22 Jun 2016 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

From left, Ahmet Nesin (journalist and author), Şebnem Korur Fincancı (President of Turkey Human Rights Foundation) and Erol Önderoğlu (journalist at Bianet and RSF Turkey correspondent). (Photo: © Bianet)

I have known Erol Önderoğlu for ages. This gentle soul has been monitoring the ever-volatile state of Turkish journalism more regularly than anybody else. His memory, as the national representative of the Reporters Without Borders, has been a prime source of reference for what we ought to know about the state of media freedom and independence.

On 20 June, perhaps not so surprisingly, we all witnessed Erol being sent to pre-trial detention, taken out of the courtroom in Istanbul in handcuffs.

Charge? “Terrorist propaganda.” Why? Erol was subjected to a legal investigation together with two prominent intellectuals, author Ahmet Nesin, and Prof Şebnem Korur Fincanci – who is the chairwoman of the Turkish Human Rights Foundation – because they had joined a so-called solidarity vigil, as an “editor for a day”, at the pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem daily, which has has been under immense pressure lately.

This vigil had assembled, since 3 May, more than 40 intellectuals, 37 of whom have now been probed for the same charges. One can now only imagine the magnitude of a crackdown underway if the courts copy-paste detention decisions to all of them, which is not that unlikely.

Journalism has, without the slightest doubt, become the most risky and endangered profession in Turkey. Journalism is essential to any democracy. It’s demise will mean the end of democracy.

Turkey is now a country — paradoxically a negotiating partner with the EU on membership — where journalism is criminalised, where its exercise equates to taking a walk on a legal, political and social minefield.

“May God bless the hands of all those who beat these so-called journalists” tweeted Sait Turgut, a top local figure of AKP in Midyat, where a bomb attack on 8 June by the PKK had claimed 5 lives and left more than 50 people wounded.

Three journalists – Hatice Kamer, Mahmut Bozarslan and Sertaç Kayar – had come to town to cover the event. Soon they had found themselves surrounded by a mob and barely survived a lynch attempt.

Most recently, Can Erzincan TV, a liberal-independent channel with tiny financial resources but a strong critical content, was told by the board of TurkSat that it will be dropped from the service due to “terrorist propaganda”. Why? Because some of the commentators, who are allowed to express their opinions, are perceived as affiliated with the Gülen Movement, which has been declared a terrorist organisation by president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

It is commonplace for AKP officials from top down demonise journalists this way. Harrassment, censorship, criminal charges and arrests are now routine.

Detention of the three top human rights figures, the event in Midyat or the case of Can Erzincan TV are only snapshots of an ongoing oppression mainly aimed at exterminating the fourth estate as we know it. According to Mapping Media Freedom, there have been over 60 verified violations of press freedom since 1 January 2016.

The lethal cycle to our profession approaches its completion.

While journalists in Turkey – be they Turkish, Kurdish or foreign – feel less and less secure, the absence of truthful, accurate, critical reporting has become a norm. Covering stories such as the ”Panama Papers” leak — which includes hundreds of Turkish business people, many of whom have ties with the AKP government — or the emerging corruption case of Reza Zarrab — an Iranian businessman who was closely connected with the top echelons of the AKP — seems unthinkable due to dense self-censorship.

Demonisation of the Kurdish Political Movement and the restrictions in the south eastern region has made it an extreme challenge to report objectively on the tragic events unfolding in the mainly Kurdish provinces which have forced, according to Amnesty International, around 500,000 to leave their homes.

Journalism in Turkey now means being compromised in the newsrooms, facing jail sentences for reportage or commentary, living under constant threat of being fired, operating under threats and harassment. A noble profession has turned into a curse.

In the case of Turkey, fewer and fewer people are left with any doubt about the concentration of power. It’s in the hands of a single person who claims supremacy before all state institutions. The state of its media is now one without any editorial independence and diversity of thought.

President Erdoğan, copying like-minded leaders such as Fujimori, Chavez, Maduro, Aliyev and, especially, Putin, did actually much better than those.

His dismay with critical journalism surfaced fully from 2010 on, when he was left unchecked at the top of his party, alienating other founding fathers like Abdullah Gül, Ali Babacan and others who did not have an issue with a diverse press.

Soon it turned into contempt, hatred, grudge and revenge.

He obviously thought that a series of election victories gave him legitimacy to launch a full-scale power grab that necessitated capturing control of the large-scale media outlets.

His multi-layered media strategy began with Gezi Park protests in 2013 and fully exposed his autocratic intentions.

While his loyal media groups helped polarise the society, Erdoğan stiffly micro-managed the media moguls with a non-AKP background — whose existence depended on lucrative public contracts — to exert constant self-censorship in their news outlets, which due to their greed they willingly did.

This pattern proved to be successful. Newsrooms abandoned all critical content. What’s more, sackings and removals of dignified journalists peaked en masse, amounting now to approximately 4,000.

By the end of 2014, Erdoğan had conquered the bulk of the critical media.

Since 2015 there has been more drama. The attacks against the remaining part of the critical media escalated in three ways: intimidation, seizure and pressure of pro-Kurdish outlets.

Doğan group, the largest in the sector, was intimidated by pro-AKP vandalism last summer and brought to its knees by legal processes on alleged “organized crime” charges involving its boss.

As a result the journalism sector has had its teeth pulled out.

Meanwhile, police raided and seized the critical and influential Koza-Ipek and Zaman media groups, within the last 8 months, terminating some of its outlets, turning some others pro-government overnight and, after appointing trustees, firing more than 1,500 journalists.

Kurdish media, at the same time, became a prime target as the conflict grew and more and more Kurdish journalists found themselves in jail.

With up to 90% of a genetically modified media directly or indirectly under the control Erdoğan and in service of his drive for more power, decent journalism is left to a couple of minor TV channels and a handful newspapers with extremely low circulations.

With 32 journalists in prison and its fall in international press freedom indexes continuing to new all-time lows, Turkey’s public has been stripped of its right to know and cut off from its right to debate.

Journalism gagged means not only an end to the country’s democratic transition, but also all bridges of communication with its allies collapsing into darkness.

A version of this article originally appeared in Süddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

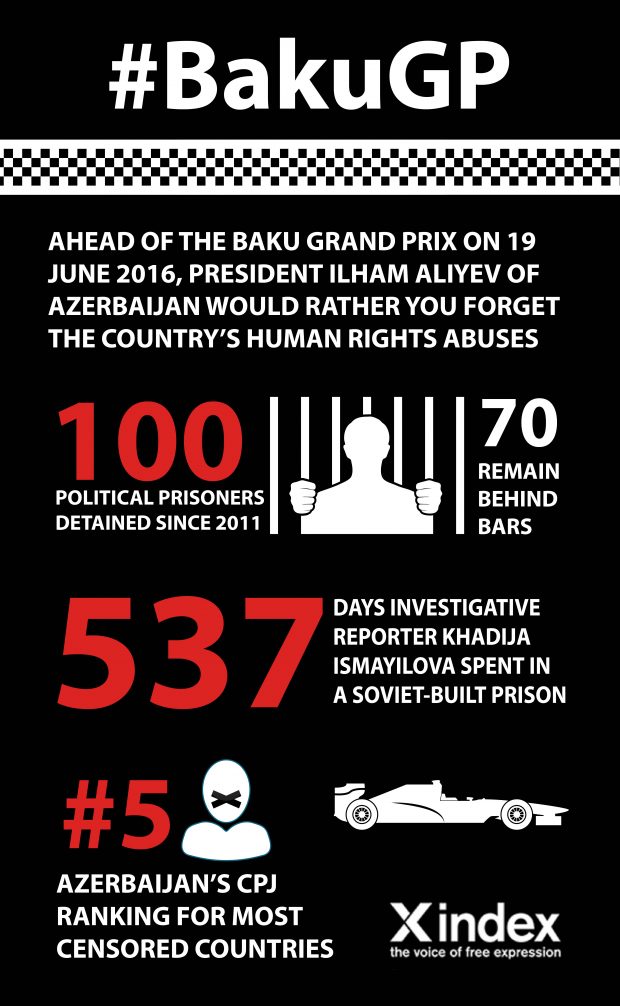

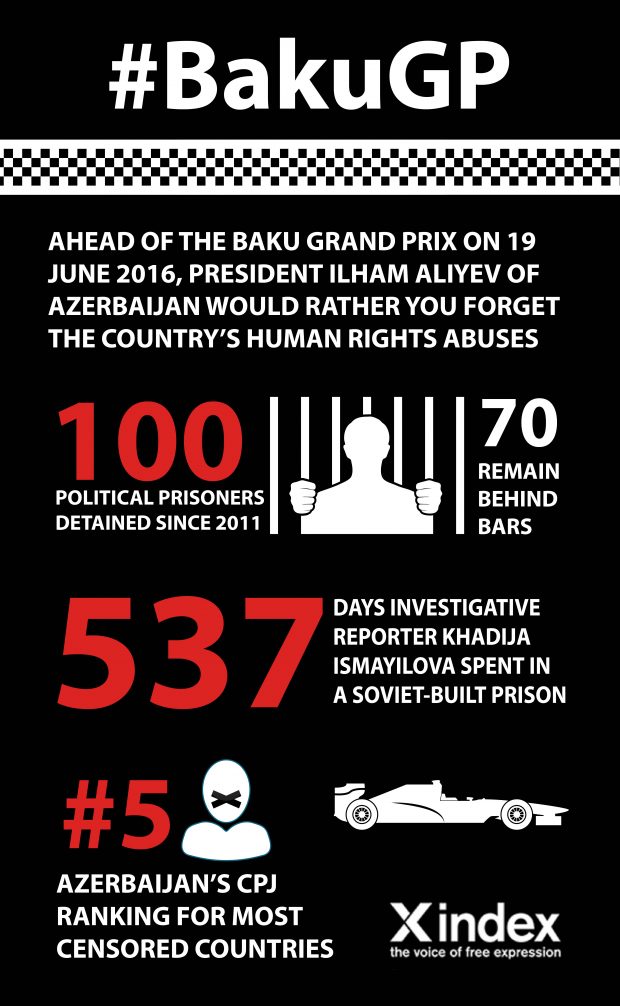

16 Jun 2016 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News and features

“Having seen the development work in Baku as it’s neared completion over the past few months, it’s clear that the organisers have put a lot of planning and resources into the infrastructure around the circuit, and it promises to be a very significant event in the region.” So said Fernando Alonso, Formula One double World Champion and “Baku Ambassador” ahead of the European Grand Prix on the streets of the city on 19 June.

In his ambassador role, Alonso observed the progress being made on the streets of the Azerbaijani capital during an 8-9 March visit. What he almost certainly didn’t observe was the dire human rights situation in the country that has seen an assault on fundamental freedoms and attempts to silence critical voices.

The reason he wouldn’t have seen such abuses is because the Azerbaijani government has gone to great lengths to make the country appear as law-abiding and democratic in an attempt look legitimate and draw foreign money.

Azerbaijan has previously hosted other significant sports and cultural events — including the inaugural European Olympic Games in 2015 and the Eurovision Song Contest in 2012 — but as son of the country’s sports minister, Aria Rahimov, said, the upcoming Grand Prix is an opportunity “to promote our city from different points: from the touristic point of view, investment”.

There are many things President Ilham Aliyev’s autocratic regime, which has been in power since 2003, would rather we didn’t promote. Here are just three.

His government has:

1) Imprisoned journalists, activists and opposition politicians.

Over 100 political prisoners have been detained since 2011, when during the Arab Spring the country’s rulers feared an uprising at home. Around 70 of these prisoners remain behind bars.

Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova may have been released from prison last month, but two trumped-up charges against her — illegal entrepreneurship and tax evasion –remain. Her seven-and-a-half-year jail sentence has only been reduced to a three-and-a-half-year suspended term and she isn’t free to leave the country.

Many others, including journalist Seymur Hezi, are still serving prison sentences on charges that were widely condemned for being politically motivated to silence outspoken critics of the government of President Aliyev.

2) Led a crackdown on independent media outlets.

The Committee to Protect journalists lists Azerbaijan as the fifth most censored country in the world, ahead of Iran, China and Cuba. The ranking is in part due to the lack of independent media as “offices have been raided, advertisers threatened, and retaliatory charges such as drug possession levied against journalists”.

Azerbaijan’s independent media is under attack more than ever before. Most recently, editors of the Index award-winning opposition newspaper Azadliq received a letter from the Azerbaijan publishing house with a warning of discontinuation of the newspaper if it does not pay off its debts before 27 June. Azadliq — widely recognised as one of the last remaining independent news outlets operating inside the country — is convinced that the authorities are deliberately trying to put it out if business.

3) Allowed a climate of violence against critics to fester.

Torture and ill-treatment are widespread against political prisoners. Youth activists Bayram Mammadov and Giyas Ibrahimov were tortured in May 2016, allegedly to draw confessions for trumped-up drugs charges.

Public attacks against journalists are widespread and murder is not uncommon. In 2005, Elmar Huseynov, an independent Azerbaijani journalist, widely known for his harsh criticism of Azerbaijani authorities and president Aliyev, was murdered in outside his home in Baku. In 2011, Rafiq Tağı, who had written an article deemed to be critical of Islam and the Islamic prophet Mohammed was stabbed in a car park near his home, later dying in Baku hospital.

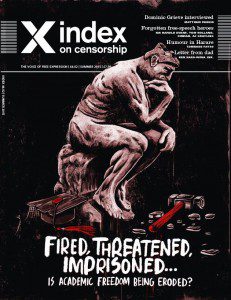

28 Apr 2016 | Academic Freedom, Academic Freedom Reports, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Academic freedom has been the subject of many debates in recent months. With speakers regularly being no-platformed, and increasing violations of safe space, universities and student unions across the UK have faced harsh criticism.

This growing trend of banning speakers from debates rather than confronting their views head on has led to calls for reforms in university policies in protecting academic freedom and so-called “safe space”.

When human rights activist and ex-Muslim Maryam Namazie was invited by the Atheist, Secularist and Humanist Society (ASH) to speak at Goldsmiths University in December 2015 she faced heckles and interruptions from students who opposed her views.

Throughout Namazie’s talk about blasphemy and apostasy members of Goldsmiths University’s Islamic Society (ISOC) caused a disruption by laughing, shouting out and even switching off her presentation, leading to some students being removed by security.

Namazie spoke to Index about the importance of academic freedom, stating: “Universities have always been hotbeds of dissent and progressive politics. They are places where anything can and should be discussed and debated – where deeply held sensibilities and beliefs can be reviewed, opposed and challenged.

“If you can’t express yourself on a university campus, doing so off-campus is usually even harder. Where academic freedom is restricted, it is a measure of the limits of free speech in society at large.”

Speaking about the Goldsmiths incident, Namazie refuses to be intimidated. She believes those pushing the Islamist narrative want to prevent a counter-narrative on university campuses and therefore it is more important for her to go and speak on any campus she is invited to and to push to be allowed where she is denied access.

“My family fled the Islamic regime of Iran in order to live freer lives. Therefore, it’s especially important for me to speak up, particularly given how many face imprisonment or lose their lives in doing so. I feel I have an added responsibility to speak for those who cannot,” she told Index.

In September 2015 Namazie was invited to speak at Warwick University by the Warwick Atheists, Secularists and Humanists’ Society, but her invitation was withdrawn by the University’s Student Union, who claimed her views would “incite hatred on campus”.

Other activists including Germaine Greer and Julie Bindel have also been silenced on campuses for their controversial views.

Namazie believes no-platforming is having a chilling effect on students’ academic freedom. She told Index: “These policies equate speech with real harm and violence though clearly there is a huge distinction between speech and action. Criticising Islam and Islamism, for example, is not the same as attacking Muslims. Nonetheless, I have been accused of ‘inciting violence’ or ‘inciting discrimination’ against Muslims.”

Human rights activist Peter Tatchell was involved in a dispute in February after National Union of Students’ LGBT representative Fran Cowling, declined to attend an event at the Canterbury Christ Church University at which Tatchell was giving a keynote address and participating on a panel.

He told Index: “Academic freedom is a crucial element of a free and open society. The right to explore, research, articulate, debate and contest ideas — even disagreeable ones — is a democratic hallmark.

“Imposing restrictions is the slippery slope to authoritarianism. As well as diminishing the realm of knowledge and understanding, it reinforces conformism and the status quo; putting a break on dissent and innovation.”

Right2Debate are a student-led movement who are campaigning for an end to censoring and no-platforming in universities by calling for student unions to reform their policies contesting rather than removing divisive and extremist narratives.

The movement, which has 100 student activists across 12 different UK universities and a further 3000 signatures of support, are aiming to have their four-point policy implemented by student unions across the UK. The policy’s outcomes include debate taking place over censorship, uncontested platforms for extremist speakers and transparency in the way the student unions conduct external speaker policy and challenging extremist/divisive narratives.

Haydar Zaki, Quilliam’s Outreach Right2Debate programme coordinator, told Index: “We are in this hostile environment to free speech because of the fruitless terms that have been employed at universities which include safe spaces and duty of care. In reality, these terms are completely open to interpretation, and have led to the chaos we see today whereby speakers are banned (or initially banned) at one university, but then freely allowed in others.

“What student unions and universities need to do is actually start implementing policies that are transparent and uniform — emphasising academic rights and the right to challenge over censorship.”

Bigoted ideas in society need challenging. To do so students require an academic environment that is willing to have open and civil discussions on all types of ideas, including those that could be deemed offensive, believes Benjamin David, an editor at Right2Debate.

Academic freedom is also essential for developing as a society, he told Index: “Academic freedom is important for a variety of reasons, none so pressing than the instrumental value that it has in making advancements in science, law or politics. Such advancements necessitate that the free discussion of opinion is available.”

The summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine which focuses on academic freedom. Subscribe here to get your copy.

Professor Chris Frost, former head of journalism at Liverpool John Moores University, agrees. Frost believes academic freedom is important for new ideas to be explored. He told Index: “Academic freedom is critical as it allows academics to investigate matters that may be generally considered socially unacceptable simply because there has been no previous investigation. We cannot expand knowledge and understanding if we don’t challenge socially accepted concepts and seek proof to support our theories. Preventing academic research leads to a stifled society and one that will eventually destroy itself through its own limitations.”

Academic freedom is a regular topic for debate for the Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board, a group of young professionals who meet up for monthly online meetings to discuss current free speech issues. The board spoke to Index about why academic freedom is important to them.

Board member, freelance journalist and race, ethnicity and conflict Masters student, Layli Foroudi, told Index: “Academic freedom is important to me because the purpose of research and study should be to investigate reality, to seek to shed light on some aspect of life, or “truth” — and most importantly, to challenge other people’s truth claims. If there is no academic freedom then there will only be a narrow view of reality that is being purported and left unchallenged.”

Mark Crawford, a postgraduate student specialising in Russian and post-Soviet politics at University College London and current board member, added: “As a historian, it always seemed to me that academic freedom was the closest anyone can really get to ideas breaking down monopolies of power -– hard, scientific investigation can cut through the emotions around nationalism or religion, and afterwards you’re left with truths that however inconvenient are always extremely necessary for new and better narratives to be built.”

This article was updated on 3 May 2016. Corrects to clarify the nature of the dispute over Peter Tatchell’s appearance at Canterbury Christ Church University.

Josie Timms is editorial assistant at Index on Censorship and the first Liverpool John Moores University/Tim Hetherington fellow.

Related:

Why is freedom of speech important?

Worst countries for restrictions on religious freedom

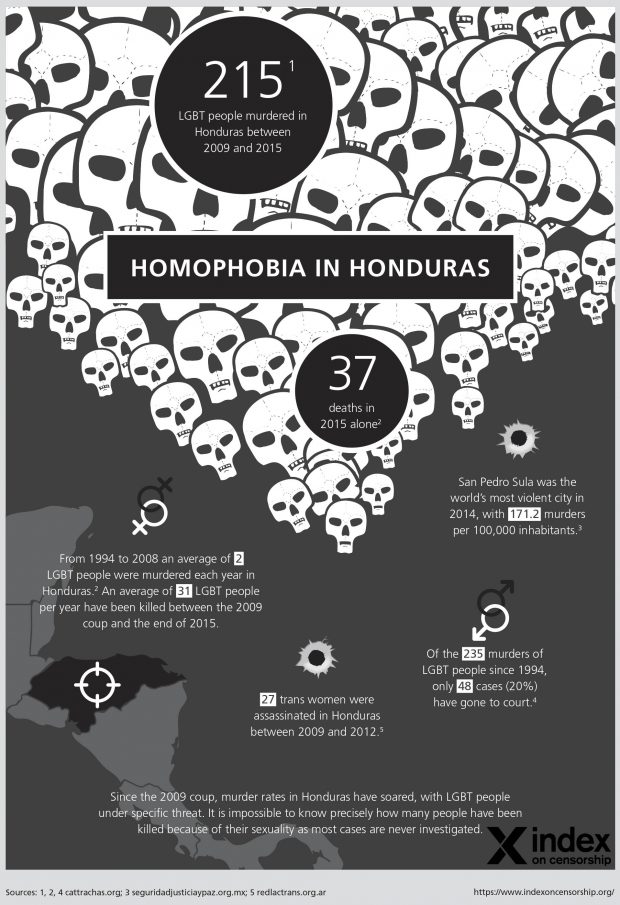

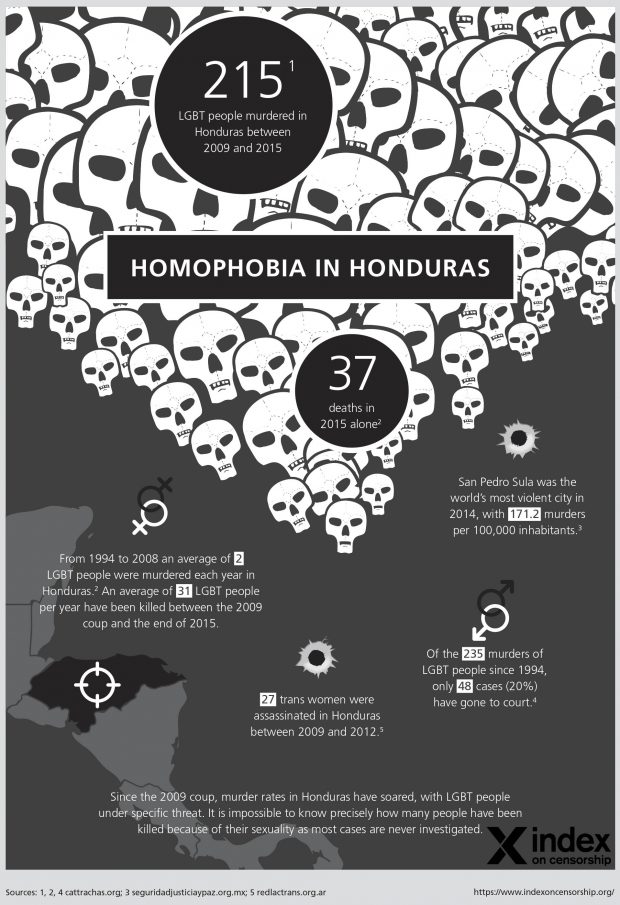

20 Apr 2016 | Americas, Honduras, Magazine, mobile, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016

[This article is also available in Spanish]

A year after returning from exile, Honduran gay rights activist Donny Reyes still fears a murderous attack at any minute.

“I’ve been imprisoned on many occasions. I’ve suffered torture and sexual violence because of my activism, and I’ve survived many assassination attempts,” he said, in an interview with Index on Censorship.

Activists in Honduras must contend with a constant barrage of threats and, often fatal, attacks. Reyes, the coordinator of the Honduran lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender advocacy group Arcoíris (Rainbow), had spent 10 months abroad for his own safety, but felt an obligation to return to the frontline of the fight against discrimination.

“To be able to continue with my personal life and my work I have to be conscious that [death] could come at any moment,” he said. “The truth is it doesn’t worry me anymore. What worries me is that things won’t change.”

Dozens of LGBT Hondurans are murdered each year, with few of the killers brought to justice, according to figures from respected Honduran NGO Cattrachas. Journalists and activists who speak out are often attacked. One of these was Juan Carlos Cruz Andara who died after being stabbed 25 times by unknown assailants last June.

Arcoíris reported 15 security incidents against its members during the second half of 2015, including surveillance, harassment, arbitrary detentions, assaults, robberies, theft, threats, sexual assault and even murder. Other LGBT activists have experienced forced evictions, fraudulent charges, defamation, enforced disappearances and restrictions of right to assembly.

The activists consulted by Index all said that the level of homophobic violence exploded after the ousting of liberal President Manuel Zelaya in the military coup of 2009. The election of right-wing candidate Porfirio Lobo Sosa the following year coincided with the militarisation of Honduras, a rise in gang-related violence, and a clampdown on human rights.

The records from Cattrachas show that on average two LGBT people were murdered each year in the country from 1994 to 2008. After the 2009 coup that rate rocketed to an average 31 murders per year, according to figures from Arcoíris. In early 2016 there were signs the situation was escalating further with the murder of Paola Barraza, a member of Arcoiris’s group, on 24 January. In reality though it is impossible to know precisely how many people have been killed because of their sexuality because the vast majority of cases remain unsolved.

Erick Martínez Salgado, who volunteers with LGBT advocacy group Kukulcanhn, told Index that gay activists protested heavily against discrimination and the coup. He believes the government came to view his group as a threat to the traditional social order and started targeting them to “send a message” to other protesters.

One of the most prominent gay rights activists of the time, Walter Tróchez, was killed in a drive-by shooting in December 2009. Human rights groups noted that he had previously been kidnapped, beaten and threatened for demonstrating against the coup and advocating for gay rights. Four years later, Tróchez’s friend and fellow gay rights activist Germán Mendoza was arrested and charged with his murder.

Mendoza told Index he was held in deplorable conditions and repeatedly tortured in a bid to make him plead guilty. Eventually he was released after proving his innocence last year. Mendoza believes he was arrested because the government wanted to use him “as a scapegoat to wash their hands of the responsibility” for Tróchez’s death, which remains unsolved. The Honduran government did not respond to requests for comment.

Gang warfare was a massive contributor to Honduras status as the nation with the world’s highest murder rate in 2012, however the gay community’s main concern is not gangs, but the state security forces.

“The police constitute the primary perpetrator of violations of the rights of the LGBT community,” the Coalition Against Impunity, an alliance of 29 Honduran NGOs, warned last year, citing alleged “police policy of frequent threats, arbitrary arrests, harassment, sexual abuse, discrimination, torture and cruel or degrading treatment”.

As a result many vulnerable activists are reluctant to ask for protection, for fear that contact with the police would expose them to greater security risks or reprisals.

The journalists who document homophobic violence in Honduras also risk their lives. Dina Meza, an independent investigative reporter who has covered the issue extensively, was nominated for an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award in 2014 for her journalism. Meza said the country’s mainstream media often portrays the LGBT community in a negative light.

Meza, who launched the independent news site Pasos de Animal Grande last year to draw attention to the hardships facing the most vulnerable sectors of society, said reporters who cover violence against the LGBT community are also targeted. She said not only do journalists get physically assaul-ted by the security forces and expelled from public events, but they are also targets of government-led smear campaigns.

“It’s extremely common here for them to link human rights defenders to drug trafficking and organised crime, in a bid to sow doubts in people’s minds about the work that we’re doing,” she explained. “If we speak out at an international level they say we’re trying to undermine Honduras, discourage investment and see the country burn.”

Peter Tatchell, director of the London-based LGBT campaigning group the Peter Tatchell Foundation, called for the world to pay more attention to the killings. He said: “This extensive, shocking mob violence against LGBT Hondurans is almost unreported in the rest of the world. The big international LGBT organisations tend to focus on better-known homophobic repression in countries like Egypt, Russia, Iran and Uganda. What’s happening in Honduras is many times worse. Is this neglect because it is a tiny country with few resources and no geo-political weight? The UN, Organisation of American States and foreign aid providers need to do more to press the Honduran government to crackdown on anti-LGBT hate crime and to educate the public on LGBT issues to combat prejudice.”

Meza and the activists interviewed by Index also believe that Catholic and Evangelical Christian groups have become increasingly influential in Honduran society. Reyes from Arcoíris described the state, the church and the mainstream media as a triumvirate which has fuelled “impunity, fundamentalism, machismo and misogyny” across the country, with disastrous consequences for the LGBT community.

“At home and at school are the first two places where we’re attacked and discriminated. We flee home at very young ages because the family is built on religious values. Our families punish us in a cruel manner and this has a terrible psychological impact,” Reyes said. “Our educational and employment opportunities are diminished every day. We can be sex workers or street vendors, or stay in the closet in the hope of getting a job, but if they find out about your sexual orientation you’ll almost certainly be fired.”

Despite the risks he and his fellow activists face, Reyes said the drastic need for change is what gives them the strength to keep fighting discrimination: “We need a Honduras that’s free from violence and homophobia. We believe it’s our responsibility to fight for this so the next generation have a space to live in a better world.”

This article is from the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (free trial or £18 for the year). Copies are also available at the BFI and Serpentine Gallery (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.