2 Sep 2022 | Opinion, Russia, Ruth's blog

Mikhail Gorbachev in 2008. The former president of the Soviet Union passed away on 30 August. Credit: European Parliament

In every field there are people who become living legends, people who inspire their colleagues and shape their chosen field. They add to our collective knowledge, they shape the world we live in and their contributions ensure that we both question the status-quo and think again about our individual and collective core values.

Sometimes these people reach further than their own fields. Sometimes they inspire or challenge the world. Whether as thinkers, writers or leaders. Sometimes their experiences and their contributions come to define an era of history – for some maybe even just one year.

1989. A year of deep turmoil. A year that reshaped the world. A year that defined the next generation. A year of both hope and horror. And on a personal level, a year that defined the type of world that I was going to live in.

1989 saw the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Tiananmen Square protests, the Velvet Revolution, the Hillsborough disaster, the Exxon Valdez spill, Solidarity was elected in Poland, FW de Klerk was elected in South Africa, Sky TV was launched and the Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Salman Rushdie. In different ways each of these events shaped the world we live in today – 33 years later.

I often write that there has been too much news. Too many issues for the Index team to cover. Too many crises. In 1989 we published nine editions of the magazine, to keep up with the news and to ensure that voices of dissidents were being heard, as authoritarian regimes began to fall.

In the last month I have found myself thinking a great deal about the events of 1989 and what they led to. The path of history that was chosen on those pivotal days and the actions of our leaders whose immediate responses to these events had long-term consequences. Whilst there are many global figures who dominated the news during my childhood, two of them have this month caused me to pause and consider what the world would have been like if they hadn’t been brave enough to challenge the status quo.

Sir Salman Rushdie and Mikhail Gorbachev.

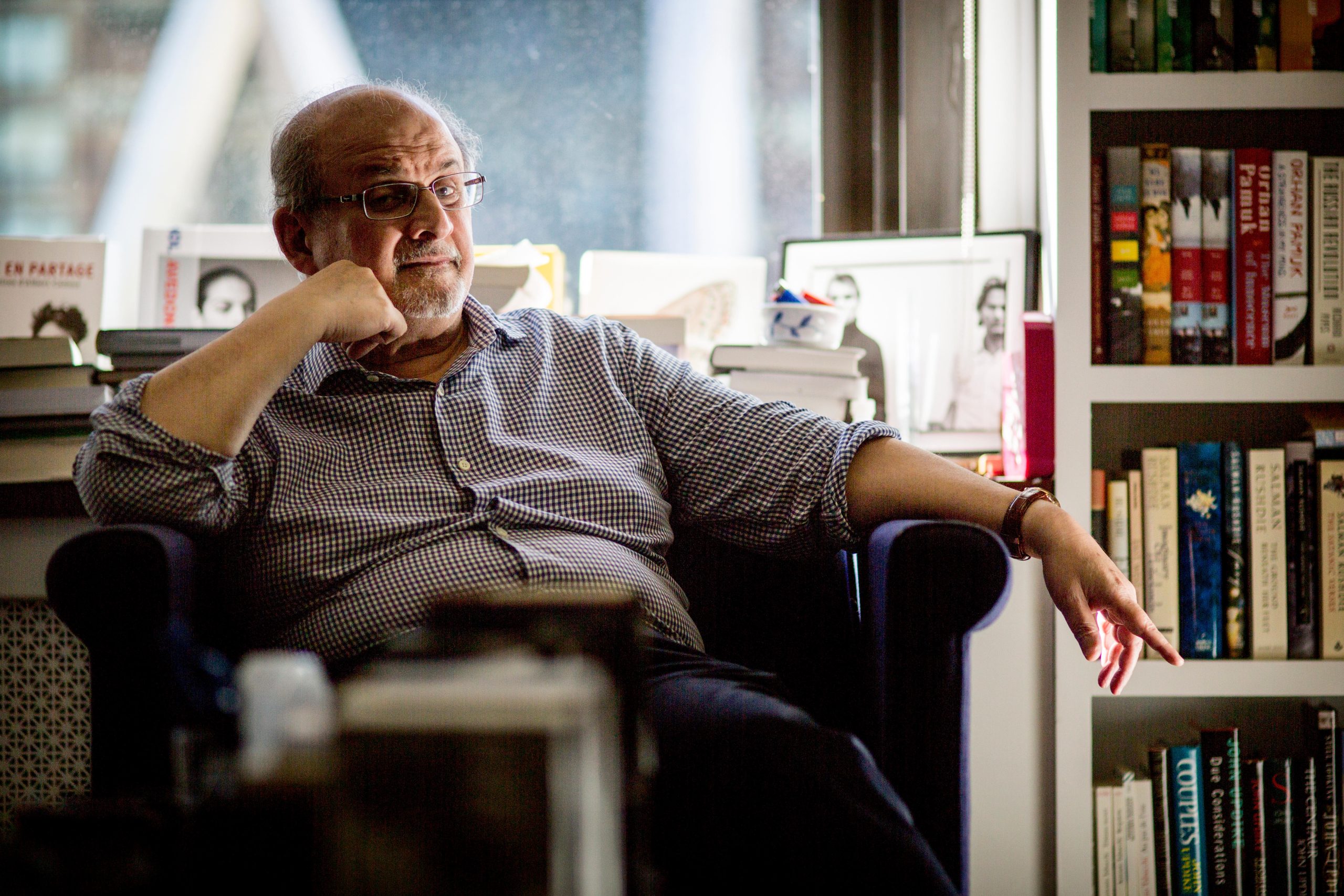

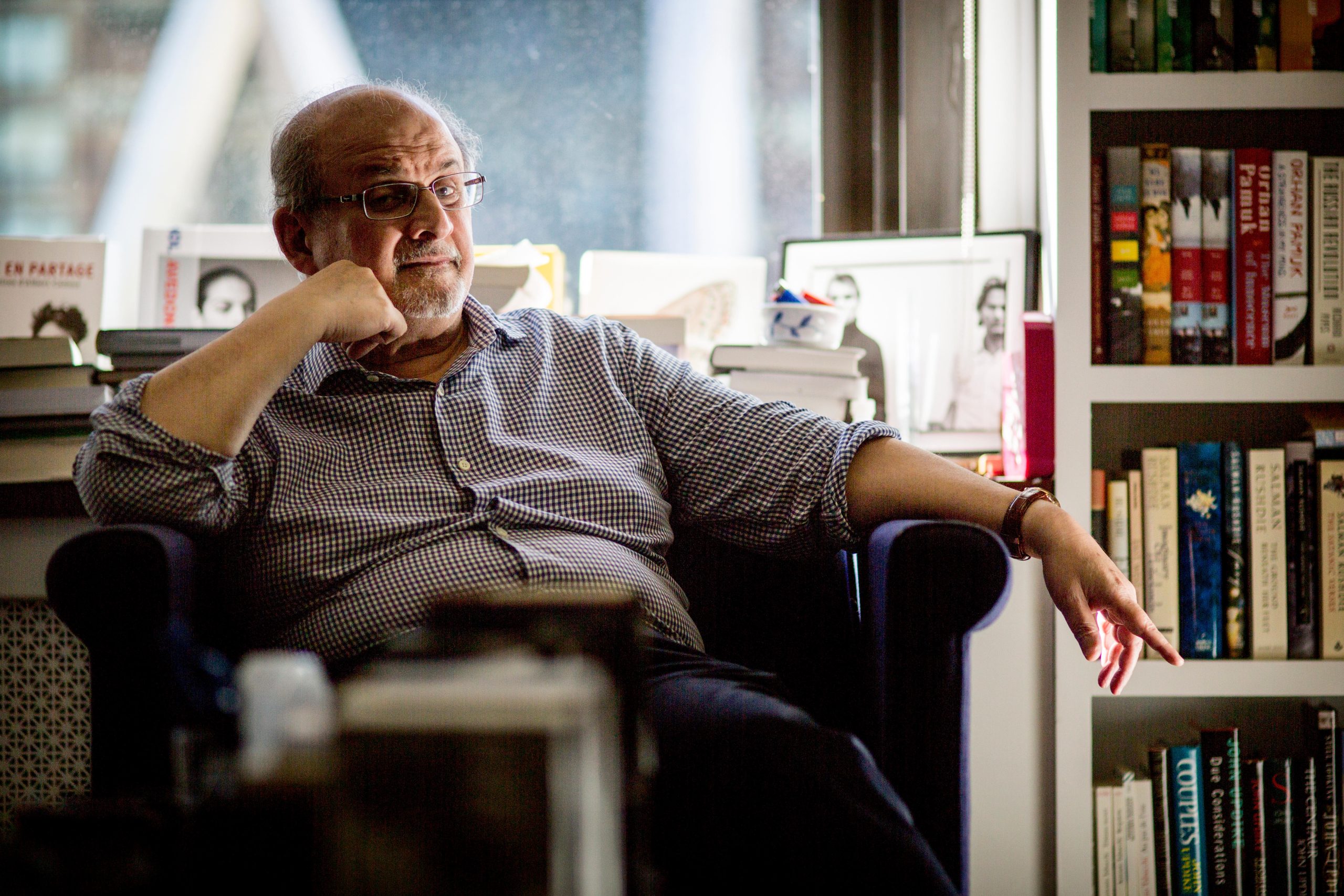

Salman Rushdie pictured in New York in 2016. Credit: Orjan Ellingvag/Alamy

Every day since the horrendous attack on Sir Salman, last month, Index has received messages of support for him as he recovers from his injuries. The messages have been touching, political and occasionally controversial – just like his writings! What they have demonstrated is regardless of people’s associations with him and their feelings towards him, his bravery and commitment to the values of freedom of expression in the face of the gravest of threats inspired a generation.

For over three decades he has refused to be intimidated, to be cowed. He continued to write, to speak and stay true to his values. He embodies the fight of the dissident, the determination to be heard and the power of words. He has shaped my approach to the world we live in and more importantly he has provided a role model for all of those that Index seeks to support and promote every day. I am so pleased that those who sought to assassinate him failed and we still have him amongst us.

In a different way Mikhail Gorbachev is just as fundamental to the history of Index. I’m not sure that Michael Scammell, the first editor of Index, would have believed that within a decade of Gorbachev’s coming to power in the USSR his writing would be in Index. His bravery in embracing glasnost provided hope for a generation.

The fall of the Berlin Wall without military repercussions provided hope of a peaceful transition to democracy – not just in central and eastern Europe but throughout the world.

This isn’t to say he wasn’t flawed. He was and his actions in the Baltics and the Caucuses were as expected from an authoritarian leader, and his support for the 2014 annexation of Crimea will forever tarnish his legacy.

But… Index was founded to provide a platform for samizdat, to provide a voice for dissidents who lived behind the Iron Curtain, to campaign for the right to freedom of expression both in the USSR and around the world. His bravery in embracing glasnost provided space for people to speak freely, to write and to be heard, even if Putin once again has shut the door. Gorbachev enabled people to get a taste of what they were missing. We can only hope that in the long arch of history glasnost will win out.

5 Aug 2022 | Afghanistan, Belarus, Brazil, Indonesia, Kenya, News and features, Poland, Russia, South Africa, United Kingdom

Belarus Free Theatre’s Dogs of Europe in rehearsal. Photo: Mikalai Kuprych

Index on Censorship has always supported the theatre of resistance, and our Winter 2021 magazine even had this issue as its main theme.

In Belarus, for example, organisations such as Belarus Free Theatre are crucial to fighting Lukashenka’s ruthless regime. Playwrights in Turkey have also faced government censorship throughout history and have to find their way around it.

In the UK, theatre censorship was officially abolished in 1968, putting an end to over 200 years of control by the Lord Chamberlain. Countries like Brazil are also making things harder for the arts and theatre sector through a kind of financial censorship linked to ideological values.

Now, we explore the universe of theatre and censorship, looking back at pieces published in our magazine.

Staging dissent: When a British prime minister was not amused by satire, theatre censorship followed. We revisit plays that riled him, 50 years after the abolition of the state censor

In this piece published in 2018, actor and director Simon Callow revisited the struggle to officially abolish censorship in theatre in the UK, which happened in 1968, after lasting for almost 200 years.

He explains why vigilance is still needed nowadays and writes about other forms of censorship, such as self-censorship.

Theatre Censorship

In August 1980, Anna Tamarchenko wrote a piece about the strict and recurrent censorship in Russian theatre.

She exemplifies her point of view citing Russian plays that only hit the stage years after being written, such as Boris Godunov, first staged in 1870, 45 years after it was published. Alexander Pushkin, its author, had already passed away 30 years earlier.

“Under the Soviet regime censorship has gained new opportunities to exert pressure on theatrical life,” Tamarchenko wrote.

Alternative theatre

In this piece published in 1985, theatre critic Agnieszka Wójcik (pseudonym) dives deeply into the censorship and repression against student theatre in Poland, especially following the introduction of Martial Law in December 1981, when student theatre began to be considered a threat to public order.

“The repressions following December 13 therefore somehow ‘objectively’ defined the status of student theatre as suspect, if not downright illegal. After the banning of NZS (the independent student union) which had taken most student groups under its wing during the Solidarity period, they lost the foundations of their material existence,” Wójcik wrote for Index.

Why the Taliban wanted my brave mother dead…

For the 2021 Winter issue of Index magazine, Associate Editor Mark Frary reported on the play The Boy with Two Hearts, written by Afghan author Hamed Amiri and inspired by his memories of his mother’s campaigns for women’s rights and why they had to leave Afghanistan behind.

“When Hamed Amiri was 10 years old he watched his mother Fariba give a speech in his hometown of Herat, Afghanistan, speaking out for women’s rights and education and against the ruling Taliban. A day later, a mullah gave the order for Fariba’s execution and the family began a gruelling 18-month journey through Europe,” Frary writes.

Testament to the power of theatre as rebellion

In December 2021, critic, columnist and cultural historian Kate Maltby wrote about Belarus Free Theatre’s journey towards performing at the Barbican in London in 2022.

She talked to Nikolai Khalezin, playwright and journalist, and Natalia Koliada, theatre producer. Both founded Belarus Free Theatre in March 2005 and told Index about the rollercoaster they’ve been through after going into exile in order to escape from Lukashenka’s dictatorship.

“Since 2011, Khalezin and Koliada have held political asylum in the UK, a necessity for survival in the face of repeated harassment and imprisonment at the hands of Lukashenka’s regime”, writes Maltby.

Where silence is the greatest fear

Published in December 2021, this piece written by Issa Sikiti da Silva, Index contributing editor based in West Africa, looks at the censorship suffered by Kenyan theatre and how it has dragged under a series of corrupt leaders.

He also investigates the legacy left by colonial Britain in Kenya and how it still impacts theatre in the country.

“There was hope that Jomo Kenyatta’s ascension to the presidency in 1964 would help heal the wounds inflicted by the British and pave the way to tolerance, social justice, freedom and prosperity,” Da Silva writes.

God waits in the wings…ominously

Brazil is also home to its share of theatre censorship and free speech issues. In December 2021, Index’s editorial assistant Guilherme Osinski and former associate editor Mark Seacombe reported on a presidential decree that art must be sacred. They explored how it has affected Brazilian theatres across the country.

Osinski and Seacombe interviewed two Brazilian theatre companies, which shared their thoughts on president Jair Bolsonaro’s approach to art in Brazil, comparing the current situation to when the country faced a bloody dictatorship from 1964 to 1985.

“While the overt and ruthless censorship of the military dictatorship that ended in 1985 is now history, theatre today has to comply with a nebulous concept known as “sacred art” or be starved of public funds”, writes Osinski.

Desegregating the theatre

In August 1985, Professor Stephen Gray wrote for Index and explained how theatre in South Africa was shaped and controlled by the law, before this censorship was eventually relaxed and became less strict.

“Theatre itself is debate, and in South Africa, where sensitive issues ignite like flash-paper, to each show its own controversy,” Gray writes.

Play politics: policing theatre in Indonesia

At the beginning of the 1990s, Indonesia’s government had promised more openness and freedom for theatre companies in the country. However, president Suharto closed the doors on Jakarta’s popular theatre and other plays began to be banned across Indonesia.

Andrea Webster reported on that issue for Index in July 1991, emphasising the ironies between Suharto’s speech for democracy and the bans and curbs on theatres.

“The ban occurred just over a month after President Suharto himself made an Independence Day speech on 17 August where he spoke of ‘openness’ and democracy, where ‘differences of opinion had their place in Indonesian society,’” Webster wrote on the occasion.

Sending out a message in a bottle: Actor Neil Pearson, who shot to international fame as the sexist boss in the Bridget Jones films, talks about book banning and how the fight against theatre censorship still goes on

In June 2019, then editor in chief of Index on Censorship, Rachael Jolley, interviewed actor Neil Pearson about why governments fear books being published and how the fight against theatre censorship still goes on.

Among many things, they discussed self-censorship and the boundaries between a play which is acceptably controversial and unacceptably controversial.

“If you are genuinely against censorship, you have to be evenhanded against censorship. If your idea of freedom of speech is only allowing people to say what you already agree with, then Goebbels would have no problem with that definition of speech,” Pearson told Index.

‘Humpty Dumpty has maybe had the last word…’

One of the biggest names in British theatre recently wrote for Index on Censorship. Sir Tom Stoppard, playwright and screenwriter and whose work covers themes such as human rights, censorship and political freedom, wrote in December 2021 on how the battleship over freedom still lies between the individual and the state.