18 Jul 2017 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Qatar, Saudi Arabia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Al Jazeera Broadcast Center in Doha, Qatar

A debate at the Frontline Club last night on the future of Al Jazeera and media freedom in the Middle East, following recent calls for the closure of the television network by a group of seven Arab countries led by Saudi Arabia, did not go to plan.

The original chair, BBC security correspondent Frank Gardner, pulled out of the debate and was replaced by Safa Al Ahmad, a Saudi journalist and filmmaker and the winner of the 2015 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Journalism.

According to Arab News, sources within the BBC said Gardner’s decision was because the event was deemed “a propaganda stunt by Qatar and Al Jazeera with no attempt at balance on the panel”. In an email to Arab News, the BBC source allegedly criticised the failure “to invite anyone from the UAE, Saudi, Bahrain or Egypt onto the panel in time”.

A group of 12-15 protesters outside the Frontline Club could be heard during the debate. They chanted, among other things: “Ban Al Jazeera.” They carried Egyptian flags and signs reading: “Al Jazeera Promotes Terrorism.”

This anger was matched inside as audience members aired various grievances, including complaints about the network’s editorial line, its ties to and funding from the state of Qatar, Al Jazeera Arabic’s alleged sectarianism and anti-Shia bias and the treatment of Al Jazeera staff. Some audience members openly supported the calls to ban Al Jazeera.

“Al Jazeera is media prostitution by Qatar,” an audience member shouted at the panel, echoing a protester outside who added that the network wanted to “destroy the Middle East”.

Journalist Ben Flanagan from Arab News, an English-language newspaper published in Saudi Arabia and owned by a member of the House of Saud, put it to the panel that Al Jazeera “has been used as a platform for terrorists and extremists” and asked panelists Giles Trendle, managing director of Al Jazeera English, and Wad Khanfar, the ex-director general of Al Jazeera Media Network: “Do you feel you have blood on your hands?”

During his opening statement, Trendle said: “We are funded by the state of Qatar but we maintain an editorial independence, so there isn’t a lot of direct communication with the channel.”

Khanfar said that while Qatar “is not a charitable organisation”, “the reputation of Al Jazeera and the popularity of Al Jazeera prevented the state of Qatar from using Al Jazeera and they created a healthy distance between us at that time as an editorial newsroom and the state.”

Concerns over the treatment of staff at Al Jazeera almost certainly weren’t eased when Khanfar told Flanagan that if he worked for Khanfar at Al Jazeera he would be fired if he had any objections to interviewing a controversial figure like Osama bin Laden.

“Staff are leaving, but within any organisation there is a certain churn rate,” Trendle later added. “People come and people go.”

At one point an audience member took to the aisle, interrupted Khanfar and shouted something about Al Jazeera’s failure to report on “American involvement” in the 2012 sarin gas attack in Damascus, a conspiracy theory originated by journalist Seymour Hersh and propagated on media outlets such as Alex Jones’ Infowars.

Al Jazeera isn’t the only news outlet Saudi-led coalition’s crosshairs. The London-based Middle East Eye is also on the list. Editor David Hearst, one of last night’s panellists, clarified that the news website is independently funded. “We’re not funded by Qatar,” he said. “If Qatar rolled over, it would have absolutely no effect on us.”

Hearst believes that the reason these Arab states – including Egypt, Bahrain and the UAE – are attacking certain media organisations is that “they are really dead scared of independent criticism or examination of what’s going on,” particularly when such criticism is in Arabic. “They don’t like their own people, Arabs, reading genuinely independent news, and that is what I think started this whole thing off.”

Hearst said that the reach of Al Jazeera, which has an audience 310 million households in more than 100 countries, makes the network, in particular, a threat.

Trendle gave assurances that despite the current pressure, Al Jazeera will not be shutting its doors and remains committed to “balanced, professional” journalism. “It’s kind of business as normal in an abnormal situation,” he said.

“As journalists, we all need to stand together in solidarity against this intimidation, against this bullying. We need to stand against being censored or silenced in any way at all,” Trendle added. “We all need to stand in unison as journalists because journalism is under attack, and in recent years it’s become much clearer that it is coming under attack in a very serious way from governments as well.”

Panellist Marc Owen Jones, a professor at the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies at Exeter University, while agreeing with Trendle, added that there needs to be a broader conversation about public service broadcasting.

“How can we have commercial media if it’s funded by weapons manufacturers? If we’re covering health case, we can’t have it funded by Big Pharma? You have to ask questions. Is it problematic to have media channels funded by non-democratic states or authoritarian states in the region if you want to really progress to another level of journalism?”

A proper debate is still to be had as Monday’s shouting match didn’t quite achieve its aim.

Index on Censorship re-iterates its position given by Index magazine editor Rachael Jolley in June: “Al Jazeera and press freedom must not be used as a bargaining chip.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1500396083270-89581cd9-54bd-6″ taxonomies=”449″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Jun 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Statements, United Arab Emirates

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The call by four Arab states — UAE, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Egypt — for Qatar to close news network Al Jazeera is clearly motivated by a desire to control the media in the region and silence reporting of stories that these governments would rather not see exposed.

Al Jazeera has brought the world news from the Arab Spring and many of the recent important moments from the region. Including the closure of Al Jazeera in a list of demands that Qatar “should” comply with to end a diplomatic crisis is about reducing media freedom in a region where it is already threatened.

“From its treatment of blogger Raif Badawi to its tightly controlled media environment, the Saudi authorities must not be able to dictate access to information for the public in other countries. Al Jazeera and press freedom must not be used as a bargaining chip,” Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship said.

None of the nations involved have a free independent media. Bahrain regularly targets critics, journalists and the one remaining opposition newspaper in the country, Al Wasat. Saudi Arabia sentenced blogger Raif Badawi to 10 years in jail and 1,000 lashes for his “criminal” writings. Egypt has regularly tried journalists on accusations of terrorism. The UAE, too, curtails discussion of its domestic policies. UAE Federal Law No. 15 of 1980 for Printed Matter and Publications regulates all aspects of the media and is considered one of the most restrictive press laws in the Arab world, according to Freedom House. Reporters Without Borders ranks them all below 118, with Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Bahrain all below 160 out of the 180 nations it covers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1498231474147-ef0d779a-68d3-0″ taxonomies=”9044″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Apr 2017 | Awards, Digital Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A schoolboy resident of Bahrain and a recent PhD student in computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, Bill Marczak co-founded Bahrain Watch in 2012. Seeking to promote effective, accountable and transparent governance, Bahrain Watch works by launching investigations and running campaigns in direct response to social media posts coming from activists on the front line. In this context, Marczak’s personal research has proved highly effective, often identifying new surveillance technologies and targeting new types of information controls that governments are employing to exert control online, both in Bahrain and across the region. In 2016 Marczak investigated several government attempts to track dissidents and journalists, notably identifying a previously unknown weakness in iPhones that had global ramifications.

Index spoke with Marczak in the run up to the Freedom of Expression Awards, where he is nominated for the Digital Activism award.

Ryan McChrystal: In the summer of 2016 you discovered a previously known weakness in Apple’s iPhone that had global ramifications. Can you talk us through how that first came to light?

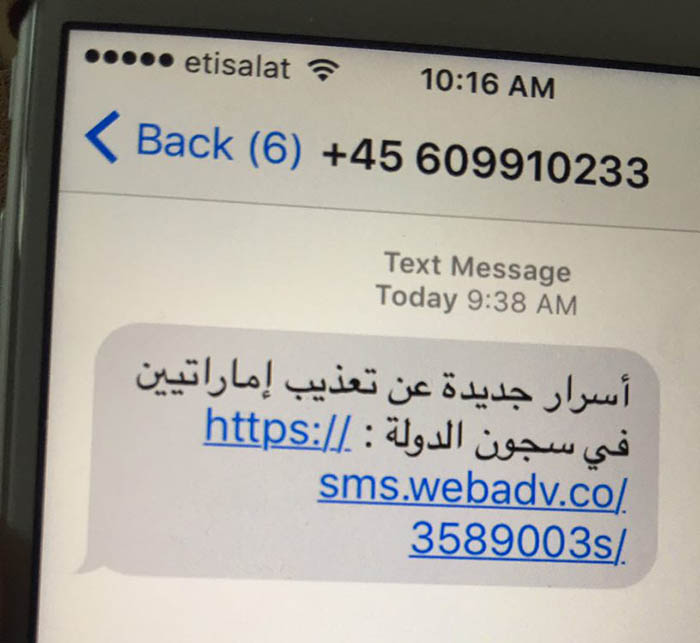

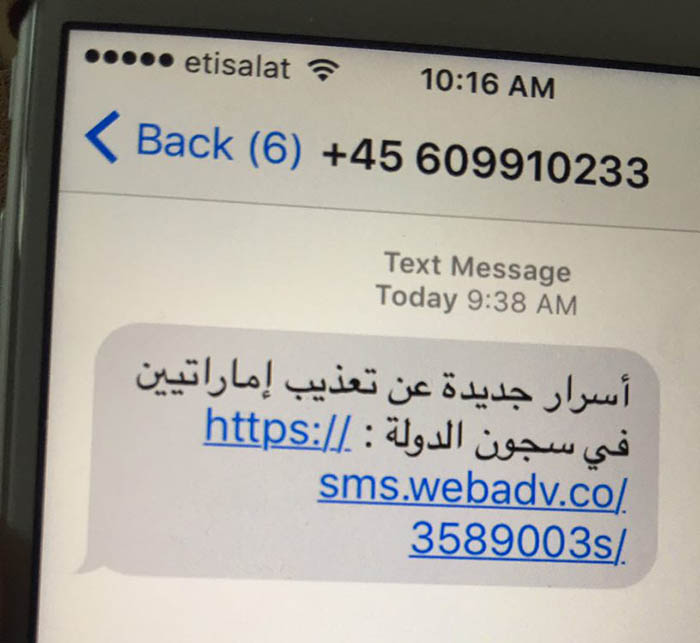

Bill Marczak: In August of 2016, Ahmed Mansoor, an activist in the UAE, reached out to me after he had received suspicious text messages. I had known him previously because he gets suspicious things in his inbox or on phone quite frequently. He sent me these text messages and asked me to take a look. The messages said: “New secrets about detainees tortured in UAE prison.” And there was a link inside the text message which I recognised because it was connected to a series of websites I had been tracking for the past six months or so. I had already attributed them to the NSO Group (an Israeli spyware company).

At that point, I was able to get the spyware they were using to target Mansoor

McChrystal: What does the software actually allow governments to do? What are the dangers for activists?

Marczak: The malware that NSO sells, called Pegasus, is actually pretty sophisticated in what it can collect. In the security community, the iPhone is generally thought to be more secure because Apple goes to such lengths to lock down and make it really, really hard to install an application from outside the App Store and to do something to the device that’s not approved by Apple. The fact that this malware even existed and could affect an iPhone in the single touch of a button was very surprising. Once your phone is infected, the malware would essentially be able to see everything on the device. If you had any saved passwords, for example, they would all be sent back to whoever infected you. That person would also get the ability to intercept your calls, SMS, Whatsapp, Viber, or any other communication service you use.

Perhaps most scarily, the malware allowed the user to turn on the webcam and the microphone on your iPhone to spy on activity going on around the phone. This could be used to spy on meetings or to see who you were hanging around with.

McChrystal: And this was was the first piece of malware of its kind.

Marczak: That’s correct. It was the first known zero-day remote jailbreak for the iPhone that was used as part of spyware. A jailbreak is a piece of software that allows you to get around Apple’s security precautions for the phone. Jailbreaking started out as a way for hobbyists and enthusiasts to install their own software not approved by Apple on the iPhone, so it was a very innocuous line of research. But once iPhones became more popular, people started putting their whole lives on their phones. That’s when jailbreaks became really, really valuable to people who would want to spy on iPhone users.

Nowadays, there are companies that will pay you if you sell them software or the code that jailbreak the phone. Some companies, like Zerodium, offer up to $1.5m. Presumably they’ll then be able to sell it to interested users for even more.

McChrystal: How did Apple respond when you informed them of your discovery?

Marczak: Working with the folks at Citizen Lab, I got in touch with Apple very early on in the process to alert them of what we had found. Initially, when we called up Apple was like: “Yeah, yeah, sure, send us some details and we’ll take a look.” When we sent what we were able to pull down from those links, the tone changed right away and they realised this was really serious. They said: “Give us more information because we want to work closely with you on this.”

McChrystal: How are governments using this kind of malware maliciously? And why should human rights activists specifically be worried?

Marczak: This kind of software can be used, for instance, in legitimate criminal investigations, but it can also be used essentially for anything the government wants to use it for. Once NSO Group sells the spyware to a government, that’s where NSO’s ability to control things ends. The government can then decide who it wants to target, who it wants to infect. If sold to a government agency that has a history of abusing surveillance, it’s likely they are going to abuse it to target human rights defenders and political opponents.

It’s something that human rights activists should be concerned about because everything is moving online these days. They are on their phones, communicating with other activists, human rights violations are being documented by videos or pictures on the phone. Your confidential or secret sources might be a WhatsApp contact, or a Signal contact if you’re even more secure.

If just one person has been infected, governments can map out an entire network of human rights defenders or opponents. They can keep tabs on an entire operation or human rights infrastructure in a country.

McChrystal: By bringing this malware to light, how many people’s privacy do you think you’ve helped to protect? Is there a way to put a number on it?

Marczak: The patch that Apple released, which coincided with the report that I published with Citizen Lab, went out to every iPhone user around the world. Apple subsequently issued a patch to every Mac laptop and desktop user. The number is in the high hundred of millions, if not billions of people whose phones and computers were patched.

Of course, not all of those people would have been affected, but having that sort of broad impact was very exciting.

McChrystal: Are you yourself now in danger of cyber attacks? Have there been any attempts that you’ve noticed?

Marczak: It’s something that I’ve thought a lot about. If you look at the security industry as a whole, researchers themselves can be very easily targeted. There have been instances where foreign intelligence agencies have targeted anti-virus companies, for instance, to figure out what they are working on next.

That’s the main risk I am worried about: if some foreign intelligence agency decides “hey, Bill’s working on some interesting stuff. Let’s hack him and see what he’s up to.”

When I’ve done some work in the field, for instance in the Middle East, I think through a set of operations security procedures like how to prevent someone coming into my hotel room when I’m away and bug my laptop.

McChrystal: What’s your connection to Bahrain and how did that lead to the establishment of Bahrain Watch?

Marczak: My own connection with Bahrain began in 2002. I went to high school there because of my dad’s job. Going to high school in a place, you obviously develop a lot of connections and experiences that tie you there, at least emotionally. Bahrain very much feels like one of my homes.

While I was there, I was never much interested in the political situation. But going back to the USA for college and observing from abroad, I did start to notice by reading the international media that there were certain things not right with the country, especially in 2011, when the Arab Spring protests started. Once I saw that police were shooting protesters in the street, and that one of my homes was in crisis, I though if there was a way that I, a computer science student sitting in Berkeley, California, could do anything to have a positive impact on the situation.

At the time, I didn’t really know what to do. I started following Bahraini activists, people on the ground and those who were actually at the protests. Those involved in the Arab Spring very much engaged with the rest of the world through social media. They sometimes sent out pictures of shotgun shells or tear gas canisters, asking if anyone knew who was manufacturing and supplying the government with them.

I was able to respond to these requests and see if I could find out some new information. I started off doing research into the various kinds of weapons that the police were using. That initial research got me some recognition among activists on the ground. We got in touch and developed connections which led us to decide to found Bahrain Watch in 2012.

Bahrain Watch initially focused on these arms, but them later expanded to documenting western PR companies that the government had hired to influence the media narrative. It expanded from there to a bunch of different areas.

McChrystal: The situation for human rights activists in Bahrain is changing, and in many ways it’s become more difficult. What does this mean for Bahrain Watch operations over the next year?

Marczak: You’re definitely right that the situation on the ground is very bad. In the past year we’ve seen the continued harassment of human rights defenders on the ground. One of the things we are trying to do going forward is to is, we started off in 2012 as an all-volunteer organisation and we were very much sustained by the energies and the passions of the Arab Spring.

But in the years since, a lot of that energy has died off to an extent, not just in Bahrain, but in the broader activist community. One of our challenges going forward has been to try and formalise the organisation so that we’re actually getting funding and have the capacity and resources to undertake more longer-form types of work. We’ve got some of that already, we have gotten a bit of funding, and we’re looking mainly to continue our work with digital security, so trying to provide support and advice to dissidents on the ground to help enhance their security posture, given the ongoing crackdown by the government.

At the same time we want to do more broader types of investigations into corruption more closely into the government’s strategy of controlling the media.

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2017 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1490258649778{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/donate-heads-slider.jpg?id=75349) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1491488367891-c15491ac-4f30-3″ taxonomies=”8734″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Feb 2017

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Youth Advisory Board” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center|color:%230a0a0a” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Youth Advisory Board” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center|color:%230a0a0a” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

The youth advisory board is Index on Censorship’s project aimed at engaging with young people aged 16-25 from around the world and gathering their views on freedom of expression issues.

What is the youth advisory board?

The youth board is a specially selected group of young people aged 16-25 who advise and inform Index on Censorship’s work, support our ambition to fight for free expression around the world and ensure our engagement with issues with tomorrow’s leaders. The current members are sitting from January to June 2020.

Why does Index have a youth board?

Index on Censorship is committed to fighting censorship not only now, but also in future generations, and we want to ensure that the realities and challenges experienced by young people in today’s world are properly reflected in our work.

Index is also aware that there are many who would like to commit some or all of their professional lives to fight for human rights and the youth board is our way of supporting the broadest range of young people to develop their voice, find paths to freely expressing it and potential future employment in the human rights, media, and arts sectors.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column][vc_column_text css_animation=”none”]

Applications now open!

We are looking for enthusiastic young people, aged between 16-25, who must be committed to taking part in monthly meetings, which are held online with fellow participants. Applicants can be based anywhere in the world. We are looking for people who are communicative and who will be in regular touch with Index.

Each youth advisory board sits for six months, has the chance to participate in monthly video conferencing discussions about current freedom of expression issues from around the world, which sometimes include guest speakers. There are exciting opportunities to be interviewed for the podcast and contribute to Index’s Instagram page.

The next youth board is currently being recruited, and will sit from July to December 2020.

How to apply

Please send us the following:

- Cover letter

- CV

- A 250-word blog post about any free speech issue

Applications can be submitted to Orna Herr at [email protected]. The deadline for applications is 26 July at 11:59pm GMT.

What is the youth advisory board?

The youth board is a specially selected group of young people aged 16-25 who advise and inform Index on Censorship’s work, support our ambition to fight for free expression around the world and ensure our engagement with issues with tomorrow’s leaders. The current members are sitting from July to December 2019.

Why does Index have a youth board?

Index on Censorship is committed to fighting censorship not only now, but also in future generations, and we want to ensure that the realities and challenges experienced by young people in today’s world are properly reflected in our work.

Index is also aware that there are many who would like to commit some or all of their professional lives to fight for human rights and the youth board is our way of supporting the broadest range of young people to develop their voice, find paths to freely expressing it and potential future employment in the human rights, media, and arts sectors.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner disable_element=”yes”][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Shini Wang” title=”USA” profile_image=”108370″]Shini Wang is a poet, journalist, and BA student of philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin. She is a member of her university’s liberal arts council, the editor of The Liberator Magazine, and a host of open discussions on campus. Interested in how freedom of expression plays into the creative and imaginative process of international writers and artists who witness injustice, her research investigates censorship and its effects during our post-truth political era.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Nikhil Singh” title=”India” profile_image=”108371″]Nikhil Singh is a law student based in Kolkata, India. He has a keen interest in advocating the right to free speech and often spends his free time promoting it. In the past he has interned with senior advocates in the Supreme Court of India, and has worked on cases involving violation of the right to free speech, civil liberty, and human rights. After graduating from college, Singh intends to work in the legal industry, to fight for people’s rights.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Charles Terroille” title=”France” profile_image=”108373″]Charles Terroille is a French dual degree student in political science and international relations at Sciences Po (Lille) and the University of Kent. His field of work covers media and journalism. After directing his first TV documentary about Dharavi in India at 16 years old, he continued to report in different types of newsrooms in France and the UK. Terroille also specialises in the issue of whistleblowers and has worked on the Luxleaks and Football Leaks cases. He collaborated with the Signals Network Foundation for advocacy and research on the leaks. Terroille is also the founder and director of the International Consortium of Student Journalism (ICSJ).[/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Emma Quaedvlieg” title=”Serbia” profile_image=”104865″]Emma Quaedvlieg is a Master’s graduate from the Institute of Development Studies, where she focused on popular movements and inequality. She also holds a BA (Hons) in politics and international relations from the University of Nottingham. She has actively campaigned for various gender issues and was elected women’s officer for the student’s union in Nottingham. Her research largely focuses on the western Balkans, where she is contributing to freedom of expression and wider development in local government. Quaedvlieg has also worked in various (international) human rights organisations.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner disable_element=”yes”][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Arpitha Desai” title=”India” profile_image=”104862″]Arpitha Desai is a lawyer based in New Delhi, India. As an avid student of constitutional law, she is passionate about civil liberties with a keen interest in censorship, surveillance, and digital rights. Keeping in mind the ever-evolving nature of technology and the needs of the government, industry, and common man, Desai believes that law and policy must strike a holistic balance between conflicting rights.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Krzysztof Katkowski” title=”Poland” profile_image=”108374″]Krzysztof Katkowski is a student of Czacki High School in Warsaw. He is a young activist and journalist cooperating with “Krytyka Polityczna” where he focuses on youth’s community-minded engagement and education. Passionate about science, literature, and philosophy, he wants to popularise the idea of free speech and dialogue between different environments. In the future, Katkowski wants to fight for open society and tolerance which is endangered in recent years, especially in Poland.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Elyse Popplewell” title=”Australia” profile_image=”108372″]Elyse Popplewell is the social media editor at The Australian, the most widely circulated national newspaper in Australia. After attaining a bachelor of communications (journalism) at the University of Technology, Sydney, she began her career at the Institute for Economics & Peace, the think tank that publishes the Global Peace Index annually. Popplewell focuses on the issue of Australian defamation laws gagging important journalism and movements like #MeToo.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Recent posts” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”6514″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Meet the Board

The current board is sitting from July to December 2020.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Aliyah Kaitlyn Orr” profile_image=”112187″]Aliyah Kaitlyn Orr (pen name A.K. Nephtali) is a college student in Britain. Orr has been inspired by the power of words ever since a novel helped them realise their gender-neutral identity. Orr writes inclusive fiction that aims to empower LGBTQ+ people around the world. One of their short stories will be published in a digital anthology by the end of 2020. [/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Subhan Hasanli” profile_image=”114478″]Subhan Hasanli is a 25 year old lawyer, who works with local and international human rights organisations in Azerbaijan. He holds a bachelor’s degree in law from Nakhichevan State University. His goal is to promote the rule of law and human rights, and he hopes to achieve changes in these fields. Hasanli’s hobbies include catching fish, playing chess and reading books about science, politics, and philosophy. His favourite book is Diplomacy by Henry Kissinger. [/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Carmen Ferri” profile_image=”114479″]Carmen Ferri is a digital rights activist based in Canada. She obtained an undergraduate degree in cultural studies and sociology at Maastricht University, Netherlands, and a master’s degree from the University of Amsterdam in new media and digital culture. During her studies, she worked on projects related to disinformation, hate speech and subcultural expression on digital platforms. Ferri has completed two internships with the Association for Progressive Communications. She worked as a policy analyst intern researching counter-hate speech movements in Asia, then as a communications research intern where she implemented a project examining actors and discourses within digital rights spaces on social media.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][staff name=”Sneha” profile_image=”114480″]Sneha graduated from the Asian College of Journalism with a postgraduate diploma in journalism (new media) and is now a journalist for The Times of India. She previously worked as a reporter for the International Business Times. Sneha is concerned about the issues around press freedom in her country. She is an advocate for open discourse in the hope that it will lead to solutions. Sneha has an avid interest in governance, ecology, environment and urban planning.[/staff][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][staff name=”Pablo Aguera” profile_image=”114481″]Pablo Aguera is a research fellow for Research ICT Africa working on digital rights, data justice and internet access and use. Aguera has produced creative multimedia projects and worked with social enterprises and youth movements across multiple countries. He holds a BSc in philosophy, politics and economics from the University of Warwick, and is currently completing a dual master’s degree in global media and communications at the London School of Economics and the University of Cape Town.

[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][staff name=”Siphesihle Fali” profile_image=”114482″]Siphesihle Fali is in her final year studying English literature & language, and media and writing at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. Fali is passionate about expanding her knowledge on societal constructs and the definitions of freedom. She aspires to create real conversations around the right to freedom of expression for the most censored and vulnerable communities, to safeguard and protect their rights. Fali’s interests lie mostly with the rights of women and children, and she intends on dedicating her career to being a voice for those who are denied one.[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][staff name=”Claes Kirkeby Theilgaard” profile_image=”114483″]Claes Kirkeby Theilgaard works as the editor-in-chief of the Danish online newspaper 180Grader. He is set to begin his studies in business and communications at the Copenhagen Business School. Theilgaard has worked in journalism and in various political organisations with the aim of furthering democracy and freedom, which has resulted in violent threats and other forms of intimidation. These experiences have made him more motivated to fight for the cause of free speech. Theilgaard is currently working to launch a campaign against “hate speech” laws in Denmark, as well as an organisation to fight censorship and work for free speech both in Denmark and abroad.[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][staff name=”Cecily Donovan” profile_image=”114484″]Cecily Donovan graduated from Boston University with degrees in International Relations and Political Science in 2019. She currently lives in New York City working in economic development for Invest Northern Ireland, a UK government agency. She has a background in state government, French language and politics, and European affairs. Donovan is passionate about women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, the Black Lives Matter movement and the impact of authoritarianism on freedom of expression globally.

[/staff][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Youth Advisory Board” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center|color:%230a0a0a” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Youth Advisory Board” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:center|color:%230a0a0a” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]