15 Oct 2014 | Press Releases, Uncategorized

- Awards honour journalists, campaigners and artists fighting censorship globally

- Judges include journalist Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Sir Keir Starmer

- Nominate at www.indexoncensorship.org/nominations

Beginning today, nominations for the annual Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 2015 are open. Now in their 15th year, the awards have honoured some of the world’s most remarkable free expression heroes – from Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim to Syrian cartoonist Ali Farzat to education activist Malala Yousafzai.

The awards shine a spotlight on individuals fighting to speak out in the most dangerous and difficult of conditions. As Idrak Abbasov, 2012 award winner, said: “In Azerbaijan, telling the truth can cost a journalist their life… For the sake of this right we accept that our lives are in danger, as are the lives of our families. But the goal is worth it, since the right to truth is worth more than a life without truth.” Pakistani internet rights campaigner Shahzad Ahmad, a 2014 award winner, said the awards “illustrate to our government and our fellow citizens that the world is watching”.

Index invites the public, NGOs, and media organisations to nominate anyone they believe deserves to be part of this impressive peer group: a hall of fame of those who are at the forefront of tackling censorship. There are four categories of award: Campaigner (sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers); Digital Activism (sponsored by Google); Journalism (sponsored by The Guardian), and the Arts. Nominations can be made online via http://www.indexoncensorship.org/nominations

Winners will be flown to London for the ceremony, which takes place at The Barbican on March 18 2015. In addition, to mark the 15th anniversary of the Freedom of Expression awards, Index is inaugurating an Awards Fellowship to extend the benefits of the award. The fellowship will be open to all winners and will offer training and support to amplify their work for free expression. Fellows will become part of a world-class network of campaigners, activists and artists sharing best practice on tackling censorship threats internationally.

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index, said: “The Index Freedom of Expression Awards is a chance for those whom others try to silence to have their voices heard. I encourage everyone, no matter where they are in the world, to nominate a free expression hero.”

The 2015 awards shortlist will be announced on January 27th 2015. Judges include journalist Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Sir Keir Starmer. The public will be asked to participate in selecting the winner of the Google Digital Activism award through a public vote beginning January 27th 2015. Sir Keir said: “Freedom of expression is part of the bedrock of civilised, democratic society. The Index on Censorship Awards have a material influence on promoting such freedom and both celebrating and protecting those who fight against censorship worldwide. That’s why Doughty Street Chambers chooses Index as its principal charity.”

For more information please contact David Heinemann: [email protected]

_______________________________________________________________________

NOTES FOR EDITORS

About Index on Censorship:

Index on Censorship is an international organisation that promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression. The inspiration of poet Stephen Spender, Index was founded in 1972 to publish the untold stories of dissidents behind the Iron Curtain and beyond. Today, we fight for free speech around the world, challenging censorship whenever and wherever it occurs. Index believes that free expression is the foundation of a free society and endorses Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.”

About The Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards:

The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise those deemed to be making the greatest impact in tackling censorship in their chosen area.

Awards categories:

Journalism – for impactful, original, unwavering journalism across all media (sponsored by The Guardian).

Campaigner – for campaigners and activists who have fought censorship and who challenge political repression (sponsored by Doughty St Chambers).

Digital Activism – for innovative uses of new technology to circumvent censorship and foster debate (sponsored by Google).

Arts – for artists and producers whose work asserts artistic freedom and battles repression and injustice.

Previous award winners include:

Journalism: Azadliq (Azerbaijan), Kostas Vaxevanis (Greece), Idrak Abbasov (Azerbaijan), Ibrahim Eissa (Egypt), Radio La Voz (Peru), Sunday Leader (Sri Lanka), Arat Dink (Turkey), Kareen Amer (Egypt), Sihem Bensedrine (Tunisia), Sumi Khan (Bangladesh), Fergal Keane (Ireland), Anna Politkovskaya (Russia), Mashallah Shamsolvaezin (Iran)

Digital/New Media: Bassel Khartabil (Palestine/Syria), Freedom Fone (Zimbabwe), Nawaat (Tunisia), Twitter (USA), Psiphon (Canada), Centre4ConstitutionalRights (US), Wikileaks

Advocacy: Malala Yousafzai (Pakistan), Nabeel Rajab (Bahrain), Gao Zhisheng (China), Heather Brooke (UK), Malik Imtiaz Sarwar (Malaysia), U.Gambira (Burma), Siphiwe Hlope (Swaziland), Beatrice Mtetwa (Zimbabwe), Hashem Aghajari (Iran)

Arts: Zanele Muholi (South Africa), Ali Farzat (Syria), MF Husain (India), Yael Lerer/Andalus Publishing House (Israel), Sanar Yurdatapan (Turkey)

You have received this email because email address ‘[email protected]’ is subscribed to ‘AWARDS 2015 Call For Nominations’.

9 Oct 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

It’s the newsagents I’ll miss the most. There are few more reassuring signs of civilisation than a well-stocked newsagent.

The tiny shop next to my local London underground station lays out a trestle table every morning, upon which sits a vast range of papers; the UK nationals, of course, and the local north London papers. And then Irish local and regional papers. The Kerryman, the Anglo-Celt, the Roscommon Herald, the Kilkenny People, the Kildare Nationalist, like Patrick Kavanagh’s barge “bringing from Athy/ And other far-flung towns mythologies.”

Newspapers are enthralling, odd things. The idea that every day a short novel’s worth of text is somehow corralled into print is strange and brilliant. And yet, gather more than two print journalists, even from still-profitable publications, in a room, and talk will soon turn to managed decline of the newspaper industry in Europe and the United States, and how the industry must be more like Buzzfeed, or less like Buzzfeed (it is mandatory to have an opinion on Buzzfeed).

This week, a group journalists gathered in the House of St Barnabas in London’s Soho, to discuss whether or not Britain gets the press it “deserves”. The panel, chaired by Miranda Sawyer of the Bug Consultancy, featured journalists Sophie Heawood and Matt Kelly, and media analyst Douglas McCabe. Heawood, who recently took up the dream gig of The Guardian newspaper’s weekend magazine main column, spoke interestingly about her path into broadsheet journalism via music writing (proving the truth in the advice given to all aspiring writers, Heawood spotted the gap in The Guardian’s coverage of the London grime music scene and inserted herself in it). Heawood, who gave up a column with Vice for her current Guardian slot, pointed out the irony that while we all seem to be grieving for newspapers, she still saw it as a move up in the world to go from new media to old.

McCabe pointed out that while we grieve, lots of people are still going out every day to buy a newspaper. Eventually they may not, but this decline may not happen as soon as we think.

The venue, a candlelit chapel, lent the night a funereal air. Certainly the short speech given by former Daily Mirror features editor Kelly felt a little like a eulogy. Kelly talked about his time as an indentured apprentice on a small Merseyside paper 25 years ago, earning £4,000 a year, of learning the ropes of court reporting, local government, all the dull but necessary things vital to local journalism. He moved to the Liverpool Echo and then the Daily Mirror, where he started on a salary of £42,000 in 1996 (a number that drew gasps from the young audience, which, one suspected, contained quite a few people who were in the apparently common position of being “full-time journalists” who don’t really get paid).

The Scouse journalist recalled glorious times of fully-staffed newsroom where “the budget” was only something politicians needed to manage. He claimed to have had no idea how much money he spent on journalism over the years, but he had spent thousands on keeping undercover reporter Ryan Parry in Buckingham Palace for two months in 2003, a story which sticks in the brain mainly because it’s when we first found out that the Queen keeps her cornflakes in Tupperware. The story was a success: Daily Mirror circulation spiked by 25% for three days after initial publication.

This, Kelly suggested, does not happen anymore: once your story goes out on the web, it’s everywhere. That bounce is lost. But that was not the real concern, he suggested: the real concern was that the route through journalism he took was dead as a model, that young reporters were not learning the basics, and that the metric-measuring web would always lead people to favour clickbait over difficult stories. So do we get the press we deserve? No, suggested Kelly. We get a significantly better press than we deserve. Analytics appeared to show that people only really wanted to read titillation, and for years journalists and editors had kidded themselves that people admired them for their hard-hitting journalism.

This led Kelly to his conclusion: the public doesn’t even deserve the British press. Hacks work hard on genuine stories, and the public doesn’t read them.

It’s a humbling, sobering thought for a trade not known for humility or sobriety. All that work and there you are, utterly unappreciated. Ask the average person not engaged in the media to name a great scoop. They will say Watergate. Ask them for another, and they might say MPs expenses. Ask what papers, or even what journalists were responsible for them, and the people who have seen All The President’s Men might be able to answer.

For most people, journalism and the media are kind of nebulous background noise. In the past, you had some kind of reason why you bought a particular newspaper, even if that reason was just that you always bought that newspaper. Increasingly though, people are barely aware of what publication they’re reading. Ask a recent graduate what site they read every day, or what their preferred news source is, and they will say be more likely to say Twitter than The Guardian. Which is why that publication and others are scrabbling to find new ways to bond with people beyond encouraging the reader going to a shop and buying a newspaper.

This fragmentation brings up the question of whether newspapers will maintain their influential position in society (be that good or bad) and if not, whether this will affect arguments for press freedom as distinguishable from everyday rights and liberties. We witness versions of this question from time to time: when local bloggers are excluded from council meetings because they are not accredited press, even if they are the only people in the area willing and able to cover the proceedings, for example. In the past, papers have been defensive of their position (many journalists can still get a scarcely believable amount of contempt into the word “blogger”) but in the post-Leveson world, in Life After Brian, it’s apparent that there is an interest in ensuring that press freedom and free speech are universal.

Explore the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine for discussion on the Seeing the future of journalism: Will the public know more? In print, online or on your iPad.

This article was posted on 9 October 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Sep 2014 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Politics and Society

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

“States must stop trying to define who is and isn’t a journalist. The media landscape has changed irreversibly,” said Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, as she opened the organisation’s Open Journalism event in Vienna on Friday, 19 Sept.

Journalism – wherever you draw its boundaries – has more voices than ever, but are all they all being properly recognised and safeguarded? This was one of the main problems addressed by the expert panel, which included Index on Censorship, alongside delegates from Azerbaijan, Serbia, Estonia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Bosnia and many other OSCE member states.

Gill Phillips, the Guardian’s director of editorial legal services, spoke via pre-recorded video about difficulties in defining journalism and deciding who gets journalistic protection. She cited the Snowden scoop, which was led by Glenn Greenwald, a former lawyer, and later embroiled his partner, David Miranda. Who gets the protection? Greenwald? Miranda? Lead staff reporter David Leigh? All three?

There was widespread condemnation of Russia’s new law, which compels bloggers with more than 3,000 views per day to be registered with the authorities. “[The bloggers] have certain privileges and obligations,” said Irina Levova, from the Russian Association of Electronic Communications, who repeatedly defended the law. “Online and offline rights are not the same,” she said, adding that some of those who deemed the law a mode of censorship have been revealed as “foreign agents”.

Another topic – raised repeatedly by various attendees – was Russian media’s growing influence over citizens in nearby countries. Begaim Usenova of the Media Policy Institute in Kyrgyzstan said: “The common view being spread from the Russian media is that the United States is starting world war three and only Putin can stop him.”

Yaman Akdeniz, a Turkish cyber-rights activist, shared news of Twitter accounts that remain blocked in his country, including some with over 500,000 followers. Igor Loskutov, a business director from Kazakhstan, looked back on the first 20 years of internet in his country and how authorities have gone from ignoring their first rudimentary websites to now wanting complete control.

The thorny issue of “public interest” was also discussed. Jose Alberto Azeredo Lopes, professor of International Law at the Catholic University of Porto, raised some smiles with his theory: “It’s like pornography. You can’t define it. But you know it when you see it.”

As the day-long discussions wrapped up, one delegate asked: if a blogger’s first-ever post goes viral, are they immediately subject to the same laws as the press? Especially in countries that now insist bloggers register.

The debate over the difference between journalists and bloggers went round in circles – as it always does – but the OSCE is hoping to be able to compile all the findings from its expert meetings into an online resource to move the discussion forward.

Azeredo Lopes concluded: “If you don’t distinguish freedom of expression from freedom of the press, you end up with no journalists, and that is the crisis that journalism faces today.”

Read our interview with Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE’s Representative on Freedom of the Media, in the autumn issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, coming soon

This article was published on Friday September 26 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Monday was the beginning of Banned Books Week, the annual celebration of the freedom to read and have access to information. Since the launch of Banned Books Week in 1982, over 11,300 books have been challenged, according to the American Library Association. To mark the occasion, Index on Censorship staff posed with their favourite banned books, and tell why it’s important that they are freely accessible.

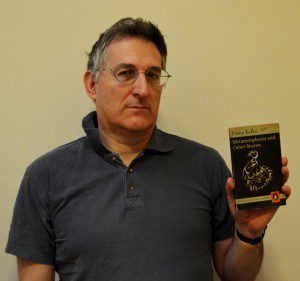

David Sewell (Photo by Dave Coscia)

David Sewell – Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

“Banned by the Soviet Union for being decadent and despairing and although they’re right in their analysis, the action to ban the book clearly is ludicrous. It’s a Freudian tale of Gregor Samsa who awakes one morning to find he has turned into a human sized bug and how his family react to this turn of events and treat him with revulsion and yes despair, since their main breadwinner is now out of commission. For a book about an insect grubbing about in filth, Kafka’s writing evinces some great beauty as did all his work despite the seam of despair underpinning many of them. Maybe this beauty through despair is what the Soviets meant by ‘decadent’. Kafka was a vital link between the end of the Victorian novel and the literary modernists and the influence of Freud’s ideas increasingly being used in characterisation. That is why ‘Metamorphosis’ is a significant book in the literary canon.”

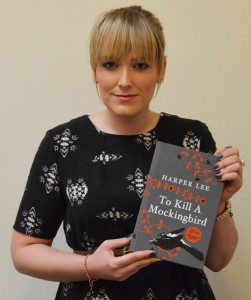

Aimée Hamilton (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Aimée Hamilton – To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

“Because of its use of profanities, racial slurs and graphically described scenes surrounding sensitive issues like rape, Harper Lee’s award winning novel has been banned in many libraries and schools in the United States over its 54 year history. Having read this beautifully written book at school, I think it should be a freely accessible curriculum staple, to be both enjoyed and admired by all.”

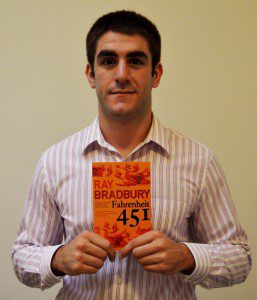

Dave Coscia (Photo by Aimée Hamilton)

David Coscia – Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

“Failing to or not choosing to see the irony, many schools in the United States banned Fahrenheit 451 based on its offensive language and graphic content. Bradbury’s grim view of a future where firemen are not people who put out fires, but instead set them in an attempt to burn books outlawed by the government, acts as a warning against state sponsored censorship, even if it’s not what he intended. Bradbury himself talks about Fahrenheit as a warning that technology would replace literature and cause humanity to become a “quick reading people.” What resonates with me about the novel is how prophetic that turned out to be. In the age of social media and instant information, humans, myself included, have gotten lazy and spend less time enjoying literature.”

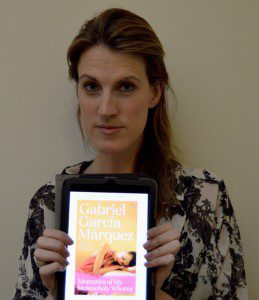

Vicky Baker (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Vicky Baker – Memories of My Melancholy Whores by Gabriel García Márquez:

“I picked this after reading how it was banned in Iran in 2007. Initially, it slipped through the censors’ net, as the Persian title had been changed to Memories of My Melancholy Sweethearts. It was on its way to becoming a bestseller before the ‘mistake’ was realised and it was whipped from shelves, accused of promoting prostitution. It’s classic tale of censors judging a book by its title.”

Sean Gallagher (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Sean Gallagher – American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

“No book, no matter how vilified or disliked, should be out of reach for anyone who wants to read it.”

Jodie Ginsberg (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Jodie Ginsberg – Forever by Judy Blume

“I was one of the first girls in my class to own Judy Blume’s Forever and it was passed clandestinely from classmate to classmate until it finally fell apart, dog-eared (and highlighted in certain places…). It is a book that is powerfully linked in my mind – as for so many young kids – to the transition from childhood into the tricky years of teenage life. Reading it felt shocking, even dangerous. But also liberating.”

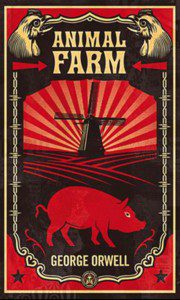

David Heinemann’s choice – Animal Farm

David Heinemann – Animal Farm by George Orwell

“It seems to have upset people from all ends of the political spectrum in one way or another at different times but what I love is that the story is actually quite ambiguous if you read it carefully, tearing pieces out of everyone and all angles. For its extraordinary imaginative power, the sheer audacity of its metaphors and it’s sharp alertness to the truths of life I treasure this book, having read it and been reminded of it so many times. I even adapted and staged the thing once, banning it is like depriving life of liquor.”

Fiona Bradley (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Fiona Bradley – Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

“I have chosen Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov because I think it is so deeply disturbing that it deserves to be read. It manages to convey some of the darkest human desires and emotions and these are exactly the kind of things that literature and art should explore. By banning it you are not protecting people but patronising them by refusing their right to judge it for themselves.”

This article was posted on 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org