Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The usually bustling entrance of the New Broadcasting House in London was still filled to the brim with people this morning, but for one minute they were completely silent.

BBC staff, joined by fellow journalists from around the world, stood in silent protest at 9:41 am, exactly 24 hours from the sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists to prison in Egypt. Peter Greste and Mohamed Fahmy were each handed down seven-year sentences, while Baher Mohamed was given ten years.

The three journalists were found guilty on Monday for spreading false news by a court in Cairo. Ten other journalists, including Al Jazeera’s Sue Turton and Dominic Kane, and Rena Netjes, a correspondent for Dutch newspaper Parool, were also sentenced in absentia to ten years.

The silent protest was orchestrated in hopes of fighting against these unjust practices and to raise awareness of the dangers and censorship many international journalists face.

BBC Director of News, James Harding, stood up and addressed the group: “They are not just robbing three innocent men of their freedom, but intimidating journalists and inhibiting free speech.”

The protestors held signs that read #FreeJournalism and #FreeAJStaff, and covered their mouths with tape in order to illustrate their frustration with the trial verdict.

Sana Safi, a presenter for BBC Pashto TV News, said: “When I heard the verdict, I was in shock because I’m from Afghanistan and we have seen more media freedom in the last few years, and I wasn’t expecting anything like that from a country like Egypt.”

Their looks were determined and their heads were held high as cameras flashed and captured the intense moment. Cowardice was not an option.

Nasidi Yahaya, a social media producer from BBC Hausa, said: “The verdict was so unfair, these guys were just doing their job. Journalists should not be silenced like this.”

The journalists from the BBC, Al Jazeera, and other news organisations standing together in solidarity will also be sending a letter calling on the Egyptian president to intervene in the situation.

The wait for their freedom begins.

This article was posted on 24 June, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

The sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists today took Michelle Betz back to her own trial.

Just over a year ago I was awoken around 5am in Washington by a call from my Egyptian colleague. “Guilty,” he breathed. “We are all guilty”. I could hear the shock in his voice. I couldn’t yet feel my own shock.

We were defendants in the NGO trial in which 43 people working for four US and one German NGOs were accused of charges including operating without a licence and bringing foreign funds into the country. There were so many ironies about the case, the trial, and the charges; so many outrages; so many injustices. There were many, many parallels with what is happening now with the Al Jazeera journalists.

There was little international noise around our “trial”. And that is the one thing that has been different with the Al Jazeera trial – at least there has been no silence.

At the time I was working with the International Center for Journalists, from Washington DC. Judicial officials didn’t even have my full name, but there I was number 39 on the charge document.

I knew full well one year ago that we would be found guilty despite the multitude of assurances from all corners: the NGOs, the US State Department, the lawyers – all tried to assure us that this was all political (between the US and Egypt) and that this would “all go away”. Of course, logically, this should have all gone away. Just as with the Al Jazeera case, logically, it never should have happened. Logically, we, as they, should have been found innocent.

But dealing with the Egyptian judicial system is anything but logical.

In neither case was there any evidence and in neither trial did the prosecution have any legitimate case. But that was beside the point. They didn’t need evidence. They didn’t need a case. All they needed to do was follow the directive from on high and read the verdict: guilty.

I lived in Egypt for three years and I can never go back. If I did I would be immediately imprisoned.

Some have expressed surprise at the speed with which today’s verdict was rendered asking how the judge could possibly have written his judgment in so short a time. He didn’t. Instead, it’s highly likely that the judgment was already written six months ago. The judge was simply doing what he was told. I too would have worn sunglasses to court today; I too would have dragged my feet getting to work for surely there was some weight on his conscience.

So what now? The Egyptians learned from our case. At least in the NGO case none of us were imprisoned, though Egypt did pursue some of us through Interpol. The one thing the US did was to get all Americans (save one hero, Robert Becker, who refused to leave his Egyptian colleagues facing trial alone) first to the US Embassy in Cairo (where they stayed for days) and then finally flew them out in the middle of the night after some backroom deal was worked out with Egyptian officials.

And the Egyptian establishment has learned from this. They learned not to allow bail to prevent defendants leaving Egypt. They learned that the US (and the international community at large) didn’t care and that there would be no repercussions even if American citizens were convicted and sentenced to five years of hard labor. They learned that even the media didn’t care.

But on that last point they miscalculated – they didn’t realise that there is a tribe of journalism, which does not suffer injustice and attacks on its own. And that is our hope at this point – that we raise our voices, we continue to speak the truth, we continue to point to injustices, including injustices wrought on our tribe. For if we are silenced, then we all face injustice.

Yes, of course there was no evidence and of course the prosecution had no case. And so today we find ourselves one year on watching in horror as three Al Jazeera journalists are convicted and sentenced to 7-10 year prison sentences and those convicted in absentia to an even lengthier sentence (just like those convicted in absentia in the NGO trial, such as myself, who received longer sentences).

And so while my colleagues were shocked by our verdict one year ago, I was not. And if we were found guilty then so too would our Al Jazeera colleagues. There was a message to be sent.

But the convictions should be no surprise. Rule of law in Egypt as always been tough to find but almost any remaining semblance of it disappeared with the coup of 2013.

This article was posted on June 23, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Index on Censorship condemns the sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt to seven years each in prison. Peter Greste, Mohammed Fahmy and Baher Mohamed were sentenced today to seven years imprisonment under accusations of spreading false news and supporting the Muslim Brotherhood. The journalists were detained on 29 December 2013.

“Today’s verdict is disgraceful,” Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg said. “It tells journalists that simply doing their job is considered a criminal activity in Egypt. We call on the international community to join us in condemning this verdict and ask governments to apply political and financial pressure on a country that is rapidly unwinding recently won freedoms, including freedom of the press. The government of newly elected president Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi must build on the country’s democratic aspirations and halt curbs on the media and the silencing of voices of dissent.”

The court’s decision comes as a severe setback for all journalists currently jailed or prosecuted for doing their job, and reinforces claims of a politicised judiciary in Egypt. Other defendants in the case, who were tried in absentia, got sentenced to 10 years.

Index is deeply concerned at the growing number of imprisoned journalists in Egypt and around the world. At least 14 journalists remain in detention in Egypt and some 200 journalists are in jail across the globe. Many of those arrested in Egypt were reporting on protests following the ousting of Mohamed Morsi or the passing of a controversial anti-protest law.

We reiterate our support to journalists to report freely and safely and call on Egyptian authorities to drop charges against journalists and ensure they are set free from jail. And we ask governments to maintain pressure on Egypt to ensure freedom of expression and other fundamental human rights are protected. Index joined the global #FreeAJStaff campaign along with other human rights, press freedom groups and journalists.

It is still hot in the shade of the palm trees and stuccoed buildings on the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) downtown campus. Groups of refugees sit around on wicker chairs.

It is still hot in the shade of the palm trees and stuccoed buildings on the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) downtown campus. Groups of refugees sit around on wicker chairs.

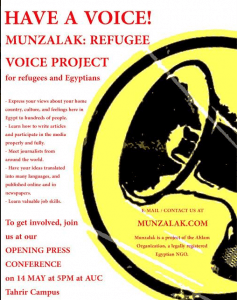

Everyone is here to learn about journalism. Munzalak is a new organization that aims to get refugees living in Egypt involved in the media and in command of their own voice. The name translates to “your comfortable place,” like a home from home – the one you were forced to leave.

Every weekend Munzalak hires out a room at AUC. Refugees are invited to come along and learn the basics of journalism for free. Aurora Ellis, a news editor for an international news agency, runs the workshops with aim of producing “articles that deal with refugee issues and with the refugee experience.”

The ultimate aim is to give refugees a space to voice their experiences. A blog on Munzalak’s website publishes pieces written by refugees (with the option of writing under a pseudonym) while training goes on and – organizers hope – more people join.

Similar initiatives have existed. The Refugee Voice was a newspaper based in Tel Aviv run by African asylum seekers and Israelis inside Israel and founded in April 2011, but is no longer published. Radar, a London-based NGO, also trains local populations in areas around the world (including Sierra Leone, Kenya and India) with the aim of connecting isolated communities.

“We’re being given the opportunity to write about our experiences…I can write about my experiences, and interview other refugees about theirs,” says Edward, a Sudanese refugee who arrived in Cairo earlier this year.

“We have several basic problems – in housing, security, education and health.” He quietly tells stories of life in Egypt; harassment and assault in the streets and pervasive racism (even, he says, from some people who are there to help). “We live a separated life. We are here by force only.”

Ultimately, Edward wants to write a history of the Nuba Mountains, the war-torn area straddling the border between Sudan and South Sudan, where he was born in over 25 years ago. Edward carries a notebook with ideas for this book – scribbled notes of a people and culture disappearing; histories of war and exodus. Edward sees his journalism as self-preservation, telling stories that other people don’t want to be told. He most admires Nuba Reports, a non-profit news source staffed by Sudanese reporters, which aims to break reporting black-spots while humanitarian crises and fighting continues on the ground.

Some activists working alongside refugees see initiatives like this as an important way to break the silence.

“Before June 30, refugees were always neglected in the national media. They were only included [the media] if they were being used as scapegoats,” says Saleh Mohamed from the Refugee Solidarity Movement (RSM) in Cairo. Famous examples include right-wing TV host Tawfik Okasha calling for Egyptians to arrest and attack Syrian and Palestinian refugees on sight. Syrians and Palestinians arrested by security forces have been routinely referred to as “terrorists” by the authorities, a narrative often repeated verbatim by pro-regime newspapers. “Now I think the media wants to keep refugees in the shadows and not talk with them,” Mohamed adds. “You never hear about refugees.”

But Munzalak is not without its risks and challenges. Staying independent but still being able to attract funding and support is one thing. Another is security.

Last Sunday 13 Syrians were sentenced to five years in prison after protesting in March 2012 against Bashar al-Assad. They were charged with illegal assembly and “threatening…security [forces] with danger,” something the defendants all denied, according to state-run newspaper Al-Ahram. A UNHCR official last year had told Syrian refugees to stay away from domestic politics – a warning that could feasibly include journalism as well.

Although historically repressive towards journalists during the rule of Hosni Mubarak, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s media landscape has taken a significant nosedive since the July coup. Several journalists have been killed in the violence; Mayada Ashraf, a young reporter for Al-Dostour became the latest casualty after she was shot in the head during a protest, allegedly by a police sniper; while reporters remain behind bars and on trial for doing their job.

So is it a good idea to get refugees involved?

Mohamed says that street reporting and visibly working as journalists could put refugees – like Edward – “in danger.” Their legal ability to work also depends on what refugee status they have.

“But otherwise they can talk about themselves rather than waiting for journalists to approach them instead…They definitely need a voice.” But for some refugees, other priorities come first.

Jomana is a 20-year-old Syrian refugee and media studies undergraduate, originally from Aleppo. She visited Munzalak once and liked the idea, but is more concerned about getting a job and paying her way than talking about her experiences – which, like so many Syrian refugees in Egypt nowadays, are harsh. Of almost 184,000 refugees living in Egypt, according to mid-2013 figures from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), around 130,000 of that number are Syrians.

“I don’t have enough money to continue my studies so I will have to leave,” she explains plainly. Jomana’s home was bombed out during the war and they fled the country with just their passports, arriving in Cairo over two years ago. Eventually her father went back to Aleppo to try and restart his old factory, but returned to find rubble. He came back to Cairo to economic uncertainty, incitement and political instability. “Other people are going back to Syria and dying there. Those that stay [here] aren’t dying from bombing or from fighting…but from hunger.”

Munzalak might help, but for some refugees, not in the most crucial of ways.

“It means I can express my opinion freely,” Jomana says, “but will I get paid for my opinion?”

This article was published on June 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org