The woman exposing the propaganda puppet masters

Dr Emma Briant, one of the key researchers who uncovered the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018

The vortex of misinformation, conspiracy theories, hatred and lies that we know as the unacceptable face of the internet has been well documented in recent years. Less well documented are the players behind these campaigns. But a small and growing group of journalists and researchers are working on shining a light on their activities. Dr Emma Briant is one of them. The professor, who is currently an associate at the Center for Financial Reporting and Accountability, University of Cambridge, is an internationally recognised expert who has researched information warfare and propaganda for nearly two decades. Her approach is that she doesn’t just research one party in the information war. Instead Briant considers each opponent, even those in democratic states, a breadth and detail that is important. As she tells me you miss half the story if you concentrate on single examples.

“This is a world in which there is an information war going on all sides and you can’t understand it without looking at all sides. There isn’t a binary of evil and pure. In order to understand how we can move forward in more ethical ways we need to understand the challenge that we are facing in our world of other actors who are trying to mislead us,” Briant says.

“There are powerful profit-making industries that are reshaping our world. We need to better research and understand that, to not simply expose some in isolated campaigns like they are just bad apples,” she adds.

Briant is perhaps best known for her work on Cambridge Analytica. She was central in exposing the data scandal related to the firm and Facebook at the time of the USA’s 2016 election. So what drove her to this area of research?

“My PhD looked at the war on terror and how the British and Americans were coordinating and developing their propaganda apparatus and strategies in response to changing media forms and changing warfare. Now that led me to meet Cambridge Analytica or rather its predecessor, the firm SCL group. Cambridge Analytica were using the kind of propaganda that had been used in the military, but in this case in elections, in democratic countries.”

The groundwork for this research was laid much earlier, when Briant lived as a child in Saudi Arabia around the time of the Gulf War. She was shocked to find lines and lines of Western newspapers censored with black pen, to the point you couldn’t read them, and pro-US and anti-Iraq propaganda everywhere.

“I was amazed by the efforts at social control,” she said.

Then, during her first degree, she studied international relations and politics when 9/11 happened and, as she says, “the world changed”.

“I was really very concerned about what we were being fed, about the spin of the Iraq war,” says Briant.

Like many she was inspired by a teacher, in her case Caroline Page.

“[Page] wrote a book on Vietnam and propaganda, and she had interviewed people in the American government and I was amazed that a woman could just go over to America and interview people in politics and in government and get really amazing interviews with high level officials. This really inspired me.”

Briant was motivated by both Page’s example and her specific work.

“She wanted to really find out what was going on and understand the actors behind the propaganda. And that is what really fascinates me most. Who’s behind the lies and the distortions? That’s why I’ve taken the approach that I have, both in looking at power in organisations like governments and how that’s deployed, and looking at how we can govern that power in democracies better.”

Because of Briant’s all-sided approach, she says she can attract the ire of people across the spectrum. People who focus only on Russia, for instance, might dislike that Briant critiques the British government. Conversely, people who are critics of the UK and US government call into question whether she should challenge Russian or Chinese propaganda. But, as she reiterates, “it’s really important to have researchers who are willing to take on that difficult issue of not only understanding a particular actor but understanding the conflict, protecting ordinary people and enabling them to have media they can trust and information online which is not deceptive.”

Criticism of her work has at times taken on a sinister edge. Briant is, sadly, no stranger to threats, trolling and other forms of online harassment.

“It’s very difficult to even just exist online if you’re doing powerful work, without getting trolled,” Briant says.

“The type of work that I do, which isn’t just analysing public media posts and how they spread, but is also looking at specific groups’ responsibilities and basically researching with a journalistic role in my research, that kind of thing tends to attract more harassment than just looking at online observable disinformation spread. Academics doing such work require support.”

Briant cites the case of Carole Cadwalladr, a journalist at the Guardian, as an example of how online campaigns are used to silence people. Like Briant, Cadwalladr pointed the looking glass at those behind the misinformation that spread in the lead-up to the EU referendum. Cadwalladr experienced extreme online harassment, as well as a lengthy and very expensive legal battle. Taken by Arron Banks, the case had all the hallmarks of being a SLAPP, a strategic lawsuit against public participation, namely, a lawsuit that has little to no legal merit. Its purpose is instead to silence the accused through draining them of emotional, physical and financial resources.

Briant has not been the subject of a SLAPP herself but has experienced other attempts to threaten, intimidate and silence her. Meanwhile, the threat of lawfare lingers in the background and has affected her work.

“Legal harassment has a real impact on what you feel like you are able to say. At one point after the Cambridge Analytica scandal it felt like I couldn’t work on highly sensitive work with a degree of privacy without the threat of being hacked or legal threats to obtain data or efforts to silence me. You cannot develop research on powerful actors and corrupt or deceptive activities as a journalist or a researcher without knowing your work is secure,” Briant says.

“Legal harassment has a real impact on what you feel like you are able to say. At one point after the Cambridge Analytica scandal it felt like I couldn’t work on highly sensitive work with a degree of privacy without the threat of being hacked or legal threats to obtain data or efforts to silence me. You cannot develop research on powerful actors and corrupt or deceptive activities as a journalist or a researcher without knowing your work is secure,” Briant says.

The ecosystem might be changing. New legislation has been proposed that will make using SLAPPs harder in the UK, where they are most common (the US, by comparison, has laws in place to limit them). But, as Briant highlights, there is more than one way to skin a cat.

“I don’t think people really understand the silencing effect of threat, not necessarily even receiving a letter but the potential of people to open up your private world. The exposure of journalism activities before an investigation is complete enables people to use partial information to misrepresent the activities, it can even put sources at risk,” she says.

While Briant believes these harassment campaigns can affect anyone doing the sort of work that she and Cadwalladr do, she says we can’t ignore the gender dynamic.

“Trolling and harassment affects a lot of different women and women are much more likely to experience this than men who are doing powerful work challenging people. This is just true. It’s been shown by Julie Posetti and her team, and it’s also the case if you look at other minorities or vulnerable communities.”

Of course if Briant was just a bit player people might not care as much. Instead, Briant has given testimony to the European Parliament and had her work discussed in US Congress. She’s written one book, co-authored another and has contributed to two major documentary films (one being the Oscar-shortlisted Netflix film The Great Hack). In today’s world, the attacks she has received have become part of the price people are paying for successful work. Still it’s an unacceptable price, one that we need to speak about more.

Briant is doing that, as well as more broadly carrying on with her research. She’s also writing her next two books, one of which revisits Cambridge Analytica. In Briant fashion, it places the company in a wider context.

“I’m looking at different organisations and discussing the transformation of the influence industry. This is really a very new phenomenon. Digital influence mercenaries are being deployed in our elections and are shaping our world.”

1972: Nixon went to China, BBC banned McCartney and Index was published

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

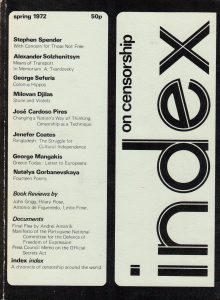

The first issue of Index on Censorship magazine, in March 1972.

You may have heard that the 70s were different. In 1972, when the first issue of Index magazine was launched, no one knew that 20 years later there would be an influential economic bloc called the European Union. The Beatles’ had only just split. The World Trade Center in New York was being built, while Sir Edward Heath was the prime minister of the United Kingdom.

Fifty years on and some things remain. Queen Elizabeth’s reign goes on and celebrates its 70th anniversary in 2022. Dictatorships and censorship, which should be trapped in history books, continue to torment the lives of many. And as a result, Index on Censorship remains vigilant, defending freedom of expression and giving voice to those who are silenced.

As we celebrate our 50th anniversary, we go back in time and remember the remarkable events that happened in 1972.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”1″][vc_column_text]January 30th: British soldiers shoot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest in Derry, Northern Ireland. Fourteen people were killed on this day known as “Bloody Sunday”. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”2″][vc_column_text]February 1st: Paul McCartney and the Wings release “Give Ireland back to the Irish” in the UK. It would be banned by the BBC, nine days later. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”3″][vc_column_text]February 5th: Airlines in the United States begin to inspect passengers and baggage. Tough to imagine that people traveled without any surveillance. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”4″][vc_column_text]February 17th: British Parliament votes to join the European Common Market. In 2020, the United Kingdom would leave the European Union. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”5″][vc_column_text]February 21st: Richard Nixon becomes the first US president to visit China, seeking to establish positive relations in a meeting with Chinese leader Mao Zedong, in Beijing.

Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon during Nixon’s historical visit to China in 1972. Photo: Ian Dagnall/Alamy

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”6″][vc_column_text]March 15th: The Godfather, starring Marlon Brando and Al Pacino, premieres in New York. It wins Best Picture and Best Actor (Brando) at the 45th Academy Awards.

Al Pacino and Marlon Brando in the Godfather. The first film of one the most successful franchises of all time was released in 1972. Photo: All Star Library/Alamy

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”7″][vc_column_text]June 18th: British European Airways Trident crashes after takeoff from Heathrow to Brussels, killing all 118 people on board. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”8″][vc_column_text]July 1st: Feminist magazine Ms, founded by Gloria Steinem, publishes its first issue, with Wonder Woman on the cover.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”9″][vc_column_text]August 4th: Uganda dictator Idi Amin orders the expulsion of 50,000 Asians with British passports.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”10″][vc_column_text]September 4th and 5th: 11 members of the Israeli Olympic team are murdered by a Palestinian terrorist group in the second week of the 1972 Olympics in Munich.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”11″][vc_column_text]September 21st: Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos declares martial law. In 2022, his son Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos is running for president. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”12″][vc_column_text]October 13th: A flight from Uruguay to Chile crashes in the Andes Mountains. Passengers eat the flesh of the deceased to survive. Sixteen people are rescued two months later.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”13″][vc_column_text]November 30th: BBC bans “Hi, Hi, Hi”, by Paul McCartney and The Wings, due to its drug references and suggestive sexual content. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”14″][vc_column_text]December 7th: Apollo 17 is launched and the crew takes the famous “blue marble” photo of the entire Earth.

The earth seen from the Apollo 17 spacecraft. Photo: NASA/Alamy

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”15″][vc_column_text]December 28th: Kim Il-Sung takes over as president of North Korea. He’s the grandfather of the country’s current leader, Kim Jong-un. [/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”16″][vc_column_text]December 30th: US President Richard Nixon halts bombing of North Vietnam and announces peace talks in Paris, to be held in January 1973. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

They “have come to rob you of your name and language”

In the very first edition of Index on Censorship, published 50 years ago almost to the day, we raised the case of Mykhaylo Osadchy, a Ukrainian journalist and poet, who had been arrested for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”. In a secret trial in his hometown of Lviv in September 1972 he was sentenced to seven years in prison and five years of exile.

An extract from The Mote, Osadchy’s lightly fictionalised memoir of a dissident writer, was published in the Autumn 1972 edition of Index. It provides a unique picture of the life of an intellectual in Ukraine under Soviet rule. “I had committed every vile deed that mankind throughout his existence could ever commit,” he writes. “I had never had the slightest suspicion of what a hostile element I was, or how hostile my thoughts had been.”

Cat and Mouse in the Ukraine by Victor Swoboda from 1973 is a lengthy but fascinating study of contemporary writers struggling, and often failing, to stay on the right side of the censor. Swoboda highlights the significance of the unpublished poem To the Kurdish Brother by Vasyl Symonenko, a writer celebrated by the Soviets as a hero of Communism but taken up by dissidents after the posthumous samizdat publication of his critical diaries. The poem tells “the Kurd” to fight chauvinists who “have come to rob you of your name and language”. It continues: “our fiercest enemy, chauvinism, fattens on the blood of harassed peoples”. It is not hard to see who the “Kurd” in the poem was intended to represent. In 1968 Mykola Kots, an agricultural college lecturer, was arrested for circulating 70 copies of the poem in which “the Kurd” had been replaced with “the Ukrainian”. He received the same sentence as Osaschy.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Index continued to support writers from Ukraine. As a result, we were the first to publish the work of Ukraine’s most celebrated contemporary writer, Andrei Kurkov, in English. The November 1993 issue contained an excerpt from The Cosmopolitan Anthem, a short story denounced at the 1991 All-Union Writers Conference in Yalta as “anti-Russian”. The story is, if anything, an attack on unthinking nationalism. Its narrator, an American with mixed Polish-Palestinian heritage, finds himself fighting on both sides of the Vietnam War and Afghanistan. The title of the story refers to the soldier’s utopian dreams of creating a unifying anthem to appeal to people’s better nature.

In 1999 we published extracts from Ukraine’s Forbidden Histories, which combined oral histories collected by the British Library with contemporary photographs by Tim Smith. It remains a striking document of the imprint Ukraine’s past atrocities left on the country. The authors pay tribute to the work of the organisation Memorial (now banned by Putin) in documenting the crimes of the Stalin era. The extracts include testimonies of the Babi Yar massacre of the city’s Jewish population, which has only been officially recognised in 1991. A monument to Babi Yar was reported to have been bombed during the recent invasion.

In 2001, Vera Rich, who devoted her life to translating Ukrainian and Belarusian literature, wrote Who is Ukraine? on the tenth anniversary of the country’s independence. Despite her obvious passion for the country (she translated the national poet Taras Shevchenko) it provides a clear-eyed look at the complicated nature of Ukrainian identity. “For a country to survive… a sense of national identity is required. But the question of what that identity should be has by no means been resolved,” she writes.

Finally, no collection of archive articles from Index on Ukraine would be complete without something from Andrei Aliaksandrau, who worked for Index for several years before returning to his native Belarus. He has now been in prison for over a year after being arrested by the Lukashenka regime. His piece, Brave New War from December 2014, reports on the information war being waged in Ukraine. It is a brilliant piece of reporting. “The principles of an information war remain unchanged: you need to de-humanise the enemy. You inspire yourself, your troops and your supporters with a general appeal which says: ‘We are fighting for the right cause – that is why we have the right to kill someone who is evil.’ What has changed is the scale of propaganda and the number of different platforms used to distribute it. In a time of social networks and with the whole world online, there is no need to throw leaflets over enemy lines, instead you hire 1,000 internet trolls.”

Aliaksandrau has been silenced, for now. But we will continue to report on Ukraine in tribute to him and the other courageous dissidents who have inspired the work of Index over the past five decades.

Research by Guilherme Osinski and Sophia Rigby