9 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

Sokratis Giolia, an investigative journalist, was shot dead outside his home in Athens prior to publishing the results of an investigation into corruption.

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

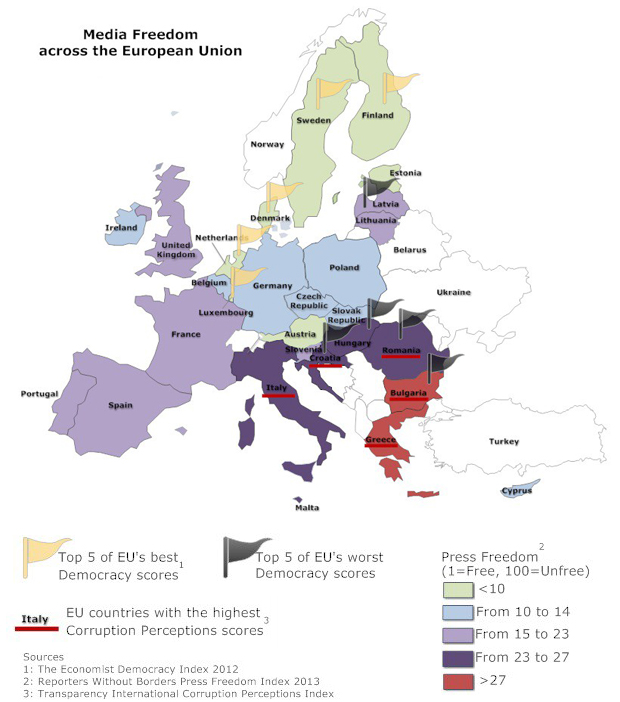

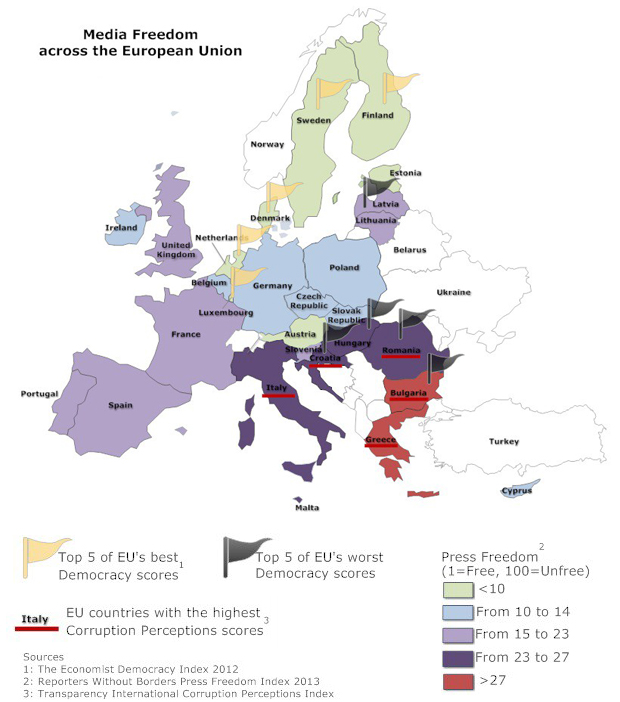

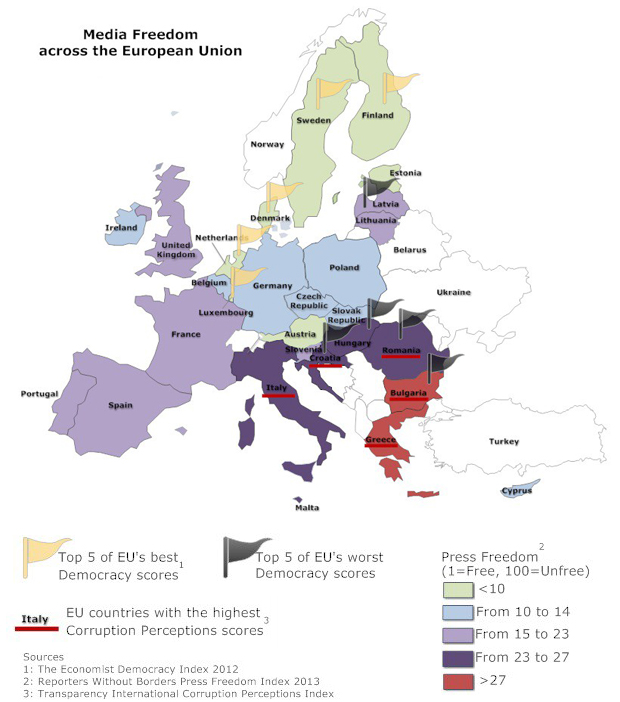

The main threats to media freedom and the work of journalists are from political pressure or pressure exerted by the police, to non-legal means, such as violence and impunity. There have been instances where political pressure against journalists has led to self-censorship in a number of European Union countries. This pressure can manifest itself in a number of ways, from political pressure to influence editorial decisions or block journalists from promotion in state broadcasters to police or security service interventions into media investigations on political corruption.

The European Commission now has a clear competency to protect media freedom and should reflect on how it can deal with political interference in the national media of member states. As the heads of state or government of the EU member states have wider decision-making powers at the European Council this gives a forum for influence and negotiation, but this may also act as a brake on Commission action, thereby protecting media freedom.

Italy presents perhaps the most egregious example of political interference undermining media freedom in a EU member state. Former premier Silvio Berlusconi has used his influence over the media to secure personal political gain on a number of occasions. In 2009 he was thought to be behind RAI decision to stop broadcasting Annozero, a political programme that regularly criticised the government. In the lead up to the 2010 regional elections, Berlusconi’s party pushed through rules which effectively meant that state broadcasters had to either feature over 30 political parties on their talk shows or lose their prime time slots. Notably, Italian state broadcaster RAI refused to show adverts for the Swedish film Videocracy because it claimed the adverts were “offensive” to Silvio Berlusconi.

Under the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Hungary has seen considerable political interference in the media. In September 2011, popular liberal political radio station “Klubrádió” lost its licence following a decision by the Media Authority that experts believed was motivated by political considerations. The licence was reinstated on appeal. In December 2011, state TV journalists went on hunger strike after the face of a prominent Supreme Court judge was airbrushed out of a broadcast by state-run TV channel MTV. Journalists have complained that editors regularly cave into political interference. Germany has also seen instances of political interference in the public and private media. In 2009, the chief editor of German public service broadcaster ZDF, Nikolaus Brender, saw his contract terminated in controversial circumstances. Despite being a well-respected and experienced journalist, Brender’s suitability for the job was questioned by politicians on the channel’s executive board, many of whom represented the ruling Christian Democratic Union. It was decided his contract should not be renewed, a move widely criticised by domestic media, the International Press Institute and Reporters Without Borders, the latter arguing the move was “motivated by party politics” which, it argued, was “a blatant violation of the principle of independence of public broadcasters”. In 2011, the editor of Germany’s (and Europe’s) biggest selling newspaper, Bild, received a voicemail from President Christian Wulff, who threatened “war” on the tabloid if it reported on an unusual personal loan he received.

Police interference in the work of journalists, bloggers and media workers is a concern: there is evidence of police interference across a number of countries, including France, Ireland and Bulgaria. In France, the security services engaged in illegal activity when they spied on Le Monde journalist Gerard Davet during his investigation into Liliane Bettencourt’s alleged illegal financing of President Sarkozy’s political party. In 2011, France’s head of domestic intelligence, Bernard Squarcini, was charged with “illegally collecting data and violating the confidentiality” of the journalists’ sources. In Bulgaria, journalist Boris Mitov was summoned on two occasions to the Sofia City Prosecutor’s office in April 2013 for leaking “state secrets” after he reported a potential conflict of interest within the prosecution team. Of particular concern is Ireland, which has legislation that outlaws contact between ordinary police officers and the media. Clause 62 of the 2005 Garda Siochána Act makes provision for police officers who speak to journalists without authorisation from senior officers to be dismissed, fined up to €75,000 or even face seven years in prison. This law has the potential to criminalise public interest police whistleblowing.[1]

It is worth noting that after whistleblower Edward Snowden attempted to claim asylum in a number of European countries, including Austria, Finland, Germany, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, the governments of all of these countries stated that he needed to be present in the country to claim asylum. Others went further. Poland’s Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski posted the following statement on Twitter: “I will not give a positive recommendation”, while German Foreign minister Guido Westerwelle said although Germany would review the asylum request “according to the law”, he “could not imagine” that it would be approved. The failure of the EU’s member states to give shelter to Snowden when so much of his work was clearly in the public interest within the European Union shows the scale of the weakness within Europe to stand up for freedom of expression.

Deaths, threats and violence against journalists and media workers

No EU country features in Reporters Without Borders’ 2013 list of deadliest countries for journalists. But since 2010, three journalists have been killed within the European Union. In Bulgaria in January 2010 , a gunman shot and killed Boris Nikolov Tsankov, a journalist who reported on the local mafia, as he walked down a crowded street. The gunman escaped on foot. In Greece, Sokratis Giolia, an investigative journalist, was shot dead outside his home in Athens prior to publishing the results of an investigation into corruption. In Latvia, media owner Grigorijs Nemcovs was the victim of an apparent contract killing, which Reporters Without Borders claims appeared to be carefully planned and executed.103 Nemcovs was also a political activist and deputy mayor, and his newspaper, Million, was renowned for its investigative coverage of political and local government corruption and mismanagement.

While it is rare for journalists to be killed within the EU, the Council of Europe has drawn attention to the fact that violence against journalists does occur in EU countries, particularly in south eastern Europe, including in Greece, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania.[2] The South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO) has raised concerns over police violence against journalists covering political protests in many parts of south eastern Europe, particularly in Romania and Greece.

[1] There is an official whistleblowing mechanism instituted by the law, but it is not independent of the police.

[2] William Horsley for rapporteur Mats Johansson, ‘The State of Media Freedom in Europe’, Committee on Culture, Science, Education and Media, Council of Europe (18 June 2012).

27 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Since the entering into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, which made the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights legally binding, the EU has gained an important tool to deal with breaches of fundamental rights.

The Lisbon Treaty also laid the foundation for the EU as a whole to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights. Amendments to the Treaty on European Union (TEU) introduced by the Lisbon Treaty (Article 7) gave new powers to the EU to deal with state who breach fundamental rights.

The EU’s accession to the ECHR, which is likely to take place prior to the European elections in June 2014, will help reinforce the power of the ECHR within the EU and in its external policy. Commission lawyers believe that the Lisbon Treaty has made little impact, as the Commission has always been required to assess whether legislation is compatible with the ECHR (through impact assessments and the fundamental rights checklist) and because all EU member states are also signatories to the Convention.[1] Yet external legal experts believe that accession could have a real and significant impact on human rights and freedom of expression internally within the EU as the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) will be able to rule on cases and apply European Court of Human Rights jurisprudence directly. Currently, CJEU cases take approximately one year to process, whereas cases submitted to the ECHR can take up to 12 years. Therefore, it is likely that a larger number of freedom of expression cases will be heard and resolved more quickly at the CJEU, with a potential positive impact on justice and the implementation of rights in the EU.[2]

The Commission will also build upon Council of Europe standards when drafting laws and agreements that apply to the 28 member states. Now that these rights are legally binding and are subject to formal assessment, this may serve to strengthen rights within the Union.[3] For the first time, a Commissioner assumes responsibility for the promotion of fundamental rights; all members of the European Commission must pledge before the Court of Justice of the European Union that they will uphold the Charter.

The Lisbon Treaty also provides for a mechanism that allows European Union institutions to take action, whether there is a clear risk of a “serious breach” or a “serious and persistent breach”, by a member state in their respect for human rights in Article 7 of the Treaty of the European Union. This is an important step forward, which allows for the suspension of voting rights of any government representative found to be in breach of Article 7 at the Council of the European Union. The mechanism is described as a “last resort”, but does potentially provide leverage where states fail to uphold their duty to protect freedom of expression.

Yet within the EU, some remained concerned that the use of Article 7 of the Treaty, while a step forward, is limited in its effectiveness because it is only used as a last resort. Among those who argued this were Commissioner Reding, who called the mechanism the “nuclear option” during a speech addressing the “Copenhagen Dilemma” (the problem of holding states to the human rights commitments they make when they join). In March 2013, in a joint letter sent to Commission President Barroso, the foreign ministers of the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark and Germany called for the creation of a mechanism to safeguard principles such as democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The letter argued there should be an option to cut EU funding for countries that breach their human rights commitments.

It is clear that there is a fair amount of thinking going on internally within the Commission on what to do when member states fail to abide by “European values”. Commission President Barroso raised this in his State of the Union address in September 2012, explicitly calling for “a better developed set of instruments” to deal with threats to these rights.

This thinking has been triggered by recent events in Hungary and Italy, as well as the ongoing issue of corruption in Bulgaria and Romania, which points to a wider problem the EU faces through enlargement: new countries may easily fall short of both their European and international commitments.

Full report PDF: Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Footnotes

[1] Off-record interview with a European Commission lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).

[2] Interview with Prof. Andrea Biondi, King’s College London, 22 April 2013.

[3] Interview with lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).

12 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom Reports, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Index Reports, News and features, Politics and Society

As Ukraine experiences ongoing protests over lack of European integration, Index’ new report looks at the EU’s relationship with freedom of expression (Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / Demotix)

Index on Censorship’s policy paper, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression, looks at freedom of expression both within the European Union’s 28 member states, which with over 500 million people account for about a quarter of total global economic output, but also how this union defends freedom of expression in the wider world. States that are members of the European Union are supposed to share “European values”, which include a commitment to freedom of expression. However, the way these common values are put into practice vary: some of the world’s best places for free expression are within the European Union – Finland, Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden – while other countries such as Italy, Hungary, Greece and Romania lag behind new and emerging global democracies.

This paper explores freedom of expression, both at the EU level on how the Commission and institutions of the EU protect this important right, but also across the member states. Firstly, the paper will explore where the EU and its member states protect freedom of expression internally and where more needs to be done. The second section will look at how the EU projects and defends freedom of expression to partner countries and institutions. The paper will explore the institutions and instruments used by the EU and its member states to protect this fundamental right and how they have developed in recent years, as well as the impact of these institutions and instruments.

Outwardly, a commitment to freedom of expression is one of the principle characteristics of the European Union. Every European Union member state has ratified the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR); the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and has committed to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To complement this, the Treaty of Lisbon has made the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights legally binding which means that the EU institutions and member states (if they act within the scope of the EU law) must act in compliance with the rights and principles of the Charter. The EU has also said it will accede to the ECHR. Yet, even with these commitments and this powerful framework for defending freedom of expression, has the EU in practice upheld freedom of expression evenly across the European Union and outside with third parties, and is it doing enough to protect this universal right?

Within the European Commission, there has been considerable analysis about what should be done when member states fail to abide by “European values”, Commission President Barroso raised this in his State of the Union address in September 2012, explicitly calling for “a better developed set of instruments” to deal with threats to these perceived values and the rights that accompany them. With threats to freedom of expression increasing, it is essential that this is taken up by the Commission sooner rather than later.

To date, most EU member states have failed to repeal criminal sanctions for defamation, with only Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland and the UK having done so. The parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe called on states to repeal criminal sanctions for libel in 2007, since then little action has been taken by EU member states. There also remain significant issues in the field of privacy law and freedom of information across the EU.

While the European Commission has in the past tended to view its competencies in the field of media regulation as limited, due to the introduction of the Charter of Fundamental Rights into EU primary law, the Commission is looking at a possible enhancement of its role in this area.

With media plurality limited across Europe and in fact potentially threatened by the convergence of media across media both online and off (and the internet being the most concentrated media market), the Commission must take an early view on whether it wishes to intervene more fully in this field to uphold the values the EU has outlined. Political threats against media workers are too commonplace and risks to whistleblowers have increased as demonstrated by the lack of support given by EU member states to whistleblower Edward Snowden. That the EU and its member states have so clearly failed one of the most significant whistleblowers of our era is indicative of the scale of the challenge to freedom of expression within the European Union.

The EU and its member states have made a number of positive commitments to protect online freedom, including the EU’s positioning at WCIT, the freedom of expression guidelines and the No-Disconnect strategy helping the EU to strengthen its external polices around promoting digital freedom. These commitments have challenged top-down internet governance models, supported the multistakeholder approach, protected human rights defenders who use the internet and social media in their work, limited takedown requests, filters and others forms of censorship. But for the EU to have a strong and coherent impact at the global level, it now needs to develop a clear and comprehensive digital freedom strategy. For too long, the EU has been slow to prioritise digital rights, placing the emphasis on digital competitiveness instead. It has also been the case that positive external initiatives have been undermined by contradictory internal policies, or a contradiction of fundamental values, at the EU and member state level. The revelations made by Edward Snowden show that EU member states are violating universal human rights through mass surveillance.

The Union must ensure that member states are called upon to address their adherence to fundamental principles at the next European Council meeting. The European Council should also address concerns that external government surveillance efforts like the US National Security Agency’s Prism programme are undermining EU citizens’ rights to privacy and free expression. A comprehensive overarching digital freedom strategy would help ensure coherent EU policies and priorities on freedom of expression and further strengthen the EU’s influence on crucial debates around global internet governance and digital freedom. With the next two years of ITU negotiations crucial, it’s important the EU takes this strategy forward urgently.

While the European Commission has in the past tended to view its competencies in the field of media regulation as limited, due to the introduction of the Charter of Fundamental Rights into EU primary law, the Commission is looking at a possible enhancement of its role in this area.

With media plurality limited across Europe and in fact potentially threatened by the convergence of media across media both online and off (and the internet being the most concentrated media market), the Commission must take an early view on whether it wishes to intervene more fully in this field to uphold the values the EU has outlined.

Political threats against media workers are too commonplace and risks to whistleblowers have increased as demonstrated by the lack of support given by EU member states to whistleblower Edward Snowden. That the EU and its member states have so clearly failed one of the most significant whistleblowers of our era is indicative of the scale of the challenge to freedom of expression within the European Union.

Where the EU acts with a common approach among the member states, it has significant leverage to help promote and defend freedom of expression globally. To develop a more common approach, since the Lisbon Treaty, the EU has enhanced its set of policies, instruments and institutions to promote human rights externally, with new resources to do so. Enlargement has proved the most effective tool to promote freedom of expression with, on the whole, significant improvements in the adherence to the principles of freedom of expression in countries that have joined the EU or where enlargement is a real prospect. That this respect for human rights is a condition of accession to the EU shows that conditionality can be effective. Whereas the eastern neighbourhood has benefitted from the real prospect of accession (for some countries), in its southern neighbourhood, the EU has failed to promote freedom of expression by placing security interests first and also by failing to react quickly enough to the transitions in its southern neighbourhood following the events of the Arab Spring. The new strategy for this region is welcome and may better protect freedom of expression, but with Egypt in crisis, the EU may have acted too late. The EU must assess the effectiveness of some of its foreign policy instruments, in particular the dialogues for particular countries such as China.

The freedom of expression guidelines provide an excellent opportunity to reassess the criteria for how the EU engages with third party countries. Strong freedom of expression guidelines will allow the EU to better benchmark the effectiveness of its human rights dialogues. The guidelines will also reemphasise the importance of the EU, ensuring that the right to freedom of expression is protected within the EU and its member states. Otherwise, the ability of the EU to influence external partners will be limited.

Headline recommendations

• After recent revelations about mass state surveillance the EU must develop a roadmap that puts in place strong safeguards to ensure narrow targeted surveillance with oversight not mass population surveillance and must also recommit to protect whistle-blowers

• The European Commission needs to put in place controls so that EU directives cannot be used for the retention of data that makes mass population surveillance feasible

• The EU has expanded its powers to deal with human rights violations, but is reluctant to use these powers even during a crisis within a member state. The EU must establish clear red lines where it will act collectively to protect freedom of expression in a member state

• Defamation should be decriminalised across the EU

• The EU must not act to encourage the statutory regulation of the print media but instead promote tough independent regulation

• Politicians from across the EU must stop directly interfering in the workings of the independent media

• The EU suffers from a serious credibility gap in its near neighbourhood – the realpolitik of the past that neglected human rights must be replaced with a coherent, unified Union position on how to promote human rights

Recommendations

- The EU has expanded its powers to deal with human rights violations, but is reluctant to use these powers even during a crisis within a member state. The EU must establish clear red lines where it will act collectively to protect freedom of expression in a member state

- The EU should cut funding for member states that cross the red lines and breach their human rights commitments

Libel, privacy and insult

- Defamation should be decriminalised in line with the recommendations of the Council of Europe parliamentary assembly, and the UN and OSCE’s special rapporteurs on freedom of expression.

- Insult laws that criminalise insult to national symbols should be repealed

Freedom of information

- To better protect freedom of information, all EU member states should sign up to the Council of Europe Convention on Access to Official Documents

- Not all EU institutions, offices, bodies and agencies are acting on their freedom of information commitments. More must be done by the Commission to protect freedom of information

Media freedom & plurality

- The EU must revisit its competencies in the area of media regulation in order to prevent the most egregious breaches of the right to freedom of expression in particular the situations that arose in Italy and Hungary

- The EU must argue against statutory regulation of the print media and argue for independent self-regulation where media bandwidth is no longer limited by spectrum and other considerations

- Member states must not allow political interference or considerations of “political balance” into the workings of the media, where this happens the EU should be considered competent to act to protect media freedom and pluralism at a state level

- The EU is not doing enough to protect whistleblowers. National states must do more to protect journalists from threats of violence and intimidation

Digital

- The Commission must prepare a roadmap for collective action against mass state surveillance

- The EU is right to argue against top-down state control over internet governance it must find more natural allies for this position globally

- The Commission should proceed with a Directive that sets out the criteria takedown requests must meet and outline a process that protects anonymous whistle-blowers and intermediaries from vexatious claims

The EU and freedom of expression in the world

- The EU suffers from a credibility issue in its southern neighbourhood. To repair its standing in the wider world, the EU and its member states must not downgrade the importance of human rights in any bilateral or multilateral relationship

- The EU’s EEAS Freedom of Expression guidelines are welcome. To be effective, they need to focus on the right to freedom of expression for ordinary citizens and not just media actors

- The guidelines need to become the focus for negotiations with external countries, rather than the under-achieving human rights dialogues

- With criticism of the effectiveness of the human rights dialogues, the EU should look again at how the dialogues fit into the overall strategy of the Union and its member states

The European Union contains some of the world’s strongest defenders of freedom of expression, but also a significant number of member states who fail to meet their European and international commitments. To deal with this, in recent years, the European Union’s member states have made new commitments to better protect freedom of expression. The new competency of the European Court of Justice to uphold the values enshrined in the European Convention of Human Rights will provide a welcome alternative forum to the increasingly deluged European Court of Human Rights. This could have significant implications for freedom of expression within the EU. Internally within the EU there is still much that could be done to improve freedom of expression. It is welcome that that the EU and its member states have made a number of positive commitments to protect online freedom, with new action on vexatious takedown notices and coordinated action to protect the multistakeholder model of internet governance. Increasing Commission concern over media plurality may also be positive in the future.

Yet there are a number of areas where the EU must do more. The decriminalisation of defamation across Europe should be a focal point for European action in line with the Council of Europe’s recommendations. National insult laws should be repealed. The Commission should not intervene to increase its powers over national media regulators, but should act where it has clear competencies, in particular to prevent media monopolies and to help deal with conflict of interests between politicians and state broadcasters. Most importantly, discussions of mass population surveillance at the European Council in October must be followed by a roadmap outlining how the EU will collectively take action on this issue. Without internal reform to strengthen protections for freedom of expression, the EU will not enjoy the leverage it should to promote freedom of expression externally to partner countries. While the External Action Service freedom of expression guidelines are welcome, they must be impressed upon member countries as a benchmark for reform.

Externally, the EU has failed to deliver on the significant leverage it could have as the world’s largest trading block. Where the EU has acted in concert, with clear aims and objectives for partner countries, such as during the process of enlargement, it has had a big impact on improving and protecting freedom of expression. Elsewhere, the EU has fallen short, particularly in its southern neighbourhood and in its relationship with China, where the EU has continued human rights dialogues that have failed to be effective.

New commitments and new instruments post-Lisbon may better protect freedom of expression in the EU and externally. Yet, as the Snowden revelations show, the EU and its member states must do significantly more to deliver upon the commitments that have been agreed.

Full report PDF: Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

This article was posted on 12 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 2013 | Campaigns, Press Releases

Nearly 40 free speech groups from across the world are calling on the European Union to take a stand against mass surveillance by the US and other governments. The groups have joined a petition organised by Index on Censorship, which has already been signed by over 3,000 people. Celebrities, artists, activists and politicians who have supported the petition include writer and actor Stephen Fry, activists Bianca Jagger and Peter Tatchell, writer AL Kennedy, artist Anish Kapoor, blogger Cory Doctorow and Icelandic politician Kolbrún Halldórsdóttir.

Actor and writer Stephen Fry said:

‘Privacy and freedom from state intrusion is important for everyone. You can’t just scream “terrorism” and use it as an excuse for Orwellian snooping.’

Chief Executive of Index on Censorship Kirsty Hughes said:

‘A few of Europe’s leaders have voiced their concerns about the NSA’s activities but none have acted. We are demanding all EU leaders condemn mass surveillance and commit to joint action stop it. People from around the world are signing this petition because mass surveillance invades their privacy and threatens their right to free speech.’

As well as calling for Europe’s leaders to put on the record their opposition to mass surveillance, the petition demands that mass surveillance is on the agenda at the next European Council Summit in October.

The petition is at: http://chn.ge/1c2L7Ty and is being promoted on social media with the hashtag #dontspyonme

The petition is supported by Index on Censorship, Amnesty International, English PEN, Article 19, Privacy International, Open Rights Group, Liberty UK, Reporters Without Borders, European Federation of Journalists, International Federation of Journalists, PEN International, PEN Canada, PEN Portugal, Electronic Frontier Foundation, PEN Emergency Fund, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, National Union of Somali Journalists, Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, Catalan PEN, Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ) – Malaysia, Belarusian Human Rights House, South East European Network for Professionalization of Media, International Partnership for Human Rights, Russian PEN Centre, Association of European Journalists, Foundation for the Development of Democratic Initiatives – Poland, Independent Journalism Center – Moldova, Alliance of Independent Journalists – Indonesia, PEN Quebec, Fundacja Panoptykon – Poland, International Media Support, Human Rights Monitoring Institute – Lithuania, Warsaw Branch, Association of Polish Journalists, The Steering Committee of the Civil Society Forum of the Eastern Partnership, South African Centre of PEN International, Estonian Human Rights Centre, Vikes Foundation, Finland

For further information, please contact [email protected]