10 Mar 2017 | Denmark, Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Few people take religion less seriously than the Danes.

Few people take religion less seriously than the Danes.

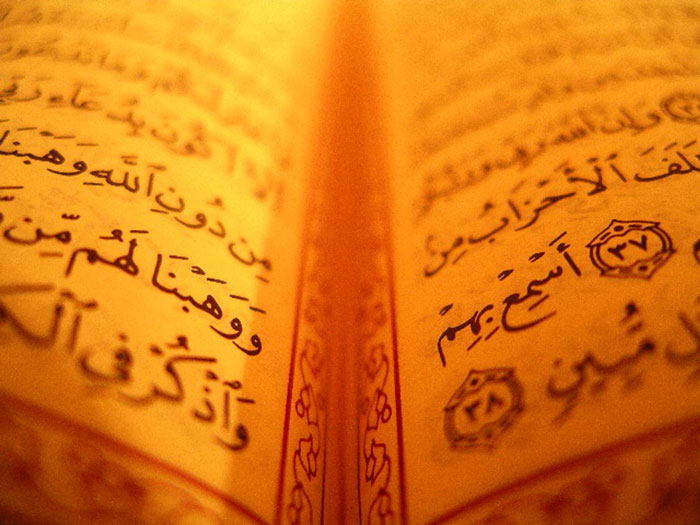

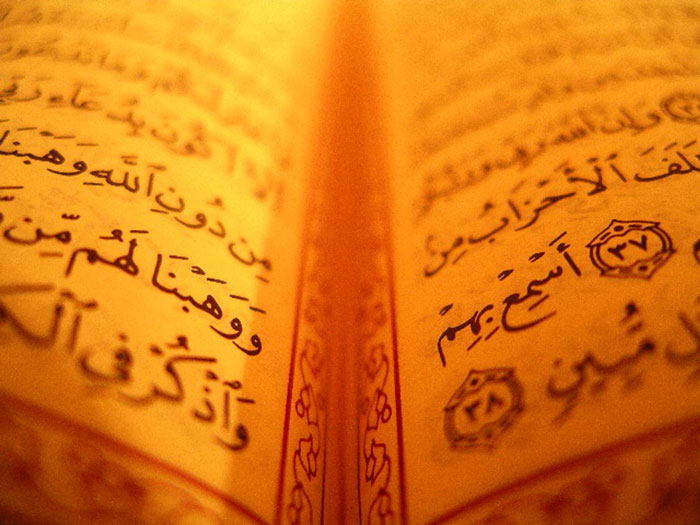

Only 19% consider religion to be an important factor in their day to day lives. While some 76% remain members of the state church, that figure is down from 83% in 2006, and more than 24,000 people left the institution last year. Church going remains popular at Christmas, weddings and baptisms, but many churches are almost empty on any given Sunday. Long gone are the days when criticising the doctrines of Lutheranism or the Lutheran state church would land you in prison (or on the scaffold). So it created quite a stir when in February a local prosecutor announced that a Danish man was being charged for violating Denmark’s blasphemy law, which has been dormant since 1971 and last resulted in a conviction in 1946. A move approved by Denmark’s chief prosecutor.

How was a dead letter such as the Danish blasphemy ban suddenly revived?

The first step was taken by the Danish Criminal Law Council, an expert body advising the Ministry of Justice. In 2015 it released a lengthy statement on the blasphemy ban arguing that the burning of holy books would still be punishable, despite the decades-long practice of emphasising the importance of free speech over religious feelings. However, suspiciously, the expert body omitted any reference to a case from 1997 in which a Danish artist burned the Bible on national television.

Back then a number of complaints from the public were dismissed by the chief prosecutor emphasising among other things the importance of freedom of expression. It is difficult to understand why this seemingly clear precedent was disregarded by the expert body. But it was this questionable interpretation that paved the way for bringing back from the dead a ban thought of as antiquated and incompatible with a secular liberal democracy by most Danes, and indeed by most Europeans, since only five EU-member states still have blasphemy bans on the books.

One of the reasons cited by the expert body for punishing the burning of holy books is the need to prevent religious extremists – at home and abroad – from instigating riots and violence as a result of having their religious feelings insulted. This is a deeply problematic argument in and of itself, but even more so in the context of Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten having been the target of at least four foiled terrorist attacks since publishing cartoons of the prophet Muhammad in 2005, the murderous attack on Charlie Hebdo in 2015 and the killings of atheists and free thinkers in Bangladesh. A blasphemy ban indirectly legitimizes the Jihadist’s Veto, rather than confronting it. It is not punishable – nor should it be – to burn the Danish flag as has happened repeatedly in protests against the cartoons both in Denmark and abroad. No one would dream of arguing that it should be a crime to burn the Communist manifesto, Burke’s Reflection on the French Revolution, or Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations even though communists, conservatives and classical liberals might view these works as essential to their identities and deeply held beliefs. In all likelihood one of the most frequently burned book of the 20th century was Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, which went up in flames all over the world as offended Muslims took to the streets. Offended Muslims were free to do so, while Rushdie had to spend years living underground.

While burning books is certainly a crude and primitive practice with deeply troublesome historical connotations, it is nonetheless a peaceful symbolic expression, that should be protected free speech, whether the content of the scorched paper is secular or religious. By solely protecting religious books against such desecration the Danish blasphemy ban not only violates free speech and equality before the law, it is also tantamount to victim blaming and a dereliction of duty on the part of a liberal society which in no uncertain terms should make clear to religious fundamentalists that they cannot hope to have democracies impose their religious red lines on the rest of society through threats, intimidation and violence.

This was a point made clear by both Norway and Iceland whose parliaments chose to abolish these countries’ respective blasphemy bans as a direct consequence of the attack against Charlie Hebdo.

It would be wrong however, to suggest that Denmark has succumbed to the will of Islamists in particular, rather than to a loss of faith in free speech in general. Last year Parliament adopted a bill prohibiting “religious teachings” that “expressly condone” certain punishable acts and allows the government to maintain a dynamic list of “hate preachers” barred from entering Denmark. These initiatives were the direct consequence of a documentary exposing radical imams in Danish mosques preaching that the punishment for adultery and apostasy is stoning. And the current government has also presented a bill that would criminalize the mere sharing of “terrorist propaganda” online and allow the police to block access to websites containing criminal material such as terrorist propaganda or racist content. These developments signal a marked shift in the Danish approach to free speech.

In the post-World War II era Denmark has with a few exceptions been a liberal democracy committed to the idea that freedom of expression was an essential tool in defeating extremism and totalitarian ideologies. But Denmark is turning towards a model of militant democracy where free speech is often seen as the problem rather than the solution, and as a hindrance rather than the foundation of social peace. The revival of the Danish blasphemy ban should therefore be seen in the wider context of a world where respect for freedom of expression is at its lowest level in 12 years, a development that has now affected even one of the global bastions and beacons of free speech.

Jacob Mchangama is director of Justicia, a Copenhagen think tank focusing on human rights and the rule of law[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1489139072253-6b7daeee-fe12-8″ taxonomies=”53″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Nov 2016 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Ladies and gentlemen, Rafto laureates. It is my pleasure to be asked to speak to you today on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Rafto Foundation.

I represent Index on Censorship, an organisation that was born, much like Rafto, to help give voice and support to dissidents behind the Iron Curtain but whose mission, like Rafto’s, quickly spread much wider. Index is a freedom of expression organisation that campaigns against censorship globally and promotes the value of free expression.

Today I will talk about what I think is the hardest of all issues for free speech activists: the question of hate speech. And the question of whether it is possible to balance a belief in true freedom of expression for all with the recognition that, in many instances, hateful speech is used in such a way that can suppress the voices of minority and oppress groups.

What I want to offer today is a provocation. I want to argue that it is only by allowing free speech – that is allowing all forms of speech, including those espousing hateful views – that we can ultimately protect minority and oppressed groups. That the answer to hateful speech is not more bans or ever widening laws or definitions of hate, but finding mechanisms that better allow the speech of all groups to flow.

If the market for free ideas and the free exchange of ideas and opinions does not yet work perfectly, the answer is not to ban people from having a voice

I want to start by going back to basics and asking the question, why is free speech important? For me, and for Index, freedom of speech is the most important freedom because it is the freedom on which all others rest. If one cannot express freely one’s desires, one’s political or religious views, how can we be truly free? Without free speech, how can one speak out against the oppressor. Without free speech, the oppressed and marginalised are forced to suffer in silence.

John Stuart Mill wrote: “It is on the freedom of opinion and the freedom of expression of opinion, that the well-being of mankind depends” but I think Shahzad Ahmad, the 2014 winner of Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards said it better: “Freedom of expression. To me this is the ultimate freedom: it means the freedom to live, to think, to love, to be loved, to be secure, to be happy.”

Freedom of speech is enshrined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, the First Amendment. It became a sort of mantra in the wake of the killings last year at French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. You would think this was a freedom and a value on which we could all agree. And yet. And yet. The question of where we draw the line on free speech drives a wedge through our apparent agreement that free speech is a universal good with parameters on which we can all agree. And it is this ‘I am in favour of free speech BUT’ question that I want to address today.

Most commonly articulated in the aftermath of Charlie Hebdo was the position “I am in favour of free speech” but not when it is targeted against minorities. Definitions of what constituted a minority in these instances differed – from the religious groupings to ethnic grouping to socio-economic groupings. This sense that speech should not be used to punch down found its most powerful manifestation in the objection to many members of the American PEN center to Charlie Hebdo receiving a courage award in the months after the killings. This led still more – including a number of governments – to suggest that in order to deal with the effects of offensive speech, what was needed were more hate speech laws, not fewer. Those who objected to the works of groups like Charlie Hebdo argued that this would help protect minorities from words and images that they believe leads directly to more aggressive forms of discrimination, but also protect communities from the burgeoning non-violent, but nevertheless extremist messaging that many nations see as the source of violent extremism.

In practice, this sounds fairly reasonable. Cut out the hateful words, eliminate the violent behaviours, the discrimination, the racism, the homophobia. Except this is not how it works. And those who advocate and wish for additional hate speech laws, which – increasingly – seem to mark the advent of a return to blasphemy laws in many places where we thought they had been eliminated – should be careful what they wish for.

As the US delegation noted in a Human Rights Council meeting last year: “legal prohibitions on incitement are often used to persecute members of minority groups and political opponents, raising serious freedom of expression concerns.

“Such laws, including blasphemy laws, tend to reinforce divisions rather than promote societal harmony. The presence of these laws has little discernable effect on reducing actual incidences of hate speech. In some cases such laws actually serve to foment violence against members of minority groups accused of expressing unpopular viewpoints.

“In addition, legal prohibitions can displace societal efforts to combat intolerance. This occurs because disputes over hate speech are then seen as matters for courts to decide rather than society at large. Combating hate speech requires a change in the societal attitudes that give rise to discriminatory views. Prohibiting speech is a poor, if not counterproductive, means of achieving that goal.”

You need look no further than the discussions within the same Human Rights Council for evidence of the way in which hate speech laws are easily manipulated to target those with opposing view rather than protect minorities. During the debate, Russia praised hate speech laws, talking of the need to monitor “hate speech“ in Ukraine so as not to ignite “nationalistic fires.”

China – not celebrated for its tolerance of free speech – praised hate speech legislation, saying speech on the internet needed to promote the “norms of civilisation” and “harmony.”

It is easy to feel, particularly in the wake of Brexit in the UK and the rise of the so-called alt-right in the US, and the apparent rise in hateful, racist and misogynistic speech, that the best solution to support those affected such speech is to ban it. But I want to argue strongly that any acts that actively seek to limit the speech of one group, is ultimately detrimental for all. I want to argue against the current meme I see particularly in American discourse that says free speech is a construct for privileged white men to argue that free speech – genuine free speech that includes the ability to say things others find offensive, hateful and hurtful – is what protects all our rights to speak. If the market for free ideas and the free exchange of ideas and opinions does not yet work perfectly, the answer is not to ban people from having a voice, it is to work even harder – as everyone of you here does on a daily basis – to raise up the voices of those who are still not being heard, to demand the right to speak.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1480340935409-d0a11d11-e407-8″ taxonomies=”6534″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Oct 2016 | Americas, mobile, News and features, United States

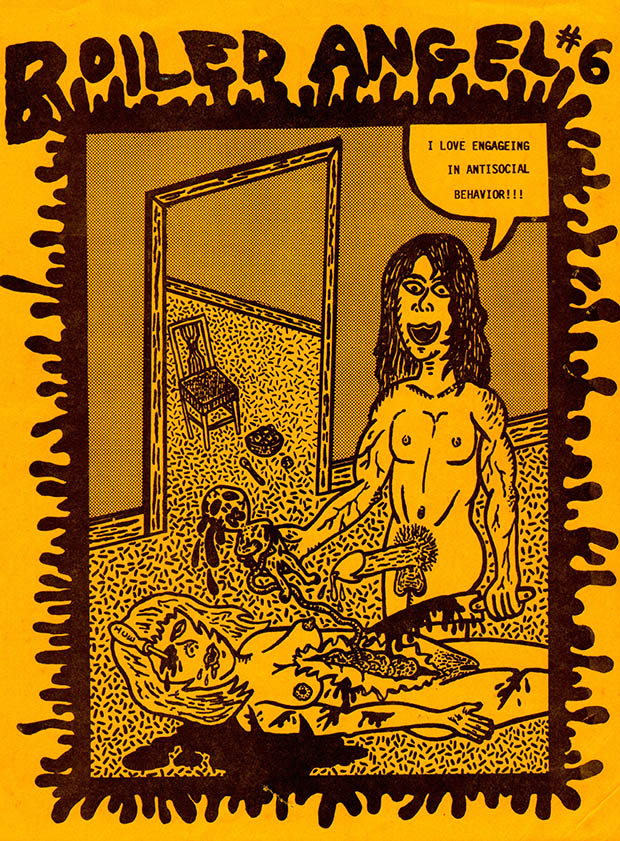

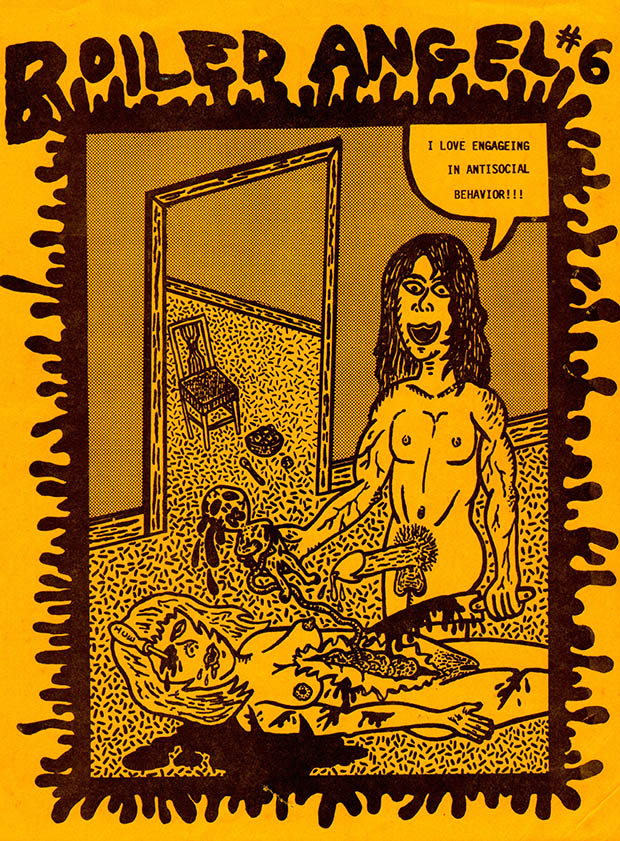

For the good of society, American cartoonist Mike Diana was jailed without bail in 1994. So ruled a jury at the Pinellas County court in Florida, taking just 90 minutes to find him guilty of obscenity following a week-long trial in March of that year.

Diana was the first – and to date, only – cartoonist to be jailed for his work in the USA.

His ordeal began when one of his Boiled Angel comics – with the stated aim of being “the most offensive zine ever made” – ended up in the hands of a law enforcement officer in California in 1991. The shocking (and often funny) depictions of sex and violence reminded him of a series of then-unsolved murders in Gainesville, Florida. He passed his suspicions on to counterparts in the Sunshine State who took a blood sample from Diana. The cartoonist was found to have had absolutely no links with the crime but prosecutor Stuart Baggish took one look at the comic “and knew right away what [he] was looking at was obscenity”.

Boiled sold only 300 copies by mail and the only issue sold in Dian’s hometown was to an undercover police officer. Although quickly released, Diana was given three years probation, ordered to pat a $3,000 fine, given 1,248 hours community service and ordered to avoid contact with minors.

A new documentary is in the works about Diana and the limitations of the right to free speech in the face of outrage and cries of obscenity. The Trial of Mike Diana, created by cult filmmaker Frank Henenlotter, has launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds to finish the film and to cover the costs of a legal review typical of a project which deals heavily with the American court system.

The documentary features many of those who were there during the 1994 trial, including Baggish, as well as interviews with Diana fans and supporters Neil Gaiman, Peter Bagge and Stephen Bissette.

Diana will contribute original animation to the film.

For a medium that lends itself so well to the light-hearted, cartoons have frequently fallen victim to censors. More than two decades on from the sentencing of Diana, they still face prosecution, persecution, death threats and abuse worldwide. Last year’s attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo was the most high-profile example of just how dangerous the medium can be.

Could history be repeated in the USA? Are the freedoms many Americans take for granted at risk? As Henenlotter puts it: “Freedom of Speech doesn’t mean anything if your art is declared ‘obscene’ and one man’s art could be another man’s obscenity. That’s the battle we explore in this documentary: an improbable collision between comic-book art and the First Amendment.”

More articles about cartoonists:

Targeted cartoonists show support for Charlie Hebdo

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar says “I will keep drawing until the last drop of my ink”

Ecuadorean cartoonist Bonil facing charges after mocking politician

Indian cartoonist arrested on sedition charges

16 Sep 2016 | Bosnia, Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Italy, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Netherlands, News and features, Serbia

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Members of the Greek far-right Golden Dawn party assaulted a journalist at a protest against the presence of a refugee detention centre on the island of Chios on 14 September.

Editor-in-chief of Astrapari.gr, Ioannis Stevis, was covering the events at the entrance of the camp when a local representative of Golden Dawn, Mattheos Mermigousis, assaulted him and threw his camera on the ground where it broke.

Greek riot police were close by when the assault happened but refused to arrest Mermigkousi despite his request. Stevis has pressed charges against local Golden Dawn representatives.

Ismar Imamovic, an editor at local broadcaster RTV Visoko, was assaulted by a masked individual after he left the TV station on 14 September.

The incident occurred shortly after midnight. As Imamovic told Patria, a few seconds after he had left the building a masked man attacked him from behind. “First he struck me down and then beat me brutally,” Imamovic said.

The incident was reported to the police but so far there is no information regarding the culprits’ identity. Political parties have condemned the attack.

A Dutch-Turkish journalist for the Turkish pro-government newspaper Sabah was arrested in the city of Zaandam while reporting on a police operation on 12 September.

Fatih Ozyar was filming a police raid in an area of Zaandam when he was asked by the police to leave. He told the police that he was a journalist but was arrested with eight other people.

“I was treated roughly by four police officers and brought to a police cell where I was left for 15 hours,” he said. Ozyar was released the following day with a fine for not following police instructions.

The municipality of Amatrice announced on 12 September it plans to sue Charlie Hebdo magazine for a cartoon published about the 24 August earthquake that killed 295 people, Le Figaro reported.

The Amatrice municipal officials announced they were suing for libel.

“This is an unbelievable and senseless macabre insult made to victims of a natural disaster,” the municipality’s lawyer said.

Nedim Sejdinovic, the president of the Independent Journalist Association of Vojvodina, received death threats and threats of violence via Facebook on 12 September.

The threats came after Sejdinovic participated in a roundtable discussion about challenges in modern day Serbia. He compared Serbia in the 90s with the IS today. He also said that he believed Serbia’s ruling party was deeply corrupt and had destroyed society.

The Independent Association of Journalists in Serbia condemned the threats and urged a special prosecutor for cyber crime to identify those who are responsible.

Few people take religion less seriously than the Danes.

Few people take religion less seriously than the Danes.