13 Apr 2016 | Academic Freedom, mobile

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

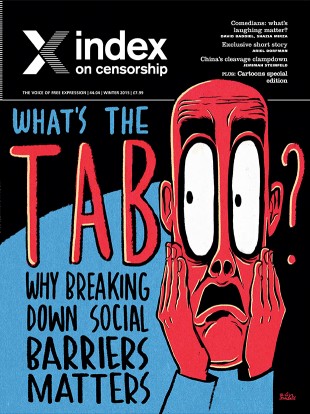

A drawing by French cartoonist t0ad

Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right. It reinforces all other human rights, allowing society to develop and progress. The ability to express our opinion and speak freely is essential to bring about change in society.

Free speech is important for many other reasons. Index spoke to many different experts, professors and campaigners to find out why free speech is important to them.

Index on Censorship magazine editor, Rachael Jolley, believes that free speech is crucial for change. “Free speech has always been important throughout history because it has been used to fight for change. When we talk about rights today they wouldn’t have been achieved without free speech. Think about a time from the past – women not being allowed the vote, or terrible working conditions in the mines – free speech is important as it helped change these things” she said.

Free speech is not only about your ability to speak but the ability to listen to others and allow other views to be heard. Jolley added: “We need to hear other people’s views as well as offering them your opinion. We are going through a time where people don’t want to be on a panel with people they disagree with. But we should feel comfortable being in a room with people who disagree with us as otherwise nothing will change.”

Human rights activist Peter Tatchell states that going against people who have different views and challenging them is the best way to move forward. He told Index: “Free speech does not mean giving bigots a free pass. It includes the right and moral imperative to challenge, oppose and protest bigoted views. Bad ideas are most effectively defeated by good ideas – backed up by ethics, reason – rather than by bans and censorship.”

Tatchell, who is well-known for his work in the LGBT community, found himself at the centre of a free speech row in February when the National Union of Students’ LGBT representative Fran Cowling refused to attend an event at the Canterbury Christ Church University unless he was removed from the panel; over Tatchell signing an open letter in The Observer protesting against no-platforming in universities.

Tatchell, who following the incident took part in a demonstration urging the UK National Union of Students to reform its safe space and no-platforming policies, told Index why free speech is important to him.

“Freedom of speech is one of the most precious and important human rights. A free society depends on the free exchange of ideas. Nearly all ideas are capable of giving offence to someone. Many of the most important, profound ideas in human history, such as those of Galileo Galilei and Charles Darwin, caused great religious offence in their time.”

On the current trend of no-platforming at universities, Tatchell added: “Educational institutions must be a place for the exchange and criticism of all ideas – even of the best ideas – as well as those deemed unpalatable by some. It is worrying the way the National Union of Students and its affiliated Student Unions sometimes seek to use no-platform and safe space policies to silence dissenters, including feminists, apostates, LGBTI campaigners, liberal Muslims, anti-fascists and critics of Islamist extremism.”

Article continues below

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Stay up to date on free speech” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that defends people’s freedom to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution. We fight censorship around the world.

To find out more about Index on Censorship and our work protecting free expression, join our mailing list to receive our weekly newsletter, monthly events email and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns. See a sample of what you can expect here.

Index on Censorship will not share, sell or transfer your personal information with third parties. You may may unsubscribe at any time. To learn more about how we process your personal information, read our privacy policy.

You will receive an email asking you to confirm your subscription to the weekly newsletter, monthly events roundup and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Professor Chris Frost, the former head of journalism at Liverpool John Moores University, told Index of the importance of allowing every individual view to be heard, and that those who fear taking on opposing ideas and seek to silence or no-platform should consider that it is their ideas that may be wrong. He said: “If someone’s views or policies are that appalling then they need to be challenged in public for fear they will, as a prejudice, capture support for lack of challenge. If we are unable to defeat our opponent’s arguments then perhaps it is us that is wrong.

“I would also be concerned at the fascism of a majority (or often a minority) preventing views from being spoken in public merely because they don’t like them and find them difficult to counter. Whether it is through violence or the abuse of power such as no-platform we should always fear those who seek to close down debate and impose their view, right or wrong. They are the tyrants. We need to hear many truths and live many experiences in order to gain the wisdom to make the right and justified decisions.”

Free speech has been the topic of many debates in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks. The terrorist attack on the satirical magazine’s Paris office, in January 2015, has led to many questioning whether free speech is used as an excuse to be offensive.

Many world leaders spoke out in support of Charlie Hebdo and the hashtag #Jesuischarlie was used worldwide as an act of solidarity. However, the hashtag also faced some criticism as those who denounced the attacks but also found the magazine’s use of a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed offensive instead spoke out on Twitter with the hashtag #Jenesuispascharlie.

After the city was the victim of another terrorist attack at the hands of ISIS at the Bataclan Theatre in November 2015, President François Hollande released a statement in which he said: “Freedom will always be stronger than barbarity.” This statement showed solidarity across the country and gave a message that no amount of violence or attacks could take away a person’s freedom.

French cartoonist t0ad told Index about the importance of free speech in allowing him to do his job as a cartoonist, and the effect the attacks have had on free speech in France: “Mundanely and along the same tracks, it means I can draw and post (social media has changed a hell of a lot of notions there) a drawing without expecting the police or secret services knocking at my door and sending me to jail, or risking being lynched. Cartoonists in some other countries do not have that chance, as we are brutally reminded. Free speech makes cartooning a relatively risk-free activity; however…

“Well, you know the howevers: Charlie Hebdo attacks, country law while globalisation of images and ideas, rise of intolerances, complex realities and ever shorter time and thought, etc.

“As we all see, and it concerns the other attacks, the other countries. From where I stand (behind a screen, as many of us), speech seems to have gone freer … where it consists of hate – though this should not be defined as freedom.”

In the spring 2015 issue of Index on Censorship, following the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Richard Sambrook, professor of Journalism and director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff University, took the opportunity to highlight the number journalists that a murdered around the world every day for doing their job, yet go unnoticed.

Sambrook told Index why everyone should have the right to free speech: “Firstly, it’s a basic liberty. Intellectual restriction is as serious as physical incarceration. Freedom to think and to speak is a basic human right. Anyone seeking to restrict it only does so in the name of seeking further power over individuals against their will. So free speech is an indicator of other freedoms.

“Secondly, it is important for a healthy society. Free speech and the free exchange of ideas is essential to a healthy democracy and – as the UN and the World Bank have researched and indicated – it is crucial for social and economic development. So free speech is not just ‘nice to have’, it is essential to the well-being, prosperity and development of societies.”

Ian Morse, a member of the Index on Censorship youth advisory board told Index how he believes free speech is important for a society to have access to information and know what options are available to them.

He said: “One thing I am beginning to realise is immensely important for a society is for individuals to know what other ideas are out there. Turkey is a baffling case study that I have been looking at for a while, but still evades my understanding. The vast majority of educated and young populations (indeed some older generations as well) realise how detrimental the AKP government has been to the country, internationally and socially. Yet the party still won a large portion of the vote in recent elections.

“I think what’s critical in each of these elections is that right before, the government has blocked Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook – so they’ve simultaneously controlled which information is released and produced a damaging image of the news media. The media crackdown perpetuates the idea that the news and social media, except the ones controlled by the AKP, are bad for the country.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538130760855-7d9ccb72-bf30-2″ taxonomies=”571, 986″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Mar 2016 | Greece, mobile, News and features

Stills by Belgian artist Kris Verdonck, from A Two Dogs Company on Vimeo.

“My job is to make good art,” said Belgian artist Kris Verdonck. “I have no interest in being deliberately offensive or provocative.”

Verdonck was speaking at an event at the Onassis Cultural Centre in Athens last week, entitled Art Freedom Censorship. Featuring a range of international speakers and organisations, including Index on Censorship, the event was inspired by recent works and performances that have been shutdown in Greece following public outcry.

In Verdonck’s case, that outcry came predominantly from one man: a local priest.

Last year Onassis Cultural Centre put on one of Verdonck’s works, Stills, a series of oversized, slow-mo nudes that move within confined spaces. The artist has been showing the images around Europe, projected on to buildings associated with historical dictators. In Athens, the show lasted just one day before a priest complained. A staff member from Onassis was temporarily held in police custody before the centre agreed to halt the projections.

Also speaking at Art Freedom Censorship was director Pigi Dimitrakopoulou, who presented a play, Nash’s Balance, at Greece’s National Theatre in January, before it was pulled mid-run after vehement protests and threats of violence. The work used text taken from a book by Savvas Xiros, a convicted member of the 17 November group, which the Greek government considers a terrorist organisation.

In one of the more heated debates of the evening, Dimitrakopoulou said she hadn’t given much thought to censorship before being embroiled in the scandal. “I always thought I was too conservative to be affected by such things.” She spoke of a “political tsunami” that engulfed the show. “I expected a reaction, but more related to the work,” she said, adding that she believed most critics hadn’t seen it.

Greek journalist and publisher Elias Kanellis, who had been outspokenly against the decision to use the 17 November text, stood by his criticism but clarified that he never called for it to be censored. “Criticism is the founding principle of democracy,” he said. “But what if I were to publish Jihadi propaganda?”

Discussions also included a look at the role of the church in Greece today. Stavros Zoumboulakis, president of the supervisory council of the Greek National Library, spoke of orthodox priests refusing to admit the nation is now a post-Christian society, with only a tiny percentage attending mass. But Xenia Kounalaki, a journalist from Greek daily newspaper Kathimerini, argued the issue was less about numbers of active worshipers, more a problem of top-down influence, which still extends into the nation’s education system.

Other speakers included former Charlie Hebdo columnist and author of In Praise of Blasphemy Caroline Fourest; Mauritanian filmmaker Lemine Ould M. Salem, who has run into difficulties with France’s film classification board over his documentary about Salafi fighters in Mali; and German director Daniel Wetzel, who is presenting a theatrical interpretation of Mein Kampf at Onassis in April.

Vicky Baker spoke at Art Freedom Censorship on behalf of Index on Censorship

1 Mar 2016 | Magazine, Statements, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015 Extras

Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine, in a speech to the §2 – Libraries and Democracy conference in Umea, Sweden.

When I was nine, ten and eleven, my mother, my brother and I had a weekly ritual of driving to the local library, a flat modern building with big glass windows. We’d spend a quiet hour wandering up and down its carpeted corridors, picking out two or three plastic-covered books to take home to read.

All sorts of people found stories, history and biographies within their reach.

I have measured out my life in library books: from weekly visits to Bristol libraries, to school in Pittsburgh – a city which pays tribute to the greatest library supporter of them all Andrew Carnegie – to further study at the great Colindale newspaper archive library, and perhaps the most exciting celebrity library spot, standing next to the poet and librarian Philip Larkin in the neighbourhood butchers in Hull.

US poet laureate Rita Dove believes that libraries provide: “A window into the soul and a door into the world.” There are two types of freedom captured in that thought: The freedom to think, and the freedom to find out about others.

Books, magazines and newspapers are a door into the world and that’s why over centuries governments have tried to stop them being opened.

When that door opens on to the world, who knows what people might think or do? That door is not open to everyone now, or in the past. And when it comes to the freedom to express oneself: to write, draw, paint, act or protest then restrictions have often been levied by governments and other powerful bodies to stop the wider public being allowed those too.

Over the centuries, often, books were only made available to some. Sometimes they were written in a language that only a tiny group of people knew. When paper was expensive, books were for the few, not the many. In times gone by education was also expensive (and it still is in many places); those who were allowed to learn reading and writing were once in the minority.

That’s why public libraries, open to all and funded from the public purse, are so important. Their existence helped the many get access to what the few had held close to their chests; information, literature, inspiration.

US businessman and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie was one of the world’s most enthusiastic endowers of libraries. He helped fund more than 2,000 libraries around the United States plus hundreds more in the UK and beyond, because when he was a poor teenager, a wealthy man, Colonel James Anderson, opened up his private library of 400 books to Andrew and other working boys on Saturday nights, and this, Carnegie believed, made a huge difference to his life chances, and his ability to rise from poor, struggling beginnings to be a successful and wealthy steel magnate.

Carnegie believed in libraries’ power to do good. To open people’s minds. To help build knowledge. To help the ordinary person be introduced to ideas that might never otherwise be seen.

Of course, the history of libraries is much older than Carnegie’s time, stretching back to the Romans, Greeks, Chinese and Islamic libraries, where archives of important documents were kept.

Libraries hold history; documents that tell us what was bought and sold in ancient Greece; or how a Roman senator spoke. They inform us about the reality of other times, and allow us to learn from that past.

That’s why conquering armies have looked to destroy libraries and museums. Part of imposing a new present on a population is sometimes about re-writing the past. From the Library at Alexandria, to the Mosque library at Chinguetti to the Roman library on the Palatine Hill. If documents had not been preserved, we would know far less. We can do more than guess what might have happened, we can actually KNOW details, because records are still available.

In the 21st century libraries are under threat from many directions. As governments and local councils cut public spending, libraries in many western countries, including in the United Kingdom, are being closed down. Does that point to a lack of need or desire for such things? Have libraries become redundant?

In this new age of enlightenment is our thirst for knowledge less desperate than in previous generations or is our thirst quenched by easy access to hundreds of television channels and the internet? Indeed, with electronically accessible information free to anyone with a computer, is the internet the ultimate library, rendering its brick and glass-built equivalents redundant, in the same way the printing press marginalised the illuminated manuscript?

We in Europe are more free than previous generations have ever been to learn, find and understand. With our zillions of instant access points for information and discussion, we can look at Facebook, Twitter and thousands of ideas online in the twitch of mouse click after all. But does that access bring more understanding or deeper knowledge? And what is the future role then of a library?

Librarians are much needed as valuable guides: to help students and other readers to learn techniques to sift information, question its validity and measure its importance. To understand what to trust and what to question; and that all information is not equal. Students need to be able to weigh up different sources of research. The University of California Library System saw a 54% decline in circulation between 1991 to 2001 of 8,377,000 books to 3,832,000. It is shocking that some students are failing themselves by not using a broad range of books, and journals that are free from their university libraries to widen and deepen their understanding.

Both libraries and newspapers in their analogue form gave us the opportunity to stumble over ideas that we might not have otherwise encountered. Over there, on that page opposite the one we are reading in a newspaper, is an article about Chilean architecture that we knew nothing about it, but suddenly find a spark of interest in, and over there on the library shelf next to Agatha Christie, is Henning Mankell, a new author to us, and one that suddenly sounds like one we might like to read. And then off we go on a new winding track towards knowledge; one that we didn’t even know we wanted to explore. But that analogue world of stumbled-upon exploration is closing down. We have to make sure that we still have the equipment to carry on stumbling down new avenues and finding out about new writers, and history that we never knew we would care about.

Technology tends to remove the “stumbling upon”, by taking us down straight lines. Instead it prompts us to read or consume more of the same. Technology learns what we like, but it doesn’t know and cannot anticipate what might fascinate us in a chance, a random, encounter. In a world where we remove the unexpected then we miss out on expanding our knowledge. Something that libraries have always offered. The present is all too easily an echo chamber of social media where we follow only the people we agree with, and where we fail to engage with the arguments of those with whom we disagree. Is the echo chamber being enhanced by the linear nature of the digital library, the digital bookstore and the digital newspaper? AND if we follow only those that we like and agree with, do we lull ourselves into believing that those are the only opinions and beliefs out there. And we are so unused to disagreement that we want to close it down. We are somehow afraid to have it in the same room as us. Somehow we seem to be stumbling on towards a world where disagreement is frowned upon, and not embraced as a way of finding what is out there.

This is just one challenge to freedom of expression and thought. There are others.

Recently at Index on Censorship, we heard from Chilean-American writer Ariel Dorfman, a long-time supporter and writer for us…. that his play, Death and the Maiden, was being banned by a school in New Jersey because some parents didn’t like the language contained in it. In other words it offended or upset somebody. Meanwhile Judy Blume’s books about the realities of teenage life, including swearing and teenage pregnancy, gets her banned from US libraries and schools.

But isn’t fiction, theatre and art about connecting with the real, isn’t it about challenging people to think, and to be provoked?

When a film has been banned from our cinemas or a book banned from distribution has it meant no one is keen to read it? In fact the opposite is usually true, people flock to find out what it is or to watch the film wherever they can. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, A Clockwork Orange and DH Lawrence’s novel Sons and Lovers found new audiences because they were banned. Monty Python’s controversial film Life of Brian was once marketed here in Sweden as the film so funny, it was banned in Norway!! (As you can imagine it did very well here in Sweden.)

Increasingly there are loud voices saying that we shouldn’t think about the unpleasant bits in the world, that we should ignore the difficult or traumatic because it is too complicated, or too ugly to have in the room. In a special editorial published at the time of the Charlie Hebdo killings, the South African Mail and Guardian said; “The goals of terrorism, if we are to dignify utter insanity with aims, are fear and polarisation.” If we live in a society where we think we are not allowed to speak about subjects; where they are considered too controversial, where appearing on a platform with someone is somehow seen as a tacit nod to agreeing with them, are giving into those goals?

So what can those living in Europe do to enhance or defend freedom of expression and what are the role of libraries? Firstly, we should never stop learning about our history. Remember periods where freedoms of expression, of thought, of living in a non traditional way, or practising a religion that was not state sanctioned, were not laid out as European rights as they are today. From witch trials, to the Edict of Nantes, to social stigma of unmarried women, to children abused by adults. There are moments in every family’s history, when someone had a desperate need for some secret, some taboo, some injustice to be talked about. To be put under the public spotlight.

Given that historical, but personal, reflection, perhaps each of us can have a clearer understanding of why freedom of expression as a right is something worth defending today.

Freedom of expression has always had a role in challenging injustice and persecution. Some argue that without freedom of expression we would not have other freedoms. Freedom of expression also includes offering groups that have historically been ostracised or sidelined or ignored — a chance to put their views, to be part of the wider debate, to be chosen to join a television chat show. Europe is a diverse society, all those voices should be heard.

Another point about enhancing freedom of expression in Europe, and outside, is that a lively and vigorous and diverse media is extremely important. So we should fight against control of the media by a single corporation, or by increased government influence. We need newspapers, and broadcasters, that cover what is happening, and don’t ignore stories because someone would rather those stories were not covered.

And another role for libraries of the future is as debate houses – a living room – at the centre of communities where people of different backgrounds come together to hear and discuss issues at the heart of our societies. And to meet others in their community. These neutral spaces are increasingly needed.

The value of passionate argument is often valued less than it should be. Where debates or arguments are driven underground, those who are not allowed to speak somehow obtain a glamour, a modern martydom. We must allow dissent and argument. We must let people whose ideas we abhor speak. Freedom of speech for those we like and agree with is no freedom at all.

There are those that dismiss freedom of speech as an indulgence defended by the indulged or the middle class or the left wing or the right wing or some other group that they would like not to hear from. However throughout history, freedom of speech and thought and debate has been used by the less powerful to challenge the powerful. Governments, state institutions, religious institutions. And to argue for change. That is not an indulgence.

And if you believe someone else’s arguments are ill founded, incorrect or malicious, then arguing a different point of view in a public place, a library, or a university hall, is much more powerful, than saying you are not allowed to say those things because we don’t like or disagree with them. To make those arguments, to understand what is happening we need to be able to access knowledge, libraries must continue to be community spaces where people can delve for that research and find out about the world, and themselves.

Libraries and those who support them have often been defenders of the right to knowledge. Because at the heart of any library is the idea of a freedom to think and discover.

We should remember that reading something never killed anyone. Watching a play didn’t either. If you find something that you disagree with, even disagree strongly, it is not the same as a dagger through your heart, as someone told me it was last summer in Italy.

As Turkish writer Elif Shafak said recently the response to a cartoon is another cartoon, the response to a play is another play. We are and can be prepared to listen, read or watch things that we disagree with. Listen to the argument; argue back with your own. Consider the evidence. The point of speech is to arrive at truth, and no one should be offended by that.