20 May 2019 | Campaigns -- Featured, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Dear President Juncker,

Dear First Vice-President Timmermans,

Dear Vice-President Ansip,

Dear Commissioner Gabriel,

Dear Director General Roberto Viola,

The undersigned stakeholders represent fundamental rights organizations, the knowledge community (in particular libraries), free and open source software developers, and communities from across the European Union. The new Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market has been adopted and, as soon as it is published in the Official Journal, Member States will have two years to implement the new rules. Article 17, on ‘certain uses of protected content by online services’, foresees that the European Commission will issue guidance on the application of this Article.

The undersigned organisations have, on numerous occasions throughout the legislative debate on the copyright reform, expressed their very explicit concerns (1) about the fundamental and human rights questions that will appear in the implementation of the obligations laid down on online content-sharing service providers by Article 17. These concerns have also been shared by a wide variety of other stakeholders, the broad academic community of intellectual property scholars, as well as Members of the European Parliament and individual Member States. (2)

We consider that, in order to mitigate these concerns, it is of utmost importance that the European Commission and Member States engage in a constructive transposition and implementation to ensure that the fears around automated upload filters are not realized.

We believe that the stakeholder dialogues and consultation process foreseen in Article 17(10) to provide input on the drafting of guidance around the implementation of this Article should be as inclusive as possible. The undersigned organisations represent consumers and work to enshrine fundamental rights into EU law and national-level legislation.

These organisations are stakeholders in this process, and we call upon the European Commission to ensure the participation of human rights and digital rights organisations, as well as the knowledge community (in particular libraries), free and open source software developers, and communities in all of its efforts around the transposition and implementation of Article 17. This would include the planned Working Group, as well as other stakeholder dialogues, or any other initiatives at consultation level and beyond.

Such broad and inclusive participation is crucial for ensuring that the national implementations of Article 17 and the day-to-day cooperation between online content-sharing service providers and rightholders respects the Charter of Fundamental Rights by safeguarding citizens’ and creators’ freedom of expression and information, whilst also protecting their privacy. These should be the guiding principles for a harmonized implementation of Article 17 throughout the Digital Single Market.

Yours sincerely

Balázs Dénes

Executive Director

Civil Liberties Union for Europe (Liberties)

• Association for Progressive Communications

• APADOR-CH

• ApTi Romania

• Article 19

• Associação D3 – Defesa dos Direitos Digitais

• Associação Nacional para o Software Livre – Portugal

• Bits of Freedom

• BlueLink Foundation

• Center for Media & Democracy

• Centrum Cyfrowe Foundation

• Civil Liberties Union for Europe

• Coalizione Italiana Libertà e Diritti civili

• COMMUNIA association for the Public Domain

• Creative Commons

• Digital courage

• Digitalegeshellschaft

• Electronic Frontier Finland

• Electronic Frontiers Foundation

• Elektronisk Forpost Norge

• epicenter.works

• European Digital Rights (EDRi)

• Fitug e.v.

• Hermes Center

• Hivos

• Homo Digitalis

• Human Rights Monitoring Institute

• Hungarian Civil Liberties Union

• Index on Censorship

• International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA)

• Irish Council for Civil Liberties

• IT-Pol Denmark

• La Quadrature du Net

• Metamorphosis Foundation

• Nederlands Juristen Comité voor de Mensenrechten (NJCM)

• Open Rights Group

• Peace Institute

• Privacy First

• Rights International Spain

• Vrijschrift

• Wikimedia Deutschland e. V.

• Wikimedia Foundation

• Xnet

Notes

1 Human rights and digital rights organisations: https://www.liberties.eu/en/news/delete-article-thirteen-open-letter/13194

2 Academics from the leading European research centres: https://www.create.ac.uk/blog/2019/03/24/the-copyright-directive-articles-11-and-13-must-go-statement-from-european-academics-in-advance-of-the-plenary-vote-on-26-march-2019/

Max Plank Institute: https://www.ip.mpg.de/fileadmin/ipmpg/content/stellungnahmen/Answers_Article_13_2017_Hilty_Mosconrev-18_9.pdf

Universities: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3054967

Researchers: https://www.southampton.ac.uk/assets/imported/transforms/content-block/UsefulDownloads_Download/A6F51035708E4D-9EA3582EE9A5CC4C36/Open%20Letter.pdf

UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Opinion/Legislation/OL-OTH-41-2018.pdf[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1558113426313-ebe0f776-1ffe-2″ taxonomies=”4883″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Apr 2019

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1556538283972{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/index-report-2018-legislation-bannerv2.png?id=106464) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Targeting the messenger: Journalists ensnared by national security legislation” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”As security – rather than protecting rights and freedoms – becomes the top priority of governments worldwide, laws have increasingly been used to obstruct the work of media professionals in the 35 countries that are in or affiliated with the European Union (EU35).” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project, which monitors violations against media professionals in 43 countries, has received 269 reports of cases where national laws in the EU35 have been obstacles to media freedom between 2014 and 2018.

This includes everything from the hundreds of journalists jailed in Turkey following the 2016 failed coup to the seizure of a BBC journalist’s laptop in the United Kingdom, as well as Spain’s Citizens Security Law.

Mapping Media Freedom’s data highlights that the misuse of national security legislation to silence government critics is growing. Of the 269 cases, 67 happened in 2018 and 77 in 2017. There were 81 reports in 2016, 34 in 2015 and only 10 in 2014.

The increase in incidents may be the result of rapidly changing political contexts in individual countries such as Turkey, but it also reflects a continental trend, as incidents have increased in countries including the UK, France, Spain and Germany.

Mapping Media Freedom’s numbers reflect only what has been reported to the platform. We have found that journalists under-report incidents they consider minor, commonplace or part of the job, or where they fear reprisals. In some cases, Mapping Media Freedom correspondents have identified incidents retrospectively as a result of comments on social media or reports appearing only after similar incidents have come to light.

EU governments in particular need to be mindful that loosely-drafted national security laws are often copied by far more restrictive regimes to support their repression of critical media.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”106465″ img_size=”full”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-file-pdf-o” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_custom_heading text=”Anti-terror legislation” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]In light of recent terrorist attacks in Europe, governments have passed stricter counter-terrorism laws. However, the measures have been cynically exploited to criminalise government critics or silence critical media.

Turkey is an egregious case. This phenomenon started small where dismissive official rhetoric was aimed at small segments – such as Kurdish journalists – but over time expanded to extinguish whole newspapers or television networks that espoused critical viewpoints on government policy.

After the 2016 coup attempt, the trend intensified further. Hundreds of journalists have been arrested, dismissed from their jobs or sent to prison under state of emergency decrees and anti-terror laws passed by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government.

In one case, in July 2018, three pro-Kurdish newspapers and a television station were closed down by order of an emergency decree. Under the decree, all assets, rights and documents and the debt owed to the shuttered media institutions and associations were transferred to the treasury.

In many cases, critical media companies and dissenting journalists are charged under the anti-terror act for spreading “propaganda for a terrorist organisation”. Many are charged for supporting peace with Kurdish separatists or just for expressing solidarity with others who face government reprisals. For example, in January 2018, five journalists — Ragıp Duran, Hüseyin Aykol, Mehmet Ali Çelebi, Ayşe Düzkan and writer Hüseyin Bektaş — were sent to prison for participating in a solidarity campaign for the shuttered pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem newspaper.

But the trend toward the criminalisation of journalism that makes governments uncomfortable has spread beyond Turkey.

In 2015, five websites were blocked without judicial oversight in France. The administrative blocking came from the interior ministry on grounds that they “incite or defend terrorism”, under the Terrorism Act.

Even jokes can land journalists in trouble. French police searched the office of community station Radio Canut in Lyon in 2016 and seized the recording of a radio programme after two presenters were accused of “incitement to terrorism”. They had been talking about protests by police officers which had been taking place in France at the time. One of the presenters was put under judicial supervision and forbidden to host the radio programme until he appeared in court.

In Spain, comedian Facu Díaz was taken to court in 2015 for a satirical sketch from his online comedy show. The satirist faced charges under a law that criminalises the “glorification of terrorism” with punishment of up to two years in prison.

Governments are also using terror laws to spy on journalists. In 2014, police in the UK admitted they had used powers under terror legislation to obtain the phone records of Tom Newton Dunn, political editor of The Sun newspaper, to investigate the source of a leak in a political scandal. Police used powers under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which circumvents another law that requires police to have approval from a judge to get disclosure of journalistic material. In September 2018, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the UK’s mass surveillance regime violated human rights.

But the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Bill – a piece of legislation which critics argue will have a significant negative impact on media freedom in addition to other freedoms – continued its passage through Parliament, and has already been passed by the House of Commons. The final hearing in the House of Lords took place on 15 January 2019. It was sent back to the House for further consideration after some amendments.

The bill would criminalise publishing pictures or video clips of items such as clothes or flags in a way that raises “reasonable suspicion” that the person doing it is a member or supporter of a terrorist organisation. It would also criminalise watching online content that is likely to be helpful to a terrorist. No terrorist intent is required. The offence would carry a prison sentence of up to 15 years.

Parliament’s own human rights watchdog, the Joint Committee on Human Rights, has recommended that the former clause be withdrawn or amended because it “risks a huge swathe of publications being caught, including… journalistic articles”. The government has not accepted the recommendation.

“The bill would introduce wide-ranging new border security powers,” said Joy Hyvarinen, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship. “A journalist could be stopped without any suspicion of wrongdoing. It would be an offence not to answer questions or hand over materials, with no protection for confidential sources.”[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Law enforcement – security measures” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Measures designed to protect law enforcement officers or increase their powers have also become a threat for journalists.

These measures are sometimes the result of a state of emergency declared in a country. While the state of emergency in Turkey after the 2016 coup attempt is a prime example, the same has happened elsewhere.

In France, measures declared after the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris were used to ban photographer NnoMan from covering a protest in the city in 2016. The police justified the decree by the young man’s presence “at several demonstrations against police violence or the proposed labour law” which ended up in violent disorders, but failed to mention that NnoMan had a press card.

In other cases, the threat comes from ordinary laws. Spain’s Citizens Security Law punishes public protests in front of government buildings and the “unauthorised use” of images of law enforcement authorities or police.

In 2017, a Spanish police union filed a lawsuit against Mónica Terribas, a journalist for Catalunya Rádio, accusing her of “favouring actions against public order”. The union claimed she urged citizens in Catalonia to report on police movements during the referendum on independence, and that such information could help terrorists, drug dealers and other criminals.

The passing of a similar law has raised eyebrows in Bavaria, where the state parliament granted law enforcement broad new powers to act without “concrete suspicion” in May 2018. The law gives police new powers to access mobile phones, computers and cloud-based data. Law enforcement officers are allowed to amend or delete the information they recover under the legislation.

Provisions also include extending “preventative detention” powers where there is fear of public disorder, under which police can detain people for up to three months – previously two weeks – without prior judicial approval. Under the legislation, detainees can ask judges to review the legality of their detention, but prisoners must bring the cases themselves and have no right to state-provided lawyers for this purpose.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Official secrets – leaks” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Official secrets acts are another way in which legislation can obstruct media freedom.

In May 2017, six journalists were called to testify by authorities in the German state of Niedersachsen after the publication of articles that contained leaked information about law enforcement errors made during terror investigations. They were told they would face large fines if they refused to testify. The German Journalists Association called the procedure “intimidation” and “a risk for source protection”.

In the UK, a proposal is being considered that could lead to journalists being jailed for up to 14 years for obtaining leaked official documents. The major overhaul of the Official Secrets Act – to be replaced by an updated Espionage Act – would give courts the power to increase jail terms against journalists receiving official material. The new law, should it get approval, would see documents containing “sensitive information” about the economy fall foul of national security laws for the first time.

Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive of Index on Censorship, said: “It is unthinkable that whistleblowers and those to whom they reveal their information should face jail for leaking and receiving information that is in the public interest.”[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Case studies” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”Deniz Yücel, Turkey correspondent for Die Welt” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Deniz Yücel

The case of Deniz Yücel epitomises how journalism that is critical to the Turkish government, Erdoğan or their associates is being equated with terrorism.

Yücel, a Turkish-German dual national, was working as a correspondent for German newspaper Die Welt when he was taken into police custody on 17 February 2017, and was formally arrested on 27 February 2017.

He is one of hundreds of journalists arrested in Turkey since the 2016 coup attempt on charges of sedition and “spreading propaganda of a terrorist organisation and inciting the public to hatred and hostility” under the Turkish anti-terror act.

“This law is Turkey’s own Sword of Damocles that the state holds on freedom of expression,” said Özgün Özçer, Turkey correspondent for Mapping Media Freedom. “Journalists regularly face investigations when they report on the army’s crimes, the judiciary’s unfair verdicts, state oppression and so forth.

“Ironically, the propaganda charge is also a tool to allow government propaganda to prevail over the truth. It hides what truly happened and discredits reality to protect the state’s own version of the facts – the real propaganda.”

In Yücel’s case, “spreading propaganda for a terrorist organisation” amounted to a report he wrote about the energy minister after the minister’s email account was hacked by a group of activists. Six Turkish journalists were arrested for the same reason, but tried separately.

Yücel was subject to pre-trial detention until February 2018, when he was released. In the same month, his court case began. Prosecutors are seeking up to 18 years in prison.

Yücel returned to Germany after the intervention of Chancellor Angela Merkel and is being tried in absentia.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Axier López and Spain’s gag law” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Axier López

In March 2016, Axier López was fined €601 for posting photographs of police making an arrest.

López, a journalist for Basque country magazine Argia, had posted two photos on Twitter of police arresting a woman who had failed to appear in court.

Under the Citizens Security Law 2015 – which critics call the “gag law” – disseminating photos of police officers “that would endanger their safety or that of protected areas or put the success of an operation at risk” can incur in fines of up to €30,000.

According to the People’s Party, which was in power when the law was passed, the aim of the law is to protect officers on duty, but police associations and even citizens’ associations have used it to target journalists. The legislation was introduced after a wave of anti-austerity protests in the country.

“Several journalists have been sanctioned with heavy administrative fines for taking photos at public demonstrations and events,” said Silvia Nortes, Spain correspondent for Mapping Media Freedom. “Others have even suffered judicial measures against investigative journalism, mainly in political corruption cases.”

Although the fine has since been revoked by a Catalan court, López said the law criminalised journalism, and digital newspaper Diagonal wrote: “This is the first time that a journalist is fined by the gag law.”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

About this report

This report is part of a series based on data submitted to Mapping Media Freedom. This report reviewed 269 incidents involving investigative journalists from the 35 countries in or affiliated with the European Union between May 2014 and 30 October 2018.

Mapping Media Freedom identifies threats, violations and limitations faced by media workers in 43 countries — throughout European Union member states, candidates for entry and neighbouring countries. The project is co-funded by the European Commission and managed by Index on Censorship as part of the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF).

Index on Censorship is a UK-based nonprofit that campaigns against censorship and promotes freedom of expression worldwide. Founded in 1972, Index has published some of the world’s leading writers and artists in its award-winning quarterly magazine, including Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Samuel Beckett and Kurt Vonnegut. Index promotes debate, monitors threats to free speech and supports individuals through its annual awards and fellowship program.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Acknowledgements

AUTHOR Alessio Perrone

EDITING Adam Aiken, Sean Gallagher, Ryan McChrystal with contributions by Jodie Ginsberg, Joy Hyvarinen and Paula Kennedy and Mapping Media Freedom correspondents: João de Almeida Dias Adriana, Borowicz, Valeria Costa-Kostritsky, Ilcho Cvetanoski, Jonas Elvander, Amanda Ferguson, Dominic Hinde, Investigative Reporting Project Italy, Linas Jegelevicius, Juris Kaza, David Kraft, Lazara Marinkovic, Fatjona Mejdini, Mitra Nazar, Silvia Nortes, Platform for Independent Journalism (P24), Katariina Salomaki, Zoltan Sipos, Michaela Terenzani, Pavel Theiner, Helle Tiikmaa, Christina Vasilaki, Lisa

Weinberger

DESIGN Matthew Hasteley

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”106454″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”106452″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”106450″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”106451″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

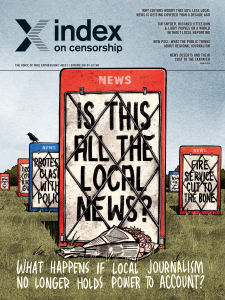

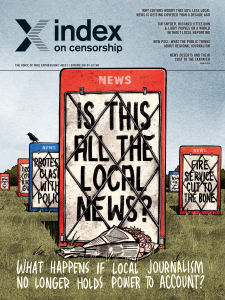

29 Mar 2019 | Campaigns -- Featured, Magazine, Press Releases, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”97% of editors of local news worry that the powerful are no longer being held to account ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Ninety seven per cent of senior journalists and editors working for the UK’s regional newspapers and news sites say they worry that that local newspapers do not have the resources to hold power to account in the way that they did in the past, according to a survey carried out by the Society of Editors and Index on Censorship. And 70% of those respondents surveyed for a special report published in Index on Censorship magazine are worried a lot about this.

The survey, carried out in February 2019 for the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, asked for responses from senior journalists and current and former editors working in regional journalism. It was part of work carried out for this magazine to discover the biggest challenges ahead for local journalists and the concerns about declining local journalism has on holding the powerful to account.

The survey found that 50% of editors and journalists are most worried that no one will be doing the difficult stories in future, and 43% that the public’s right to know will disappear. A small number worry most that there will be too much emphasis on light, funny stories.

There are some specific issues that editors worry about, such as covering court cases and council meetings with limited resources.

Twenty editors surveyed say that they feel only half as much local news is getting covered in their area compared with a decade ago, with 15 respondents saying that about 10% less news is getting covered. And 74% say their news outlet covers court cases once a week, and 18% say they hardly ever cover courts.

The special report also includes a YouGov poll commissioned for Index on public attitudes to local journalism. Forty per cent of British adults over the age of 65 think that the public know less about what is happening in areas where local newspapers have closed, according to the poll.

Meanwhile, 26% of over-65s say that local politicians have too much power where local newspapers have closed, compared with only 16% of 18 to 24-year-olds. This is according to YouGov data drawn from a representative sample of 1,840 British adults polled on 21-22 February 2019.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]The Index magazine special report charts the reduction in local news reporting around the world, looking at China, Argentina, Spain, the USA, the UK among other countries.

Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley said: “Big ideas are needed. Democracy loses if local news disappears. Sadly, those long-held checks and balances are fracturing, and there are few replacements on the horizon. Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be.”

She added: “If no local reporters are left living and working in these communities, are they really going to care about those places? News will go unreported; stories will not be told; people will not know what has happened in their towns and communities.”

Others interviewed for the magazine on local news included:

Michael Sassi, editor of the Nottingham Post and the Nottingham Live website, who said: “There’s no doubt that local decision-makers aren’t subject to the level of scrutiny they once were.”

Lord Judge, former lord chief justice for England and Wales, said: “As the number of newspapers declines and fewer journalists attend court, particularly in courts outside London and the major cities, and except in high profile cases, the necessary public scrutiny of the judicial process will be steadily eroded,eventually to virtual extinction.”

US historian and author Tim Snyder said: “The policy thing is that government – whether it is the EU or the United States or individual states – has to create the conditions where local media can flourish.”

“A less informed society where news is replaced by public relations, reactive commentary and agenda management by corporations and governments will become dangerously volatile and open to manipulation by special interests. Allan Prosser, editor of the Irish Examiner.

“The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial. Belgian journalist Jean Paul Marthoz.

The special report “Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?” is part of the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Note to editors: Index on Censorship is a quarterly magazine, which was first published in 1972. It has correspondents all over the world and covers freedom of expression issues and censored writing

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on Is this all the Local News?

Index on Censorship’s spring 2019 issue asks Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account? We explore the repercussions in the issue.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on iTunes and Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the Local News?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores what happens to democracy without local journalism, and how it can survive in the future.

With: Richard Littlejohn, Libby Purves and Tim Snyder[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]