4 Apr 2018 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 47.01 Spring 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Omar Mohammed, Mahvash Sabet, Simon Callow and Lucy Worsley, as well as interviews with Neil Oliver, Barry Humphries and Abbad Yahya”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends.

In this issue, we examine the various ways and areas where historical narratives are being changed, including a Q&A with Chinese and Japanese people on what they were taught about the Nanjing massacre at school; the historian known as Mosul Eye gives a special insight into his struggle documenting what Isis were trying to destroy; and Raymond Joseph takes a look at how South Africa’s government is erasing those who fought against apartheid.

The issue features interviews with historians Margaret MacMillan and Neil Oliver, and a piece addressing who really had free speech in the Tudor Court from Lucy Worsley.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”99222″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

We also take a look at how victims of the Franco regime in Spain may finally be put to rest in Silvia Nortes’ article; Irene Caselli explores how a new law in Colombia making history compulsory in school will be implemented after decades of conflict; and Andrei Aliaksandrau explains how Ukraine and Belarus approach their Soviet past.

The special report includes articles discussing how Turkey is discussing – or not – the Armenian genocide, while Poland passes a law to make talking about the Holocaust in certain ways illegal.

Outside the special report, Barry Humphries aka Dame Edna talks about his new show featuring banned music from the Weimar Republic and comedian Mark Thomas discusses breaking taboos with theatre in a Palestinian refugee camp.

Finally, we have an exclusive short story by author Christie Watson; an extract from Palestinian author Abbad Yahya’s latest book; and a poem from award-winning poet Mahvash Sabet.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special report: The abuse of history “][vc_column_text]

A date (not) to forget, by Louisa Lim: The author on why her book about Tiananmen would be well-nigh impossible to research today

Who controls the past controls the future…, by Sally Gimson: Fall in line or be in the firing line is the message historian are receiving from governments around the world

Another country, by Luka Ostojić: One hundred years after the creation of Yugoslavia, there are few signs it ever existed in Croatia. Why?

No comfort in the truth, by Annemarie Luck: It’s the episode of history Japan would rather forget. Instead comfort women are back in the news

Unleashing the past, by Kaya Genç: Freedom to publish on the World War I massacre of Turkish Armenians is fragile and threatened

Stripsearch, by Martin Rowson: Mister History is here to teach you what really happened

Tracing a not too dissident past, by Irene Caselli: As Cubans prepare for a post-Castro era, a digital museum explores the nation’s rebellious history

Lessons in bias, by Margaret MacMillan, Neil Oliver, Lucy Worsley, Charles van Onselen, Ed Keazor: Leading historians and presenters discuss the black holes of the historical universe

Projecting Poland and its past, by Konstanty Gebert: Poland wants you to talk about the “Polocaust”

Battle lines, by Hannah Leung and Matthew Hernon: One battle, two countries and a whole lot of opinions. We talk to people in China and Japan about what they learnt at school about the Nanjing massacre

The empire strikes back, by Andrei Aliaksandrau: Ukraine and Belarus approach their former Soviet status in opposite ways. Plus Stephen Komarnyckyj on why Ukraine needs to not cherry-pick its past

Staging dissent, by Simon Callow: When a British prime minister was not amused by satire, theatre censorship followed. We revisit plays that riled him, 50 years after the abolition of the state censor

Eye of the storm, by Omar Mohammed: The historian known as Mosul Eye on documenting what Isis were trying to destroy

Desert defenders, by Lucia He: An 1870s battle in Argentina saw the murder of thousands of its indigenous people. But that history is being glossed over by the current government

Buried treasures, by David Anderson: Britain’s historians are struggling to access essential archives. Is this down to government inefficiency or something more sinister?

Masters of none, by Bernt Hagtvet: Post-war Germany sets an example of how history can be “mastered”. Poland and Hungary could learn from it

Naming history’s forgotten fighters, by Raymond Joseph: South Africa’s government is setting out to forget some of the alliance who fought against apartheid. Some of them remain in prison

Colombia’s new history test, by Irene Caselli: A new law is making history compulsory in Colombia’s schools. But with most people affected by decades of conflict, will this topic be too hot to handle?

Breaking from the chains of the past, by Audra Diptee: Recounting Caribbean history accurately is hard when many of the documents have been destroyed

Rebels show royal streak, by Layli Foroudi: Some of the Iranian protesters at recent demonstrations held up photos of the former shah. Why?

Checking the history bubble, by Mark Frary: Historians will have to use social media as an essential tool in future research. How will they decide if its information is unreliable or wrong?

Franco’s ghosts, by Silvia Nortes: Many bodies of those killed under Franco’s regime have yet to be recovered and buried. A new movement is making more information public about the period

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: If we don’t support those whose views we dislike as much as those whose views we do, we risk losing free speech for all

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In focus”][vc_column_text]

How gags can remove gags, by Tracey Bagshaw: Comedian Mark Thomas discusses the taboos about stand-up he encountered in a refugee camp in Palestine

Behind our silence, by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Refugees feel that they are not allowed to give their views in public in case they upset their new nation, they tell our interviewer

Something wicked this way comes, by Abigail Frymann Rouch: They were banned by the Nazis and now they’re back. An interview with Barry Humphries on his forthcoming Weimar Republic cabaret

Fake news: the global silencer, by Caroline Lees: The term has become a useful weapon in the dictator’s toolkit against the media. Just look at the Philippines

The muzzled truth, by Michael Vatikiotis: The media in south-east Asia face threats from many different angles. It’s hard to report openly, though some try against the odds

Carving out a space for free speech, by Kirsten Han: As journalists in Singapore avoid controversial topics, a new site launches to tackle these

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Just hurting, not speaking, by Christie Watson: Rachael Jolley interviews the author about her forthcoming book, why old people are today’s silent community and introduces a short story written exclusively for the magazine

Ban and backlash create a bestseller, by Abbad Yahya: The bestselling Palestinian author talks to Jemimah Steinfeld about why a joke on Yasser Arafat put his life at risk. Also an extract from his latest book, translated into English for the first time

Ultimate escapism, by Mahvesh Sabet: The award-winning poet speaks to Layli Foroudi about fighting adversity in prison. Plus, a poem of Sabet’s published in English for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

Index around the world, by Danyaal Yasin: Research from Mapping Media Freedom details threats against journalists across Europe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Frightening state, by Jemimah Steinfeld: States are increasing the use of kidnapping to frighten journalists into not reporting stories

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Abuse of History” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F%20|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends

With: Simon Callow, Louisa Lim, Omar Mohammed [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99222″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Jan 2018 | News and features, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

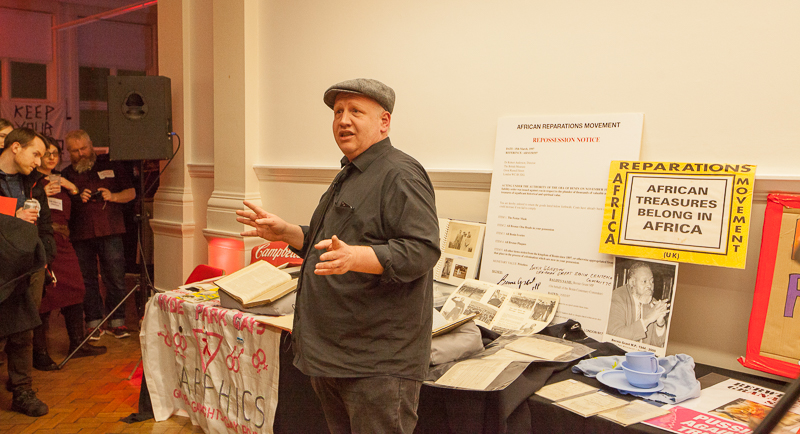

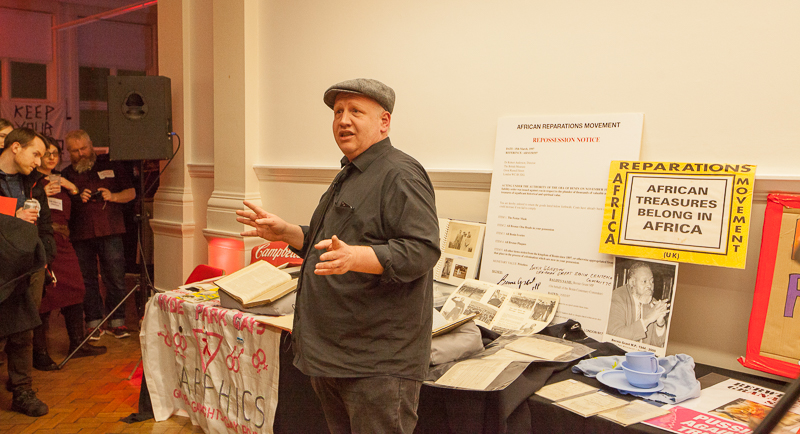

Peter Tatchell discusses the importance of the right to protest. (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Index on Censorship magazine celebrated the launch of its winter 2017 magazine at the Bishopsgate Institute in London with an evening exploring the legacies of iconic protests from 1918 and 1968 to the modern day and reflecting on how today, more than ever, our right to protest is under threat.

Speakers for the evening included human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell, Bishopsgate Institute special collections and archives manager Stefan Dickers and artist Patrick Bullock.

Tatchell discussed the importance of protest for any democracy and the significant anniversaries of protests in 2018 throughout his speech. “This year is a very special year, a very historic year, I think that those protests remind us that protest is vital to democracy,” he said. “It is a litmus test of democracy, it is a litmus of a healthy democracy. Democracies that don’t have protest, there is a problem, in fact, you might even say they aren’t true democracies.”

“With 1968 came the birth of the women’s liberation movement, the mass protests in Czechoslovakia against Russian occupation, and, of course, the huge protests against the American war in Vietnam,” Tatchell added. “Those protests all remind us that protest is vital to democracy.”

Bishopsgate Institute special collections and archives manager Stefan Dickers at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

This year also marks the centenary of the right to vote for women in Britain. Dickers showcased artefacts the Bishopsgate Institute’s collection of protest memorabilia, including sashes worn by the Suffragettes and tea sets women were given upon leaving prison for activities related to their activism.

Suffragette sashes at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Attendees included actor Simon Callow, who stressed the importance of protest and freedom of expression: in an interview at the event with Index on Censorship. “There are all sorts of things that people find inconvenient and uncomfortable to themselves, that they don’t wish to hear, but that’s not the point,” he said. “The point is that if some people feel very strongly that certain things are wrong, then they must be allowed to say something.”

Disobedient objects at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Eastenders actress Ann Mitchell, who also attended the event, said: “There is no question in my opinion, that the darkness in the world at the moment must be protested against. All the advantages we have won as women, as ethnic minorities, are being destroyed, they are being wiped out. Unless we hear voices of protests for that, that will continue.”

The night concluded with a performance by protest choir Raised Voices.

Index magazine’s winter issue on the right to protest features articles from Argentina, England, Turkey, the USA and Belarus. Activist Micah White proposes a novel way for protest to remain relevant. Author and journalist Robert McCrum revisits the Prague Spring to ask whether it is still remembered. Award-winning author Ariel Dorfman’s new short story — Shakespeare, Cervantes and spies — has it all. Anuradha Roy writes that tired of being harassed and treated as second-class citizens, Indian women are taking to the streets.b

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?”][vc_column_text]Through features, interviews and illustrations, the winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the state of protest today, 50 years after 1968, and exposes how it is currently under threat.

With: Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy, Micah White, Richard Ratcliffe[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Jan 2018 | Argentina, Global Journalist, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published 52 interviews with exiled journalists from 31 different countries.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”97517″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]It was a story that shook Argentine politics. For the journalist who broke the news, it upended his life.

On January 18, 2015, Argentine prosecutor Alberto Nisman was found dead of a gunshot wound in his apartment just days after releasing a 289-page report accusing then president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and her foreign minister of covering up Iran’s involvement in the 1994 bombing of Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA), a Jewish community center. The explosion killed 85 people and was the deadliest terrorist attack in the country’s history.

The journalist who broke the story of Nisman’s death on Twitter was Damian Pachter, a young Argentine-Israeli reporter for the English-language Buenos Aires Herald.

“Prosecutor Alberto Nisman was found in the bathroom of his house at Puerto Madero. He was not breathing. The doctors are there,” Pachter wrote.

That tweet set off a chain of events that led both to an investigation of Kirchner and to Pachter fleeing Argentina for Israel.

Kirchner’s government, which had been seeking to undermine Nisman’s allegations, immediately labeled his death a suicide, as Nisman’s body had been discovered with a handgun nearby. “What led a person to make the terrible decision to take his own life?” she wrote on Facebook, soon afterwards.

Nisman’s death and Kirchner’s move to call it a suicide triggered a massive protest in Buenos Aires. The Argentine government was later forced back away from its claims that Nisman had committed suicide, and Kirchner’s Front for Victory narrowly lost presidential elections later that year. An investigation into Nisman’s death concluded earlier this year that it was a homicide.

Pachter, who had been working on a freelance story for an Israeli newspaper about Nisman’s investigation of the bombing and the government’s efforts cover up Iran’s role, was soon targeted by the government.

Six days after Nisman’s body was found, he fled to Israel with nothing but a backpack.

Pachter, 33, now works as a producer for Israel’s i24 News and as a host for Ñews24 in Tel Aviv. As for Kirchner, she has consistently denied any role in Nisman’s death or covering up Iran’s role in the AMIA bombing. In October, she won election to the Argentine senate, a position that gives her legal immunity from prosecutor’s efforts to charge her with treason and covering up the government’s role in Nisman’s death.

Pachter spoke with Global Journalist’s Maria F. Callejon about the strange days after Nisman’s death and his flight from Argentina. Below, an edited version of their conversation, translated from Spanish:

Global Journalist: Tell us about the night of Nisman’s death.

Pachter: I was in the living room when I received the news of Nisman’s death from a source at approximately 11 p.m. For 35 minutes I talked to my source to try to verify it. At 11:35 p.m. I sent the first tweet: “I have been informed of an incident at Prosecutor Nisman’s house.”

I already knew what had happened, but I took the time to talk to my source, to check there were no mistakes and to get as much detail as I could. At 12:08 a.m. I tweeted: “Prosecutor Alberto Nisman was found in his bathroom at his house in Puerto Madero. He wasn’t breathing. The doctors are there.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”97522″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://twitter.com/damianpachter/status/557011746855321600″][vc_column_text]GJ: What were your first thoughts after receiving the information?

Pachter: I was very robotic. Immediately, I started fact-checking. Pretty much like a machine: at first, it was shocking, but I was the one who got it and I had to make sure that everything was true to then publish it. That was it. I thought I was going to be fired for tweeting first. But I told myself that if I was going to be fired for something, it might as well be this, but I had to publish it.

GJ: Did you think the government would try to cover up the incident?

Pachter: I can’t say that I didn’t, but I didn’t imagine anything precise. Knowing the government and how they treated journalists critical of them, I thought that they would create a media campaign against me. I had delivered news that affected their power, I had to have the [courage] to endure what came after. It’s part of the job. I got into journalism for this kind of thing. There are ups and downs, but you have to do your job and that is to publish what they want to hide. The investigation of Nisman’s death took two years and a new government. The previous government almost shut it down. A couple months ago, the police determined it was a homicide. Think about what would’ve happened if nobody had said anything.

GJ: What happened the day after you reported this?

Pachter: We were all in shock, nobody could believe what was happening. There was an atmosphere of fear. I interpreted that as the government making a show of their power. They had ordered the killing of the prosecutor that had accused them, and I think they didn’t consider the consequences. They didn’t think that this would be important nor that it would have the popular response it had.

GJ: How was the rest of the week?

Pachter: People were calling me, I swear, they wouldn’t stop calling from all over the world. We started doing some appearances on some big networks like CNN. In the meantime, I tried to do my job as normally as I could, but the emotion was so overwhelming, that didn’t work. I had too much adrenaline. In the days afterwards, a source of mine started messaging me to come visit. That source lived out of the city, so I didn’t pay too much attention. In the meantime, I was preparing to face further attacks from the government. I knew I was going to be targeted for being Israeli and Jewish. So I thought I would go on TV and set the record straight. I knew that they would attack me for that. I was used to the government. Any journalists that confronted them would suffer the consequences.

GJ: Were you attacked for being Jewish?

Pachter: They will do anything to discredit you. Instead of saying that I was a journalist doing my job, they said that I was working for the Israeli intelligence services, that I was an undercover agent. The government took pictures from my Facebook account of me in the Israeli army, something that I’d already talked about publicly. They marked my face with a yellow circle and sent it to pro-government groups. While this was happening, my source kept insisting that I visit. On Thursday [five days after Nisman’s body was discovered], I got an email from a colleague. The link in the mail showed that Télam, Argentina’s government news agency, had published some information about me. My name was misspelled, my workplace was incorrect and they had changed my tweets [about Nisman’s death]. This disturbed me and I thought something was going on. I sent that information to my source, who again said I should come visit. That’s when it hit me, after four days. My source was saying too that something was going on.

GJ: What did you do then?

Pachter: I left the newsroom and left my car parked there. I took a taxi back to my apartment. There, I packed a backpack with clothes for three days. That was my plan, to go and hide for three days until it all calmed down. For whatever reason, I grabbed my Israeli passport and my identity card. Then I took a bus out of town to meet with my source. While I was waiting at the cafe of a gas station, I realized a man had come into the cafe and there was something strange about him, his body language and his presence. I sat still in my seat. Time passed and this man was still there, not asking for anything to drink or eat. My source called me and told me to stay wait for him. Twenty minutes later, he was there. He came in through the back door, so he saw the man sitting behind me. My source approached me and said: “Don’t turn around. You have an intelligence officer behind you. Look at my camera and smile.” We pretended as if he were taking my picture, but he really took one of the man. When he realized what we were doing, he left. Right then I knew I had nothing else to do in the country. I was leaving. I was sure they were going to kill me, taking into account what happened to Nisman.

GJ: How did you plan your trip?

Pachter: At the cafe I did what I could to book a flight as soon as possible. The soonest one was with Argentina Airlines, from Buenos Aires to Montevideo to Madrid to Tel Aviv. I went straight to the airport to catch my flight on Saturday [six days after Nisman’s body was found]. I met my mom and said goodbye. I told her what was happening and she understood what was at stake. I also met with two colleagues of mine who were there to document it all. And then I left. During my flight, the Pink House [Argentina’s presidential residence and office] published on its official Twitter account the details of my flight. There it was clearly, just what I had thought: this was official persecution.

GJ: How did you feel when you got to Israel?

Pachter: Some friends and journalists from international media and local media met me there. Once I was there, it felt like a weight off my back. Once we landed, I felt safe.

GJ: Since you went into exile, Kirchner’s government lost the election and she was replaced by opposition candidate Mauricio Macri. Have you considered going back?

Pachter: For now, I don’t want to go back, as much as people tell me everything is fine. I have many feelings that discourage me from going. I was expelled, in a way, from Argentina. I was forced to go into exile because of my job.

GJ: Was it worth it?

Pachter: Yes, of course. I would do it a thousand times.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/tOxGaGKy6fo”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Jan 2018 | Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico, News and features, Venezuela

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Latin America is home to a growing number of independent publications, like Venezuela’s Efecto Cocuyo, that do not depend on government advertising

With general elections scheduled in six Latin American countries this year, and another six to follow in 2019, the relationship between the media and democracy could have a major impact on the future of the region. However, mounting financial pressures are robbing many media outlets of their objectivity and forcing them to toe pro-government lines.

With traditional advertising revenue in decline, Latin American governments are using vast publicity budgets to keep cash-strapped publications afloat. In return, the media are expected to portray their benefactors in a favourable light.

According to the NGO Freedom House, much of the media in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras and Mexico is heavily dependent on government advertising, resulting in widespread self-censorship and collusion between public officials, media owners and journalists.

“The history of journalism in Latin America is a history of collusion between the press and powerful people,” said Rosental Alves, a Brazilian journalist and founder of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, in an interview with Index. Sections of the media have become subservient, he explained, as any critical coverage could be punished with audits or a loss of advertising revenue.

Financial pressures on the media are particularly pronounced in Venezuela. Alves observed that the Nicolás Maduro regime has applied “waves of censorship” to the media by first decrying it as “the enemy of the people” and then buying up media companies to “make them friendly.”

Freedom House notes that “although privately owned newspapers and broadcasters operate alongside state outlets, the overall balance has shifted considerably toward government-aligned voices in recent years. The government officially controls 13 television networks, dozens of radio outlets, a news agency, eight newspapers, and a magazine.”

This is compounded by Venezuela’s severe economic problems and the virtual government monopoly on newsprint supplies that have led to newspaper closures, staff cutbacks and reduced circulation of critical media.

Mexico’s government has taken the more subtle approach of co-opting swathes of the media through unprecedented expenditure on advertising. According to the transparency group Fundar, President Enrique Peña Nieto has spent almost £1.5 billion on advertising in the past five years, more than any president in Mexican history. On top of that, state and municipal administrations have also spent millions on publicity in local media.

Darwin Franco, a freelance journalist in Guadalajara, told Index that government spending has led to some publications telling reporters “who they can and cannot criticise in their work.”

Then there is the infamous chayote, a local term for bribes paid to journalists in return for favourable coverage. Franco said Mexican reporters are particularly vulnerable to economic pressures or under-the-table incentives because it’s so hard for them to make a living.

“Freelance journalists in Mexico don’t receive the benefits that employees are legally entitled to,” he said. “National media outlets — and even some international ones — pay us minimal fees for stories, which in some cases don’t even cover the costs of reporting.”

Franco, who also teaches journalism at a local university, added that many reporters take on second jobs to supplement their income. With Mexican journalists making less than £450 per month on average, he acknowledged that “there may be people who are tempted” to take money from the government.

Despite these financial pressures, Alves is encouraged by the technology-driven democratisation of the media across Latin America, with increased internet penetration and the affordability of smartphones allowing people who could not afford computers to access nontraditional media for the first time.

These include rudimentary blogs, social media accounts and more sophisticated media startups, Alves said, with countries like Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and even Venezuela home to a growing number of independent publications that do not depend on government advertising.

“We are living a time of the decline of advertisements as the main source of revenue for news organisations. On the one hand you have this huge decline in traditional advertising because of Google and Facebook getting all this money, and on the other hand you see the virtual disappearance of the entry barriers for becoming a media outlet,” Alves noted.

“We’re moving from the mass media to a mass of media because there’s this proliferation of media outlets that don’t depend on a lot of money,” he added. “If you can gather some philanthropic support or membership, or you’re just doing it by yourself, like many courageous bloggers are doing in many parts of the region, you don’t make any money but you don’t spend any money either.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Survey: How free is our press?” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fsurvey-free-press%2F|title:Take%20our%20survey||”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-pencil-square-o” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

This survey aims to take a snapshot of how financial pressures are affecting news reporting. The openMedia project will use this information to analyse how money shapes what gets reported – and what doesn’t – and to advocate for better protections and freedoms for journalists who have important stories to tell.

More information[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”97191″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/01/tracey-bagshaw-compromise-compromising-news/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Commercial interference pressures on the UK’s regional papers are growing. Some worry that jeopardises their independence.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”81193″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/jean-paul-marthoz-commercial-interference-european-media/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Commercial pressures on the media? Anti-establishment critics have a ready-made answer: of course, journalists are hostage to the whims of corporate owners, advertisers and sponsors. Of course, they cannot independently cover issues which these powers consider “inconvenient”.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96949″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.opendemocracy.net/openmedia/mary-fitzgerald/welcome-to-openmedia”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Forget fake news. Money can distort media far more disturbingly – through advertorials, and through buying silence. Here’s what we’re going to do about it.

This article is also available in Dutch | French | German | Hungarian | Italian |

Serbian | Spanish| Russian[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1515148254502-253f3767-99a5-8″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]