9 Feb 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

To highlight the most pressing concerns for press freedom in Europe in 2017, members Index’s outgoing youth board review the year gone by with some of our Mapping Media Freedom correspondents.

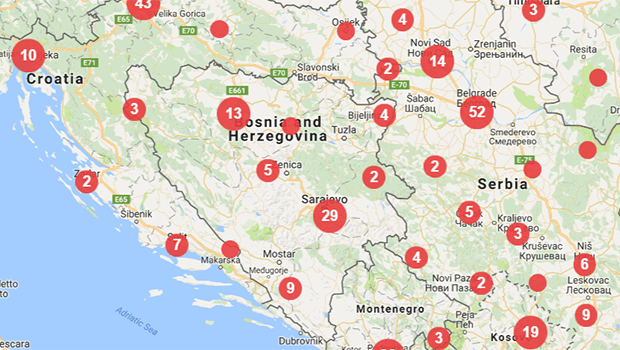

Youth board member Sophia Smith Galer, from the UK, spoke to Ilcho Cvetanoski, Mapping Media Freedom correspondent for Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Macedonia.

According to Cvetanoski, a lot has improved in the region over the last 15 years. The era during which journalists were targeted and killed is long passed, but the media is still dogged by censorship and political divides. In fact, journalists are regularly threatened and vilified by political elites, often denounced as foreign mercenaries, spies and traitors. Cvetanoski reports that this has led to “physical threats, the atmosphere of impunity, media ownership and also verbal attacks amongst the journalists themselves”. He notes that techniques pressuring journalists have changed from “blatant physical assaults to more subtle ones”.

According to Cvetanoski, a lot has improved in the region over the last 15 years. The era during which journalists were targeted and killed is long passed, but the media is still dogged by censorship and political divides. In fact, journalists are regularly threatened and vilified by political elites, often denounced as foreign mercenaries, spies and traitors. Cvetanoski reports that this has led to “physical threats, the atmosphere of impunity, media ownership and also verbal attacks amongst the journalists themselves”. He notes that techniques pressuring journalists have changed from “blatant physical assaults to more subtle ones”.

The breaking up of the former Yugoslavia has undoubtedly been a historical burden on Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. Cvetanoski describes this legacy as having left “deep scars in every aspect of the people’s lives, including the lives and the work of journalists”. Media workers are still remembered as having once been tools of the state. Nowadays, the opposite is happening; they’re being criticised by political elites as enemies of the state simply for scrutinising politicians’ behaviour.

It’s unsurprising that this has left many journalists in the region politicised, undermining professionalism and trust in the media. Conservative politicians court sympathisers in the media so that they can manipulate the angle and content of stories that are run. The fact that journalist salaries are low and that the economic situation is poor overall further imperils journalistic integrity in the face of bribes.

If the situation remains as it is – with limited and highly controlled sources for financing the media, a poor political culture and low media literacy among citizens – then Cvetanoski holds little hope for the future of press freedom in the region. News consumers aren’t equipped with the literacy levels to distinguish between professional versus sensational journalism, nor are the sources of media funding transparent or appropriate. “In this deadlock democracy, the first victims are the citizens who lack quality information to make decisions.”

Mapping Media Freedom is helping to change this. Making journalists feel less alone and offering a space for them to report threats to press freedom ensures that the hope for a free press throughout Europe is kept alive.

The youth board’s Constantin Eckner, from Germany, spoke with Zoltán Sipos, the MMF correspondent for Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria.

As MMF illustrates, journalists in all three countries have to deal with constant pressure from authorities and various degrees of censorship. In 2016, 42 incidents were reported in Hungary, 21 in Romania and 7 in Bulgaria.

As MMF illustrates, journalists in all three countries have to deal with constant pressure from authorities and various degrees of censorship. In 2016, 42 incidents were reported in Hungary, 21 in Romania and 7 in Bulgaria.

Index on Censorship’s regional correspondent Zoltán Sipos, who is also the founder and editor of Romania’s investigative outlet Átlátszó Erdély, points out that the Hungarian government and its allies within the country follow a sophisticated plan to neutralise critical media outlets. Several newspapers that struggled financially have been purchased by rich business people or media moguls in recent history. “Just like in regards to any other part of society, prime minister Viktor Orbán seeks for a centralisation of the media industry,” Sipos says.

Yet, instead of simply controlling the media, Orbán and the reigning party Fidesz intend to use established outlets and broadcasters to construct narratives in favour of their agendas. Only a handful of independent outlets remain in Hungary.

In November 2016, Class FM, Hungary’s most popular commercial radio channel, was taken off the air. The Media Council of Hungaryʼs National Media refused to renew its licence as Class FM was owned by Hungarian oligarch Lajos Simicska, whose outlets became very critical towards the government after a quarrel between him and Orbán.

The authorities in Romania and Bulgaria might not follow a well-wrought plan, but the situation for critical journalists is as severe. “The main problem is that most outlets can’t generate enough revenue from the market,” Sipos explains. “These outlets found themselves under constant pressure, as powerful business people are willing to purchase them and use them to promote their own political agendas.” Ultimately, this issue leads to the demise of independent reporting and weakens voices critical of the ruling parties and influential political players.

Sipos concludes that “these three countries have little to no tradition of independent journalism.” Although death threats towards, or even violence against journalists do not exist, the working conditions for critical reporters are difficult.

He recommends the investigative outlets Bivol.bg from Bulgaria, atlatszo.hu and Direkt36.hu from Hungary as well as RISE Project and Casa Jurnalistului from Romania as bastions of independent journalism. A few mainstream outlets that conduct critical reporting are 444.hu, index.hu, HotNews.ro and Digi24.

Layli Foroudi, a youth board member from the UK, interviewed Mitra Nazar, MMF correspondent for Serbia, Kosovo, Slovenia and the Netherlands.

A Dutch national based in Belgrade, Serbia and the Netherlands are Nazar’s natural beats, and she also monitors media freedom in the nearby Balkan states of Slovenia and Kosovo.

A Dutch national based in Belgrade, Serbia and the Netherlands are Nazar’s natural beats, and she also monitors media freedom in the nearby Balkan states of Slovenia and Kosovo.

This year, Serbia has been the most intense of the four countries to cover. Serbian journalists have been subject to physical attacks and the government has maintained a smear campaign against independent media outlets in the country.

“This is a very organised campaign,” explains Nazar, “they’re being called foreign spies and foreign mercenaries.”

The “foreign spy” accusation has a real effect on the personal safety of journalists, whose pictures are often published alongside such accusations in the pro-government media. Nazar, who wrote a feature on the subject, says that this can cause such journalists to be branded as unpatriotic and anti-Serbian: “When the government accuses journalists of being “foreign spies”, it gives the impression that these independent journalists are against Serbia as a country.”

The ruling party of Serbia even went so far as to organise a touring exhibition called Uncensored Lies, where the work of independent media was parodied in an attempt to prove that the government does not censor, however, the exhibition also served to discredit these publications by calling the content “lies”.

“Can you imagine the ruling party organises an exhibition discrediting independent media,” says Nazar, shocked, “this is not indirect censorship, it is directly from the government.”

The media landscape in the Netherlands does not experience direct state-sponsored censorship, but there are other challenges. The Netherlands ranks 2nd in the 2016 RSF World Press Freedom Index, but Nazar has still reported a total of 49 incidents since the Mapping Media Freedom project started, from police aggression against journalists, to assaults on reporters during demonstrations, to broadcasters being denied access to public meetings.

For 2017, she is interested in looking into how the Dutch media deals with the rise of the far right and a growing anti-immigrant sentiment, especially in the upcoming elections which will see controversial far-right candidate Geert Wilders stand for office.

Last year, a Dutch tabloid De Telegraaf published an article about the arrival of refugees to the Netherlands with a sensational headline that generated a lot of debate in the Dutch media, which Nazar says is becoming increasingly politicised and polarised.

For Nazar, there is a line to be drawn with what legacy media outlets should and should not publish. “That line is representing and following the facts,” she says, “if you publish a headline that says there is a “migrant plague”, that is beyond facts – it is a political agenda.”

The youth board’s Ian Morse, from the USA, interviewed Vitalii Atanasov, the MMF correspondent for Ukraine.

In just the past two months in Ukraine, journalists have been assaulted, TV stations have been banned and governments on both sides of the country’s conflict with Russia have sought to limit public information and attack those who publicise.

Vitalii Atanasov is the correspondent who reported these incidents to the Mapping Media Freedom project. Drawing on sources from individual journalists to large NGOs, Atanasov monitors violations of media plurality and freedom in Ukraine for the project. To verify a story, he sometimes contacts media professionals directly, or crowdsources through social media, as he finds that all journalists publicise cases of violation of their rights, attacks, and incidents of violence.

“Some cases are complicated, and the information about them is very contradictory,” Atanasov tells Index. “So I’m trying to trace the background of the conflict that led to the violation of freedom of expression and media.”

Many of the violations that occur in Ukraine are either individual attacks on media workers by separatists in the east or Ukrainian officials attempting to control the media through regulation and licensing.

Of about a dozen and a half reports since he began working with MMF, Atanasov says many reports stick out, such as the “blatant” attempts of authorities to influence the work of major TV channels such as Inter and 1+1 channels. Most recently, Ukraine banned the independent Russian station Dozhd from broadcasting in Ukraine. While TV has recently been the target, problems with media freedom have come from almost everywhere.

“The sources of these threats can be very different,” Atanasov says, “for example, representatives of the authorities, the police, intelligence agencies, politicians, private businesses, third parties, criminals, and even ordinary citizens.”

Atanasov and MMF build off the work of other groups working in Ukraine, such as the Institute of Mass information, Human Rights Information Center, Detector Media, and Telekritika.ua.

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1486659943480-96bea7cd-9879-6″ taxonomies=”6514, 6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Oct 2016 | Asia and Pacific, Awards, China, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, mobile, News and features

In April 2016 the US government called China’s Great Firewall a barrier to trade. This came just months after the US criticised China for cyber spying on American companies, or what the Justice Department called the “great brain robbery”.

“Obama keeps saying that if China continues employing its hacking units to attack US companies, America will tear down the Great Firewall,” Charlie Smith, co-founder of GreatFire, the anonymous group of individuals who work towards circumventing China’s Great Firewall and winners of the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for digital activism, told Index. “Great – so tear it down, let’s go.”

But it’s not happening, Smith added.

Over on the other side of America’s political spectrum, US senator Ted Cruz has been busy over the last month trying to get the US Congress to act to “prevent the Obama administration from giving the internet” to China. Cruz failed in his mission, as on 1 October the US gave up its remaining control over the internet, with the California-based Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) no longer under the direction of the Department of Commerce.

There are now fears that the change will open the door for authoritarian governments, including China’s, to get control of the network of networks, leading to greater censorship.

In Cruz’s first letter to ICANN, kicking off his attempt to stop the move, the former presidential hopeful quoted GreatFire’s research into internet censorship in China.

“I then reached out to them and said: ‘Hey, we’re GreatFire, what more do you want to know?’” Smith said. “ICANN has a representative in Beijing and that representative sits in the Cyberspace Administration office, which is censorship central, so Cruz’s campaign was very interested in that.”

Although GreatFire would not align themselves with a political party, Smith added that if Cruz really believes what he is saying and GreatFire can help, the organisation will support him on this issue.

GreatFire’s own efforts to put a hole in China’s firewall took a new turn in July 2016 with the launch of its groundbreaking new site to test virtual private networks within the country, Circumvention Central. “Stable circumvention is a difficult thing to find in China so this new site a way for people to see what’s working and what’s not working,” Smith told Index at the time.

Speaking three months on, Smith told us that although the site works and customers are overwhelmingly pleased with the service, it isn’t making as many sales as he’d hoped it would. In August the platform sold a few dozen subscriptions but Smith was really hoping to see numbers in the hundreds by this stage.

“Maybe we’re not getting enough people to the site,” Smith said. “I guess it’s timing too; people have other subscriptions that haven’t yet expired, so they’re not ready.”

“What we have done, however, is engaged with some VPN firms like a paid consultancy service and helped them improve what they are doing,” Smith added. “It’s actually been quite revealing because we can see the volatility in the market and how one service may work really well this month and next month it will basically be useless.”

GreatFire is working closely with VPN services Hide My Ass and AnchorFree, both of whom have been introductions from Index on Censorship.

The Chinese government has taken notice of Circumvention Central, sending an email to all VPN providers listed on the site asking them not to stop operating in China but to cease working with GreatFire specifically.

One reads: “Please immediately stop working with GreatFire.org. GreatFire.org is an anti-China website as declared by the Cyberspace Administration of China. We hereby express our strong concern and request you stop working with GreatFire at the earliest time possible.”

“So there’s no real serious threat from the government there,” Smith said, adding that although Chinese authorities are constantly trying to take down or attack the site, they have been wholly unsuccessful.

GreatFire is also working on its free internet browser that allows users to access content that’s behind China’s firewall. The browser is currently available in English and Chinese, but will soon be available in traditional Chinese, Arabic, Spanish, Croatian and Persian.

“We’re currently looking for publications in those languages that are blocked so we can help provide access,” said Smith.

The main focus for the future, however, is the VPN service. “We believe we have the best circumvention tool on the market and we want to show people how it works and drive adoption.”

Also read:

Smockey: “We would like to trust the justice of our country”

Zaina Erhaim: Balancing work and family in times of war

Artist Murad Subay worries about the future for Yemen’s children

Nominations are now open for 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards. You can make yours here.

22 Aug 2016 | Bosnia, mobile, News and features

University professors, poets and artists signed an open letter in support of three media workers who were targeted with death threats and hate speech. The letter, which was published in the Sarajevo daily Oslobodjenje on 21 July, said that the journalists are “targeted just because they expressed their view which is different from the majority’s”.

“Regardless of whether one agrees or not with the above-mentioned views, instigation of death threats and public lynching through creating a modern day Bosnian Index Librorum Prohibitorum is unacceptable,” the letter said.

The cases were reported to Mapping Media Freedom over three days in July.

In the first incident, Vuk Bacanovic, a journalist for the Radio-Television of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was fired for allegedly violating the internal rules and the ethical code of the television network. In a Facebook post on his personal page he criticised a public art installation that depicted the federal entity of Republika Srpska as a mass grave and concentration camp. Bacanovic wrote that he “hates the assholes from Sarajevo” who were “talking crap” by saying the city has a multi-ethnic spirit. After articles about the post were published, Bacanovic received numerous death threats via Facebook, regional TV outlet N1 reported.

Nenad Velickovic, editor-in-chief of educational career-oriented magazine Skolegijum, was then verbally harassed and threatened as a result of three articles written by Filip Mursel Begovic, editor-in-chief of the weekly Stav, which were published in June and July. Begovic described Velickovic as a “man with a hidden and dangerous agenda”, “a falsifier” and a “Serbian nationalist” while describing the magazine Skolegijum as “extended arm of Serbian chauvinism”, Analiziraj.ba reported.

The letter was also written in support of the secretary general of BH Journalists’ Association Borka Rudic, who was subjected to verbal harassment by unidentified men after a high-ranking member of the Party of Democratic Action, an ethnic Bosniak political party, described her, amongst other things, as a “lobbyist for Fethullah Gulen”, website media.ba, reports.

The three incidents reflect the ethnic divisions and stereotypes that were re-enforced by the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia. The post-conflict society is governed through a complex political system established by the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords. The power-sharing constitution recognises each of the three major ethnic groups – Bosniaks (Muslims), Serbs (Orthodox) and Croats (Catholics) – as the constituent peoples of Bosnia. In practice, the recognition means that anyone not identified as belonging to one of the three groups could not be elected to hold a public office, despite a 2009 European Court of Human Rights ruling ordering the constitution to be revised.

Following the formula set out in the Dayton Accords, Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into two entities – the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with majority ethnic Bosniak and ethnic Croatian inhabitants, and the Republika Srpska, with majority ethnic Serbian population. Additionally there is the district of Brcko, which is separate enclave jointly administered by both.

The three groups also differ on the future of Bosnia. Some Bosniaks advocate for a more unitary state, while some Serbs want a more confederate arrangement or even dissolution of the state. At the same time there are Croats that want a separate ethnic entity. The competing visions of Bosnia’s future are heavily influenced by historic and recent incidents including charges of genocide, crimes against humanity and other atrocities that occurred during the 1992-95.

The Centre for Security Governance says that the governing structure “has discouraged inter-group cooperation and reconciliation. Political elites have pandered to ethnic fears, resulting in the electoral victories of ethnonational parties via the phenomenon of ‘ethnic outbidding’.”

Some politicians use friendly media to advocate for further strengthening of ethnic politics, while journalists and intellectuals that argue for strengthening civic identities and bridging ethnic hatred are usually vilified as traitors if they are from the same ethnic background, or enemies, if they are from another ethnicity. All of the cases addressed in the open letter originated in Bosniak nationalist media and were targeted at either another ethnicity or individuals who prefer civic above ethnic identity. Velickovic was described as a “man with a hidden and dangerous agenda” by a Bosniak journalist because he was advocating for non-nationalistic school curriculum.

“The importance of maintaining strong journalistic ethics cannot be underscored enough, especially given the country’s recent history. Members of the media profession must strive to be balanced, refrain from inflaming already tense inter-ethnic relations and guard against being used for political ends,” Hannah Machlin, project officer for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, said.

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, in an open letter also noted that the latest events open a very worrying chapter on the safety of journalists.

“People engaged in investigative reporting and expressing different opinions, even provocative ones, should play a legitimate part in a healthy debate and their voices should not be restricted,” Mijatovic said.

In the current climate, the open letter in support of and signed by people of different ethnicities is a small step forward. Signatory Asim Mujkic, a professor at the faculty of political sciences at the University of Sarajevo, said the cases were a call to action.

“My initial motive was to protest against the mainstream hegemonic ideological view that aggressively imposes itself upon independent and free-thinking intellectuals and public workers that, in the context of Bosnia and Herzegovina, usually targets vulnerable ethnicities for the purpose of its political mobilization,” Mujkic told Index on Censorship.“We need to fire back, especially in such circumstances.”

6 Jun 2016 | Croatia, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Hungary, News and features

Since the 1920s, generations of western Europeans got used to the monopoly of public radio and later public television. These broadcasters developed strategies to better serve audiences and distance themselves from governments. The arrival of private broadcasters, in many cases taking place only in the 1970’s, was generally viewed as a complimentary service aimed at entertaining the public. Although public service broadcasting lost market share, it remained a respected institution in society; necessary to bring up youth, to get an objective picture of the world and cater to the interests of minorities.

Eastern Europeans also got used to the monopoly of state radio and television. Those broadcasters served the communist parties and were administered and financed by governments. Their political bankruptcy came with the collapse of communist ideology, underlined in particular by the plurality of private broadcasters that came on to the scene in the early 1990s.

These private media – with plentiful Western programming – was indeed television, for so long hidden from the viewers by totalitarian regimes. Politicians flocked to their studios to take part in talk shows, abandoning once-mighty state television. Thus, in the east, the public perception of public broadcasting was predominantly sceptical, if not negative. A discussion on its development was of tangential interest, at least during the saturation process of the new private media.

Abandoned by politicians and the public, the slow and clumsy transformation of the state broadcasters into public ones was guided by the bureaucrats, almost by themselves. The driving force behind the transformation was almost exclusively the activity of Strasbourg and Brussels. We all know that in the words of European institutions “public service broadcasting is a vital element of democracy in Europe.” Transformation of state television into a public one was a condition precedent of new democracies becoming member states of the Council of Europe in some cases. The authenticity of the transformation has been important to become a candidate for entry into the European Union and even sometimes to NATO.

Developments in younger EU member states show the importance of public service broadcasters for the development of democracy – and how they can be misused.

In December 2015, Poland‘s parliament adopted a law giving the treasury minister the mandate to appoint and dismiss members of management and supervisory boards. Since the law came into effect in January, reportedly more than 100 journalists in public media have lost their jobs, allegedly for not being government-friendly.

In March, the Croatian parliament dismissed the director general of Croatian Radio-Television. A week later, the government also proposed that parliament reject a regular report from the independent media regulator, both events raising serious concerns about the overall media freedom situation in the country.

Hungary was probably the first example in the EU where public service broadcasting was practically turned back into state broadcasting, going against international standards calling for independence. New media laws in 2010 and the restructuring of the media landscape led, within a matter of one year, to all public service media being subordinated to political decisions. The new system introduced and cemented the political dependence of public service media; the governing party had nominated all new heads of public service media and the Media Authority now controls the budget of all public service media. The law vested unusually broad powers in the politically homogeneous Media Authority and Media Council, enabling them to control content of all media.

The battle to establish credible public service broadcasters in transitional democracies has been even more difficult to wage.

The latest example is the steering board of Bosnian Radio and Television which last month decided to suspend operation of all programming at the end of this month. This decision, a wrong one for several reasons, follows years of political and financial wrangling over control of the operation.

Throughout the western Balkans, significant issues are pending affecting the independence and financial stability of public broadcasting.

A bureaucratic response to the need to establish public service broadcasters has brought predictable results. The newly established broadcasters were visibly underfunded, with formal and informal administrative links – if not strings – to governments and no clear commitments to the public. Once established, it was unclear what to do with them. Most governments viewed them as an element of bureaucracy itself, a burden to carry on the road to a united Europe. If possible and convenient, they tried to make use of them through a carrot-and-stick policy.

As such, the new public service broadcasters immediately became subject to criticism by almost anyone who wanted to speak about them. Left to survive in the monstrous buildings of brutal architecture that once belonged to powerful state television, they had to sell airtime to advertisers, beg for Western donations and save on everything.

The advance of the internet and other new technologies almost killed the whole idea of television and radio, including public service broadcasting. It was saved by the transformation process – from public service broadcasting to public service media. In the West, the BBC and other companies have struggled to make use of the changing trends in media consumption. They went online, launched smartphone applications, became interactive, archived in order to engage fragmented audiences where and when required by the viewers.

Unfortunately this is not the case in the East. Public service broadcasters at best try to appeal to the older and well-educated audiences, traditional in their use of public service media. For our children, today’s debate is not only irrelevant, it is beyond their understanding.

Is there a future?

In my view we are losing the battle and might soon lose the war. To reverse the trend, we should do the following:

Give public service broadcasters a clear-cut mandate and obligation to program for the public which, in turn, should have effective feedback and control over content. There should be programmes that cater to minorities; there should be objective news, calm and matter-of-fact debates, educational and children’s programmes.

Public service broadcasters should function independently of the government. Buffer boards, meaning councils should be established to guarantee that only an abuse of a clear-cut mandate may serve to reprimand or dismiss an editor; only mismanagement and corruption may lead to firing executive directors.

And, finally, licence fees should be introduced or increased to heighten a feeling of public ownership. We can talk about other methods of independent funding, but none of them may bring this feeling of owning an institution that serves you.

Recent columns:

Dunja Mijatović: Chronicling infringements on internet freedom is a necessary task

Dunja Mijatović: Propaganda is ugly scar on face of modern journalism

Dunja Mijatović: There is hope that justice can be served in Serbia

According to Cvetanoski, a lot has improved in the region over the last 15 years. The era during which journalists were targeted and killed is long passed, but the media is still dogged by censorship and political divides. In fact, journalists are regularly threatened and vilified by political elites, often denounced as foreign mercenaries, spies and traitors. Cvetanoski reports that this has led to “physical threats, the atmosphere of impunity, media ownership and also verbal attacks amongst the journalists themselves”. He notes that techniques pressuring journalists have changed from “blatant physical assaults to more subtle ones”.

According to Cvetanoski, a lot has improved in the region over the last 15 years. The era during which journalists were targeted and killed is long passed, but the media is still dogged by censorship and political divides. In fact, journalists are regularly threatened and vilified by political elites, often denounced as foreign mercenaries, spies and traitors. Cvetanoski reports that this has led to “physical threats, the atmosphere of impunity, media ownership and also verbal attacks amongst the journalists themselves”. He notes that techniques pressuring journalists have changed from “blatant physical assaults to more subtle ones”. As MMF illustrates, journalists in all three countries have to deal with constant pressure from authorities and various degrees of censorship. In 2016, 42 incidents were reported in Hungary, 21 in Romania and 7 in Bulgaria.

As MMF illustrates, journalists in all three countries have to deal with constant pressure from authorities and various degrees of censorship. In 2016, 42 incidents were reported in Hungary, 21 in Romania and 7 in Bulgaria. A Dutch national based in Belgrade, Serbia and the Netherlands are Nazar’s natural beats, and she also monitors media freedom in the nearby Balkan states of Slovenia and Kosovo.

A Dutch national based in Belgrade, Serbia and the Netherlands are Nazar’s natural beats, and she also monitors media freedom in the nearby Balkan states of Slovenia and Kosovo.