12 Jun 2014 | Cameroon, Iran, News and features, Nigeria, Russia

The 2014 World Cup in Brazil starts today, 32 nations preparing to battle it out across eight groups in the first stage of the tournament.

This year’s competition, like so many before it, comes with its designated group of death. For those not familiar with the lingo, it means the group containing the highest amount of strong teams. Or even more simply put, the group most difficult to progress from. (You can’t accuse the beautiful game of holding back on the melodrama).

Index has looked at the countries taking part in arguably the biggest show on earth, and put together our own group of death — the freedom of expression edition.

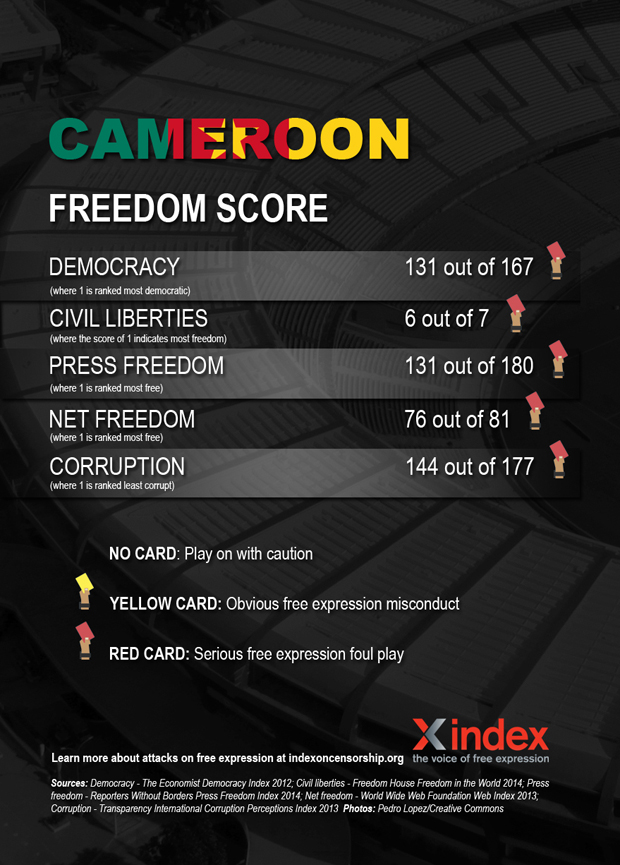

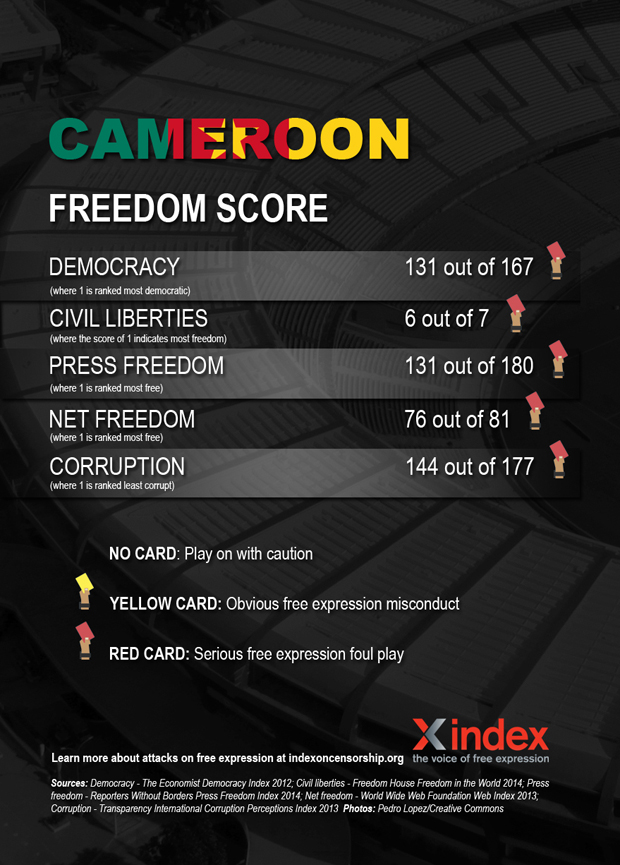

Cameroon

Cameroon — or the Indomitable Lions — have a solid track record in qualifying for the World Cup, having taken part seven time, more than any other African side. There were also the first African team to make it to the quarter final and are responsible for one of the most iconic moments in the tournament’s history. Their track record on free speech, however, is less impressive.

Freedom of expression is guaranteed in Cameroon’s constitution. Despite this, the government of Paul Biya — the country’s leader since 1982 — has been been accused numerous violations of free expression.

Large parts of the press are biased towards the ruling elite, while critical journalists face detainment, harassment and demands to reveal sources, among other things. Self censorship is widespread. In September 2013, 11 press outlets, including newspapers, radio stations and a TV station, were shut down for disrespecting “ethics and professional norms”. In 2010, former newspaper editor Germain Ngota, who had been investigating corruption allegations involving the state-run oil company, died in jail.

Freedom of assembly is often cracked down on. In 2012, former opposition presidential candidate Vincent-Sosthène Fouda and others were charged with “holding an unlawful demonstration”. The same year, security forces used tear against a crowd gathered to protest against Biya. In 2008, around 100 people were killed in clashes with police in anti-government riots.

Arts are not spared either. In 2013, Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s film Le President was banned in Cameroon because it discussed the end of Biya’s reign . In 2008, Lapiro de Mbanga, who criticised the constitutional change in term times that would allow Biya to stay in powers through song, was arrested.

Homosexuality is outlawed, and punishable by up to 14 years in prison. Human rights violations against LGBTI people, or those perceived to be, are “commonplace”. In July 2013, Eric Ohena Lembembe, director of the Cameroonian Foundation for AIDS (CAMFAIDS) was brutally murdered, in what friends suspect was an attack based on his pro-LGBTI advocacy.

Iran

Team Melli will hope that their fourth appearance at the World Cup will see them progress from the group stages for the first time. When he was elected almost a year ago, there was hope that President Hassan Rouhani would be a progressive force within Iran. The results so far have been mixed.

Since coming into power, Rouhani has taken some steps to improve press freedom, such as withdrawing 50 motions against journalists, and lifting some restrictions on previously banned topics. However, the government still controls all TV and radio, and censorship and self-censorship is widespread. The latest figures put the number of jailed journalists in Iran at 35. In January 2013, a group of journalists were arrested for allegedly cooperating with “anti revolutionary” news outlets abroad. Journalists’ associations and civil society organisations that support freedom of expression have also been targeted.

The internet and social media played a significant part in publicising and documenting the protests that followed the 2009 election, which many Iranians believed was fraudulent. The regime has banned Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and, recently, Instagram. The lead-up to the 2013 elections saw Iranian leaders tightening access to the web, and silencing “negative” news. While Rouhani — seemingly an avid Twitter user — has indicated plans to relax web censorship, the country’s plans to launch a “national internet” are said to be going ahead.

In May, eight people were jailed on charges including blasphemy, propaganda against the ruling system, spreading lies insulting the country’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Facebook. Recently, a group of young people were arrested over a video posted of them singing and dancing along to the song “Happy”, which police called was a “vulgar clip” that had “hurt public chastity”. Some commentators believe the move was meant to intimidate Iranians and discourage online criticism.

Nigeria

Brazil 2014 marks 20 years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup, and the Super Eagles arrive at the tournament as reigning Africa Cup of Nations champions. The country’s leadership, however, is not a champion of free expression.

While parts of Nigerian media is controlled by people directly involved in politics, the country can also boast a lively independent media sector. However, journalists, especially those covering sensitive topics such as corruption or separatist and communal violence still face threats. Journalists have been arrested by security forces, and media outlets have been attacked by terrorists. Legal provisions such as sedition and criminal defamation also challenge press freedom. In 2011, a journalist was arrested over stories detailing alleged corruption in the Nigerian Football Federation.

The country’s freedom of information act was put in place in 2011. However, when human rights lawyer Rommy Mom tried to use the legislation to trace some 500 million of missing aid money allocated to his flood ravaged home state of Benue, he was met with threats from people connected to the state governor, and was forced to flee.

The Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act 2013 outlawing gay marriage and relationships, was signed into law by President Goodluck Jonathan in January. The unpublished law makes it illegal for gay people to hold meetings, and outlaws the registration of homosexual clubs, organisations and associations. Those found to be participating in such acts face up to 14 years in jail.

Nigeria has come under international attention in recent months for abduction of the Chibok school girls by terrorist group Boko Haram. Among other things, Nigerians responded with the powerful #BringBackOurGirls campaign. In June however, authorities seemed to ban an offline protest against the kidnappings, before quickly backtracking. It is also worth noting that the Nigerian government has targeted journalists in their “war on terror”.

Russia

Team Sbornaya travel to Brazil in the knowledge that next time in the World Cup rolls around, they will be playing on home soil. Russia of course, recently hosted another international sporting event — the 2014 Winter Olympics. However, global attention did not improve the country’s poor record on freedom of expression. In fact, experts predicted a rise in censorship ahead of the Olympics.

Press freedom has long been under attack by Russian authorities, with TV news currently providing little beyond the official government line. In the last few months, the relatively well-respected TV channel RIA Novosti was liquidated following a decree by President Vladimir Putin, and replaced by a new press agency headed by a Kremlin-loyalist. In January, Dozhd, a popular independent TV channel was dropped by satellite and cable operators over a controversial survey. For the remaining critical journalists, Russia — one of the countries with the highest number of unpunished journalist murders — is a dangerous place to work.

The crackdown on the internet is widely believed to have started with the protests surrounding the elections securing Putin’s third term in power, organised partly through social media, but it has recently intensified. The Duma has adopted controversial amendments to an information law, targeting bloggers with blocking and fines for anything from failing to verify information posted, to using curse words. Also recently, the founder of “Russian Facebook” VKontakte says he was forced out, with the son of the head of Russia’s largest state-run media corporation predicted to take over as CEO. In 2013, the Duma approved legislation allowing immediate blocking of websites featuring content deemed “extremist”.

Public protests are discouraged through forceful responses by police, arrests, harsh fines and prison sentences. The country’s recent anti-gay legislation also pose a big threat to free expression and assembly. The ban on “promotion” of gay relationships, means that any form of expression deemed to be “gay propaganda” can be shut down. The law has also lead to physical attacks on Russia’s LGBT population.

An earlier version of this article stated that Brazil 2014 marks ten years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup. This has been corrected.

This article was published on June 12, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Jun 2014 | Azerbaijan News, Digital Freedom, News and features

(Image: Bplanet/Shutterstock)

Croatia’s new criminal code has introduced “humiliation” as an offence — and it is already being put to use. Slavica Lukić, a journalist with newspaper Jutarnji list is likely to end up in court for writing that the Dean of the Faculty of Law in Osijek accepted a bribe. As Index reported earlier this week, via its censorship mapping tool mediafreedom.ushahidi.com: “For the court, it is of little importance that the information is correct – it is enough for the principal to state that he felt humbled by the publication of the news.”

These kinds of laws exist across the world, especially under the guise of protecting against insult. The problem, however, is that such laws often exist for the benefit of leaders and politicians. And even when they are more general, they can be very easily manipulated by those in positions of power to shut down and punish criticism. Below are some recent cases where just this has happened.

Tajikistan

On 4 June this year, security forces in Tajikistan detained a 30-year-old man on charges of “insulting” the country’s president. According to local press, he was arrested after posting “slanderous” images and texts on Facebook.

Iran

Eight people were jailed in Iran in May, on charges including blasphemy and insulting the country’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Facebook. They also were variously found guilty of propaganda against the ruling system and spreading lies.

India

Also in May this year, Goa man Devu Chodankar was investigated by police for posting criticism of new Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Facebook. The incident was reported the police someone close to Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), under several different pieces of legislation. One makes it s “a punishable offence to send messages that are offensive, false or created for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience”.

Swaziland

Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu were arrested in March this year, and face charges of “scandalising the judiciary” and “contempt of court”. The charges are based on two articles, written by Maseko and Makhubu and published in the independent magazine the Nation, which strongly criticised Swaziland’s Chief Justice Michael Ramodibedi, levels of corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

Venezuela

In February this year, Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez was arrested on charges of inciting violence in the country’s ongoing anti-government protests. Human Rights Watch Americas Director Jose Miguel Vivanco said at the time that the government of President Nicholas Maduro had made no valid case against Lopez and merely justified his imprisonment through “insults and conspiracy theories.”

Zimbabwe

Student Honest Makasi was in November 2013 charged with insulting President Robert Mugabe. He allegedly called the president “a dog” and accused him of “failing to do what he promised during campaigns” and lying to the people. He appeared in court around the same time the country’s constitutional court criticised continued use of insult laws. And Makasi is not the only one to find himself in this position — since 2010, over 70 Zimbabweans have been charged for “undermining” the authority of the president.

Egypt

In March 2013, Egypt’s public prosecutor, appointed by former President Mohamed Morsi, issued an arrest warrant for famous TV host and comedian Bassem Youssef, among others. The charges included “insulting Islam” and “belittling” the later ousted Morsi. The country’s regime might have changed since this incident, but Egyptian authorities’ chilling effect on free expression remains — Youssef recently announced the end of his wildly popular satire show.

Azerbaijan

A recent defamation law imposes hefty fines and prison sentences for anyone convicted of online slander or insults in Azerbaijan. In August 2013, a court prosecuted a former bank employee who had criticised the bank on Facebook. He was found guilty of libel and sentenced to 1-year public work, with 20% of his monthly salary also withheld.

Malawi

In July 2013, a man was convicted and ordered to pay a fine or face nine month in prison, for calling Malawi’s President Joyce Banda “stupid” and a “failure”. Angry that his request for a new passport was denied by the department of immigration, Japhet Chirwa “blamed the government’s bureaucratic red tape on the ‘stupidity and failure’ of President Banda”. He was arrested shortly after.

Poland

While the penalties were softened somewhat in a 2009 amendment to the criminal code, libel remains a criminal offence in Poland. In September 2012, the creator of Antykomor.pl, a website satirising President Bronisław Komorowski, was “sentenced to 15 months of restricted liberty and 600 hours of community service for defaming the president”.

This article was published on June 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

13 May 2014 | Asia and Pacific, News and features, North Korea

Gymnasts at Arirang festival in Pyongyang, North Korea (Image: Roman Kalyakin/Demotix)

Jang Jin-sung, formerly poet laureate for North Korea, is one of its highest-ranking defectors and most vocal critics. A meteoric career that saw him also become chief propagandist in the United Front Department, engaging in counter-intelligence and psychological warfare against South Korea, he was also one of Kim Jong Il’s inner circle — a dreamlike life of privilege shattered when he found the bodies of famine victims lying in the streets of his home town. Facing almost certain death for the crime of mislaying a prohibited text, he dramatically escaped to China in 2004 and defected to South Korea. Based on his insights from working in the elite, he argues that the official narrative of North Korea being run under the absolutist genius of the Kim dynasty and the Korean Workers Party, is a lie. Power was not harmoniously transferred upon Kim Il Sung’s death in 1994 to his son, Kim Jong Il — instead Kim Jong Il had long before usurped his father with the support of the clandestine Organisation and Guidance Department (OGD), while Kim Il Sung spent his last years under virtual house arrest, bamboozled by his own cult, created by his son. Kim Jong Il directed the OGD under his reign and he legitimised “every single policy and proposal, surveillance purge, execution, song and poem”, but upon his death in 2011, however, the bequest of leadership upon his son Kim Jong Un was solely symbolic; the OGD took charge. That year, Jang set up New Focus International to give insight and analysis to North Korea. This week he talked about the OGD as “the single most powerful entity in North Korea” to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on North Korea. His words were translated by NFI’s international editor, Shirley Lee, and the talk was chaired by Lord David Alton.

The OGD is “the entity that controls everything. This is where all roads end, all chains of command, and all power structures go,” Jang said. “The real power structure, nothing has changed since Kim Jong Il’s time. The OGD is still just as it is, the same men are in the same positions of power.” Yet the OGD is so secret and compartmentalised a structure, it’s only fully comprehended by the most senior leaders, and known to “less than a dozen” of the approximate 26,000 refugees out of North Korea. That lack of knowledge has meant that traditionally, outside observers omitted the OGD’s existence, basing their views on diplomatic notes, refugee testimonies and political theories which Pyongyang has successfully fed into with propaganda about the Kims’ omnipotence, to obscure its power structures. Hence, many observers interpreted the purge of Kim Jong Un’s uncle Jang Song Thaek as the new leader getting rid of his old guard to make his own power network, whereas it was really the OGD liquidating a rival. South Korea has also connived to keep a lid on knowledge of the OGD. When Hwang Jong Op, the international secretary of the Korean Workers’ Party and principal author of the state philosophy of Juche, defected and sought to tell of the OGD, the South’s then Sunshine Policy “was based on a policy of engagement that sought not to provoke the North Korean regime, [so] they actually silenced his testimony from appearing,” said Jang.

Whereupon while “every single person seen as the second, third, fourth most powerful man, has been purged or destroyed … every single powerful member of the OGD has remained”. They will stay in power as the OGD is in effect North Korea’s “human resources department, it appoints everyone”. The vetting of appointees is based on trust, and loyalty secured by cadres knowing any perception of disloyalty will imprison them, their parents and their children. “No-one is exempt from this… because no matter how big you are, if you do something wrong, you are sending your family to prison camp to rot away for the rest of their lives, never to be seen again.” As Lee put it, “you’re not going to kill your own family to change that”. Jang himself has tried many times to contact his parents in North Korea, but has never succeeded. “You can’t begin to think about what his parents may be suffering but that just makes him stronger,” said Lee.

The OGD appoints all generals and makes all military orders, with the military’s autonomy compromised like everything else by the OGD’s all-pervasive surveillance structure. Party committees of spies are installed across all sectors from diplomacy to tourism, down to each and every apartment block — “the OGD has eyes and ears everywhere”. It is backed by the OGD’s secret police and system of prison camps that the group developed into a weapon of mass terror while it usurped Kim Il Sung. He was prevented from seeing friends or family by his OGD-appointed bodyguards, a corps now numbering 100,000. He “died as a scarecrow, he was nothing,” said Lee.

As well as these physical means of control, the state seeks to monopolise all information flows and uses incredible psychological and emotional force to ensure its citizens’ loyalty. “In North Korea the only politically correct faith to have is in the cult of the Kims,” said Jang, while religious organisations like the Chosun Association or Buddhist association are run by the UFD, and Christians end up in prison camps. “The only narrative that matters is of the righteous sovereignty of the state.”

Yet for all the surface illusion of power, the nuclear weapons, the police and prison system, “it is a country that’s ruined inside, it’s a collapsed state. They do not control the price of an egg, and that is a huge deal”. Black markets have almost entirely supplanted the government monopoly of provision of goods, ranging from clothing to food, which collapsed in the mid-1990s as millions perished in the famine. This has created two classes, those loyal to the party because of their stake in the status quo; and the market class of people who were abandoned by the state and survive on the black market. Critically, this means that for promotions, status, power or material wealth, “the currency has converted from loyalty to money,” said Jang, “and that has broken the cult of North Korea for everyone”.

Economic “reforms” are really state efforts to try control the black markets, which have at times suffered violent crackdowns, for having become “a black hole that sucked in the control mechanisms of the state”. Equally, however, the regime cannot survive without them, as “the market feeds the people”. The country is also suffering from criminal activities actually sanctioned by the regime, namely counterfeit dollar bills, meth amphetamine production and computer hacking. “It’s not the world that’s suffering, the country is being destroyed by the regime’s own creations,” as government computers are hacked and fake bills and drugs run through society. Refugee statements say meth amphetamine abuse has become “just part of the ordinary life”.

Meanwhile the markets live off information. “The price of rice, the price of your life rises and falls in terms of knowing outside world information…ordinary people know it’s an advantage to listen to the outside world [information],” and Jang endorses the set up of a BBC Korea service to broadcast into North Korea. “The only way to break the dictatorship of force is by breaking that emotional monopoly over the people… There is no more effective tool that the world can do than to acknowledge that the North Korean people have the right to another narrative than that the party supplies.”

“More important is that no one in the North today believes it will last for ever,” but “the one thing that is stopping them from acting is there is no other way. Everyone is trying to do it the regime’s way”. This extends from efforts to deal with Pyongyang’s nuclear bomb program, which fail because international frameworks don’t apply to North Korea — “the only way the world can resolve the nuclear problem is seeing the regime transform. You can’t do it within their demands” — to the country’s appalling human rights record. “Those who think putting human rights on the agenda would jeopardise engagement and dialogue are wrong. North Korea is more desperate for dialogue at the state level than the West is. They [the North Korean state] need that to sustain what is happening right now.” Putting human rights atop all agendas would mean “there is nowhere left for the North Korean leadership to stand”.

“Stop looking at the regime as the agent of positive transformation,” said Jang, and engage with those with no stake in the status quo. Meanwhile, China, as the North’s sole supporter, is key to its survival and to brook any change. “China supports North Korea because it’s more convenient to support it than not,” said Jang, adding that Kim Jong Il hated China more than anybody “because he was at their mercy”, while Beijing’s anger at Jang Song Thaek’s execution was because it was “like the nightmare of Kim Jong Il would continue”. On Wednesday China warned North Korea against carrying out another nuclear test. And while China has yet to host Kim Jong Un, it has already welcomed South Korea’s President Park with open arms. Repeatedly reaffirming North Korea’s human rights record, damningly detailed by the United Nations’ Commission of Inquiry Into Human Rights in the DPRK in March, to the Chinese government may pressure them into giving up the forceful repatriation of North Korea refugees, which leads to prison or death, according to Lord Alton. “The scariest thing for China is to start to get moral blame for what’s going on in North Korea. So it will want to be seen to be doing the right thing.” On that, Jang said any retribution befalling the regime for human rights abuses, “the OGD will blame will Kim Jong Un alone”.

Again it’s an issue of perception. “In North Korea, I thought change could not come because the regime was so powerful. When I came to South Korea I learned that North Korea was not transformed because the South Koreans didn’t know it could.” Indeed, “the only thing holding North Korea back from transforming is that the world isn’t ready for it.”

The talk was organised with help from the European Alliance for Human Rights in North Korea. Jang’s book Dear Leader (UK Random House, US, Simon & Schuster) is out now.

This article was posted on May 13, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 May 2014 | News and features

A London protest calling for the release of jailed Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt (Image: Index on Censorship)

Press freedom is at a decade low. Considering just a handful of the events of the past year — from Russian crackdowns on independent media and imprisoned journalists in Egypt, to press in Ukraine being attacked with impunity and government reactions to reporting on mass surveillance in the UK — it is not surprising that Freedom House have come to this conclusion in the latest edition of their annual press freedom report. This serves as a stark reminder that press freedom is a right we need to work continuously and tirelessly to promote, uphold and protect — both to ensure the safety of journalists and to safeguard our collective right to information and ability to hold those in power to account. On the eve of World Press Freedom day, we look back at some of the threats faced by the world’s press in the last 12 months.

1) Journalism is not terrorism…

National security has been used as an excuse to crack down on the press this year. “Freedom of information is too often sacrificed to an overly broad and abusive interpretation of national security needs, marking a disturbing retreat from democratic practices,” say Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in their recently released 2014 Press Freedom Index.

Journalists have faced terrorism and national security-related accusations in places known for their somewhat chequered relationship with press freedom, including Ethiopia and Egypt. However, the US and the UK, which have long prided themselves on respecting and protecting civil liberties, have also come under criticism for using such tactics — especially in connection to the ongoing revelations of government-sponsored mass surveillance.

American authorities have gone after former NSA contractor and whistleblower Edward Snowden, tapped the phones of Associated Press staff, and demanded that journalists, like James Risen, reveal their sources. British authorities, meanwhile, detained David Miranda under the country’s Terrorism Act. Miranda is the partner of Glenn Greenwald, the journalist who broke the mass surveillance story. Authorities also raided the offices of the Guardian — a paper heavily involved in reporting in the Snowden leaks.

2) …but governments still like putting journalists in prison

The Al Jazeera journalists detained in Egypt on terrorism-related charges was one of the biggest stories on attacks on press freedom this year. However, Mohamed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed, Peter Greste and their colleagues are far from the only journalists who will spend World Press Freedom Day behind bars. The latest prison census from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) put the number of journalists in jail for doing their job at 211 — their second highest figure on record.

In Bahrain, award-winning photographer Ahmed Humaidan was sentenced in March to ten years in prison. In Uzebekistan, Muhammad Bekjanov, editor of opposition paper Erk, is serving a 19-year sentence — which was increased from 15 in 2012, just as he was due to be released. In Turkey, after waiting seven years, Fusün Erdoğan, former general manager of radio station Özgür Radyo, was last November sentenced to life in jail. Just last Friday, Ethiopian authorities arrested prominent political journalist Tesfalem Waldyes and six bloggers and activists.

3) New media is under attack…

As more journalism is being conducted online, blogs, social and other new media are increasingly being targeted in the suppression of press freedom. Almost half of the world’s jailed journalists work for online outlets, according to the CPJ. China — with its massive censorship apparatus — has continued censoring microblogging site Sina Weibo, while also turning its attention to relative newcomer WeChat. In March, it closed down several popular accounts, including that of investigative journalist Luo Changping.

Meanwhile, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has publicly all but declared war on social media, at one point calling it the “worst menace to society”. Twitter played a big role in last summer’s Gezi Park protests, used by journalists and other protesters alike. Only days ago, Turkish journalist Önder Aytaç was jailed, essentially, because of the letter “k” in a Tweet.

Meanwhile Russia has seen a big crackdown on online news outlets, while legislation recently passed in the Duma is targeting blogs and social media.

4) …and independent media continues to struggle

Only one in seven people in the world live in countries with free press. In many parts of the world, mainstream media is either under tight control by the government itself or headed up media moguls with links to those in power, with dissenting voices within news organisation often being pushed out. Brazil, for instance, has been labelled “the country of 30 Berlusconis” because regional media is “weakened by their subordination to the centres of power in the country’s individual states”. At the start of the year, RIA Novosti — known for on occasion challenging Russian authorities — was liquidated and replaced by the more Kremlin-friendly Rossiya Segodnya (Russia Today), while in Montenegro, has seen efforts by the government to cut funding to critical media. This is not even mentioning countries like North Korea and Uzbekistan, languishing near the bottom of press freedom ratings, where independent journalism is all but non-existent.

5) Attacks on journalists often go unpunished

A staggering fact about the attacks on journalists around the world, is how many happen with impunity. Since 1992, 600 journalists have been killed. Most of the perpetrators of those crimes have not been brought to justice. Attacks can be orchestrated by authorities or by non-state actors, but the lack of adequate responses by those in power “fuels the cycle of violence against news providers,” says RSF. In Mexico, a country notorious for violence against the press, three journalists were murdered in 2013. By last October, the state public prosecutor’s office had yet to announce any progress in the cases of Daniel Martínez Bazaldúa, Mario Ricardo Chávez Jorge and Alberto López Bello, or disclose whether they are linked to their work. Pakistan is also an increasingly dangerous place to work as a journalist. Twenty seven of the 28 journalists killed in the past 11 years in connection with their work have been killed with impunity. Syria, with its ongoing, devastating war, is the deadliest place in the world to be a journalist, while some of the attacks on press during the conflict in Ukraine, have also taken place without perpetrators being held accountable. That attacks in the country appear to be accelerating, CPJ say is “a direct result of the impunity with which previous attacks have taken place”.

This article was published on May 2, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org