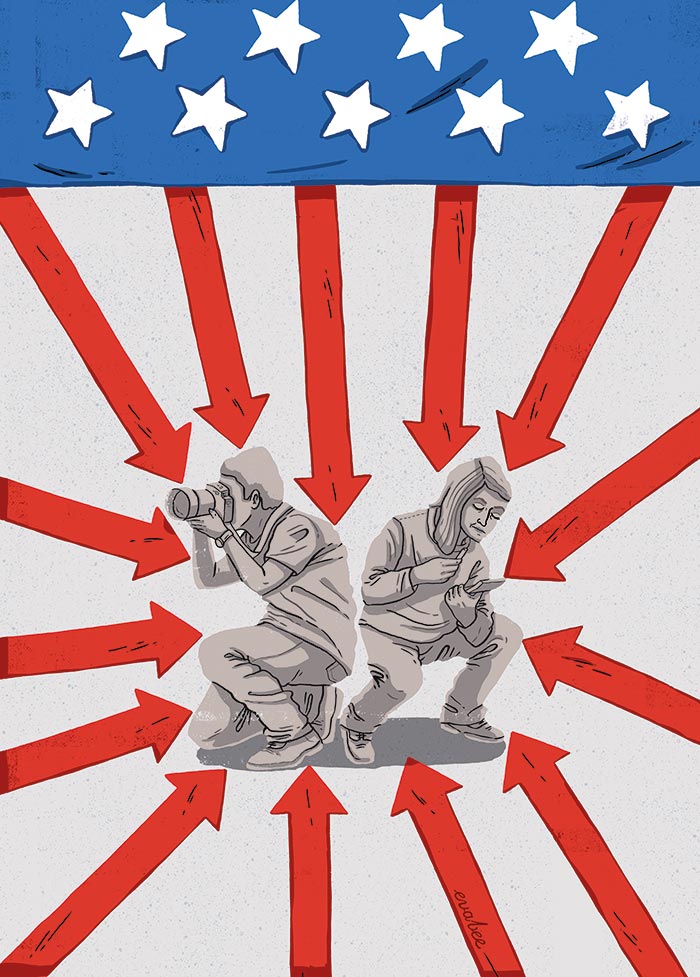

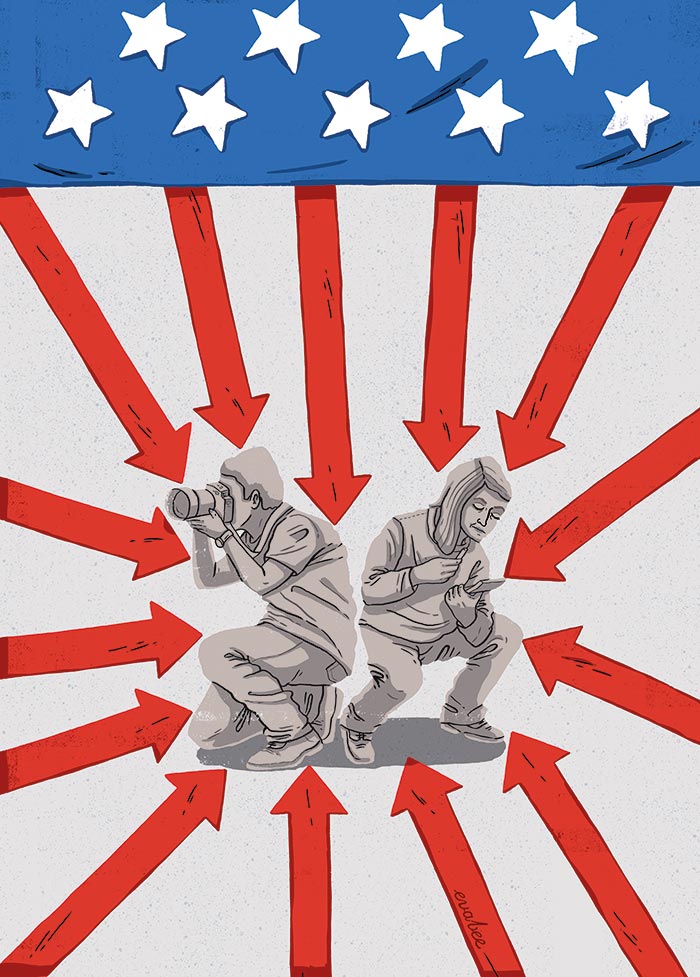

Smears about the media made by US President Donald Trump have obscured a wider problem with press freedom in the United States: namely widespread and low-level animosity that feeds into the everyday working lives of the nation’s journalists, bloggers and media professionals. This study examines documented reports from across the country in the six months leading up to the presidential inauguration and the months after. It clearly shows that threats to US press freedom go well beyond the Oval Office.

“Animosity toward the press comes in many forms. Journalists are targeted in several ways: from social media trolling to harassment by law enforcement to over-the-top public criticism by those in the highest office. The negative atmosphere for journalists is damaging for the public and their right to information,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO at Index on Censorship, which documented the cases using an approach undertaken by the organization to monitor press freedom in Europe over the past three years.

The US study shows journalists have been on the receiving end of online and offline harassment, as well as being arrested and charged with criminal offenses just for doing their job.

Reporters traveling into the country have also been caught up in the move to tighten border security, a trend that began during President Barack Obama’s administration but gathered pace after the Trump inauguration on January 20, 2017. Without clear guidelines, journalists have found themselves at the mercy of Customs and Border Protection agents who have seized and searched their electronic devices.

The arrests and border searches come as states are introducing new legislation or interpreting older laws in ways likely to have a detrimental effect on reporting.

For citizen reporters and freelancers, who do not have the protection of media organizations, the climate was already hostile and is now becoming more so. As the experience of Gawker has shown, even large media websites can be driven out of business if they rile the rich and powerful.

“Attention on the media has focused on the very public spat between Donald Trump and major news outlets,” Melody Patry, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship, said. “But this survey shows that threats to media freedom are far more deep-rooted and affect local journalists, bloggers and investigative reporters across the country. This is a serious cause for concern in a country that prides itself on the First Amendment principles protecting a free press.”

Arrests and detainments

The arrest of journalists covering demonstrations poses one of the largest direct threats to the freedom of reporters performing their professional duties. Not only are they physically removed from the protests but they are also being charged with serious criminal offenses. Previously journalists may have been charged with misdemeanors – the most serious of which only carries a large fine or up to a year in prison. Now they are being charged with felonies, which can carry decades in jail.

“This trend towards treating reporters at protests as active participants is alarming. Although these charges are most often dropped, the continuing arrests could cause journalists to think twice about covering a demonstration or reporting on police abuses against participants,” Hannah Machlin, project officer for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, said.

This pattern did not begin with the election of Trump. These decisions were also taken during the Obama administration by local law enforcement agencies and state attorneys.

Six journalists who were covering protests at Trump’s inauguration were arrested in the capital and charged with felonies, the most severe punishment under Washington DC’s law against rioting.

They included two reporters, a documentary producer, a photojournalist, a live-streamer and a freelance reporter. However, charges against four of the journalists were dropped nine days later. Charges against videographer Shay Horse were dismissed on February 21. Only freelance reporter Aaron Cantu remains charged with felony rioting.

Other examples of reporters targeted during protests include those covering the Dakota Access Pipeline and Black Lives Matter demonstrations discussed in more detail below.

More incidents suggest law enforcement officers need training and directives to respect journalists’ rights to cover events – like the case of Chris Hayes, a Fox 2 St. Louis journalist, who on June 30, 2016, was handcuffed and shackled to a bench in Kinloch, Missouri. He was detained after objecting to being barred from a public meeting on uninsured and unregistered police cars, a story that Fox 2 had originally investigated. Hayes was issued a court summons for failure to comply and disorderly conduct.

North Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and associated protests

Several journalists and documentary filmmakers covering protests against the controversial oil pipeline project have been arrested and charged with felonies.

The law enforcement response to protesters and reporters has been increasingly militarized in the state according to the American Civil Liberties Union. In August 2016 the former governor of North Dakota Jack Dalrymple (R) declared a state of emergency.

Among journalists arrested and charged were Amy Goodman, host of the news program Democracy Now! She was taken into custody on September 3, 2016, after she filmed private security guards employed by Dakota Access LLC using dogs and pepper spray to disperse the protests against construction work. Her video has been viewed over 14 million times on Facebook. At first Goodman was charged with a misdemeanor offense of criminal trespass, but that was escalated by the state attorney to a rioting felony. A district judge finally dismissed the charges in October.

I don’t see why I would not be allowed to get a photo of peaceful protesters being arrested. If that is off limits, what else is?

In another pipeline protest, documentary filmmaker Deia Schlosberg was detained while filming a demonstration on October 11, 2016, where climate change activists manually closed off the TransCanada Keystone Pipeline in Walhalla, North Dakota, which brings tar sands oil across the border from Canada. It was one of five similar demonstrations that day held by climate change activists as an act of solidarity with the campaign against the DAPL. Schlosberg was charged with three offenses which could have landed her in prison for 45 years: conspiracy to theft of property, conspiracy to theft of services and conspiracy to tampering with or damaging a public service. The charges were eventually suspended and will be formally dropped, but only if she commits no further crimes for six months. Schlosberg told The Guardian that she hasn’t covered a protest since October to avoid serious consequences were she to be arrested again, demonstrating the effect that such actions can have on journalism.

On the same day, at another protest near Skagit County in Washington state, documentary producer Lindsey Grayzel and her cinematographer Carl Davis were arrested and held for 24 hours for filming activist Ken Ward manually closing off the Trans Mountain pipeline. Grayzel is in the process of making a documentary about Ward.

Though neither Grayzel nor Davis were on pipeline property, they were charged with second-degree burglary, criminal sabotage and assemblage of saboteurs, all felony cases which could lead to a 30-year prison sentence. The charges were ultimately dismissed, but Grayzel said the police still had her memory cards with footage on them, her phone and her notes.

The charges against other filmmakers, who also filmed activists on October 11, are still pending and they could still face prison sentences.

CASE STUDY: TRACIE WILLIAMS

Tracie Williams is an experienced documentary photographer. She had been covering the main protest camp at Standing Rock for three weeks before she was arrested on February 23, 2017, during a police operation to evict protesters from the site. She says the police arrived at the camp with humvees, helicopters and automatic weapons. “I feared for the protesters’ safety and felt a duty to photograph their imminent arrests,” Williams said, recalling the photograph she made as members of the Morton County Sheriff’s Department advanced towards two men praying near the sacred fire with weapons aimed at them at point-blank range. Officers approached her from the side, without notice or warning, Williams said, and she was arrested while photographing the arrests. She was covering the protest for the National Press Photographers’ Association and told police she was a journalist, but they did not seem to care, she added.

Williams was handcuffed with zip ties and transported first to the Morton County Sheriff’s Department, where she, along with seven other women were held in chain-link cages in a drafty garage. They were asked to strip down to their base layers and all their belongings, including their jackets, were placed in clear plastic bags. They were then transferred to McLean County, where they were charged with “Obstruction of Gov. Function.” The plastic ties they used to handcuff her, she said, have caused her nerve damage. She now faces a class A misdemeanor charge, which carries a possible sentence of up to a year in prison and $3K in fines. All of her gear including her camera, phone, audio recorder and memory cards, were confiscated as evidence. Williams got the equipment back but not until she had harnessed help from two lawyers, several advocacy groups and a local senator. She is still facing charges in North Dakota.

Black Lives Matter protests

Journalists at Black Lives Matter and similar demonstrations have been arrested by police, even though they clearly identified themselves as members of the press.

Ryan Kailath was on an assignment for National Public Radio covering the New Black Panthers protests in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on July 9, 2016, when he was arrested. The incident took place following the killing of Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old black man, by Baton Rouge police officers. Kailath said he was standing on a grass verge covering the protests but as things got violent he retreated into another line of police officers who arrested him. Kailath said he repeatedly identified himself as a journalist but was ignored. As he tweeted on July 11, a police officer said to him: “I’m tired of y’all saying you’re journalists.” Kailath explained that when he was arrested, the police identified him as a black man although he is an Indian-American.

Kailath said of his experience: “I was transferred between six locations, searched naked, given an orange jumpsuit and a medical and mental health screening, and finally checked in to the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison. In the morning, we were given the local paper, The Advocate. It was only when an inmate paging through it looked up at me and said: ‘Hey, you’re in here!’ that I learned I was being charged with simple obstruction of a highway.” Within the week all charges against him had been dropped.

I was transferred between six locations, searched naked, given an orange jumpsuit and a medical and mental health screening, and finally checked in to the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison

Two other journalists were also arrested at the same demonstration. WAFB (a CBS-affiliated TV station for Baton Rouge) assistant news editor Chris Slaughter, who was clearly identified by his staff shirt and media credentials, and Breitbart News reporter Lee Stranahan were charged with obstruction of a highway.

Two black reporters were briefly handcuffed by police in Rochester, New York during similar protests over the shooting of black men. Carlet Cleare and Justin Carter of WHAM-TV were detained in the early hours of July 9, 2016, for a short time before being released with a public apology from the mayor and chief of police.

On August 22, 2016, in Asheville, North Carolina, Dan Hesse, a reporter for the local paper Mountain Xpress, was arrested while covering a sit-in protest by Black Lives Matter. He was with protesters who were occupying the lobby of the police and fire department when it was cleared by police. He told officers and protesters he was a journalist. He was nevertheless arrested and charged, though charges were dropped a week later. “I don’t see why I would not be allowed to get a photo of peaceful protesters being arrested,” said Hesse. “If that is off limits, what else is?”

On November 9, 2016, two reporters, Jason Silverstein and EJ Fox, were arrested while covering protests outside Trump Tower in New York. Silverstein said in an article for the Daily News, New York that he was handcuffed with plastic ties by a police officer who accused him of blocking the sidewalk. He was charged with disorderly conduct and refusing an order to disperse. Fox said he was held from 9pm until 2am and considered himself lucky, but hoped that the behavior of the NYPD had not been affected by the Trump presidency.

US border detentions

Many journalists have found themselves detained at the US border. Over the period covered by the survey, there were several reports of journalists being stopped by US Customs and Border Protection agents, detained and asked to hand over equipment and notes. Some of these incidents occurred before Trump was elected and before he signed an executive order for a travel ban. According to NBC News, data provided by the Department of Homeland Security shows that searches of all travelers’ phones by border agents has grown fivefold in just one year, from fewer than 5,000 in 2015 to nearly 25,000 in 2016. DHS officials told the network that 2017 would be a “blockbuster” year. Some 5,000 devices were searched in February 2017 alone, as many as in all of 2015.

The most disturbing aspect of these detentions is that journalists (and indeed any US citizen) can have their phones and electronic equipment searched at the border without customs officers or Homeland Security officials having to prove any suspicion of wrongdoing. Only journalists and US citizens actually inside the country are protected by a 2014 Supreme Court ruling which says police must get warrants to search phones. Otherwise they have no protection under the Fourth Amendment at the border.

Customs and Border Protection officials should respect the right of journalists to protect confidential information, and refrain from demanding access to people’s devices and passwords

In one incident, a Wall Street Journal Middle East correspondent and US citizen, Maria Abi-Habib, was detained on July 14, 2016, by border control officers at Los Angeles International Airport and asked for access to her two phones. She recounted in a Facebook post how she managed to hold them off by threatening to call WSJ lawyers because the phones were the property of her employer. Another journalist, Kim Badawi, was held at Miami International Airport for 10 hours when he flew in from Rio for Thanksgiving. A US citizen who works for Le Monde in Rio, Badawi was questioned by Customs and Border Protection agents about his passport stamps for Middle Eastern countries, his political views and his religious affiliation. His baggage was searched and he was forced to surrender the password of his phone so agents could go through all of his contacts, photos and messages, including confidential WhatsApp messages from Syrian refugees. Badawi wrote a first-person account of his experience for the Huffington Post.

After the travel ban was imposed in January, more journalists found themselves detained. BBC journalist Ali Hamedani, a British citizen born in Iran, live tweeted his detention. He was held for two hours on January 29, 2017, and said he was subjected to “invasive checks” after he had flown into Chicago. Hamedani said he was forced to hand over his phone and its password. Sama Dizayee, a Washington-based Iraqi journalist who planned to fly to London in February 2017, told NPR she was afraid to travel because of her belief that she might not be allowed back in the country. Although she has a green card, she said, she had no certainty that her rights to live in the USA would be guaranteed if she left and tried to come back into the country. Meanwhile, senior CNN editor Mohammed Tawfeeq filed a lawsuit against the travel ban after being detained at Atlanta’s airport over the weekend of January 28 and 29, the days following Trump’s signing of the travel ban executive order. He is an Iraqi citizen with a US green card. The lawsuit argued that officials have used Trump’s executive order “to subject returning residents like Mr. Tawfeeq to inappropriate exercises of discretion with regard to their right to return to the United States, and to lengthy delays and interrogations at ports of entry”.

“Officials should respect the right of journalists to protect confidential information and refrain from demanding access to people’s devices, online accounts and passwords. Journalists must be aware of possible requests by border agents, which may compromise their security and that of their sources,” Mapping Media Freedom’s Machlin said.

CASE STUDY: ED OU

Ed Ou, an award-winning Canadian photojournalist, tried to cross the US-Canadian border to cover the Dakota Access Pipeline protests on October 1, 2016. He found himself detained for six hours, had his phone searched, his journal photocopied and was then refused entry. Border security was not interested in Ou’s concerns about protecting his sources. In a letter to Customs and Border Protection and Homeland Security, American Civil Liberties Union attorney Hugh Handeyside wrote: “[W]e believe that CBP took advantage of Mr. Ou’s application for admission to engage in an opportunistic fishing expedition for sensitive and confidential information that Mr. Ou had gathered through his newsgathering activities in Turkey, Somalia, Iraq and elsewhere.”

Most of the physical assaults against journalists across the country have been at demonstrations. For instance, on August 14, 2016, two reporters were physically attacked by about a dozen people in Milwaukee during violent demonstrations against the police shooting of Sylville Smith, a black man who was killed fleeing a traffic stop. The reporters were filming a BP gas station which had been set on fire by protesters. Their equipment, including cameras and satellite packs, was stolen and one of the journalists had to go to hospital for an evaluation. At a Black Lives Matter protest, which took place on September 21 in Charlotte, Virginia, Mary Sturgill, an anchor for the Columbia, South Carolina, station WLTX, was tackled by demonstrators and her photographer was punched.

The only solution is a greater awareness of both media organizations and police departments

On October 18, 2016, in North Dakota, activists at the Sacred Stone Camp were accused of assaulting journalist Phelim McAleer, who was making a documentary called FrackNation in favor of fracking. His microphone was taken away and he was assaulted after he asked DAPL protesters about their use of fossil fuels. When McAleer and colleagues went back to their car, a group of about 30 individuals surrounded the vehicle and the journalists were forced to call the police for help.

On November 3, 2016, during “water protector” protests over the DAPL at Standing Rock Indian Reservation, journalist and activist Erin Schrode said she was hit by a rubber bullet from “militarized police” while she was in the middle of an interview. The impact of the bullet knocked her over. She posted a video of the incident on Facebook.

Journalists were also targeted at election protests. In Portland, Oregon, a woman spat in the camera of a news crew covering demonstrations in the early hours of November 9, as the election results were being reported. The woman, who was an anti-Trump protester, yelled directly into the KOIN 6 News camera held by video journalist Karl Petersen before spitting.

During separate protests in north Baltimore on the evening of November 9, Fox45 reporter Keith Daniels and photographer Ruth Morton had to be moved to safety by police. An angry crowd had surrounded them and ordered them to leave the scene. The end of the encounter was broadcast live on Fox45. Daniels reported that this had never happened to him before. The crowd had told him they did not believe that he would put the “correct narrative” on his coverage.

The inauguration protests in Washington DC on January 20, 2017, also turned violent. Photographer Vanessa Koolhof, working for ABC affiliate news station WJLA, was knocked over and injured in the middle of a stand-off near the National Mall when a Trump supporter came into the crowd and police tried to break up scuffles. She was slightly injured before being assisted by police officers.

There have been other physical incidents against journalists in the period. For instance, a reporter and photographer from NBC6 were injured on November 21, 2016, when a man drove a stolen SUV into the news crew’s car in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. In December 2016, a woman accused of faking her own abduction threatened a reporter from the same TV station and shouted at a photographer. She said: “I will knock your ass out. Get that shit out of my face.” She also threw a rock at another station’s crew and was detained by police. She was released after the crews declined to press charges.

Having equipment stolen is an occupational hazard in some areas. In two incidents within a week of each other in the San Francisco East Bay area, reporters had their cameras stolen. In the first incident, on September 19, a field manager from KGO TV had his camera taken from him at gunpoint by two men in Alameda near Robert W Crown Memorial State Beach. On September 23, Raquel Maria Dillon, a multimedia journalist with NBC Bay Area, was approached by a man who pulled her camera from her hands. She had just finished covering a story and was walking back to her car when she was attacked. As a result of these and other robberies, some news organizations in the area have hired security guards to look after their journalists and crews.

In Niagara Falls on October 22, a reporter and photographer from the local Buffalo station WIVB, a CBS affiliate, were cornered in an alley by four men with a gun, who asked them for money and for the camera. The crew was out covering an art installation when they were physically attacked: the photographer had to go to the hospital and the reporter suffered minor injuries. On October 13, 2016, in Bedford County, Virginia, Tim Saunders, a reporter from local station WDBJ7, was shot at when he was in the station’s vehicle. A mentally ill 18-year-old was wandering around the streets with a rifle shooting at vehicles and knocking on doors before he was arrested. Saunders was unhurt and no one else was injured in the incident.

“Journalist safety must be taken extremely seriously by law enforcement. Whether the perpetrators of violence are police officers or private citizens, violence against journalists, cases of robbery or harassment must be investigated vigorously and charges filed promptly to ensure that a culture of impunity is unable to take root,” Mapping Media Freedom’s Machlin said.

CASE STUDY: DALTON BENNETT

Dalton Bennett, a video reporter for the Washington Post, has experience covering demonstrations all over the world, from Greece to the Arab Spring. He was filming demonstrators on inauguration day when he was pushed over and grabbed by a police officer. Most of the protesters were peaceful, he said, but a smaller group of black bloc protesters were causing trouble, which was unusual for Washington DC. At one point during the protest “all hell was breaking loose” and the police began using pepper spray and stun grenades before kettling the protesters.

“In the process of getting kettled, we’re filming it, which is what a video reporter is supposed to be doing, and a police officer felt that I was too close, and decided to get me away from the situation and so pushed me,” Bennett said. “My backpack was being grabbed and I was pushed by another guy and fell to the ground in the process. I wouldn’t say it was a concerted effort to prevent us from capturing the moment, there were a lot of journalists there. I think it was, more than anything, just a police officer, just authorities generally caught up in this ebb and flow of the demonstration. I mean I don’t think it was done out of malice, or to prevent us reporting. That being said, I don’t think it was necessary at all, it definitely wasn’t necessary, and the city itself has issued a report saying some of its tactics weren’t exactly kosher.”

Bennett doesn’t believe the right to film protests is under threat in the USA, but he said: “Inevitably as more and more protests happen across the country, this is a question which is going to continue to arise. I think the only solution is a greater awareness of both media organizations and police departments on the role that the media plays in covering these protests and better practice among media organizations, [understanding] how demonstrations work, how to keep safe covering the protest.”

Criminal charges / civil lawsuits

Since the election of Trump there has been anxiety around his claims that he would loosen US libel laws. At a rally in Fort Worth, Texas in February 2016 Trump declared: “I’m going to open up our libel laws so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money.”

However, current US libel laws have already led to one news organization, Gawker, closing after a lawsuit alleging the site had invaded the privacy of a celebrity.

Others, like conservative political commentator and television host Glenn Beck, have found themselves on the receiving end of defamation suits. Beck, along with other journalists, including commentators from Fox News, were sued for the comments they made about a boy who brought a clock to school in a suitcase and was arrested in September 2015 after it was mistaken for a bomb. The boy from Irving, Texas, was quickly released, but Beck suggested on a show aired by The Blaze that the clock bomb hoax story was possibly a conspiracy to “turn Texas blue [Democrat]”. The boy’s father filed a lawsuit. However, a judge ruled on January 9, 2017, that Beck’s free speech was protected under the First Amendment.

Most criminal charges against media professionals have been related to journalists caught up in protests, which we have detailed above.

However, there is another worrying case of a publisher from Blue Ridge, Georgia, and his attorney, who were arrested on June 24, 2016, for requesting public records. They were charged with three felonies – identity fraud, attempted identity fraud and making a false statement on an open records request – which carries up to 20 years in prison. Fannin Focus publisher, Mark Thomason, said he was held for two days before being granted bail, but only after a $10,000 bond had been posted. An outcry in the national press led to the charges being dismissed three weeks later. Thomason and attorney Russell Stookey were charged in part because they requested copies of checks written on the operating accounts of the judge’s office, which were “cashed illegally”. Chief Judge Brenda Weaver, who presides in the three-county Appalachian Judicial Circuit, had urged the district attorney to seek an indictment. Weaver, who was in control of one of those accounts, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution she pushed for the case because “I don’t react well when my honesty is questioned.” She was eventually forced to resign.

“US libel law has long been a model for the rest of the world. Lowering the burden of proof or otherwise loosening restrictions on lawsuits would pose a serious threat to press freedom in the country. At the same time, the misuse of the criminal justice system to silence journalists is a common occurrence in some European countries. This is not something that journalists in the USA should be exposed to,” Index’s Patry said.

CASE STUDY: GAWKER

Gawker went bankrupt and was shut down in August 2016 after a jury in Florida awarded $140 million in damages against it for invading the privacy of Hulk Hogan by publishing a sex tape of the celebrity wrestler. The lawsuit was funded by Peter Thiel, the co-founder of PayPal. Thiel told the Wall Street Journal: “I am supporting other people who have been harmed by Gawker, which routinely relied on an expectation that their less wealthy victims would have no legal recourse even against clear violations. I do not support legal actions against any other organizations.” Gawker’s assets were sold out of bankruptcy to Univision Communications Inc, and the publishers eventually settled with Hogan and others connected with the privacy suit in November 2016.

Legal measures

What laws are passed and how the law is interpreted can have an impact on journalists’ ability to report. Even when laws are not intended to restrict access to public information, they can be used to do so.

For instance, the so-called Marsy’s Law, which protects victims’ rights, has been enacted by some states. Although not its original intention, the law is being used by police forces in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, to justify withholding all information about crime locations, car accidents and crash victims in the area from journalists, according to a report in the Argus Leader on December 4, 2016. Journalists and others argue the law states that information should only be withheld “on request of the victim” and so a blanket ban on information is not justified. Similar laws have now been passed in North Dakota and Montana.

Another law, proposed by Utah State Representative Scott Chew (R) on January 31, 2017, to ban drones near livestock – with jail time for those who do – has faced criticism. Chew argues the drones may harass farm animals.

“Even well-intentioned laws can have a deleterious effect on journalists. In the case of Utah, the proposed legislation could penalize reporters doing investigative pieces around animal welfare and food safety. Even the Humane Society of the United States has expressed reservations about the draft bill,” Index’s Patry said.

The other pattern that is emerging concerns journalists who, all over the country, are being asked to hand over unpublished documents they have used in investigations, potentially compromising key sources. State “shield” laws should give legal protections for journalists, but this principle is being increasingly challenged. In Nashville, Tennessee, television reporter Phil Williams, who reported on the district attorney Glen Funk, was told by a judge on February 2, 2017, to hand over key documents. To add further pressure Funk has filed a $200 million defamation suit against the journalist and his employer, News Channel 5. The channel has condemned the actions as “an attempt by an elected public official to silence and intimidate a journalist and news organization that has accurately reported on questionable conduct and judgment by that official”.

Meanwhile in San Bernardino, California on January 17, 2017, a judge ruled that numerous journalists will have to take the stand in a corruption case on which they had reported. Prosecutors want them to testify on 56 statements contained in stories dating back 12 years. Journalists fear taking the stand because they may be forced under oath to compromise their sources.

CASE STUDY: PUBLIC BROADCASTERS

A provision added into the National Defense Authorization Act signed into law on December 23, 2016, has abolished the bipartisan board running Voice of America, Radio Free Europe and other news outlets. The board is to be replaced with a single chief executive appointed by the US president. Supporters argue that the change will make the $800 million media operation more efficient, but critics say it will give the president the ability to jeopardize the political independence of the operation.

“Politically independent public broadcasters are a vital segment of the media landscape at a time of increased propaganda. We’ve documented a series of moves by European governments to nationalize the public media in ways that make it more likely to toe the ruling party’s line,” Index’s Ginsberg said.

Works censored or altered

There is little information about works censored during the period we examined. This may well be because journalists tend not to report these kinds of incidents out of fear of negative repercussions for their career or because the pressure is more subtle. The case study below, however, is taken from a New York Times article from February 17, 2017.

On university campuses, there were more published examples of censored works. A report entitled Threats to the Independence of Student Media, published in October 2016 by the American Association of University Professors and others, explains how “college and university officials threatened retaliation against students and [media] advisers not only for coverage critical of the administration but also for otherwise frivolous coverage that the administrators believed placed the institution in an unflattering light.” The document details particular cases, including when “California’s Southwest College mounted a campaign of intimidation and bullying of student journalists – including freezing the newspaper’s printing budget, cutting the adviser’s salary and even threatening staff members with arrest – as part of an effort to conceal high-level wrongdoing.” There are many other examples given in the report of censorship and intimidation on campus, and of media advisers who have lost their jobs or been demoted as a result of not exercising enough censorship.

CASE STUDY: RICK CASEY

Rick Casey is the host of a show called Texas Week for San Antonio television station KLRM. At the end of every show he presents a short commentary. On this occasion, Republican representative from Texas, Lamar Smith, was on his agenda for giving a speech on January 24, 2017, about the unfair way he believed the media covered Trump. Smith suggested the only way of getting the truth was from the president himself. Casey was so outraged that he ended his commentary: “Smith’s proposal is quite innovative for America. We’ve never really tried getting all our news from our top elected official. It has been tried elsewhere, however. North Korea comes to mind.” Some 40 minutes before the show, the president of the station, Arthur Rojas Emerson, called Casey to tell him the commentary had been pulled. Emerson said he was worried that the commentary could affect the financing of the station, which is publicly funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. It was also the case, as The New York Times reported, that Emerson had left journalism for several years to work in advertising and Smith had been a client. After the affair was publicized in a local newspaper column, another prominent local journalist took Casey’s censored commentary up with the PBS board and Emerson finally agreed to run the clip. He admitted to the Times it was a “mistake”, but he only had 20 minutes to make a decision. Casey is 70 years old and said that he was more ready to push back because of his age. He said he didn’t know whether he would have acted differently at 45, when it could have affected his career.

Rick Casey is the host of a show called Texas Week for San Antonio television station KLRM. At the end of every show he presents a short commentary. On this occasion, Republican representative from Texas, Lamar Smith, was on his agenda for giving a speech on January 24, 2017, about the unfair way he believed the media covered Trump. Smith suggested the only way of getting the truth was from the president himself. Casey was so outraged that he ended his commentary: “Smith’s proposal is quite innovative for America. We’ve never really tried getting all our news from our top elected official. It has been tried elsewhere, however. North Korea comes to mind.” Some 40 minutes before the show, the president of the station, Arthur Rojas Emerson, called Casey to tell him the commentary had been pulled. Emerson said he was worried that the commentary could affect the financing of the station, which is publicly funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. It was also the case, as The New York Times reported, that Emerson had left journalism for several years to work in advertising and Smith had been a client. After the affair was publicized in a local newspaper column, another prominent local journalist took Casey’s censored commentary up with the PBS board and Emerson finally agreed to run the clip. He admitted to the Times it was a “mistake”, but he only had 20 minutes to make a decision. Casey is 70 years old and said that he was more ready to push back because of his age. He said he didn’t know whether he would have acted differently at 45, when it could have affected his career.

Blocked access

Blocking access to events, places and – more crucially – information is a way of government, lawmakers and others preventing journalists in the USA from covering their activities.

“Mapping Media Freedom has documented a growing list of incidents from across Europe and neighboring countries where journalists have been barred from reporting in the public interest. Though this survey looked at a small number of cases in the context of the American media market, we expect there were many more cases during the same period that were not reported by the media or located by our researchers,” Mapping Media Freedom’s Machlin said.

Reporters have recently been blocked from covering the airport protests over the travel ban in January 2017. Time journalist Charlotte Alter tweeted early on January 28, 2017, that reporters were asked to move from terminal 4 of JFK airport in New York because it was a “private space”.

Later that same day, the Council on American-Islamic relations barred a Breitbart News reporter, Neil Munro, from one of its press conferences where it criticized the travel ban.

On January 10, 2017, Texas Congressman Louie Gohmert (R) prevented a photojournalist from taking pictures of protesters during attorney general nominee Jeff Sessions’ confirmation hearings. Back in his home state of Texas in January, at about the same time, the Senate ruled to stop journalists wandering the floor and doing interviews. This was justified in the name of order and propriety but is seen by Texan reporters as a way of blocking access to local politicians.

On October 11, 2016, Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake (D) banned Kenneth Burns, a WYPR radio reporter, from her weekly press briefings based on allegations of “verbally and physically threatening behavior,” because she did not like his aggressive questioning at her small regular meetings with the press.

On January 12, 2017, The New York Times petitioned the New York State Executive Department for the right to see public records relating to a billion-dollar development scandal in Buffalo. The newspaper accused New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s (D) office of repeatedly stonewalling attempts to see the documents relating to a lobbyist and one of his aides.

Courthouse News Service has documented the challenges they have encountered getting information from court clerks about the scheduling of civil cases, including multi-million dollar lawsuits. The news service won a First Amendment case against the clerk in Manhattan’s state court in mid-December 2016, which granted them access to newly filed civil cases.

Press organizations were banned and their accreditation canceled arbitrarily

The service also launched a First Amendment case in Santa Ana, California, on January 24, 2017, against a similar policy brought in by Orange County’s county court clerk.

“Having access to this information is important for journalists, because without knowing what cases are being scheduled, they cannot cover them. And without general access, plaintiff’s lawyers are then able to leak cases to friendly news outlets,” Machlin said.

In Wyoming, the highway patrol records office said it was charging local newspaper, the Wyoming Tribune Eagle, $1,800 to fulfill a public records request put in on October 31, 2016, concerning state troopers deployed to the Dakota Access Pipeline protests.

“Imposing expensive fees to fulfill public records requests can deter investigative journalism, especially for publications already struggling for funding in a shifting media landscape,” Machlin said.

Reporters have been prevented from accessing information held by public bodies that relate to President Trump. On January 31, 2017, Newsweek national security correspondent Jeffrey Stein filed a federal complaint because he was not allowed to see documents that detail the process by which Trump aides are vetted. Stein argued, for example, that three of Trump’s children and Rex Tillerson, the new US Secretary of State, had extensive business ties to foreign nations that normally would raise clearance alarms. Stein explained that these requests sought “all records, including emails, about any steps taken to investigate or authorise (or discussions about potentially investigating or authorising) [15 individuals] for access to classified information.”

Other journalists reported they were not allowed to examine documents that Trump piled up on a table at a widely publicized press conference on January 11. Trump said the papers detailed how he was divesting himself from his business interests.

Blocked from Trump’s campaign and White House briefings

During the presidential election campaign, numerous press organizations were banned and their accreditation cancelled arbitrarily. Targeted organizations included Politico, BuzzFeed, the Huffington Post, Univision and the Des Moines Register. In June 2016, the Washington Post had its credentials canceled. Trump accused the Post of being “dishonest” and “phony” after the newspaper published an article critical of Trump’s comments about shootings at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

Trump declared The New York Times coverage of him “very dishonest” at a campaign rally in Columbus, Ohio, on August 1, 2016 and suggested he could take away their accreditation too.

By September 7, 2016, Trump and his team changed their tactics and lifted the ban on news organizations attending his rallies. However, this meant reporters attending could be penned and harangued by the crowds.

Since Trump won the election, CNN, in particular, has been targeted by the administration and questions from the network’s reporters have been refused at press conferences. In a further escalation of these tactics, an off-camera press conference on February 24, 2017, organized by press secretary Sean Spicer, was held without outlets such as The New York Times, Politico, CNN, BuzzFeed and the BBC. This exclusion of a good proportion of the media came despite Spicer’s previous assurances to White House journalists that bans, such as those imposed during the Trump campaign, would not happen once Trump was in the White House.

“Picking media outlets friendly to the country’s government is a tactic often deployed in illiberal democracies or by political parties on the far-right, like France’s Front National or Germany’s AfD. In the context of Mapping Media Freedom, the Trump administration and staffers have repeatedly and routinely threatened press freedom before and after the election,” Machlin said.

Intimidation

Intimidation is probably the most widely reported form of violation against press and media freedom. It takes various forms of offline and online harassment, including defamation, psychological abuse and sexual harassment.

“As we have seen increasingly in Europe, groundless, derogatory and corrosive comments by a country’s leaders – specifically in Hungary, Russia and the Balkans – have a tendency to permeate into law enforcement and local administrations, and undermine trust in media coverage among the general public. In addition, the use of pro-government media outlets to target journalists further undermines press freedom in some European countries. Though it remains to be seen whether this trend will continue at an alarming rate in the United States, it is certainly something for press freedom organizations to be alert to,” Index’s Patry said.

Much of the most prominent intimidation has come from both Trump and his aides during the presidential campaign, after his election and after his inauguration. This intimidation and harassment has also been mirrored by people who appear to be his supporters.

CASE STUDY: ALTERNATIVE FACTS

The argument over the size of the crowd at Trump’s inauguration dominated the first few days of Trump’s presidency. On a visit to the CIA headquarters on his first full day in office, he called journalists “the most dishonest people on earth” for saying that he had attacked the agency during his campaign. He also derided media reports, which showed far fewer attendees at his inauguration ceremony than the 1.5 million he claimed. Sean Spicer later held his first press conference in the briefing room of the West Wing, where he said that news organizations had deliberately under-estimated the size of the crowd, which was allegedly “the largest in history”, in order to sow disarray when Trump was trying to unify the country. Spicer threatened the media by saying the new administration would “hold the press accountable”. Kellyanne Conway appeared on the media the next day to say that Sean Spicer wasn’t lying when he claimed that Trump’s inauguration drew the largest crowd in history. Rather, he was presenting “alternative facts”.

Trump and supporters before the election

During Trump’s election campaign, journalists were routinely jeered and intimidated.

His campaign rallies frequently became places where the media and journalists in general were accused of being part of a broad conspiracy against him and his supporters. During a weekend in mid-August 2016 when his poll numbers were dropping, Trump went on the offensive against media bias. On Friday August 12, at a rally in Erie, Pennsylvania, Trump called journalists the “lowest form of humanity”. At a rally the following day in Fairfield, Connecticut, he declared: “I am not running against crooked Hillary Clinton, I’m running against the crooked media.” On Sunday August 14, he issued a series of tweets including claims that the biased media was affecting his poll ratings and that The New York Times wrote fiction.

In October 2016, when reporters uncovered stories about Trump’s abusive behavior towards women, his public attacks on the “mainstream media” intensified.

At one large rally of 15,000 supporters in Cincinnati, Ohio on October 14, Trump claimed that Hillary Clinton and her campaign “control the mainstream media” and use it “quite viciously”. The New York Times described how the organizers penned in journalists behind metal barriers at the same rally and then got the crowd to boo, insult and flip middle fingers at them.

Trump’s public personal attacks on journalists were virulent during the same period. He singled out Katy Tur, a reporter for NBC, at a November 2 rally in front of a crowd of 4,000 people. He blamed her for under-reporting the size of the crowd. It was the third time he had intimidated her at one of his rallies.

CASE STUDY: BERATING THE PRESS

Even before Trump was inaugurated, his supporters berated the press. Texas Congressman Randy Weber (R) tweeted on January 12 that Jim Acosta, CNN’s White House correspondent, should be fired and prohibited from press conferences. Kellyanne Conway also said in an interview on January 29 that journalists who showed bias against Trump during the campaign should be fired.

Trump after he won the presidency