Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

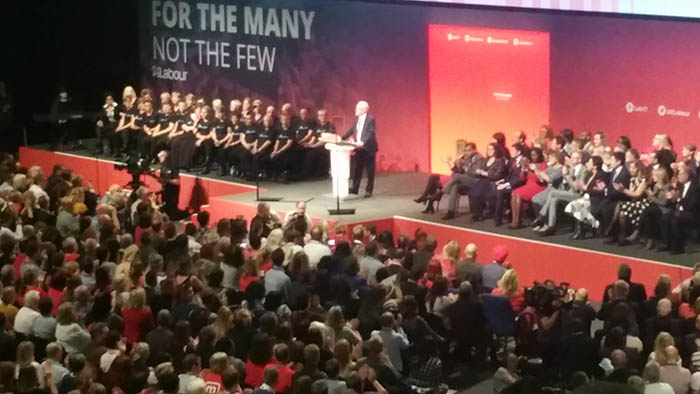

Jeremy Corbyn speaks at Labour Party conference in Brighton, September 2017. Credit: DaveLevy/Flickr

During his first speech at conference as Labour Party leader in September 2015, Jeremy Corbyn called for an end to “personal abuse” and urged delegates to “treat people with respect”.

“Cut out the cyber-bullying and especially the misogynistic abuse online,” he added. “I want kinder politics.”

Two years on the message hasn’t gotten through.

On 24 September 2017, the second day of this year’s party conference, BBC political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned bodyguards after receiving abusive threats online.

The BBC had also decided to bolster Kuenssberg’s personal protection during the general election in June after she faced threats over alleged bias in her reporting surrounding Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. She has also been accused of partiality by Conservative and Ukip supporters.

“It is unprecedented that a journalist would need protection to do her job covering a political conference in the UK, which makes this all the more troubling,” Hannah Machlin, project manager for Index on Censorship’s’ Mapping Media Freedom project, said. “Laura’s case indicates that sexist online abuse against women journalists has become part of the job, and it’s affecting not only the safety of reporters but also a functioning free press.”

Two other journalists were refused entry altogether to the conference. On 23 September, Sussex police refused to give Huck magazine editor Michael Segalov a press security clearance required to attend. Segalov wrote that he applied for press accreditation three months prior to the conference but was informed the evening of 19 September that it had been denied based on the police’s refusal to grant him security clearance.

“Rather than provide reasons and rationale for our journalistic freedom being curtailed, the police said they would not divulge why they made their call,” Segalov wrote. He has never been arrested, charged or convicted of any crime.

“This might be a single incident, but the repercussions should it go unchallenged are worrying. The police restricting the rights of a journalist from attending a political event without giving any rationale, basis or reason puts our civil liberties on the line.”

On 24 September, Michael Walker, a left-wing journalist working for Novara Media, was also barred from entering by police.

“Barring reporters is a form of censorship,” Machlin added. “Political parties interfering with access to events undermines key parts of democracy and sends a clear message from the labour party to all other journalists.”

Earlier this year, Corbyn’s press team barred Buzzed from campaign events. On 9 May, in the run-up to the general election, a senior Corbyn aide told BuzzFeed News political editor Jim Waterson that his access was limited and that the website’s access to the Labour leader would be limited for the rest of the campaign. This was because of an interview with Corbyn published on 8 May had “disrupted media coverage of Labour’s launch event”, the website reported.

Buzzfeed published a piece quoting Corbyn that he remain as the party’s leader even if he lost the election. Corbyn told the BBC he had only said he would stay in power because they would win. BuzzFeed then published an extract of the interview, which showed they had quoted him accurately.

Waterson later regained access to the leader.

Such violations to media freedom are not limited to the Labour Party, however. Also in the run-up to the election, three journalists for Cornwall Live were shut in a room, prevented from filming and severely limited on what questions they could ask during Conservative prime minister Theresa May’s visit to a factory in Cornwall.

A reporter from Cornwell Live who was live-blogging the event wrote: “We’ve been told by the PM’s press team that we were not allowed to stand outside to see Theresa May arrive.”

On two occasions in April 2017, Conservative-run Thurrock Council in Essex said they would restrict access to journalists who “do not reflect the council’s position accurately”.

In the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire in June, the Kensington and Chelsea Council, which has been Conservative-run since 1964, tried to prevent journalists from attending its first after the atrocity. The council had sought to exclude the public and media from the cabinet meeting, arguing their presence would risk disorder. But after a legal challenge from five media organisations, a high court judge ordered the council to allow accredited journalists to attend half an hour before the meeting was due to start. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1507044011187-4d3c340a-bdf9-4″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Contributors include Madeleine Thien, Xinran, Peter Bazalgette, Laura Silvia Battaglia, Mahesh Rao, Chawki Amari and Amie Ferris-Rotman”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special report: Free to air “][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In focus”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/magazine”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Celebrating our right to read.

A coalition of UK-based organisations will host a variety of panels, events and discussions this month to explore the freedom to read as part of the internationally-celebrated Banned Books Week.

Beginning with a workshop on 16 September hosted by Spread the Word and Islington Libraries and running until 30 September, the goal is to raise awareness about the many ways literature and ideas are censored – and celebrate our freedom to read.

“Censorship isn’t something that happens far away. It has happened in the UK. In every library there are books that British citizens have been blocked from reading at various times. As citizens and literature lovers we must be constantly vigilant to guard against the erosion of our freedom to read,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship said.

Events include an evening of discussion with Melvyn Bragg and guests on The Satanic Verses controversy at the British Library; a discussion on the “unsayable” with cartoonist Martin Rowson; authors Patrice Lawrence and Alex Wheatle on writing for young people; and David Aaronovitch and guests exploring tactics used to censor voices around the world at Free Word.

Lisa Appignanesi, chair of the RSL, said: “It’s an irony that the list of books banned over the last centuries, whether by religious or political authorities jealous of their power, constitutes the very best of our literatures. From the Bible to Thomas Paine, Flaubert, G.B. Shaw to Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex and Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, some of the greatest of our books have been banned somewhere. Luckily humans have a way of valuing the prohibited and cherishing liberty; and this as George Orwell reminded us, ‘means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.’”

Islington Libraries has produced a list of some of the world’s best-known banned books for the occasion and is encouraging everyone to pick up a banned book.

Islington Council’s executive member for economic development, Cllr Asima Shaikh, said: “Islington – one-time home of George Orwell, Douglas Adams and Salman Rushdie himself – has a rich history of radical thought and creative expression and innovation, making it a natural fit with Banned Books Week.

“Our libraries are places which celebrate diversity of opinion and encourage new and interesting ideas. As a borough we continue to challenge censorship and encourage free speech, and we are very proud to be involved in such a great celebration.”

Celebrated works of literature that have experienced bans or censorship include Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series and John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars.

For more information, please contact Sean Gallagher, Index on Censorship, on [email protected].

Full schedule of Banned Books Week events

16 September: Research for fiction writers with Kerry Young

Presented by Spread the Word

Award-winning author, Kerry Young, is running a workshop for writers who want to research and write characters from a range of backgrounds.

22 September: Patrice Lawrence and Alex Wheatle in conversation

Presented by Archway With Words

ArchWay With Words presents a thrilling event with two of Britain’s most exciting, prize-winning writers who tell stories about young people.

24 September: How far can you go in speaking the unspeakable?

Presented by Index on Censorship and Pembroke College

What is the place of the satirist in our age of controversies? The irreverent cartoonist Martin Rowson, of The Guardian and Index on Censorship magazine, joins publisher Joanna Prior of Penguin Random House for what promises to be a coruscating conversation.

26 September: Censored: A Literary History of Subversion and Control

Presented by the British Library

Katherine Inglis and Matthew Fellion, authors of a fascinating new book on suppressed literature, explore the methods and consequences of censorship and some of the most contentious and fascinating cases.

27 September: What happens when ideas are silenced?

Presented by Index on Censorship and Free Word

Join award-winning journalist David Aaronovitch in conversation with Irish author Claire Hennessy and publisher Lynn Gaspard, as they explore what happens when ideas are silenced. With readings by Moris Farhi and Bidisha.

27 September: Censored at The Book Hive, Norwich

Presented by Index on Censorship

Join Index on Censorship magazine Deputy Editor Jemimah Steinfeld in conversation with Matthew Fellion and Katherine Inglis, authors of the new book Censored: A Literary History of Subversion and Control.

28 September: How censorship stifles debate

Presented by the Limerick City Trust

Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg will speak about how censorship stifles debate and undermines the tenets of free and democratic societies.

28 September: Standing with Salman

Presented by the British Library and the Royal Society of Literature

Nearly 20 years after Salman Rushdie was forced into hiding following the publication of The Satanic Verses, members of the Salman Rushdie Campaign Group re-unite to talk about their fight for freedom of expression.

30 September: J G Ballard’s Crash: On Page and Screen

Presented by the British Library

Revisit the shock of symphorophilia with Will Self and Chris Beckett, editor of a new edition of Crash. Their discussion is followed by a rare chance to see the uncut version of David Cronenberg’s 1996 film adaptation on the big screen.

Notes to editors

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]David Benatar, a professor of philosophy and head of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Cape Town, was one of the proponents behind the invitation to journalist Flemming Rose, the editor responsible for publishing controversial cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten in 2005, to deliver the 2016 TB Davie Memorial Lecture on academic freedom. The invitation to Rose was rescinded by the university because Rose’s appearance might provoke conflict on campus, pose security risks and might “retard rather than advance academic freedom on campus.” In a guest post, Benatar, writing here in a personal capacity, shares his thoughts on the 2017 lecture. [/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”81181″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]In 2016, the executive of the University of Cape Town in South Africa overrode its academic freedom committee’s invitation to Flemming Rose to deliver the annual TB Davie academic freedom lecture. Mr Rose was disinvited over the protestations of the then members of the academic freedom committee. The irony of preventing a speaker from delivering an academic freedom lecture seems to have been lost on the university’s leadership, with the vice-chancellor, Dr Max Price, publicly defending the decision to disinvite.

Like all campus censors, Dr Price professed his commitment to academic freedom and freedom of expression before justifying his violation of these very principles. His arguments were roundly criticised by some. Other members of the university community supported the decision he and his colleagues had taken, which is part of a broader institutional pathology that, so far as I can tell, is even more pervasive than otherwise similar pathologies at various universities in North America and Europe.

The TB Davie Memorial Lecture was established in 1959 by students at the University of Cape Town. It is named after Thomas Benjamin Davie, vice-chancellor of the university from 1948 until his death in 1955. Dr Davie vigorously defended academic freedom against the apartheid regime’s imposition of racial segregation on higher education in South Africa, a battle that was ultimately unsuccessful.

A preface to printed versions of some past lectures in the series says that the “TB Davie Memorial Lecture keeps before the university a reminder of its ethical duty to defend and to seek to extend academic freedom”. The events of 2016 demonstrate that reminders are insufficient. One can remember the duty without fully understanding it, and one can understand it without having the courage to discharge it. Courage is needed to protect unpopular speech and speakers, not to protect orthodox views and their purveyors.

There have been some developments to this sad saga. First the good news: The South African Institute of Race Relations, upon hearing of the disinvitation of Mr Rose, invited him to South Africa to deliver the annual Hoernle lecture, which he did without incident in both Johannesburg and Cape Town in May 2017. While in South Africa, Mr Rose also spoke at the University of Cape Town, albeit unannounced and in a small class at the invitation of a single professor. There he addressed and had a pleasant and respectful exchange with the students.

The bad news is that the academic freedom committee’s term of office ended soon after Mr Rose was disinvited. The committee’s expression of outrage over the disinvitation was its final act. There is some reason to think that this committee’s stand on the Flemming Rose matter galvanised the dominant regressive sector of the university in a way that influenced how the committee was repopulated for the new term of office.

The result is an academic freedom committee that, on the whole, is significantly tamed. For example, the new members of the committee include somebody who had criticised the earlier invitation to Mr. Rose and someone else who had claimed that “human dignity and civility trumps” freedom of speech. It is thus a committee that is much less likely to highlight or object to the many threats to academic freedom and freedom of expression within the university. It is also a committee that is unlikely to test the university’s commitment to these values by, for example, its choice of speakers for future TB Davie lectures.

It was unsurprising that the new committee has shown no signs of endorsing the six separate nominations it received for Mr Rose to deliver the 2018 lecture. Nor is it surprising that it invited Professor Mahmood Mamdani to deliver the 2017 lecture. (Although Professor Mamdani, now at Columbia University, but at one stage a professor at the University of Cape Town, has had his disagreements with the University of Cape Town, his criticisms are the staples of the university’s self-flagellation and thus very far from a test of freedom of expression.)

I wrote to Professor Mamdani on 2 April 2017 to advise him of the events of 2016 and to ask him to refuse to give this lecture until such time as Mr Rose is permitted to give his. In my email, I acknowledged that he, Professor Mamdani, “might use the opportunity of the TB Davie lecture to criticise the university for having disinvited Mr Rose”, but that it would be far more effective if he refused to give the lecture. I said that until “Mr Rose’s disinvitation is reversed, the TB Davie lecture will be a farce”.

About a dozen other members of the university community, mainly academic staff, subsequently wrote to him to endorse my request. To the best of my knowledge, none of us have received a response, and the lecture is scheduled to take place on 22 August. Until Professor Mamdani gives his lecture, we cannot be sure what he will say. However, his failure either to withdraw from the lecture or to reassure those who had written to him that he would be taking a stand against the disinvitation of Mr Rose does not augur well.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ show_filter=”yes” element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502096677412-aee0a1d7-4cdb-4″ taxonomies=”4524, 8562″ filter_source=”category”][/vc_column][/vc_row]