3 Jun 2014 | Campaigns, Politics and Society

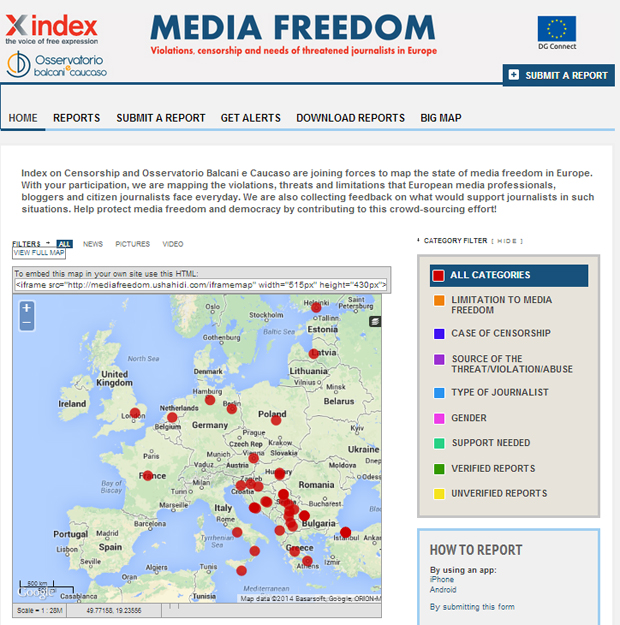

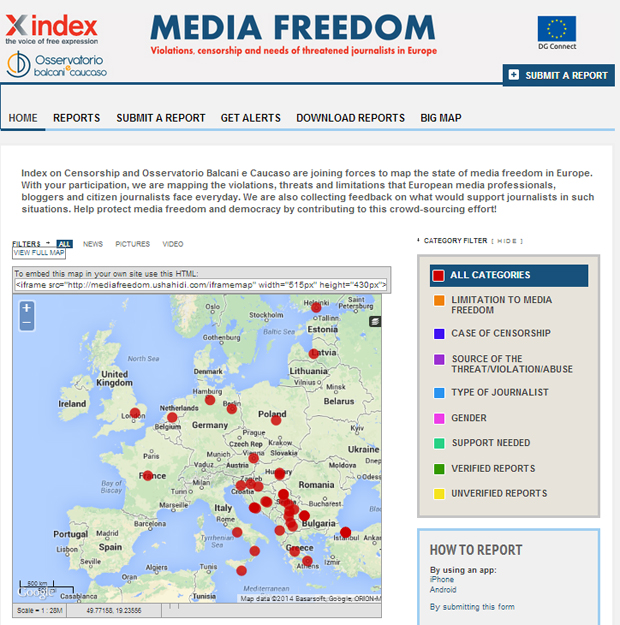

As part of its effort to map media freedom in Europe, Index on Censorship’s regional correspondents are monitoring media across the continent. Here are incidents that they have been following.

AUSTRIA

Police block journalists’ access to protest

Police denied journalists access to the site where members of the right-wing group “Die Identitären” were demonstrating on May 17. News website reports and a video from Vice News show police using excessive force against demonstrators. The Austrian Journalists’ Club described the police’s treatment of journalists as one of the recent “massive assaults of the Austrian security forces on journalists” and called for journalists to report breeches in press freedom to the club. (Austrian Journalists’ Club) (Twitter)

CROATIA

Croatian law threatens journalists

Croatia’s new Criminal Code establishes the offence of “humiliation”, a barrier to freedom of expression that has already claimed its first victim among journalists – Slavica Lukić, of newspaper Jutarnji list. A Croatian journalist is likely to end up in court and be sentenced for “humiliation” for writing that the Dean of the Faculty of Law in Osijek, Croatia’s fourth largest city, is accused by the judiciary of having received a bribe of 2,000 Euros to pass some students during an examination. For the court, it is of little importance that the information is correct – it is enough for the principal to state that he felt humbled by the publication of the news. According to Article 148 of the Criminal Code, introduced early last year, the court may sentence a journalist (or any other person that causes humiliation to others) if the information published is not considered as of public interest.

CYPRUS

Cyprus’ Health ministry Director General accused of 30million scandal whitewash

9.5.2014: The former Director General of the Ministry of Health, Christodoulos Kaisis, is alleged to have censored the responses of two ministerial departments during an audit regarding a 30 million scandal of mispricing of drugs. He did not send the requested information to the Audit Committee of the Parliament. (Politis)

DENMARK

Journalists convicted for violating law protecting personal information

On May 22 2014 two Danish journalists got convicted for violated Danish law protecting personal information because they named twelve pig farms in Denmark as sources of the spread of MRSA, a strain of drug-resistant bacteria. They argue they had been trying to investigate the spread of MRSA, but the government had wanted to keep that information secret. Their defense attorney claims revealing the names was appropriate because ‘there is public interest in openness about a growing health hazard’. The penalty was up to six months imprisonment, but the judge ruled they have to pay 5 day-fines of 500 krone (68 euro). The verdict is a ‘big step back for the freedom of press’ in Denmark, one of the journalists, Nils Mulvad said after the trial.

FINLAND

ECHR rejects journalist’s free speech claim

On April 29 2014, the European Court of Human Rights rejected a free speech claim over a defamation conviction by a Finnish journalist. In August 2006 journalist Tiina Johanna Salumaki and her editor in chief were convicted of defaming a businessman. The newspaper published a front page story, asking whether the victim of a homicide had connections with this businessman, K. U. The court ruled that Salumaki and the newspaper had to pay damages and costs to K. U. According to Salumaki her right to free expression was breached.

GERMANY

Journalist’s phone tapped by state police

A journalist’s telephone conversation with a source was tapped by state criminal police. The journalist, Marie Delhaes, spoke about the police’s subsequent contact with her on the media show ZAPP on German public television. Police asked her to testify as a witness in a criminal case against the source she communicated with, an Islamist accused of inciting others to fight with rebels in Syria. Delhaes was threatened with a fine of 1000 Euros if she were to refuse to testify. She has since claimed reporter’s privilege, protecting her from being forced to testify in a case she worked on as a journalist. (NDR: ZAPP)

Local court rules police confiscation of podcasters’ recording equipment and laptops was illegal

A court ruled on May 22 that police officers’ 2011 confiscation of recording equipment and laptops in a van used by the podcasters Metronaut and Radio Freies Wendland was illegal. The podcasters were covering the transport of atomic waste through Germany and were interviewing anti-atomic energy activists. When the equipment was confiscated, police officers also asked the podcasters to show official press passes, which they did not have. The court ruled that police failed to determine the present danger of the equipment in the van before confiscating it for three days. Metronaut later sued the police. (Metronaut) (Netzpolitik.org)

GREECE

Lost in translation

The Greek newswire service ANA-MPA is accused by its own Berlin correspondent of engaging in pro government propaganda after a translation of the official announcement by the German Chancellor regarding Angela Merkel’s Athens visit is ‘revised’, eliminating all mentions of ‘austerity,’ replacing the word with ‘consolidation’. (The Press Project)

Radio advert from pharmacists banned

A union representing pharmacists in Attica has accused the government of censorship, after it was told it may not broadcast adverts deemed by the authorities to be a political nature in the run up to elections later this month. (Eleftherotypia, English Edition)

ITALY

The regional Italian newspaper “L’ora della Calabria” is shut down due to political pressure

After the complaint, in February, against the pressures to not refer in an article to the son of senator Antonio Gentile, and to the block of the printing presses on the same day (an episode that is under investigation by the judiciary), now the newspaper L’Ora della Calabria is closing. The publications have been halted, even that of the website. This was decided by the liquidator of the news outlet, who had for a long time been in financial difficulties.

Reporter sued for criticizing the commissioner

Marilena Natale criticized a legal consultancy that cost €60’000 in the town whose City Council has dissolved for mafia, and which suffers from thirst due to the closure of the artesian wells. Ms Marilena Natale, reporter for the Gazzetta di Caserta and +N, a local all-news television channel, was sued. She had in the past already been the victim of other complaints and assaults. To denounce the journalist was Ms Silvana Riccio, the Prefectural Commissioner who administers the City of Casal di Principe, fired due to Camorra infiltrations. The Commissioner Riccio feels defamed by a series of articles written by the reporter in which the decision to spend €60’000 for legal advice is criticized, while the citizens suffer thirst due to the closure of numerous wells due to groundwater pollution.

MACEDONIA

A band to defend press freedom

24.4.2014: A music band called “The Reporters” was created recently by famous Macedonian journalists. The project aims to defend press freedom in Macedonia and support their colleagues who are facing censorship and other limitations. (Focus)

Macedonian government member encourages censorship in the press

14.5.2014: The Macedonian government quietly encourages censorship in the press, buys the silence of the media through government advertising and at the same time gives carte blanche to use hate speech, said Ricardo Gutierrez, Secretary General of the European Federation of Journalists during a conference of the Council of Europe in Istanbul on the 14th of May. (Focus)

Macedonian Journalists ‘Working Under Heavy Pressure’

24.3.2014: Sixty-five per cent of Macedonian journalists who responded to a survey publish last March, have experienced censorship and 53 per cent are practicing self-censorship, says the report, entitled the ‘White Book of Professional and Labour Rights of Journalists’. (Balkan Insight)

MALTA

The Nationalist Party complains of censorship by the public broadcaster PBS

The Nationalist Party (PN) has accused PBS of censoring it in its coverage of the European parlament elections campaign. The party noted that PBS did not send a journalist to report on Simon Busuttil’s visit to Attard and Co on Tuesday and it had also failed to sent a reporter to cover a press conference addressed by PN Secretary General Chris Said in Gozo this morning. “This is nothing but censorship during an electoral campaign,” the PN said. The PN has also complained with the national TV station on its choice of captions for news items carried in the bulletin.

NETHERLANDS

Press photographers’ equipment seized

During a raid on a trailer park in Zaltbommel on may 27 2014, the cameras of two press photographers were seized by the police. According to the spokesman of the court of Den Bosch the police took the cameras after several warnings. The photographers were on the public road. After a few days the two photographers got their cameras back, but their memory cards with the photo’s are still not returned. The NVJ, de Dutch journalist Union, has pledged to stand with one of the journalists in his claim to get his photo’s back.

SERBIA

Serbia Floods Interrupt Free Flow of News

Websites criticising the government’s handling of the flood disaster in Serbia have come under attack from hackers in what some call a covert act of censorship. Creators of the Serbian blog Druga Strana, which published critical posts on the Serbian state’s handling of the flooding, were forced to shut it down on Tuesday after repeat attacks on the site. “The site has been under heavy attack so we decided to shut it down in order not to compromise other sites on the server,” Nenad Milosavljevic said.

Serbian Newspaper Editor Fired After Criticising Govt

The sacking of Srdjan Skoro, editor of state-owned newspaper Vecernje Novosti, who publicly criticized Serbia’s new ministers, has been described as an attack on independent media. Skoro said that he was told that he was no longer the editor of the Serbian tabloid Vecernje Novosti on Friday morning, but was given no explanation for his sacking. “I have been told to find another job and that I would perhaps do better there,” Skoro said. He said that although no one has said it directly, the reason for his dismissal was his recent appearance on public service broadcaster RTS’s morning TV show, in which he openly criticised some candidates for posts in the new Serbian cabinet.

SERBIA

Media in Serbia: the government’s double standard

Aleksandar Vučić’s government seems to be adopting a double standard when it comes to media: one for the EU, one for Serbia, with tight control over newspapers and television stations. I do not believe in chance, and I know “where all this is coming from and who is behind it”. Thus Aleksandar Vučić, Prime Minister of Serbia, commented the statement by Michael Davenport, head of the EU Delegation, about “unpleasant and unacceptable” issues in Serbian media. Davenport said that elements of investigations conducted by the judiciary are leaked to the public through some media, and that the “cases” of parallels being made between representatives of civil society and crime are “a clear violation of the ethical standards of the media”.

SLOVENIA

If you can’t stand the heat, don’t turn up the oven: Strasbourg Court expands tolerance for criticism of xenophobia to criticism of homophobia

On the 17th of April 2014, the European Court of Human Rights issued a judgement in the case of Mladina v. Slovenia. In this case, the Court further develops its standing case law on “public statements susceptible to criticism”. When assessing defamation cases, the Court has in the past found that authors of such statements should show greater resilience when offensive statements are in turn addressed to them.

SPAIN

The government threats to censor social media

“We have to combat cybercrime and promote cybersecurity, and to clean up undesirable social media.” These were the words of the Spanish Minister of Interior, Jorge Fenández Díaz, after the wave of comments published on social media about the assassination of Isabel Carrasco, president of the Province of León and member of the government party (Pp). Although the majority expressed their condolences to the family of the victim, there were some that took advantage of the moment to openly criticize the politician, including mocking her assassination. These tweets generated a strong reaction of rejection in certain circles. For their part, Tweeters have reacted by creating two hashtags, #TuiteaParaEvitarElTalego (Tweet to stay out of Jail) y #LaCárcelDeTwitter [Twitter Prison], through which many Internet-users vent their frustration against politicians who want to silence them. On the other hand the Federal Union of Police has published a note that proposes a change in legislation with the alleged intent of protecting minors, relatives of victims, and users in general.

Extremadura public television don’t broadcast the motion of censure on the regional president Monago

Extremadura public television did not broadcast the debate and subsequent vote of no confidence on the regional president and member of the government party Antonio Monago on May 14th, despite the political relevance of the issue (the debate was broadcasted only trough the TV’s website). The workers called a protest to consider a motion of censure “is a matter of highest public interest and should be covered by public broadcast media in all its channels”, as expressed by the council in a statement.

TURKEY

Founder of satirical website sentenced for discussion thread considered insulting to Islam

The founder of the satirical online forum Ekşi Sözlük was given a suspended sentence of ten months in prison. Forty authors for the user-generated website were detained in connection to a complaint that a thread in an Ekşi Sözlük forum was insulting to Islam. Founder Sedat Kapanoğlu and another defendant received suspended prison sentences for insulting religious values. (Hürriyet Daily News)

Journalists recently released from prison speak out against government using release for political capital

Journalists who had been imprisoned for two years in connection to the KCK case were released this month. Several of the released journalists gave a press conference on May 13 condemning the government’s manipulation of the case to improve its own human rights and press freedom standing internationally. Yüksek Genç, a journalist who spoke at the press conference, said that the amount of journalists in prison can not be the only measure of Turkey’s press freedom, since the government has other ways of meddling in media and putting economic pressure on news organisations. A number of journalists have been released from prison this year after a court regulation was changed, enforcing a shorter maximum detention time for prisoners awaiting trial on terrorism charges. (Bianet)

Police detain and injure journalists at May 1 protests

During May Day protests in Istanbul, police blocked journalists’ access to demonstrating crowds and demanded they show official press passes to enter the area around Taksim Square. At least 12 journalists were injured by police officers using rubber bullets, teargas and bodily force. Deniz Zerin, an editor of the news website t24, was detained trying to enter his office and held for three days. (Bianet)

Prominent journalist sentenced to ten months in prison for tweet insulting Prime Minister Erdoğan

On April 28, the journalist Önder Aytaç was sentenced to ten months in prison for a 2012 tweet that the court ruled to be insulting to Turkish Prime Minister Erdoğan under blasphemy laws. The tweet included a word that translates to “my chief” or “my master” (relating to Erdoğan), but included an additional letter at the end that made the word vulgar. Erdoğan sued Aytaç, who maintained that the extra letter in his tweet was a typo. (Medium)

For more reports or to make your own, please visit mediafreedom.ushahidi.com.

With contributions from Index on Censorship regional correspondents Giuseppe Grosso, Catherine Stupp, Ilcho Cvetanoski, Christina Vasilaki, Mitra Nazar

This article was posted on June 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 May 2014 | Czech Republic

Peter Demetz (Photo: Prague Book Fair)

Emeritus Yale University professor and author Peter Demetz was awarded the Jiri (George) Theiner prize at the Prague Literary Festival this year.

George’s son Pavel, the prize organiser, said Demetz received the award because “all his life he has remained intellectually honest in his demystification of views which sometimes became popular such as the notion of magical Prague, rather stressing the reality of Czech history, as well as his life-long commitment to Czech literature in American and German environments and as translator of Frantisek Halas´ and Jiri Orten´s poetry”.

Theiner set up the prize in memory of his father’s work, as a former editor of Index on Censorship magazine he brought attention to Czech writing and writers during the communist era. He said: “Almost five years ago I discussed with the director of World of Books (Prague Book Fair), Dana Kalinova, the possibility of making this prize an important permanent fixture at the annual book fair. Looking back I realised that George Theiner´s reputation here was as solid as it was in other countries, despite the fact that he left in 1968.

The jury this year was chaired by Lenka Jungmannova (professor at the Institute of Czech Literature, Academy of Sciences), Martin Putna (literary historian, professor at Prague´s Charles University and critic), Jiri Gruntorad (guardian of the largest samizdat collection in central and eastern Europe, dissident persecuted in the 1970´s and 1980´s) and Ivan Biel (documentary film-maker and lecturer in Film Studies). Next year’s jury was also announced and will include Karel Schwarzenberg (a former Czech foreign minister, one of Havel´s closest aides and supporter of dissidents before 1989 whilst living in Austria), Michal Priban (academic at the Institute of Czech Literature, Academy of Sciences), Vladimír Pistorius (samizdat publisher who successfully made the transition into becoming a ´straight´ book publisher) and Jan Bednar (radio journalist and commentator, signatory of Charter 77, between 1985 and 1992 and who worked for the BBC in London).

Theiner said that they received between 35 and 60 nominations each year from all over the world. The criteria stated that the recipient (or organisation) had made a major long-term contribution to the promotion of Czech literature overseas, with an expectation that they have also made a contribution to freedom of speech and human rights in general. Other prize winners include Andrzej Jagodzinski, translator of Havel, Hrabal, Kundera, journalist as well as a leading member of the democratic opposition on Poland); Ruth Bondy (an Israeli of Czech origin, survivor of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen who worked as a journalist on the Hebrew daily Davar; and Paul Wilson (a Canadian who lived in Czechoslovakia as a young man before being thrown out in 1977 for collaborating with dissidents and, above all, the band Plastic Pepople of the Universe, translator of Skvorecky, Klima, Havel, Hrabal, radio producer, editor and writer).

Theiner said: “One of the most positive aspects that has come out of the activity surrounding the prize has been the link made between old and new Index on Censorship. It was a real joy to welcome to Prague at the first prize-giving the founding editor Michael Scammell along with some of his old colleagues such as Philip Spender, Haifaa Khalafallah and others. Four years later the present editor Rachael Jolley joined us and moderated a discussion following the award-giving ceremony on freedom after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a reflection on the democratisation of society and freedom of expression in literature and journalism. It´s great to see that the bridge-building that George Theiner was so adept at is still going strong.”

This article was published on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

9 Apr 2014 | Digital Freedom, European Union, News and features

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Retaining data is the reflex of a functioning bureaucracy. What is stored, how it is stored, and when it is disseminated, poses the great trinity of management. These principles lurk, ostensibly at least, under an umbrella of privacy. The European Union puts much stake in Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, stressing the values of privacy that covers home, family and correspondence. But there are also wide qualifications – interferences are warranted in the interest of national security and public safety, allowing Member States, and the EU, a degree of room to gnaw away at privacy rights.

That entitlement to privacy has gradually diminished in favour of the “security” limb of Article 8. The surveillance narrative is shaping privacy as a necessarily circumscribed right. The realm of monitoring and surveillance is being extended. Technologies have proliferated; laws have remained, if not stagnant, then ineffective.

Unfortunately for those occasionally oblivious drafters of rules in Brussels, the judges of the Court of Justice of the EU did not take kindly to the Data Retention Directive, which requires telecommunications and internet providers to retain traffic and location data. That is not all – the directive itself also retains data identifying the user or subscriber, a true stab against privacy proponents keen on principles of anonymising users.

The objective of the DRD, like so many matters concerned with bureaucratic ordering, is procedural: to harmonise regimes of data retention across various member states. More specifically, Directive 2006/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of March 15 2006 deals with “retention of data generated or processed in connection with the provision of publicly available electronic communications services or of public communications networks”.

Other courts have expressed concern with the directive, which propelled the hearings to the ECJ. These arose from separate complaints in Ireland and Austria over measures taken by citizens and parties against the authorities. The Irish case began with a challenge by Digital Rights Ireland in 2006. The Austrian legal challenge was pushed by the Kärntner Landesregierung (Government of the Province of Carinthia) and numerous other concerned parties to annul the local legislation incorporating the directive into Austrian law.

The Constitutional Court of Austria and the High Court of Ireland shook their judicial fingers with rigour against it – the judges were not pleased. The disquiet continued to their brethren on the ECJ, which proceeded to make its stance on the scope of the retention law clear by declaring it invalid. EU officials should have seen it coming – in December last year, the Advocate General of the ECJ was already of the opinion that the DRD constituted “a serious interference with the privacy of those individuals” and a “permanent threat throughout the data retention period to the right of citizens of the Union to confidentiality in their private lives.”

The defensive stance taken by the authorities is so old it is gathering dust. Technology changes, but government rationales never do. Invariably, it is two pronged. The ever pressing concerns of security forms the first. The second: that such behaviour does not violate privacy – at least disproportionately. You will find these principles operating in tandem in each defence on the part of authorities keen to justify extensive data retention. Such intrusive measures have as their object the gathering of information, rather than the gathering of useful data. The usefulness is almost never evaluated as a criterion of extending the law. Instinct, not evidence, is what counts.

The rationale of the first premise is simple enough: information, or data, is needed to fight the shady forces of crime and terrorism. Better data retention practices equates to more solid defence against threats to public security. The ECJ acknowledged the reason as cogent enough – that data retention “genuinely satisfies an objective of general interest, namely, the fight against serious crime and, ultimately, serious security.” The authorities were also keen to emphasise that such a regime of retention was not “such as to adversely affect the essence of the fundamental rights to respect for private life and to the protection of private data.”

In dismissing the main arguments of the authorities, the points of the court are clear. In retaining the data, it is possible to “know the identity of the person with whom a subscriber or registered user has communicated and by what means”. Identification of the time of the communication and place form which that communication took place is also possible. Finally, the “frequency of the communications of the subscriber or registered user with certain persons during a given period” is also disclosed. Taken as a whole set, these composites provide “very precise information on the private lives of the persons whose data are retained, such as the habits of everyday life, permanent or temporary places of residence, daily or other movements, activities carried out, social relationships and the social environments frequented.” Former Stasi employees would be swooning.

The judgment provides a relentless battering of a directive that should never left the drafter’s desk. “The Court takes the view that, by requiring retention of those data and by allowing competent national authorities to access those data, the directive interfered in a particularly serious manner with the fundamental rights to respect for private life and to the protection of personal data.”

The laws of privacy tend to focus on specificity and limits. If there is to be interference, it should be proportionate. The directive had failed at the most vital hurdle – if privacy is to be interfered with, do so in even measure with minimal interference. The DRD had, in effect “exceeded the limits imposed by compliance with the principle of proportionality.” The decision is unlikely to kill off regimes of massive data retention – it will simply have to make those favouring surveillance over privacy more cunning.

This article was posted on April 9, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Politics and Society

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Collectively, the European Union of 28 member states has an important role to play in the promotion of freedom of expression in the world. Firstly, as the world’s largest economic trading block with 500 million people that accounts for about a quarter of total global economic output, it still has significant economic power. Secondly, it is one of the world’s largest “values block” with a collective commitment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and perhaps more significantly, the European Convention on Human Rights. The Convention is still one of the leading supranational human rights treaties, with the possibility of enforcement and redress. Finally, Europe accounts for two of the five seats on the UN Security Council (Britain and France), so has a crucial place in the global security framework. The EU itself has limited foreign policy and security powers (although these powers have been enhanced in recent years), leaving significant importance to the foreign policies of the member states. Where the EU acts with a common approach it has leverage to help promote and defend freedom of expression globally.

How the European Union supports freedom of expression abroad

The European Union has a number of instruments and institutions at its disposal to promote freedom of expression in the wider world, including its place as an observer at international fora, its bilateral and regional agreements, the European External Action Service (EEAS) and geographic policies and instruments including the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) and the European Neighbouring and Partnership Instrument (ENPI). The EU places human rights in its trade and aid agreements with third party countries and has over 30 stand-alone human rights dialogues. The EU also provides financial support for freedom of expression through the European Development Fund (EDF), the Development Co-operation Instrument (DCI), the European Instrument for democracy and human rights (EIDHR) and the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). The EU now also has a Special Representative for Human Rights. Since 1999, the EU has published an annual report on human rights and democracy in the world. The latest report, adopted in June 2012, contains a special section on freedom of expression, including freedom of expression and “new media”. It recalls the EU’s commitment to “fight for the respect of freedom of expression and to guarantee that pluralism of the media is respected” and emphasises the EU’s support to free expression on the internet.

The European Union has two mechanisms to financially support freedom of expression globally: the European Instrument for democracy and human rights (EIDHR) and the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). The latter was specially created after the Arab Spring in order to resolve specific criticism of the EIDHR: that it didn’t support political parties, non-registered NGOs and trade unions and could not react quickly to events on the ground. The EED is funded by, but is autonomous from, the European Commission, with support from member states and Switzerland. The aims of the EED, to provide rapid and flexible funding for pro-democratic activists in authoritarian states and democratic transitions, is potentially a “paradigm shift” according to experts that will have to overcome a number of challenges, in particular a hesitation towards funding political parties and the most active and confrontational of human rights activists. The EU also engages with the UN on human rights issues at the Human Rights Council (HRC) and in the 3rd Committee of the General Assembly. The EU, as an observer along with its member states, is one of the more active defenders of freedom of expression in the HRC. Promoting and protecting freedom of expression was one of the EU’s priorities for the 67th Session of the UN General Assembly (September 2012-2013). The European Union was also instrumental in the adoption of a resolution on the “Safety of Journalists” (drafted by Austria) in September 2012. The European Union is most effective at the HRC where there is a clear consensus among member states within the Union . Where there is not, for instance on the issue of blasphemy laws, the Union has been less effective at promoting freedom of expression.

The EU and its neighbourhood

The EU has had mixed success in promoting freedom of expression in its near neighbourhood. Enlargement has clearly been one of the European Union’s most effective foreign policy tools. Enlargement has had a substantial impact both on the candidate countries’ transition to democracy and respect for human rights. With enlargement slowing, the leverage the EU has on its neighbourhood is under pressure. Alongside enlargement, the EU engages with a number of foreign policy strategies in its neighbourhood, including the Eastern Partnership and the partnership for democracy and shared prosperity with the southern Mediterranean. This section will look at the effectiveness of these policies and where the EU can have influence.

The EU and freedom of expression in its eastern neighbourhood

Europe’s eastern neighbourhood is home to some of the least free places for freedom of expression. The collapse of the former Soviet Union and the enlargement of the European Union has significantly improved human rights in eastern Europe. There is a marked difference between the leverage the European Union has on countries where enlargement is a real prospect and the wider eastern neighbourhood, where it is not, in particular for Russia and Central Asia. In these countries, the EU’s influence is more marginal. Enlargement has clearly had a substantial impact both on the candidate countries’ transition to democracy and their respect for human rights because since the Treaty of Amsterdam, respect for human rights has been a condition of accession to the EU. In 1997, the Copenhagen criteria were outlined in priorities that became “accession partnerships” adopted by the EU and which mapped out the criteria for admission to the EU. They related in particular, to freedom of expression issues that needed to be rectified. With the enlargement process slowing since the “big bang” in 2004, and countries such as Ukraine and Moldova having no realistic prospect of membership regardless of their human rights record, the influence of the EU is waning in the wider eastern neighbourhood.

After enlargement, the Eastern Partnership is the primary foreign policy tool of the European Union in this region. Launched in 2009, the initiative derives from the EU’s Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which is specific about the importance of democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights. In this region, the partnership covers Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Freedom of expression has been raised consistently during human rights dialogues with these six states and in the accompanying Civil Society Forum. The Civil Society Forum has also been useful in helping to coordinate the EU’s efforts in supporting civil society in this region. Although it has never been the main aim of the Eastern Partnership to promote freedom of expression, it has had variable success in promoting this right with concrete but limited achievements in Belarus, the Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova; with a more ineffectual role being seen in Azerbaijan.

In recent years, since the increased input of the EEAS in the ENP, the policy has become more markedly political, with a greater emphasis on democratisation and human rights including freedom of expression after a slow start. In particular, freedom of expression was raised as a focus for the ENP after its review in 2010-2011. This is a welcome development, in marked contrast to the technical reports of previous years. This also echoes the increased political pressure from member states that have been more public in their condemnation of human rights violations, in particular regarding Belarus. Belarus is one Eastern Partnership country where the EU has exerted a limited amount of influence. The EU enhanced its pressure on the country after the post-presidential election clampdown beginning in December 2010, employing targeted sanctions and increasing support to civil society. This has arguably helped secure the release of some of the political prisoners the regime detained. Yet the lack of a strong sense of strategy and unity within the Union has hampered this new pressure to deliver more concrete results. Likewise, the EU’s position on Ukraine has been set back by internal divisions, even though the EU’s negotiations on the Association Agreement included specific reference to freedom of expression.

In Azerbaijan, the EU’s strategic oil and gas interests have blunted criticism of the country’s poor freedom of expression record. Azerbaijan holds over 89 political prisoners, significantly more than in Belarus, yet the EU’s institutions, individual member states and European politicians have failed to be vocal about these detentions, or other freedom of expression violations. In the EU’s wider neighbourhood outside the Eastern Partnership, the EU has taken a less strategic approach and accordingly has been less successful in either raising freedom of expression violations or helping to prevent them.

The European Union’s relationship with Russia has not been coherent on freedom of expression violations. While the institutions of the EU have criticised specific freedom of expression violations, such as the Pussy Riot sentencing, they were slow to criticise more sustained attacks on free speech such as the clampdown on civil society and the inspections of NGOs using the new Foreign Agents Law. The progress report of EU-Russia Dialogue for Modernisation fails to mention any specific freedom of expression violations in Russia. The EU has also limited its financial involvement in supporting freedom of expression in Russia, unlike in other post-Soviet states. The EU is not united on this criticism: individual European Union member states such as Sweden and the UK are more sustained in their criticisms of Russia’s free speech violations, whereas other member states such as Germany tend to be less critical. It is argued that Russia’s powerful economic interests have facilitated a significant lobbying operation including former politicians that works to reduce criticism of Russia’s freedom of expression violations.

In this region, the European Union’s protection of freedom of expression is weakest in Central Asia. While the EU has human rights dialogues with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, it has not acted strategically to protect freedom of expression in these countries. The EU dramatically reduced its leverage in Uzbekistan in 2009 by relaxing arms sanctions with little in return from the Uzbek authorities, who continue to fail to abide by international human rights standards. Arbitrary arrests, beatings and torture at the hands of the security services, as well as unfair trials of the regime’s critics are all commonplace. The European Parliament’s special rapporteur report of November 2012, took a tough stance on human rights in Kazakhstan, making partnership conditional on respect for Article 10 rights. But, this was undermined by High Representative Baroness Ashton’s visit to the country in November 2012, where she failed to raise human rights violations at all.

This lack of willingness to broach freedom of expression issues continued during Baroness Ashton’s first official visit to four of the five Central Asian republics: Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan. In Kyrgyzstan she additionally attended an EU-Central Asia ministerial meeting, where the Turkmen government (one of the top five most restrictive countries in the world for freedom of expression) was represented. Baroness Ashton’s lack of vocal support for human rights was condemned by local NGOs and international watchdogs.