Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

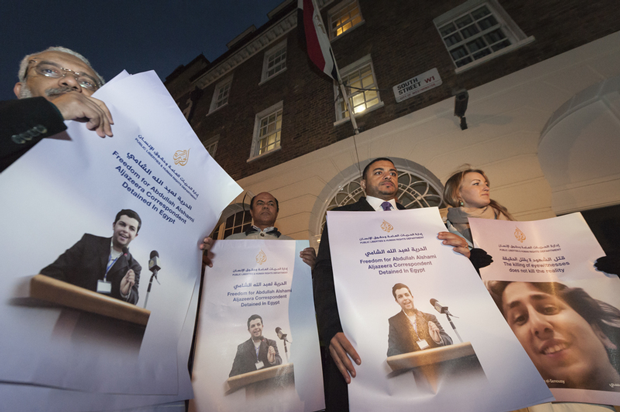

In November 2013, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ UK and Ireland), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and the Aljazeera Media Network organised a show of solidarity for the journalists who have been detained, injured or killed in Egypt. (Photo: Lee Thomas / Demotix)

Statement: Egyptian authorities must stop their attacks on media freedom from Article 19, the Committee to Project Journalists, Index on Censorship and Reporters Without Borders

Twenty journalists working for the Al Jazeera TV network will stand trial in Egypt on charges of spreading false news that harms national security and assisting or joining a terrorist cell.

Sixteen of the defendants are Egyptian nationals while four are foreigners: a Dutch national, two Britons and Australian Peter Greste, a former BBC Correspondent. The chief prosecutor’s office released a statement on Wednesday saying that several of the defendants were already in custody; the rest will be tried in absentia.The names of the defendants, however, were not revealed. The case marks the first time journalists in Egypt have faced trial on terrorism-related charges, drawing condemnation from rights groups and fueling fears of a worsening crackdown on press freedom in Egypt .

“This is an insult to the law,” said Gamal Eid, a rights lawyer and head of the Arab Network for Human Rights Information. “If there is justice in Egypt , courts would not be used to settle political scores”, he added.

In December, the government designated the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. It has since widened its heavy-handed crackdown on Brotherhood supporters, targeting pro-democracy activists, journalists and anyone considered remotely sympathetic to the outlawed Islamist group.

In a move seen by rights advocates as a blow to freedom of expression, most Islamist channels were shut down by the Egyptian authorities almost immediately after Islamist President Mohamed Morsi was toppled in July. The Qatar-based Al-Jazeera is one of the few remaining networks perceived by the authorities as sympathetic to Morsi and the Brotherhood.

Once praised by Egyptians as the “voice of the people” for its coverage before and during the 2011 mass protests that led to the removal of autocrat Hosni Mubarak from power, Al Jazeera has since seen its popularity dwindle in Egypt. Since Morsi’s ouster by military-backed protests in July, Qatar has been the target of media and popular wrath because of its backing for the Brotherhood. Allegations by the state controlled and private pro-government media that Qatar was”plotting to undermine Egypt’s stability” has inflamed public anger against the Qatar-funded network, prompting physical and verbal attacks by Egyptians on the streets on journalists suspected of working for Al Jazeera.

The Al Jazeera Arabic service and its Egyptian affiliate Mubasher Misr were the initial targets of a government crackdown on the network and have had their offices ransacked by security forces a number of times. In recent months however, the crackdown on the network has escalated, targeting journalists working for the Al Jazeera English service as well despite a general perception among Egyptians that the latter is “more balanced and fair” in its coverage of the political crisis in Egypt.

The Al Jazeera network has denied any biases on its part and has repeatedly called on Egypt to release its detained staff. According to a statement released by Al Jazeera on Wednesday, the allegations made by Egypt’s chief prosecutor against its journalists are “absurd, baseless and false.”

“This is a challenge to free speech, to the right of journalists to report on all aspects of events, and to the right of people to know what is going on.” the statement said.

Three members of an Al Jazeera English (AJE) TV crew were arrested in a December police raid on their makeshift studio in a Cairo luxury hotel and have remained in custody for a month without charge. Both Canadian-Egyptian journalist Mohamed Fahmy — the channel’s bureau chief –and producer Baher Mohamed have been kept in solitary confinement in the Scorpion high security prison reserved for suspected terrorists and dangerous criminals. An investigator in the case who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the press said Fahmy was an alleged member of a terror group and had been fabricating news to tarnish Egypt’s image abroad.

Earlier this week, Fahmy’s brother, Sherif, complained that treatment of his brother had taken a turn for the worse and that prison guards had taken away his watch, blanket and writing materials.

Peter Greste, the only non-Egyptian member of the AJE team has meanwhile, been held at Torah Prison in slightly better conditions. In a letter smuggled out of his prison cell earlier this month, Greste recounted the ordeal of his Egyptian detained colleagues, saying “Fahmy has been denied the hospital treatment he badly needs for a shoulder injury he sustained shortly before our arrest. Both men spend 24 hours a day in their mosquito-infested cells, sleeping on the floor with no books or writing materials to break the soul-destroying tedium.”

Al Jazeera Arabic correspondent Abdullah El Shamy, another defendant in the case, has meanwhile been in jail for 22 weeks. He was arrested on August 14 while covering the forced dispersal by security forces of a pro-Morsi sit-in and has been charged with inciting violence, assaulting police officers and disturbing public order. El Shamy began a hunger strike ten days ago to protest his continued detention. In a letter leaked from his cell at Torah Prison and posted on Facebook by his brother, El Shamy insisted he was innocent of all charges. He remains defiant however, saying that “nothing will break my will or dignity.” On Thursday, his detention was extended for 45 days pending further investigations . His brother Mohamed El Shamy, a photojournalist, was arrested in Cairo on Tuesday while taking photos at a pro-Muslim Brotherhood protest. He was released a few hours later.

Al Jazeera Mubashir cameraman Mohamed Badr is also behind bars. He was arrested while covering clashes between Muslim Brotherhood supporters and security forces in July and has remained in custody since.

The case of the Al Jazeera journalists sends a chilling message to journalists that there is a high price to pay for giving the Muslim Brotherhood a voice. A journalist working for a private pro-government Arabic daily sarcastly told Index that there is only one side to the story in Egypt: the government line. Mosa’ab El Shamy, a photojournalist whose brother is one of the defendants in the Al Jazeera case posted an article this week on the website Buzzfeed, humorously titled: If you want to get arrested in Egypt, work as a journalist.

In truth though, the case is no laughing matter. National Public Radio’s Cairo Correspondent Leila Fadel said it shows just how far Egypt has backslid on the goals of the January 2011 uprising when pro-democracy protesters had demanded greater freedom of expression. Today, violations against press freedoms in Egypt are the worst in decades, according to the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists. Sadly, it does not look like the situation for journalists in Egypt will improve anytime soon.

In the meantime the fate of the Al Jazeera journalists hangs in the balance.

This article was posted on 31 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Supporters of General Sisi in December 2013 (Photo: Sharron Ward / Demotix)

National Police Day, 25 January 2011. Years of police brutality is being challenged by activists in Tahrir Square. Volleys of tear gas mark the beginning of the Egyptian revolution, even if nobody knows it yet.

“The police were in control of everything that day,” journalist Muhammad Mansour remembers. “But it was a sign. I remember feeling like that day was a test for the police…it was a difficult fight.”

But three years on and Egypt looks a very different place. On Friday at least 64 people were killed nationwide – most of them with live ammunition – and 1,076 people arrested, according to official figures. Informal counts put the number of deaths closer to 100.

While revolutionary protesters were shot dead in downtown Cairo, including an April 6 activist – Sayed Wezza – who campaigned for the Tamarod movement against former Islamist President Mohamed Morsi, over 40 Muslim Brotherhood supporters were gunned down in the north-east of the capital. In both cases, authorities allegedly resorted to using near-immediate lethal force to disperse protests and, activists claim, silence dissent.

One revolutionary march from Mostafa Mahmoud square was dispersed quickly, another outside the Journalists’ Syndicate faced a similar reaction. In both cases, police reacted minutes after marches started moving. A statement from an April 6 Youth Movement organiser, texted minutes after the dispersal started, alleged the police had used live ammunition to disperse peaceful protests. “This is not the Egypt we are looking for,” it said.

“We didn’t even reach three blocks from the syndicate before we came under attack,” Revolutionary Socialist activist Tarek Shalaby says. After the tear gas started, he ran into a side-street as police vans hurtled round corners firing off tear gas and bullets. Shalaby then picked up a poster of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and got out. Not far from the clashes, Shalaby was then questioned by a Sisi supporter who was keen to know why his poster of the general was ripped.

National Police Day was once a stage-managed celebration of state authority. This year’s 25 January felt like that and more. Egyptians poured into Tahrir Square to the ubiquitous sounds of pro-army anthem ‘Teslam al-Ayadi.’ Crowds roared as military helicopters breezed over rooftops dropping Egyptian flags and vouchers for basic goods. For many, it was a stage-managed endorsement of General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s expected bid for the presidency – but one a majority of Egyptians wholeheartedly support.

While police attacked revolutionary and Brotherhood protests, the Saturday celebrations also revealed a street-level willingness to act side by side with the police.

It’s a role encouraged by state and independent media, Shalaby claims, referring to calls by Egyptian news channels for members of the public to citizen’s arrest potential Brotherhood supporters, or people looking to disrupt the day. Given Egypt’s currently hyper-nationalist state narrative, that leaves activists, Brotherhood members as well as journalists and foreigners privy to abuses.

An Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE) report recorded 36 violations against journalists and photojournalists on January 25. Vigilante justice, and impunity for those carrying it out, is a growing problem.

“I was interviewing the ‘Bride of Sisi’, as she called herself, when a crowd gathered around me and another journalist and accused us of working for a ‘terrorist’ news channel,” journalist Nadine Marroushi wrote in a London Review of Books blog. While interviewing inside the square, Marroushi and Daily News Egypt journalist Basil al-Dabh were accused of working for Al-Jazeera, insulted and physically assaulted. The police intervened and detained them for their own safety. “They took us away to a building just off the square and told us to hide there for an hour until the crowd calmed down.”

A video from a nearby street also showed a police officer telling a MBC Egypt camera camera to “move that camera…or I’ll tell the crowds you’re from Al-Jazeera.” The Qatari broadcaster has become deeply unpopular with many Egyptians, seen as one arm of the Muslim Brotherhood, itself identified as a terrorist organization in late December. Five Al-Jazeera journalists are currently in prison on charges of spreading false news and membership of a terrorist organization.

In a separate incident Matthew Stender, who went down to Tahrir to photograph the celebrations, was assaulted after running over to see where two Spanish journalists were being mobbed. Stender in turn was attacked. This time the army intervened and held him in a nearby room for an hour. While the Spanish journalists looked “quite roughed up,” Stender says, two other Egyptian journalists also accused of working for Al-Jazeera showed signs of “substantial injuries… [one] had a gash in the back of his head.”

In the run-up to January 25 this year, interim President Adly Mansour declared the “end of the police state in Egypt”. Meanwhile a damning report by Amnesty International last week condemned post-Morsi “state violence unseen even during the first 18 days of the ‘January 25 Revolution’,” expressing concerns that authorities are “utilizing all branches of the state apparatus to trample on human rights and quash dissent.” And the growing trend of violent protest dispersals, politicized detentions and home arrests suggest that Egypt is actually witnessing a return to old practices, only today they are dressed up in a fresh narrative indelibly stained red, white and black.

This article was published 0n 27 January at www.indexoncensorship.org

Thousands of Egyptians celebrated the 25th of January 2011 revolution anniversary at Al Etihadia Palace Square. Demonstrators chanted for the army and police and raised flags and banners bearing images of Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. (Photo: Adham Khorshed / Demotix)

As thousands of Egyptians demonstrated in support of the country’s military, journalists were attacked, 49 people were killed and 247 others were injured in anti-government marches across Egypt on Saturday on the third anniversary of the uprising that led to the overthrow of autocrat Hosni Mubarak.

The figures were announced by Egypt’s Health Ministry but Al Nadeem Center, a Cairo-based rights organization, gave an even higher death toll, adding that more than 1,000 people had been arrested in a day of violent clashes between protesters and security forces.

Still, a significant number of Egyptians refused to let the violence dampen their celebratory mood. Thousands of flag-bearing revellers flocked to Cairo’s iconic Tahrir Square on Saturday to rally in support of the army. Raising pictures of Defense Minister General Abdel Fattah El Sisi , they called on him to run for the presidency, chanting “El Sisi is our president” and “the people, the army and the police are one hand”.

Three years after the mass protests demanding an end to Mubarak’s police state system, the revelry and nationalistic fervour demonstrated a reversal in public sentiment towards the military and the police, which were perceived in a negative light during the transitional period that followed the ouster of Mubarak. It also underlined the bitter polarisation in the country.

“The people want the execution of the Muslim Brotherhood!”, the Tahrir crowd chanted over and over.

Security was intensified after a series of bombings rocked Cairo the previous day — the largest of them a remote-controlled car bombing targeting the security directorate near the centre of the city. At least six people were killed in the bomb attacks and scores of others were injured. Ansar Beit al Maqdis — an al Qaeda-affiliated jihadi group — claimed responsibility for the bombings. The group threatened more violence and warned people to stay off the streets. Many Egyptians dismiss the persistent denials by the Muslim Brotherhood — recently designated by Egypt’s military-backed authorities as a terrorist organization — that the Brotherhood was behind the violence. The Brotherhood insists its struggle is peaceful and has issued a statement on its official website condemning the terrorist attacks. Tens of thousands of riot police and armoured personnel carriers were deployed to try to maintain order and Tahrir Square was ringed by barbed wire to prevent pro-Muslim Brotherhood marchers entering the square.

Supporters of toppled Islamist President Mohamed Morsi staged marches in 34 Cairo neighbourhoods , protesting his overthrow. In a statement published on their website Ikhwanweb the previous day, they vowed to continue their protests until they topple “the fascist coup regime”. Security forces fired volleys of tear gas and gunshots in the air to disperse the protesters. Scores were killed or injured in ensuing clashes with riot police and pro-military residents who hurled stones and bottles at the protesters. Hundreds of demonstrators were arrested.

Pro-democracy activists meanwhile, staged a protest rally outside the Journalists Syndicate in downtown Cairo to express their opposition to authoritarian rule. “Down with military rule and down with the Muslim Brotherhood,” they chanted before being violently attacked by security forces and pro-military residents. The protesters ran for cover amid thick clouds of choking tear gas.

In the mayhem that followed, leftist activist Tarek Shalaby who was among the opposition protesters, sent a message on Twitter advising his comrades to “grab posters of El Sisi to avoid being targeted by riot police.” He also warned others to steer clear of the downtown area, describing it as “extremely dangerous.” For Sayed Elwez, a young member of the April Six group that played a key role in mobilising protesters ahead of the January 2011 uprising, the warnings were too little, too late. He was shot in the neck and chest by security forces while trying to escape. Ironically, Elwez had been among the thousands of secular volunteers in the Tamarod campaign, collecting signatures for a petition calling for Islamist President Mohamed Morsi’s resignation.

In recent weeks, the military-backed government’s brutal crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood supporters has widened, targeting dissenters of all stripes including liberal activists, journalists and prominent academics. Paradoxically, many of those targeted had previously opposed the Muslim Brotherhood president, aligning themselves with the country’s notorious security apparatus to remove him from office.

Two prominent Egyptian political scientists are the latest targets of the crackdown which rights activists say, is aimed at silencing all critics of the military-led authorities. Emad Shahin, an internationally-acclaimed and widely respected academic who has taught at Harvard and Notre Dame has been charged with “espionage and conspiring with foreign organizations to undermine Egypt’s national security”. His name has been added to a list of majority-Brotherhood defendants (which also includes the former President Mohamed Morsi) facing trial on similar charges that some rights activists believe are “politically motivated”. Shahin has denied the charges , insisting that his true offence “was criticism of the political events in Egypt since Morsi’s ouster”.

Amr Hamzawy, another political scientist and former lawmaker has meanwhile, been accused of “insulting the judiciary”. The legal complaint against him stems from a message he posted on his Twitter account in June, in which he criticized a court verdict sentencing 43 NGO workers to one to five year jail terms. The NGO staffers were accused of “working for unlicensed institutions and receiving illegal foreign funding”. Hamzawy described the verdict as “shocking and lacking in evidence and transparency”. The highly-publicised NGO case, also widely criticised by international rights activists, was seen by many as symbolising “a severe crackdown on civil society in Egypt”.

Amnesty International has criticized the widening crackdown on rights activists in Egypt, expressing concern that the Egyptian authorities were “tightening the noose on freedom of expression and assembly”. In a statement released soon after the charges were levelled against Shahin and Hamzawy, Hassiba Hadj Sahraoui, Middle East and North Africa Deputy Director at Amnesty International said “repressive legislation” was “making it easier for the government to silence its critics”. She warned that “with such measures in place” Egypt was “headed firmly down the path toward further repression and confrontation”.

Several prominent pro-democracy activists languish in jail for taking part in ”illegal protests”. Rights advocates say their imprisonment signals the return of Mubarak’s police state and that counter- revolutionary forces are back with a vengeance. In letters of despair leaked from their solitary prison cells, Ahmed Maher and Alaa Abdel Fattah (two symbols of the uprising against Mubarak) speak of a “failed revolution” that has been hijacked first by a religious group, then by the military.

In a letter to his two sisters written earlier this month, activist Alaa Abdel Fattah also wrote: “What adds to my feeling of oppression is that I feel this particular lock up has no value. This is not struggle, and there is no revolution.”

Journalists too have not been spared; in recent months they have continued to face physical assaults, intimidation and detentions. At least five journalists are currently behind bars for reporting on the ongoing political crisis. Three members of an Al Jazeera English TV crew have been in custody for nearly a month pending investigations on charges of “spreading lies harmful to Egypt’s national security and and joining a terrorist group”. In a letter recently smuggled out of his Torah prison cell, Al Jazeera correspondent Peter Greste recounts the ordeal of his two Egyptian colleagues who are being accused of belonging to a terrorist organisation and are held in a high security prison.

“Fahmy has been denied the hospital treatment he badly needs for a shoulder injury he sustained shortly before our arrest. Both he and Baher spend 24 hours a day in their mosquito-infested cells, sleeping on the floor with no books or writing materials to break the soul- destroying tedium,” Greste lamented in his note published on the Al Jazeera English website.

Several journalists covering Saturday’s pro-military Tahrir rallies meanwhile, reported coming under attack from mobs who suspected them of working for Al Jazeera. The Qatari-based network is highly unpopular in Egypt because of what many Egyptians perceive as a pro- Muslim Brotherhood bias in its coverage of the political crisis in Egypt. Meanwhile , the state-run and state-influenced media alike are awash with conspiracy theories and talk of foreign plots to divide and destroy Egypt. This has fuelled the xenophobia in Egypt, posing a serious security challenge for foreign journalists covering the protest rallies. Journalist Nadine Maroushi who was attacked in Tahrir Square on Saturday has shared her traumatic experience on her blog:

“In Tahrir Square yesterday a man suggested we worked for Al Jazeera. An angry crowd quickly formed around us. ‘You traitor, you pig,’ a veiled woman shouted at me. She pulled my hair and grabbed at my scarf, choking me. The police intervened; I showed my press pass. They took us away to a building just off the square and told us to hide there for an hour until the crowd calmed down.”

A message posted by freelance journalist Bel Trew on Twitter on Saturday also warned that Tahrir was not safe for journalists. Trew’s tweet was retweeted more than a hundred times within minutes, triggering a frenzied exchange of telephone numbers to report assault and harassment of journalists. Egyptian photojournalist Mosa’ab El Shamy, meanwhile described it as “horrible day for journalists in Cairo. At least 5 (including a foreigner) were arrested, 2 are in hospital and 7 cameras have been seized by the police and confiscated,” he tweeted.

Three years on, the revolutionary activists’ hopes for dramatic change have all but faded. With the demands for freedom of speech, equality , dignity and an end to police brutality and corruption unfulfilled, the political turmoil and instability of the past three years have forced many Egyptians to drastically lower their expectations. Forsaking their ambitions for freedom and democracy — at least for now — many in Egypt have settled instead for the lesser hope of restoring stability in the country gripped by violence. Stability can only be guaranteed with a return to military rule , they say. But not all Egyptians have given up their revolutionary dream of a free and democratic society. A small but resilient group of young activists that refuses to bow under repression is keeping the dream alive. They are the country’s hope for change. “Today was a harsh defeat on a long and bumpy road,” Tarek Shalaby wrote on Twitter, but there is no going back.

This article was posted on 27 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

An alleged supporter of ousted President Mohamed Morsi clashes with Egyptian security forces in front of Cairo University, Egypt 12th January 2014 (Image: Nameer Galal/Demotix)

Egyptians head to polling stations on Tuesday to vote on a revised constitution heralded by Egypt’s military-backed government as a” first step in the country’s democratic transition” and billed as a blueprint for the “new Egypt.”

The amended document has also been hailed by analysts as one that “enshrines personal and political rights in stronger language than in previous constitutions.” Rights advocates however, have expressed fears that the enormous powers and privileges the ‘new’ charter grants the military could undermine those rights, rendering them meaningless .

The public is being reassured that the revised charter is “a vast improvement to the 2012 Muslim Brotherhood constitution” that was scrapped when the Islamist former President Mohamed Morsi was toppled by military-backed protests in July. In an Op-Ed published in the New York Times last week, Amr Moussa, a former Foreign Minister under deposed President Hosni Mubarak and the Head of the 50-member committee that amended the 2012 Constitution, said that the document –in its new form– “meets the needs and aspirations of all Egyptians” unlike the previous charter which he said, “had been rushed through by a single dominating political faction and answered only to its priorities”.

Ads in the local media and on billboards across the country promote a ‘yes’ vote on the charter, portraying its ratification as a ‘patriotic’ act. Public service messages broadcast on radio and TV stations tell Egyptians that even if they disagree with some of its provisions, the charter is “not permanent—Egypt is.” A ‘yes” vote will “complete the unfinished revolution Egyptians began on June 30,” intones the broadcaster in reference to the day millions took to the streets demanding the downfall of the Islamist regime.

The new charter grants Egyptians greater freedom of expression and belief and ensures equality between men and women. The provision on women’s rights says the state must take necessary measures to guarantee women have proper representation in legislative councils, hold senior public and administrative posts, and are appointed to judicial institutions. It obligates the state to provide protection to women against any form of violence. Meanwhile, articles that gave the previous constitution an “Islamist flair” have either been removed or replaced by others that limit the scope of Islamic law or Shariah. The charter also reaffirms the country’s commitment to its obligations under all previously signed international treaties and agreements including human rights covenants. It also empowers lawmakers to remove the president with a two-thirds majority, obliges the president to declare his financial assets and bans political parties founded on religion, sect or region. All of the above signal victory for Egypt’s liberals and rights advocates who had been vocal in their concerns about flaws in the previous constitution including provisions on religious freedoms and other liberties and rights of women and minorities.

But skeptics caution it may be too early to rejoice.

While some analysts hail a provision banning the prosecution of journalists for ‘publication offences’ as one that will “reinforce press freedom,” a widening government crackdown on critical voices in recent weeks has dashed hopes for greater freedom of expression. Secular revolutionary activists, bloggers and journalists have been targeted along with thousands of Brotherhood supporters and sympathizers, the majority of whom have been imprisoned on trumped up political charges. Four prominent activists (including iconic symbols of the 2011 Revolution Alaa Abdel Fattah and Ahmed Maher) languish behind bars for “taking part in unauthorized protests.” Meanwhile, three journalists working for the Al Jazeera English service remain in custody pending investigations on charges of ‘spreading lies and belonging to a terrorist cell.”

Another provision banning the closure of media outlets for what they broadcast or publish would have been plausible had it come before all channels linked to the Muslim Brotherhood were shut down in the wake of the military takeover of the country in July.

Critics meanwhile, cynically dismiss the provision giving citizens the right to freedom of assembly and demonstrations. They argue that a controversial new law criminalizing protests without prior permission from the authorities nullifies the provision.

And while the revised charter says freedom of belief is “absolute’–whereas the previous charter said it was “protected’– the freedom to practice religion and to establish places of worship is restricted to believers in the three “divine faiths’: Christianity, Islam and Judaism. This leaves the country’s Baha’is –who have long suffered discrimination –without protection or rights and may subject them to further persecution. Shia Muslims too face harassment in Egypt, according to the US State Department’s religious freedom 2012 report. Persistent hate speech culminated in the lynching of four Shias by a mob of ultraconservative Salafis in the village of Abu Musallim in Greater Cairo in June Earlier this month, a group of Canadian Shia pilgrims were barred entry into the country and were turned back by security officials.

But the biggest disappointment for secular activists and pro-democracy groups has been the retention of disputed provisions giving the military special privileges and allowing the continuation of military trials for civilians. Article 204 says that “civilians can be tried by military judges for attacks on armed forces, military installations, and military personnel.” Critics fear the provision could be applied to protesters, journalists and dissidents. For the next two presidential terms, the armed forces will also have the right to name the defense minister — an arrangement that positions the military as the main power broker, giving it autonomy above any civilian oversight. Moreover, the charter fails to ensure transparency for the armed forces’ budget allowing it to remain beyond civilian scrutiny.

“Failure of the charter to curb the military’s privileges paves the way for a bigger role for the army in becoming the main power broker,” said Hossam el-Hamalawy, a journalist and member of the Revolutionary Socialists Movement which played a key role in the 2011 mass uprising that toppled President Hosni Mubarak.

Despite its shortcomings, the charter is widely expected to be endorsed in the upcoming referendum. The majority of non-Islamists — a term often used to refer to Egypt’s leftists, liberals and Christians — are likely to approve the new charter simply because they yearn for a return to the stability and security they once enjoyed under authoritarian President Hosni Mubarak. An economic recession and rising unemployment have taken their toll on weary Egyptians whose livelihoods have been disrupted by the work stoppages and ongoing street protests. The economy had been on the brink of collapse before Saudi Arabia and other oil-rich Gulf states offered Egypt a multi-billion dollar rescue package to shore it up.

Analysts say the “yes” vote will not be an endorsement of the charter per se but rather, a nod of approval for the return of the military to power. They say the constitution will pass as an endorsement of Defense Minister General Abdel Fattah El Sissi, the country’s de facto ruler, who on Saturday confirmed he would run in the country’s next presidential elections “if the army gives me a mandate and if the people of Egypt ask me to do so”. General Sissi is idolized by millions of Egyptians who see him as the “saviour of the Revolution” despite the repressive measures used by the military to silence dissent since Morsi’s ouster.

Meanwhile, supporters of the ousted Islamist president have vowed to boycott what they call the “military” vote and are urging others to do likewise. Sheikh Youssef Qaradawi, a prominent Qatari-based Muslim Brotherhood cleric — who faces trial in absentia after the interim government branded him a ‘terrorist’ — has issued a religious edict or “fatwa” prohibiting Egyptians from voting in the referendum.

Some political groups have also declared their intention to boycott the vote while others have announced their outright rejection of the charter. The Strong Egypt Party, established in 2012 by former Brotherhood member Abdel Moneim Aboul Fottouh has said it opposes the constitution on grounds that “it fails to promote social justice and gives too much power to the President.” Four of the party’s members were arrested last week in Cairo for hanging up posters promoting a “no” vote. The April Six Movement — one of two main groups that organized and planned the mass protests that led to Hosni Mubarak’s overthrow — has also announced it would stay away from the ballot box, citing “the violent crackdown on Islamist protesters” as a reason. Other revolutionary groups like the Third Square — a loose coalition of leftists, liberals and moderate Islamists opposing both the military and the Muslim Brotherhood — have also said they would refrain from voting.

The enthusiasm and vigour that characterized the polls held after Mubarak’s overthrow have been replaced by disengagement and the mood of apathy that prevailed during the autocratic era of Hosni Mubarak. When asked if they will vote in the referendum, many ordinary Egyptians will answer, “What constitution? We want food for our children.” Many of them say they will not stand in line and wait for hours as they did in previous polls held during the last three years.

“I voted for Morsi in the last presidential election,” Mohamed Abdalla, a bearded taxi driver said. “What good did that do? Where is my vote now?”

This article was posted on 13 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org