16 Dec 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.04 Winter 2016

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row” full_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1481647350516{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/magazine-cover-subhead.jpg?id=82616) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Governments that introduce bans on clothing and other forms of expression are sending a signal about their own lack of confidence” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

IF YOU HAVE to introduce laws telling your citizens that they are banned from wearing purple, sporting red velvet, or showing their knees, then, frankly, you are in trouble.

But again and again, when times get tough or leaders think they should be, governments tell their people what to wear, or more often, what not to wear.

“Dare to wear this,” they say, “and we will be down on you like a ton of bricks.” Why any government thinks this is going to improve their power, the economy or put their country on a better footing is a mystery. History suggests you never strike up a more profitable relationship with your people by removing the freedom to wear specific types of clothing or, conversely, telling everyone that they have to wear the same thing. We are either consumed by rebellion, or by dullness.

The Romans tried it with purple (only allowed for the emperor and his special friends). The Puritans tried it with gold and silver (just for the magistrates and a few highfaluting types). Right now the governments of Saudi Arabia and Iran ban women from wearing anything but head-to-toe cover-ups along with a range of other limitations. In one frightening case in the past month there were calls via social media for a woman in Saudi Arabia to be killed because she went out shopping “uncovered” without a hijab or abaya. One tweet read: “Kill her and throw her corpse to the dogs.”

Banning any type of freedom of expression, often including free speech, or freedom of assembly, usually happens in times of national angst, economic downturn or crisis, when governments are not acting either in the interest of their people, or the national good. These are not healthy, confident nations, but nations that fear allowing their people to speak, act and think. And that fear can express itself in mandating or restricting types of expression. Generally, as with other restrictions on freedom found in the US First Amendment, enforcing such bans doesn’t sweep in a period of prosperity for countries that impose them.

At different points in world history governments have forced a small group of people to wear particular things, or tried to wipe out styles of clothing they did not approve of. In medieval Europe, for instance, non-Christians were, at certain periods, forced to wear badges such as stars or crescents as were Christians who refused to conform to a state religion, such as the Cathars. Forcing a particular badge or clothing to be worn sends a signal of exclusion. Those authorities are, by implication, saying to the majority that there is a difference in the status of the minority, and in doing so opening them up either to attack, or at least suspicion. Not much has changed between then and now. Historically groups that have been forced to wear some kind of badge or special outfit have then found themselves ostracised or physically attacked. The most obvious modern example is Jews being forced to wear yellow stars in Nazi Germany, but this is not the only time minorities have been legally forced to stand out from the crowd. In 2001 the Taliban ruled that Afghan Hindus had to wear a public label to signify they were non-Muslims. The intent of such actions are clear: to create tension.

The other side of this clothing coin is when clans, tribes or groups who choose to dress differently from the mainstream, for historical religious reasons, or even just because they follow a particular musical style, are persecuted because of that visual difference, because of what it stands for, or because they are seen as rebelling against authority. In some cases strict laws have been put in place to try and force change, in other cases certain people decide to take action. In 1746, for instance, the British government banned kilts and tartans (except for the military) under the Dress Act, a reaction said to be motivated by support for rebellions to return Catholic (Stuart) monarchs to the British throne. Those who ignored the order faced six months in prison for the first instance, and seven years deportation for the second. Those who wear distinctive, and traditional clothing, out of choice can face other disadvantages. For years, the Oromo people in Ethiopia, who wear distinctive clothing, have long faced discrimination, but in 2016 dozens of Oromo people were killed at a religious festival, after police fired bullets into the crowd. And in her article Eliza Vitri Handayani reports on how the punk movement in Indonesia has attracted animosity and in one case, Indonesian police seized 64 punks, shaved their heads and forced them to bathe in a river to “purify themselves”. Recently the Demak branch of Nadhlatul Ulama, Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation, has banned reggae and punk concerts because they make young people “dress weird”.

Another cover for restrictions or bans stems from religions. As soon as the word “modesty” is bandied around as a reason for somebody to be prohibited from wearing something then you know you have to worry. Strangely, it is never the person who proclaims that there needs to be a bit more modesty who needs to change their ways. Of course not. It is other people who need to get a lot more modest. The inclusion of modesty standards tends to be used to get women to cover up more than they have done.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”When freedom of expression is quashed, it usually finds a way of squeezing out just to show that the spirit is not vanquished” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Then you get officious types who decide that they have the measure of morality, and start hitting women wearing short skirts (as is happening right now in South Africa and Uganda). For some Ugandan women it feels like a return to the 1970s under dictator Idi Amin “morality” laws.

Trans people can find themselves confronting laws, sometimes centuries old, that lay out what people shouldn’t be allowed to wear. In Guyana a case continues to edge through the court of appeal this year, it argues that a cross-dressing law from 1893 allows the police to arrest or harass trans people. A new collection, the Museum of Transology, which opens in London in January, uses a crowdsourced collection of objects and clothing to chart modern trans life and its conflicts with the mainstream, from a first bra to binders.

When freedom of expression is quashed, it usually finds a way of squeezing out just to show that the spirit is not vanquished. So during the tartan ban in the 18th century, there are tales of highlanders hiding a piece of tartan under other clothes to have it blessed at a Sunday service. And certainly tartan and plaids are plentiful in Scotland today. In the 1930s and 40s when British women and girls were not “expected” to wear trousers or shorts, some bright spark designed a split skirt that could be worn for playing sport. It looked like a short dress (therefore conforming to the accepted code), but they were split like shorts allowing girls to run around with some freedom.

While in Iran, where rules about “modest” dress are enforced viciously with beatings, sales of glitzy high heels go through the roof. No one can stop those women showing the world their personal style in any way they can. Iranian model and designer Tala Raassi, who grew up in Iran, has written about how vital those signs of style are to Iranian women. In a recent article, commenting on the recent burkini ban in France, Raassi wrote of her disappointment that a democratic country would force an individual to put on or take of a piece of clothing. She added: “Freedom is not about the amount of clothing you put on or take off, but about having the choice to do so.”

And that freedom is the clearest sign of a healthy country. We must support the freedom for individuals to make choices, even if we do not agree with them personally. The freedom to be different, if one chooses to be, must not be punished by some kind of lower status or ostracism. National leaders have to learn that taking away freedom of expression from their people is a sign of their failure. Countries with the most freedom are the ones that will historically be seen as the most successful politically, economically and culturally.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine. She recently won the editor of the year (special interest) at British Society of Magazine Editors’ 2016 awards

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”86201″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422016643039″][vc_custom_heading text=”T-shirted turmoil” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422016643039|||”][vc_column_text]April 2016

Vicky Baker looks at why slogan shirts are more than a fashion statement and sometimes provoke fear within great state machines.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89180″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220600624127″][vc_custom_heading text=”Miniskirts” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064220600624127|||”][vc_column_text]February 2006

Salil Tripathi believes the press should not pick and choose what to publish based on who will get offended. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90622″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228908536934″][vc_custom_heading text=”List to the right ” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228908536934|||”][vc_column_text]July 2001

UK’s Terrorism Act 2000 is further evidence of the government’s indifference to fundamental freedoms – clothing included.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fashion Rules” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F12%2Ffashion-rules%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear.

In the issue: interviews with Lily Cole, Paulo Scott and Daphne Selfe, articles by novelists Linda Grant and Maggie Alderson plus Eliza Vitri Handayani on why punks are persecuted in Indonesia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/12/fashion-rules/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Dec 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 45.04 Winter 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Contributors include Lily Cole, Daphne Selfe, Linda Grant, Bibi Russell, Katy Werlin, Jang Jin-sung, Maggie Alderson and Eliza Vitri Handayani”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear. But it also looks at how women in particular have their freedom of expression curtailed by rigid dress codes – whether they are women in Saudi Arabia who have to wear abayas by law or women in the UK and Canada whose employers insist they wear high heels shoes.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Models Lily Cole and Daphne Selfe discuss why changes in society are reflected in the clothes we (are allowed) to wear. Maggie Alderson, former editor of Elle describes how she was arrested for being a punk rocker in the 1970s, while Eliza Vitri Handayani talks about how punks in Indonesia today are still persecuted for what they wear and how they look. Nigerian model and journalist Wana Udobang riffs on fashion in Nigeria and how she was snubbed by bouncers and waiters at a wedding for wearing the wrong clothes.

Ismail Einashe describes how traditional dress can be life-threatening for Oromos in Ethiopa, while Magela Baudoin delves into class and ethnic gradations in Bolivia and reveals that the way some women dress means they are discriminated against. Novelist Linda Grant describes how her Jewish immigrant parents used the way they dressed to try and fit into middle-class British society. Meanwhile Katy Werlin gives a historical perspective as she discusses how the 18th century French revolutionaries, known as sans-culottes, celebrated their peasant clothes as they overthrew the aristocratic regime.

Martin Rowson brings another perspective to fashion in his new cartoon which depicts a catwalk on which despots show off their latest costumes. Spot President-elect Donald Trump sporting a furry thong. Trump is also in US media expert Eric Alterman’s sights as he describes why journalists in the USA believe the new president will seek to challenge media freedoms guaranteed by the constitution. Turkish researchers Burak Bilgehan Özpek and Başak Yavcan investigate how the Turkish government is using state advertising to control the media.

We also publish an interview with Turkish intellectual, linguist and founder of a mathematics village Sevan Nişanyan. Our reporter communicated with him using notes smuggled out from the prison where he is serving a 16-year sentence on charges connected with freedom of speech. The culture section includes poems from a former North Korean propagandist Jang Jin-sung who defected to the South and now runs a website smuggling news out of North Korea. We also carry poems about the extraordinariness of everyday life from Brazilian author Paulo Scott and a never before seen English translation of a short story by legendary Argentine writer Haroldo Conti.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: FASHION RULES” css=”.vc_custom_1481731933773{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Dressing to oppress: why dress codes and freedom clash

The censors’ new clothes, by Rachael Jolley: Freedom is not about the amount of clothing you put on or take off, but about having the choice to do so

Fashion police, by Natasha Joseph: Some feel the miniskirt is a threat to the state in Uganda and women are getting attacked for wearing it

Wearing a T-shirt got me arrested, by

Maggie Alderson: Wearing punk clothes in 1970s London was dangerous, but now British teenagers can wear anything

Colour bars, by Magela Baudoin: Traditional clothing is still a sign of social status in Bolivia and wearing such clothes often leads to discrimination

Models of freedom, by Bibi Russell: Bangladeshi women are now vital to the economy but they are still restricted in their dress

The big cover-up, by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Women in Saudi Arabia and Yemen test how far they can customise what they are allowed to wear. Translation by Lucinda Byatt

Rebel with a totally fashionable cause, by Wana Udobang: A Nigerian model refuses to conform to stifling social expectations and sees the consequences

Stripsearch cartoon, by Martin Rowson: A fetching new range of despotwear

Ethiopia in crisis, closes down news, by Ismail Einashe The Oromo people use traditional clothing as a symbol of resistance and it is costing them their lives

Baggy trousers are revolting

, by Katy Werlin: The sans-culottes of the French revolution transformed peasant dress into a badge of honour

Muslim punks in mohawks attacked, by Eliza Vitri Handayani: Punks in Indonesia are persecuted but still manage to maintain a culture which stands up for difference

Design is the limit, by Jemimah Steinfeld: China is loosening up on personal freedoms including fashion, but designers still face some constraints

A modest proposal, by Kaya Genç: “Modest” dress codes are all the rage in Turkey as some turn their backs on the legacy of Atatürk

Uniformity rules, by Jan Fox: Prisoners often try to customise their uniforms but does stripping individuality make rehabilitation more difficult?

Keeping up appearances, by Linda Grant: Linda Grant’s immigrant family were upwardly mobile and bought clothes that showed their aspirations

Sewing it up, by Rachael Jolley: At 88 Daphne Selfe is Britain’s oldest supermodel. She talks about how fashion has changed in her lifetime

Style counsels, by Kieran Etoria-King: Model, activist and actor Lily Cole talks about how school girls customise their uniforms to give them a sense of individuality

Tall stories, by Sally Gimson: Wearing high heels is a way for some women to express freedom, while for others it’s a form of oppression

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Challenging media, by Eric Alterman: If his campaign is anything to go by, President Trump is likely to restrict freedom of the press

Living in limbo, by Marco Salustro: A journalist reveals the challenges of reporting from inhumane migrant detention camps in Libya

Follow the money, by

Burak Bilgehan Özpek and Başak Yavcan: The Turkish government is rewarding newspapers which favour its position with more state-sponsored advertising

Fighting for our festival

freedoms, by Peter Florence: Mutilated bodies, petitions and a citizen’s arrest: the director of the Hay literary festivals describes the trials and tribulations of his job

Barring the bard, by Jennifer Leong: Actor Jennifer Leong on confronting attempts to censor performances of Shakespeare around the world

Assessing Correa’s free

speech heritage, by Irene Caselli: The Ecuadorian president’s record on free speech is reviewed as his term in office comes to an end. He gave sanctuary to Wikileaks founder, Julian Assange, in the country’s London embassy but brought in restrictive media laws at home

Framed as spies, by Steven Borowiec: South Korean journalist Choi Seung-ho hit a national nerve when he exposed the security services for framing ordinary citizens as North Korean spies

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Back from the Amazon, by

Paulo Scott: Newly translated poems from Scott’s acclaimed collection, Even Without Money I Bought a New Skateboard. Interview by Kieran Etoria-King. Poems translated by Stefan Tobler

A story from the disappeared, by Haroldo Conti: Jon Lindsay Miles introduces a poignant short story, published in English for the first time, by the award- winning Argentine writer who disappeared in 1976. Translation also by Jon Lindsay Miles

Poems for Kim, by Jang Jin-sung: North Korean propagandist poet turned high profile defector talks about life within the world’s most secretive country. Interview by Sybil Jones

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: Face-to-face encounters are still important and governments worldwide know that restricting travel continues to be an effective way of stifling voices

Index around the world, by

Kieran Etoria-King: Coverage of Index’s work over the last few months including exposing the difficulties of war reporting and our Mapping Media Freedom project

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Where’s our president? by

Kiri Kankhwende: Malawi’s journalists tease their president as part of a campaign to make the government more transparent

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Jan 2016 | Campaigns, Europe and Central Asia, France, mobile, Statements

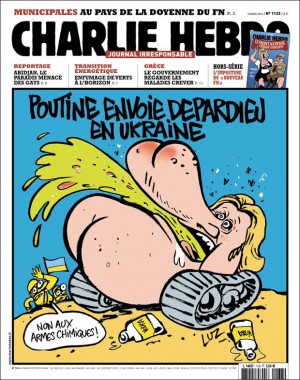

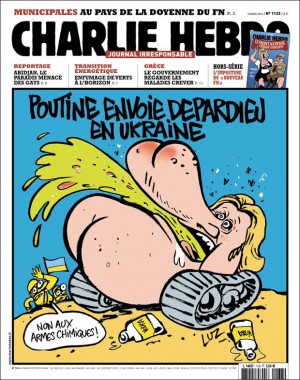

On the anniversary of the brutal attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to the defence of the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that some may consider offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack, which left 11 dead and 12 wounded, was a horrific reminder of the violence to which journalists, artists and other critical voices are subjected in a global atmosphere marked by increasing intolerance of dissent. The killings inaugurated a year that has proved especially challenging for proponents of freedom of opinion.

Non-state actors perpetrated violence against their critics largely with impunity, including the brutal murders of four secular bloggers in Bangladesh by Islamist extremists, and the killing of an academic, M M Kalburgi, who wrote critically against Hindu fundamentalism in India.

Despite the turnout of world leaders on the streets of Paris in an unprecedented display of solidarity with free expression following the Charlie Hebdo murders, artists and writers faced intense repression from governments throughout the year. In Malaysia, cartoonist Zunar is facing a possible 43-year prison sentence for alleged ‘sedition’; in Iran, cartoonist Atena Fardaghani is serving a 12-year sentence for a political cartoon; and in Saudi Arabia, Palestinian poet Ashraf Fayadh was sentenced to death for the views he expressed in his poetry.

Perhaps the most far-reaching threats to freedom of expression in 2015 came from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries including France, Britain and Germany issued a statement in which they called on Internet service providers to identify and remove online content ‘that aims to incite hatred and terror.’ In July, the French Senate passed a controversial law giving sweeping new powers to the intelligence agencies to spy on citizens, which the UN Human Rights Committee categorised as “excessively broad”.

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the State. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On the anniversary of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, we, the undersigned, call on all Governments to:

- Uphold their international obligations to protect the rights of freedom of expression and information for all, and especially for journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders to publish, write and speak freely;

- Promote a safe and enabling environment for those who exercise their right to freedom of expression, and ensure that journalists, artists and human rights defenders may perform their work without interference;

- Combat impunity for threats and violations aimed at journalists and others exercising their right to freedom of expression, and ensure impartial, timely and thorough investigations that bring the executors and masterminds behind such crimes to justice. Also ensure victims and their families have expedient access to appropriate remedies;

- Repeal legislation which restricts the right to legitimate freedom of expression, especially vague and overbroad national security, sedition, obscenity, blasphemy and criminal defamation laws, and other legislation used to imprison, harass and silence critical voices, including on social media and online;

- Ensure that respect for human rights is at the heart of communication surveillance policy. Laws and legal standards governing communication surveillance must therefore be updated, strengthened and brought under legislative and judicial control. Any interference can only be justified if it is clearly defined by law, pursues a legitimate aim and is strictly necessary to the aim pursued.

PEN International

ActiveWatch – Media Monitoring Agency

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian Association of Journalists

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Bytes for All

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Independent Journalism – Romania

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Comité por la Libre Expresión – C-Libre

Committee to Protect Journalists

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Foundation for Press Freedom – FLIP

Freedom Forum

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression – Turkey

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

Instituto de Prensa y Libertad de Expresión – IPLEX

Instituto Prensa y Sociedad de Venezuela

International Federation of Journalists

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Journaliste en danger

Maharat Foundation

MARCH

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Foundation for West Africa

National Union of Somali Journalists

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

Reporters Without Borders

South East European Network for Professionalization of Media

Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters – AMARC

PEN Mali

PEN Kenya

PEN Nigeria

PEN South Africa

PEN Eritrea in Exile

PEN Zambia

PEN Afrikaans

PEN Ethiopia

PEN Lebanon

Palestinian PEN

Turkish PEN

PEN Quebec

PEN Colombia

PEN Peru

PEN Bolivia

PEN San Miguel

PEN USA

English PEN

Icelandic PEN

PEN Norway

Portuguese PEN

PEN Bosnia

PEN Croatia

Danish PEN

PEN Netherlands

German PEN

Finnish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

Slovenian PEN

PEN Suisse Romand

Flanders PEN

PEN Trieste

Russian PEN

PEN Japan

16 Dec 2015 | Awards, Events, mobile, Press Releases

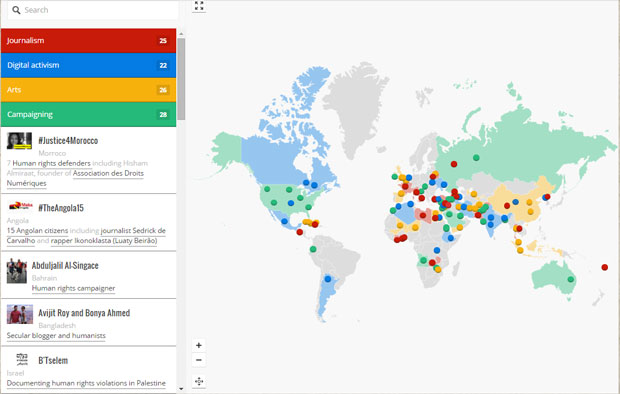

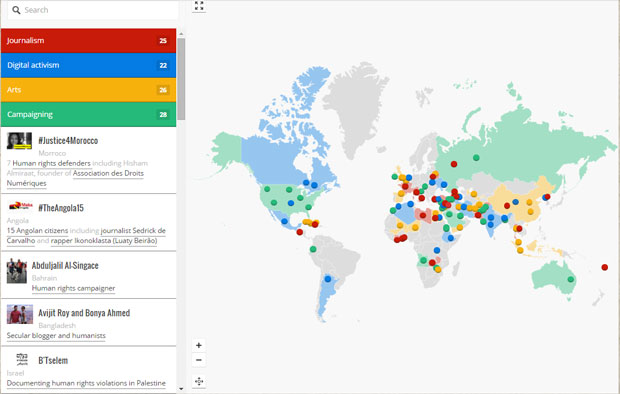

A graffiti artist who paints murals in war-torn Yemen, a jailed Bahraini academic and the Ethiopia’s Zone 9 bloggers are among those honoured in this year’s #Index100 list of global free expression heroes.

Selected from public nominations from around the world, the #Index100 highlights champions against censorship and those who fight for free expression against the odds in the fields of arts, journalism, activism and technology and whose work had a marked impact in 2015.

Those on the long list include Chinese human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang, Angolan journalist Sedrick de Carvalho, website Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently and refugee arts venue Good Chance Calais. The #Index100 includes nominees from 53 countries ranging from Azerbaijan to China to El Salvador and Zambia, and who were selected from around 500 public nominations.

“The individuals and organisations listed in the #Index100 demonstrate courage, creativity and determination in tackling threats to censorship in every corner of globe. They are a testament to the universal value of free expression. Without their efforts in the face of huge obstacles, often under violent harassment, the world would be a darker place,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

Those in the #Index100 form the long list for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards to be presented in April. Now in their 16th year, the awards recognise artists, journalists and campaigners who have had a marked impact in tackling censorship, or in defending free expression, in the past year. Previous winners include Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, Argentina-born conductor Daniel Barenboim and Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat.

A shortlist will be announced in January 2016 and winners then selected by an international panel of judges. This year’s judges include Nobel Prize winning author Wole Soyinka, classical pianist James Rhodes and award-winning journalist María Teresa Ronderos. Other judges include Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab, tech “queen of startups” Bindi Karia and human rights lawyer Kirsty Brimelow QC.

The winners will be announced on 13 April at a gala ceremony at London’s Unicorn Theatre.

The awards are distinctive in attempting to identify individuals whose work might be little acknowledged outside their own communities. Judges place particular emphasis on the impact that the awards and the Index fellowship can have on winners in enhancing their security, magnifying the impact of their work or increasing their sustainability. Winners become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given support for the year after their fellowship on one aspect of their work.

“The award ceremony was aired by all community radios in northern Kenya and reached many people. I am happy because it will give women courage to stand up for their rights,” said 2015’s winner of the Index campaigning award, Amran Abdundi, a women’s rights activist working on the treacherous border between Somalia and Kenya.

Each member of the long list is shown on an interactive map on the Index website where people can find out more about their work. This is the first time Index has published the long list for the awards.

For more information on the #Index100, please contact [email protected] or call 0207 260 2665.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]