3 Feb 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Index Reports, News and features, Turkey Reports

Pressure on Europe’s journalists as they do their jobs saw no let up during the fourth quarter of 2015, according to a survey of verified incidents of violations reported to Index on Censorship’s project Mapping Media Freedom.

Between 1 October and 31 December 2015, Mapping Media Freedom‘s network of 19 correspondents verified 232 reports that were submitted to the database. Each report is reviewed for factual accuracy and confirmed with local sources before an incident is publicly available on the map. The platform — a joint undertaking with the European Federation of Journalists and Reporters Without Borders and partially funded by the European Commission — covers 40 countries, including all EU member states, Albania, Belarus, Bosnia, Iceland, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Norway, Russia, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine. Since it was launched in May 2014, the map has recorded over 1,300 violations of media freedom.

During the fourth quarter of 2015: 518 media jobs were lost; two media workers reporting on the Syrian conflict were killed in Turkey; 40 reports of physical assaults on media professionals were confirmed; media workers were detained in 26 cases with criminal charges filed in 11 cases; media professionals were blocked from covering a story in 55 verified incidents; and journalists were subject to public denigration in 22 of the verified reports.

The full report is available at Mapping Media Freedom and in PDF.

20 Nov 2015 | Croatia, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features

Croatian prime minister Zoran Milanović. Original image by SDP Hrvatske

A worrying escalation of attacks on the media in Croatia has been recorded by the Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project in the last three months. Since 1 September there have been 13 attacks, compared with 3 in the same period last year.

In August, we reported an increase in media violations in Croatia. Deaths, physical assaults and intimidation had been plaguing the Croatian media for months. Increasing violence is still undermining media freedom in Croatia.

Hannah Machlin, Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project officer, said: “The increasing amount of violence against Croatian journalists is quite alarming. In reaction to the migrant crisis, there’s been a particularly high number of cases on the Hungarian/Croatia border.”

The Croatian constitution guarantees freedom of expression and the press, and “these rights are generally respected in practice”. Freedom House does, however, acknowledge that journalists face political pressure, intimidation and the “occasional” attack. According to Freedom House, Croatia has been a “free” country for some years.

Below, Index on Censorship details some of the worst cases from Croatia since September.

Overall attacks, including violence, intimidation, loss of employment and censorship of work

1. Media workers assaulted by police at Serbian border

In early October, Croatia opened its border with Serbia, easing one of the main areas for congestion for refugees trying to make their way north. On 19 October, Mapping Media Freedom recorded that media workers were harassed and assaulted by Croatian police on the border near the Bapska-Berkasovo crossing. Regional N1 television reported that the Croatian police had also confiscated the journalists’ equipment.

“When they moved against me, I shouted that I was an AFP photojournalist and that their colleagues had checked my ID this morning,” Andreja Isakovic told N1. “They asked me to hand over the cards. One of them ran towards me, caught up with me and threw me into the mud. They took away my cameras in a savage manner and threw them into an orchard on the Croatian side, so I could not reach them. They did the same to my colleague from England.”

2. Greek journalists attacked by masked assailants

In mid-October, two Greek journalists, George Stasinopoulos and Dionisis Verveles, were attacked by unidentified individuals while walking near a sporting event in Zagreb. Two men wearing face masks stopped the journalists on a street, asking them to identify themselves and their origin. When the two colleagues attempted to run away, they were attacked.

One journalist was beaten and the other was threatened by one of the assailants who was brandishing a knife. When the journalists began shouting that they were members of the press, the attackers fled the scene.

3. Prime minister’s father threatens journalist

Velimir Bujanec, host of the controversial TV show Bujica, was verbally assaulted by Stipe Milanović, father of Croatian prime minister, Zoran Milanović. Gordan Malic, a local freelance investigative journalist based in Croatia, was also threatened. Around noon on 3 October in a coffee bar in the center of Zagreb, Stipe Milanović allegedly said that “Bujanec and Gordan Malic should be beaten up”. There were three witnesses to his comment.

Bujanec reported to the media and posted it on Facebook. After speaking with his lawyer, he also reported the incident to the police and is now reportedly pressing charges against Milanović for verbal assaults and threats.

4. Journalist’s car tires slashed

Suzana Trninic is a journalist with the Serbian television broadcaster B92. On 24 September, while travelling to a media festival in Rovinj with Belgrade license plates on her car, she and her team stopped for coffee at a petrol station in Grobnik. When they returned, one of the car’s tires had been slashed.

There was visible sticker press on the vehicle, Trninic said. She did not want to report the incident to the police and media on the day as she did not want to distract from the ongoing border crisis between Serbia and Croatia.

Trninic believes the incident is connected with her being a Serbian journalist.

5. Asylum seeker attacks TV crew

“I’ll kill you!” yelled the assailant as a stone hit the cameraman. Click image for video. Credit: Večernji.hr

On Thursday 17 September 2015, an asylum seeker from Kosovo began shouting threats and then threw a brick at the TV Mreza crew reporting at Hotel Porin. One cameraman was injured. The assailant was immediately restrained by other journalists until riot police arrived and detained him.

Hotel Porin is both a reception and registration centre where asylum applications are completed, including fingerprinting and medical examinations. As Croatian media has reported, almost all refugees are polite and grateful and all have the right to leave the hotel and walk around Dugavama.

Details of attacks on the media across Europe can be found at Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom website. Reports to the map are crowdsourced and then fact-checked by the Index team.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

6 Oct 2015

6 October 2015

This report is also available in PDF format

Journalists and media workers in Turkey, Hungary and the Balkans are facing increased hostility as they do their jobs, according to a survey of the verified incidents reported to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project.

|

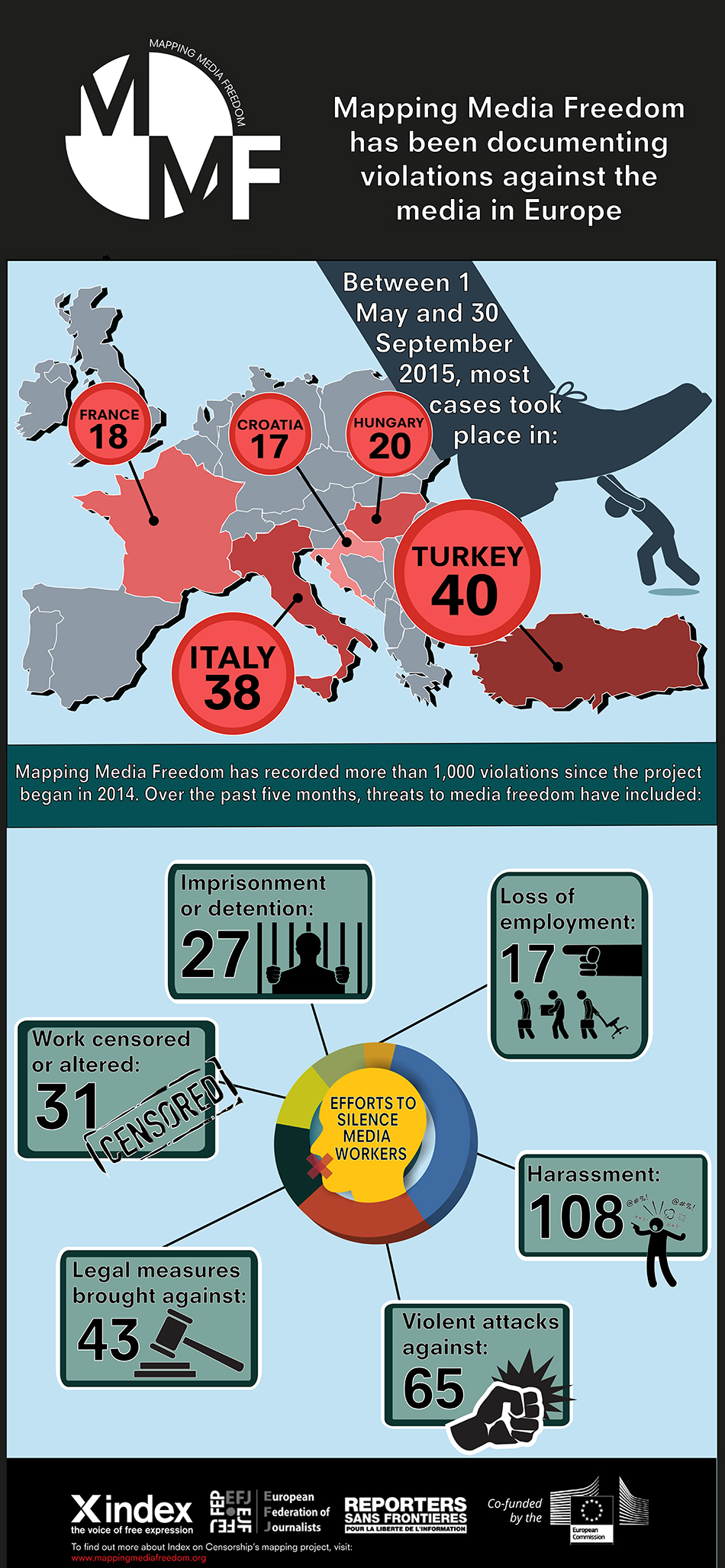

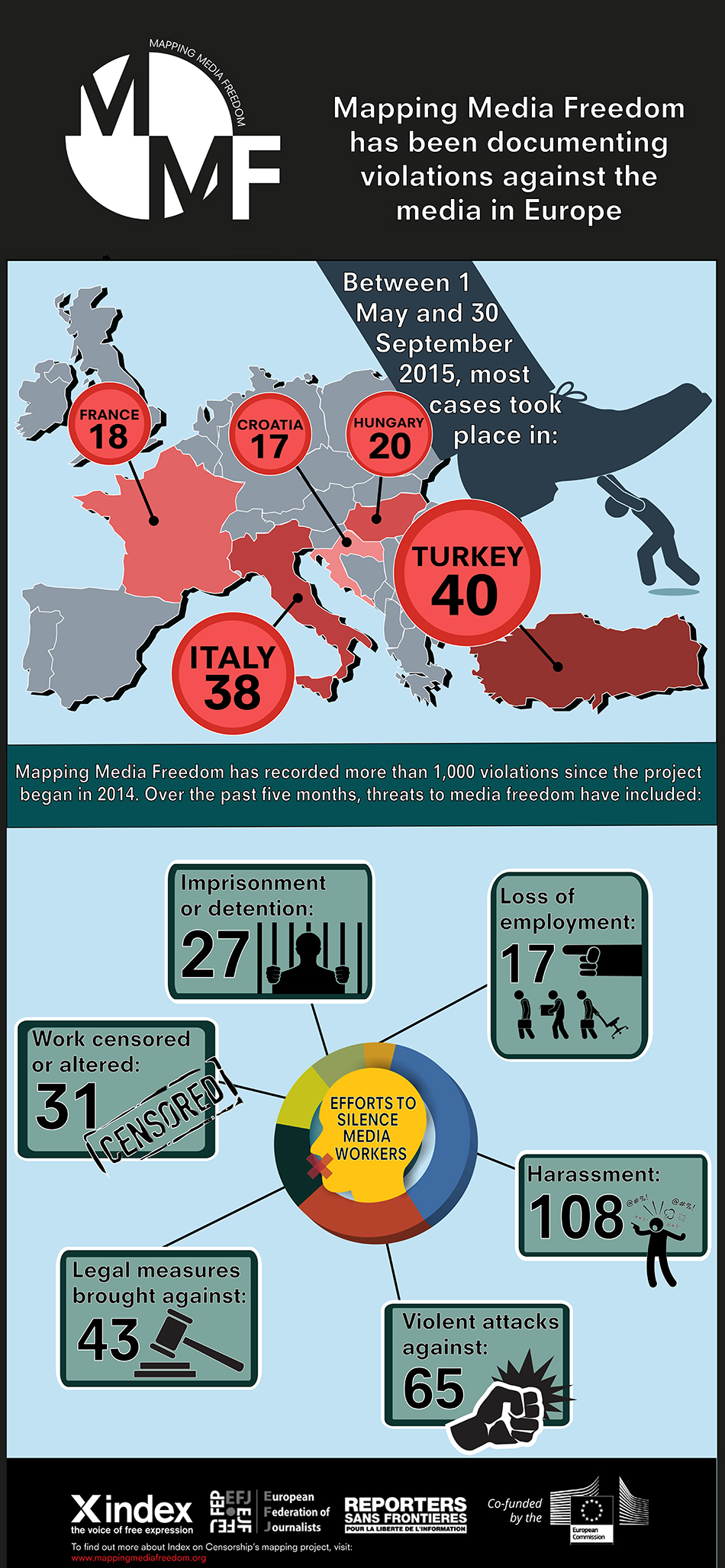

| Since May 2014, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project has been documenting media violations throughout the European Union, including candidate and neighbouring countries. The project is an interactive platform that allows the reporting, mapping and monitoring of threats to media freedom. Mapping Media Freedom is run in partnership with the European Federation of Journalists and Reporters Without Borders, and is partially funded by the European Commission. The over 1,000 violations that have been recorded so far have exposed the dangers faced by journalists across the continent. The project expanded in September to cover Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, in reaction to new draconian measures and violence in the region. New partner affiliations have also been formed in order to increase support for media workers, including with Media Legal Defence Initiative, Human Right House Kiev and European Youth Press.

Between 1 May and 30 September 2015, 285 violations of media freedom have been recorded and verified. More than a third of the incidents – 108 cases – included harassment against journalists. |

|

| Cases include that of Saša Leković, the president of the Croatian Association of Journalists, who received a parcel containing a death threat, as well as a number of threats on social media. And in Italy, founders of local news site Infonodo.org were threatened by the former Mayor of Seregno, Giacinto Mariani. While standing in front of the town’s city hall, Mariani told camera crews: “These people must die.”

As we noted in our May 2015 report, Turkey is, again, the country that has received the most reports of media violations. In the run up to the country’s general elections in November, press freedom continues to deteriorate, with multiple cases reported of media organisations being raided and journalists being detained, imprisoned or deported.

The map has also indicated an increase in violence against journalists, particularly within Turkey, Hungary and the Balkans.

The five countries with the most verified reports are: Turkey (40), Italy (38), Hungary (20), France (18) and Croatia (17). The successor nations to the former Yugoslavia (Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Kosovo and Slovenia) had a combined total of 55 out of 285 incidents that have been verified by regional correspondents.

Hannah Machlin, Index on Censorship’s project officer for the Mapping Media Freedom project says: “Independent media outlets in the region, particularly in Russia, have become increasingly under threat for multiple reasons, from restrictive government policies to ‘soft-censorship’ techniques, such as the withdrawal of advertising contracts. Expanding the project will further our understanding of these threats through specific case studies and enable us to support media outlets under pressure.” |

Countries with the most reports

These are the five countries with the most incidents reported to mappingmediafreedom.org between May and 30 September 2015. The project includes all European Union member states, candidates for entry and neighbouring countries, Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. Cases cited are the most recent verified reports for that country. |

|

|

Turkey 40 reports

Turkish police raided the offices of Koza-Ipek Holding, which owns five independent media outlets: dailies Bugun and Millet, TV stations Bugun TV and Kanalturk and news website BGNNews |

|

|

|

Italy 38 reports

Freelance journalist Gennaro Teddesco’s car was set on fire in the town of San Giovanni Rotondo. Teddesco and others have recently been targeted for their investigations into local business practices and criminal behaviour |

|

|

|

Hungary 20 reports

A camera crew for Serbian public television was beaten by Hungarian police at the Serbian border while covering a violent clash between security forces and refugees trying to cross into Hungary |

|

|

|

France 18 reports

An investigative documentary on French President François Hollande and former President Nicolas Sarkozy was cancelled 15 days before it was due to air on broadcaster Canal+ |

|

|

|

Croatia 17 reports

Two armed assailants burst into the office of weekly newspaper Hrvatski Tjednik, injuring the graphic designer, damaging the offices and stealing several thousand kuna |

|

Case Studies

Across Europe, censorship and media violations take different forms depending on the country. These two reports are expanded from incidents that were logged to the map. Read more in-depth reporting. |

Turkey

Vice news journalists detained on terror charges

When three journalists working for Vice News were arrested on terror charges in Turkey at the end of August, Index joined other organisations to launch an emergency campaign calling for the release of the reporters, while putting them in touch with free expression lawyers in Turkey. We wrote to the UK Foreign Office the following day to demand the British government step up pressure on Turkish authorities over the arrest of the journalists. The two British journalists remained behind bars for 11 days, but their Iraqi colleague Mohammed Rasool is still being detained pending trial. Rasool worked as a fixer for the two other journalists; he acted as a translator, a local guide and helped arrange the story. The role of a fixer is vital not only to sourcing information on a granular level, but also for helping ensure the safety of the foreign journalists.

Rasool has been charged with “knowingly and willingly helping an organised criminal group without being part of the hierarchical structure of the group”, a provision increasingly being invoked against journalists, especially Kurds and those associated with the political left in Turkey. The prosecution authorities have indicated that they wish to examine the contents of an allegedly encrypted file on Rasool’s computer before making this decision.

Rasool denies having any incriminating encrypted material on his computer. We are currently working with VICE, Turkish lawyers and other organisations to secure his release. |

|

Russia/Россия

Kommersant website editor-in-chief fired after interview with opposition figure

Editor-in-chief of Kommersant website, Andrey Konyakhin, was fired after a public interview with prominent opposition figure, Aleksei Navalny. On 4 September 2015, the interview was broadcasted through Kommersant-FM radio, and the transcript was published on the website. In an interview with RBC news portal, several Kommersant journalists claim it’s possible the interview is the reason for Konyakhin’s dismissal, noting large edits were made to the text after the original went live. The interview was dedicated to the opposition’s electoral campaign for the 13 September regional elections, and to an opposition rally scheduled for 20 September. Over the course of the interview, Navalny also claimed that president Vladimir Putin was involved with the crash of flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine.

“Navalny saying such notions in a live broadcast is not that important, but the fact it was shared on the website, caused the scandal within the publishing house”, a source from Kommersant stressed.

There is no official explanation for the dismissal so far. Konyakhin has also not commented on the incident.

The edited version of the interview can still be found on the Kommersant website. There is the following disclaimer under the material: “Published in abridged form. Under the recommendation of the Legal Department, the editorial office decided to delete a part of the interview which could be considered as violation of the Article 4 of the Law No. 2124-1 from 27.12.1991 “On mass media”.” |

|

This report is also available in PDF format

| A note on methodology: Mapping Media Freedom is based on crowd-sourced information. The number of violations does not reflect the severity of the cases reported to the map. |

Co-Funded by the

|

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

Today the bulk of the media in the Balkans has “been bought by people with no history in, or understanding of, the media business; they promote narrow interests of their owners or new political elites; sometimes without even pretence of objectivity,” said Kemal Kurspahic, former editor of Oslobodjenje, an independent newspaper published during the Bosnian war, reflecting on the development of media freedom over the past 25 years.

While in the 1990s nationalism was the order of the day, today a whole host of challenges – including murky media ownership – face independent journalists across the region. The Balkan Investigative Journalism Network in Serbia, for instance, has documented the campaign against them from authorities and pro-government press on a dedicated website, BIRN Under Fire. Television journalist Jet Xharra and BIRN Kosovo took the government to court over the right to report on the prime minister’s accounts, and to set a legal precedent for press freedom in the state. But Xharra, country director of BIRN in Kosovo, said there is a sense of disbelief among those who had to report during war, that these kinds of battles still need to be fought.

“We cannot understand why, 20 years later, you have to deal with [such] a strain on your reporting,” said Xharra.

During the war years that tore Yugoslavia apart, press freedom, like pretty much every other aspect of society, experienced a profound crisis. Large swathes of the media in the former republics became propaganda tools for ruling elites, even before the fighting started. In fact, concerted media campaigns of hate and fear-mongering played an important part in priming people who had lived side by side for decades for war. As British historian Mark Thompson put it in his 1999 book Forging War, on the media’s role in the conflicts in Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia: “War is the continuation of television news by other means.”

|

Dangers of reporting in the Balkins

Attacks on journalists and journalism in the Balkans, compiled from Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project

SERBIA

Independent online news outlet Peščcanik has been targeted on several occasions after reporting in June 2014 that a senior minister had plagiarised parts of his doctoral dissertation. The site has faced distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and hackers have altered text and blocked IP addresses, thus preventing readers from accessing content.

MONTENEGRO

In May 2015, after reporting on corruption in local government, journalist Milovan Novovic’s car was vandalised. In June, journalist Alma Ljuca’s car was attacked in a similar way. This comes after a car belonging to the daily Vijesti was torched in early 2014.

BOSNIA

In December 2014, police raided the Sarajevo offices of news site Klix.ba, looking for a recording in which the prime minister of the country’s Republika Srpska entity spoke about “buying off” politicians. This came after the site’s director and a journalist were interrogated and asked to reveal their source for the recording, which they refused to do.

CROATIA

In May 2015, journalist and blogger Željko Peratović was attacked by three men outside his home, and hospitalised with head injuries. Peratović is known for his investigative reporting, and has covered the trial of two agents of the former Yugoslav Security Agency.

MACEDONIA

Deputy Prime Minister for Economic Affairs Vladimir Peshevski was filmed physically assaulting Sashe Ivanovski, a journalist and owner of the news site Maktel, who has been critical of the government.

SLOVENIA

In March 2015 photojournalist Jani Bozic received a suspended prison sentence for publishing a photo of Alenka Bratusek, then prime minster elect, which showed him receiving a congratulatory text message from a prominent businessman 20 minutes before results were announced.

KOSOVO

Express journalist Visar Duriqi, who has covered radical Islamists in Kosovo, has received a number of death threats, including threats of beheading.

Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project launched as in 2014 to record threats to media freedom throughout the European Union and EU candidate countries. It has recently expanded to cover Russia and Ukraine. |

Yet during the Balkan wars beginning in the 1990s there were local journalists who, in the face of enormous pressure, rejected nationalist and propagandist lines, and attempted to sift truth from lies and distortion. Beyond the daily struggle that came with just existing in a war zone, independent journalism was dangerous work. As Human Rights Watch points out in a new report on the state of media freedom in the Balkans, journalists who were, at the time, “critical of official government positions were often labelled as traitors or spies working on behalf of foreign interests and against the state”.

Serbia’s B92, a rare dissenting voice in a media landscape shaped by President Slobodan Milosevic’s propaganda strategy, is perhaps the most famous example of independent journalism. Set up in 1989 as a youth-focused radio station (later branching out into TV and web platforms), B92 bravely covered a turbulent time – from the war in Bosnia, to the Nato bombing of Serbia, to the protest movement that eventually saw Milošević ousted. For this, it was continuously hounded by the government. At one point in 1999 authorities commandeered its offices and radio frequency, forcing the station off air, before it could resume broadcasting from a different studio and frequency, under the name B2-92.

In Croatia, President Franjo Tudjman also made sure ultra-nationalism had a place in column inches and on airwaves. Feral Tribune, which started out in 1983 as a satirical supplement in the newspaper Slobodna Dalmacija, had other ideas. Under sustained pressure from the authorities, it covered stories of human rights and conflict that many other outlets avoided, in addition to its biting satire. It was taken to court, publicly burned, and one journalist was even drafted into the army after Feral published an edited photo of Tudjman and Milosevic in bed together on the front page.

Bosnia was the country in the region that would be by far the hardest hit by fighting. But even as war came to Sarajevo, independent journalism survived in some small way. Oslobodjenje, which started out as an anti-Nazi paper in 1943, had a track record of editorial independence. In 1988, staff for the first time voted for their own editor – Kemal Kurspahic – instead of accepting one appointed by the authorities. Just three years later they fought for their freedom again, this time in the constitutional court, as the newly elected nationalist parties agreed to adopt a law whereby they could appoint the editors and managers of Bosnian media. In 1992 came their toughest challenge yet. With the two towers of their office building under fire – in one night they lost six floors on one side and four on the other – they decided to go underground, and continue their work from a nuclear bomb shelter, with no newsprint supplies and no phone links.

“If dozens of foreign journalists could come to report on the siege of Sarajevo and Bosnian war, how could we – whose families, city and country were under attack – stop doing our job?” Kurspahic, now managing editor of Connection Newspapers, told Index. They felt an obligation to their readers: “We could not leave them without news at the worst time of their lives.”

Oslobodjenje even celebrated its 50th anniversary during the war, with 82 papers around the world printing some of their stories. With that they achieved “the ultimate victory”, Kurspahic said, “if the aim of the terror against Oslobodjenje was to silence us as a voice of multiethnic Bosnia”.

“People were getting killed, so we were reporting it. The risk was physical at that time to journalists,” Xharra told Index. Today she hosts Kosovo’s most watched current affairs programme, as well as fulfilling her role at BIRN Kosovo. But she cut her reporting teeth as a translator, fixer and field producer for UK broadcasters – the BBC and Channel 4 – during the Kosovo war. She recalled going through frontlines for a story, and hiding tapes from paramilitary checkpoints, painting a vivid picture of a time when practicing journalism in the western Balkans meant near constant risk of physical harm.

Journalists could be caught in crossfire, or targeted specifically for their work. Kurspahic remembers the Oslobodjenje reporter Kjasif Smajlovic in Zvornik, who sent his wife and children away, and stayed to report on the fall of the town until he was killed by Serbian paramilitary forces in April 1992. In 1999, Slavko Curuvija, known for his critical reporting, was shot 17 times in a Belgrade side street, just days after a pro-government daily had labelled him a Nato supporter. In many cases, there has been little to no accountability for such crimes, breeding a culture of impunity that still hangs over the region.

Because while the darkest days for press freedom in the Balkans came during wartime, peace has not brought the improved conditions many hoped for. At a talk in March, Dunja Mijatovic, the OSCE’s free expression representative, went as far as to say that the situation now is worse than in the aftermath of the conflicts.

And today the media itself remains part of the problem, especially when journalists turn on their colleagues. One prominent example is the story of BIRN Serbia. Following their critical investigation into a state-owned power company, Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic labelled the group liars who had been funded by the EU to speak against his government. That attack was then taken forward by the pro-government Serbian press, including in the newspaper Informer. Just one example where the media has been a less than staunch defender of its own rights.

Data from Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project, which tracks media freedom across Europe, indicates that worries of threats to media rights are justified. In just over a year it has received more than 170 reports of violations from the countries of the former Yugoslavia. Incidents included a Croatian journalist who received a letter saying she would “end up like Curuvija”; a Bosnian journalist threatened over Facebook by a local politician; Kosovan journalists depicted as animals on several billboards; a Montenegrin daily that had a company car torched; a Macedonian editor who had a funeral wreath sent to his home; and a Slovenian who faced charges for reporting on the intelligence agency. Online and offline, physical and verbal, serious threats to press freedom remain, some 20 years on.

© Milana Knezevic

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.