8 May 2014 | Belarus, News and features

(Photo: Ivan Uralsky / Demotix)

Authorities in Belarus have been targeting human rights activists ahead of this weekend’s start of the International Ice Hockey Federation’s world championship in Minsk.

At least 17 political and civic activists were detained between 26 April and 6 May to prevent the organising of protests during the championship, which begins on 9 May. Another five are either in detention or being sought for questioning by police. All have been accused of minor hooliganism and sentenced to administrative detention of up to 25 days.

Such “preventive arrests” are common in Belarus. One of the activists, Pavel Vinahradau, who is known for his numerous detentions, opted to leave Minsk until the end of the championship. He had previously been summoned by the police: “They made it clear that either I go to Berezino (a small town 100 km outside Minsk) till 3 June, or I go to Akrestsina (a detention centre in Minsk). I choose Berezino,” Vinahradau wrote on Facebook.

A website called Totalitizator asks its visitors make predictions about which activists will be detained next, for how many days and on what charges. For people who follow political news in Belarus it is not difficult to make a choice.

Potential foreign “troublemakers” are also being kept away from the tournament. On Wednesday, Martin Uggla, a human rights activist from Sweden, was denied entry to Belarus when he was detained at Minsk-2 National Airport. According to temporary visa-free travel requirements, hockey supporters with valid game tickets do not require visa. Despite the fact Martin had one, border guards told him he was being prohibited from entering the country.

Belarus’ president Alexander Lukashenko is known for his love for hockey – and his unfulfilled desire of a real international profile. Consistent tensions with the Western democracies and an unwillingness to ease his authoritarian grip has deprived Lukashenko’s international relations of impact. Fifty-six of the president’s last 100 international visits were to Russia and Kazakhstan, though he has travelled to Turkmenistan, Venezuela, China and Cuba, as well.

The ice hockey championship in Minsk is set to become Lukashenko’s marquee performance on the world stage. That is why the government is rounding up activist voices. Lukashenko wants to present a calm, hospitable and prosperous country led by a wise and caring leader. The picturesque façade cannot hide the problems afflicting Belarus: An unsustainable economy hooked on huge Russian subsidies and a dismal human rights record.

Belarus remains the only country in Europe that still imposes the death penalty. On 18 April, 23-year-old Pavel Sialiun was, according to reports, executed. Sialiun’s case is still under review by the UN Human Rights Committee.

Nine political prisoners are still in jail in Belarus, including well-known human rights defender Ales Bialiatski, and former presidential candidate Mikalay Statkevich. A recent report by FIDH says they are in a critical situation. Many dissidents suffer regular restrictions to “their means of support, quality of food and medical assistance”, including being deprived of meetings with relatives and subject to limits on correspondence.

“Politically motivated persecution of civil society representatives and of the opposition is a general trend, and the limitations on political and civil rights of Belarusian citizens are pervading, both in national legislation and in practice,” says another statement by 12 human rights groups that represent the ice hockey championship participating countries.

But people who raise these issues are not welcome in Minsk these days. Even foreign journalists who are accredited for the championship are obliged to receive a separate accreditation at the Belarusian Foreign Ministry if they wish to cover issues other than hockey while in Belarus.

But many in the country fear the real issues to cover will appear after the championship is over on 25 May.

“Putin invaded the Crimea four days after the Sochi Olympics. Let’s see if Lukashenko will be that quick with another clampdown on civil society. But I am sure he will settle all accounts with us after the championship,” a leader of one Belarusian NGOs told Index in Minsk last week.

Next year, the country will vote in the presidential election. So there is more ice to come in Belarus after international hockey is gone.

An earlier version of this article specifically stated that both Ales Bialiatski and Mikalay Statkevich have been deprived of meetings with relatives and subject to limits on correspondence. While this may have been true in the past, we have not been able to confirm that this is currently happening to the pair.

This article was posted on May 8, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Apr 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

State surveillance has been much publicised of late due to Snowden’s revelations, but allegations against the NSA and GCHQ are only one aspect of the international industry surrounding wholesale surveillance. Another growing concern is the emergence and growth of private sector surveillance firms selling intrusion software to governments and government agencies around the world.

Not restricted by territorial borders and globalised like every other tradable commodity, buyers and sellers pockmark the globe. Whether designed to support law enforcement or anti-terrorism programmes, intrusion software, enabling states to monitor, block, filter or collect online communication, is available for any government willing to spend the capital. Indeed, there is money to be made – according to Privacy International, the “UK market for cyber security is estimated to be worth approximately £2.8 billion.”

The table below, collated from a range of sources including Mother Jones, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Bloomberg, Human Rights Watch, Citizen Lab, Privacy International and Huffington Post, shows the flow of intrusion software around the world.

| Surveillance Company |

Country of Origin |

Alleged Countries of Use |

| VASTech |

South Africa |

Libya (137) |

| Hacking Team |

Italy |

Azerbaijan (160), Egypt (159), Ethiopia (143), Kazakhstan (161), Malaysia (147), Nigeria (112), Oman (134), Saudi Arabia (164), Sudan (172), Turkey (154), Uzebekistan (166) |

| Elbit Systems |

Israel |

Israel (96) |

| Creative Software |

UK |

Iran (173) |

| Gamma TSE |

UK |

Indonesia (132) |

| Narus |

USA |

Egypt (159), Pakistan (158), Saudi Arabia (164) |

| Cisco |

USA |

China (175) |

| Cellusys Ltd |

Ireland |

Syria (177) |

| Adaptive Mobile Security Ltd |

Ireland |

Syria (177), Iran (173) |

| Blue Coat Systems |

USA |

Syria (177) |

| FinFisher GmbH |

Germany |

Egypt (159), Ethiopia (143) |

Note: The numbers alongside the alleged countries of use are the country’s ranking from 2014 Reporters without Borders World Press Freedom Index 2014.

While by no means complete, this list is indicative of three things. There is a clear divide, in terms of economic development, between the buyer and seller countries; many of the countries allegedly purchasing intrusion software are in the midst of, or emerging from, conflict or internal instability; and, with the exception of Israel, every buyer country ranks in the lower hundred of the latest World Press Freedom Index.

The alleged legitimacy of this software in terms of law enforcement ignores the potential to use these tools for strictly political ends. Human Rights Watch outlined in its recent report the case of Tadesse Kersmo, an Ethiopian dissident living in London. Due to his prominent position in opposition party, Ginbot 7 it was discovered that his personal computer had traces of FinFisher’s intrusion software, FinSpy, jeopardising the anonymity and safety of those in Ethiopia he has been communicating with. There is no official warrant out for his arrest and at the time of writing there is no known reason in terms of law enforcement or anti-terrorism legislation, outside of his prominence in an opposition party, for his surveillance. It is unclear whether this is part of an larger organised campaign against dissidents in both Ethiopia and the diaspora, but similar claims have been filed against the Ethiopian government on behalf of individuals in the US and Norway.

FinFisher GmbH states on its website that “they target individual suspects and can not be used for mass interception.” Without further interrogation into the end-use of its customers, there is nothing available to directly corroborate or question this statement. But to what extent are private firms responsible for the use of its software by its customers and how robustly can they monitor the end-use of its customers?

In the US Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, there is a piece of guidance entitled Know Your Customer. This outlines steps to be undertaken by firms to identify what the end-use of its products is. This is a proactive process, placing the responsibility firmly with the seller to clearly identify and act on abnormal circumstances, or ‘red flags’. The guidance clearly states that the seller has a “duty to check out the suspicious circumstances and inquire about the end-use, end-user, or ultimate country of destination.”

Hacking Team has sold software, most notably the Remote Control System (RCS) to a number of countries around the world (see above). Citizen Lab, based out of the University of Toronto, has identified 21 countries that have potentially used this software, including Egypt and Ethiopia. In its customer policy, Hacking Team outlines in detail the lengths it goes to verify the end-use and end-user of RCS. Mentioning the above guidelines, Hacking Team have put into practice an oversight process involving a board of external engineers and lawyers who can veto sales, research of human rights reports, as well as a process that can disable functionality if abuses come to light after the sale.

However, Hacking Team goes a long way to obscure the identity of countries using RCS. Labelled as untraceable, RCS has established a “Collection Infrastructure” that utilises a chain of proxies around the world that shields the user country from further scrutiny. The low levels of media freedom in the countries purportedly utilising RCS, the lack of transparency in terms of the oversight process including the make-up of the board and its research sources, as well as the reluctance of Hacking Team to identify the countries it has sold RCS to undermines the robustness of such due diligence. In the words of Citizen Lab: “we have encountered a number of cases where bait content and other material are suggestive of targeting for political advantage, rather than legitimate law enforcement operations.”

Many of the firms outline their adherence to the national laws of the country they sell software to when defending their practices. But without international guidelines and alongside the absence of domestic controls and legislation protecting the population against mass surveillance, intrusion software remains a useful, if expensive, tool for governments to realise and cement their control of the media and other fundamental freedoms.

Perhaps the best way of thinking of corporate responsibility in terms of intrusion software comes from Adds Jouejati of the Local Coordination Committees in Syria, “It’s like putting a gun in someone’s hand and saying ‘I can’t help the way the person uses it.’”

This article was posted on 11 April, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Feb 2014 | Belarus, News and features

Join Index at a presentation of a new policy paper on media freedom in Belarus on 19 February, 2014, 15.00 at the Office for Democratic Belarus in Brussels.

This article is the second of a series based on the Index on Censorship report Belarus: Time for media reform.

The present media market started to take shape at the beginning of 1990s as Belarus became an independent state after the Soviet Union disintegrated. Unlike other post-Soviet states, the process of the denationalisation and privatisation of the state media was not in fact ever launched leaving state control and ownership over most of national media. While a number of independent media outlets were established in the 1990s, very few have managed to survive.

Current media are significantly affected by the political and economic situation after the presidential election of December 2010 that was followed by a severe clampdown on political opposition and civil society and periods of financial instability.

The authorities keep tight regulatory and economic control over the news media market. State-run media that are used as means of government propaganda enjoy significant financial support, while independent news media face economic discrimination that makes their position in the market more vulnerable.

Broadcast media

Broadcast media remain the primary source of information for most Belarusians. The overall reach of television is 98.4% of the population aged over 15, and its share in the media advertising market is over 50% of the total. This dominant position of television is the reason the state keeps this sphere under strict control. Most of broadcast media in Belarus are state-owned, and they enjoy significant financial support from the authorities. The state budget of Belarus for 2014 allocated 548 bn roubles (about £34m) for direct support of television and radio.

There are 262 TV and radio stations registered, 178 of them–68% of the total–are owned by the state. There is no formal Public Service Broadcaster (PSB) with an independent board and a commitment to impartiality. Four national channels are owned by the National State Television and Radio Company which also owns five radio channels and five regional TV and radio companies. Two more national channels, ONT and STV, are formally joint stock companies, but they are not publicly listed, and all their founders are state companies.

There is not a single independent national TV channel or a public service broadcaster in the country. Independent broadcast media that operates from abroad face restrictions. For instance, Belsat TV channel, which has been broadcasting in Belarusian from Poland since 2007, has been refused permission to open an official editorial office in Belarus. Belsat’s reporters face constant pressure and are subjected to warnings and detentions.

At the same time, a decision taken in November 2013 to prolong accreditation in Minsk of the editorial office of Euroradio, an independent radio station that also broadcasts in Belarusian from Poland, can be considered as a positive step.

The general process of licensing and frequency allocation in Belarus is complicated, not transparent and is controlled entirely by the government through licensing and frequency allocation processes.

Printed media

Economic leverages are used by the authorities of the country to control the printed news media market in Belarus. While state-owned newspapers have preferences in advertising market and distribution, independent publications fail to enjoy equal conditions, being restricted from distribution systems and advertising. Economic difficulties threaten operations of non-state socio-political newspapers, and thus restrict the access of the audience to independent sources of information.

The majority of printed media – 1,146 out of the total of 1,556 registered in Belarus as of 1 January 2014 – are privately owned. Most of the non-state newspapers are not news publishers but mainly advertising or publications for entertainment. According to BAJ, there are less than 30 socio-political newspapers, both national and regional, in Belarus that are publications with actual news journalism.

There is a significant amount of evidence to suggest that the non-state owned press in Belarus faces economic discrimination. Direct state subsidies to the state-owned printed media in 2014 are projected to be 64 bn roubles (about £4 m). It is claimed by the editors of several non-state newspapers, that the costs of paper and printing for independent newspapers are higher than for state-owned ones.

Another form of direct economic discrimination by the government is the influence of the state over the advertising market. The economy of Belarus is dominated by the state, with 70 per cent of its GDP being the output of state-owned companies. In practice this gives opportunities for the direct interference of the government in the distribution of advertising revenues. It is also the case that there is compulsory subscription to state-owned newspapers, both national and local, for employees of state-owned enterprises and organisations.

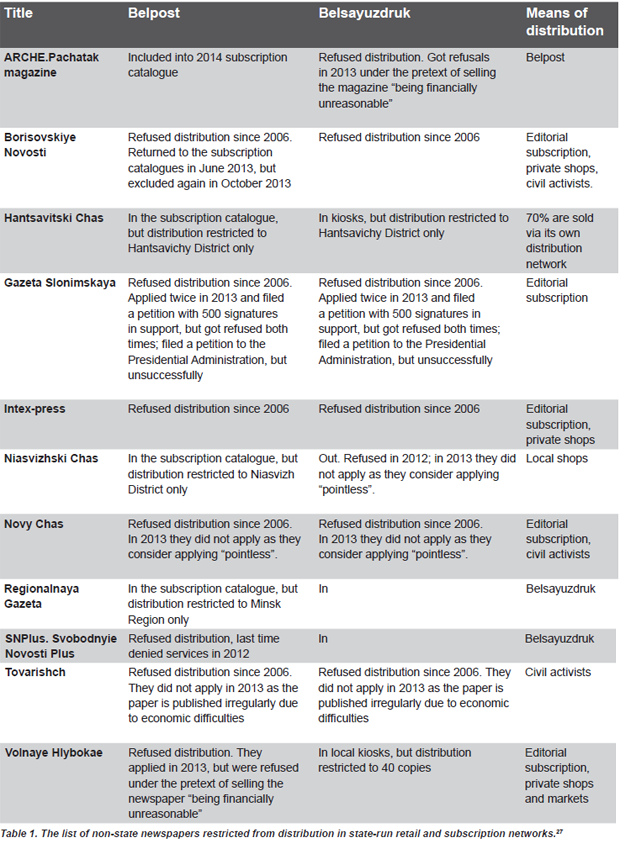

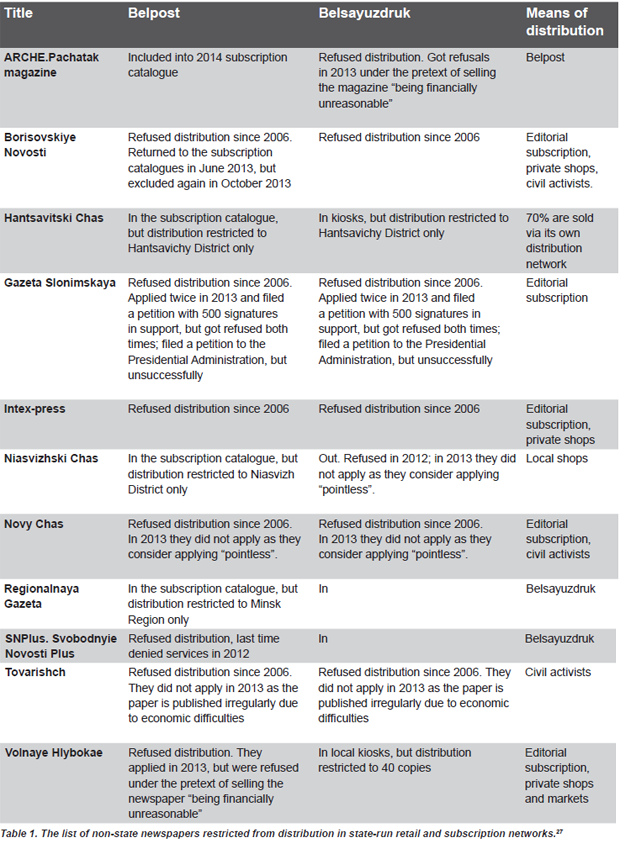

There is direct state intervention in the distribution of independent newspapers, which prevents their sale. At least eleven independent publications face restrictions to their distribution via state-run retail press distribution and subscription networks (Table 1). The distribution ban was imposed on the eve of the presidential election of 2006, when at least 16 independent newspapers were excluded from the subscription catalogue of Belposhta (Belarusian Post) and 19 had their contracts with Belsayuzdruk retail sales system cancelled. Due to the distribution restrictions several of them ceased to exist. Most of those that survived remain barred from state distributors and have had to either develop their own distribution systems or move completely online.

The authorities of the country persistently refuse to acknowledge the problem of distribution restrictions. Dzmitry Shedko, Deputy Minister of Information, wrote to Index request that “non-state media equally with state ones have a free access to state printing facilities and possibilities to distribute their publications through state press distribution structures.” The Deputy Minister points out that the law provides for the freedom of contract, and the authorities cannot interfere with the will of distribution companies to sign contracts with any particular mass media outlet.

In practice the reality is very different. In 2008 two independent newspapers, Nasha Niva and Narodnaya Volia, were returned to state distribution systems as a part of commitments the authorities of Belarus made to the European Union in order to re-launch a political dialogue with the EU. It proves a decision to lift the distribution restriction is political and can be dictated by the state.

Online media

The internet in Belarus is developing extensively, although it cannot still boast of the same audiences as broadcast media. Over 4.85 m Belarusians aged over 15 access the internet–12% more than a year ago–and over 80% of those with access go online every day. Sixty-eight percent of Belarus’s internet users go online through a high-speed broadband connection. The internet remains a relatively free domain of freedom of expression in the country, despite recent attempts by the government to put it under tighter control, as revealed in Belarus: Pulling the Plug report, produced by Index on Censorship in January 2013.

Growing internet penetration and the restrictions traditional media face offline has led to a significant development of online news media. For instance, several independent publications that stopped issuing printed versions due to distribution restrictions now only exist as websites. This is the case with Belorusskaya Delovaya Gazeta, once one of the leaders of non-state press, Salidarnasc or Khimik regional newspaper. Online versions of several existent newspapers reach a larger audience that their printed versions.

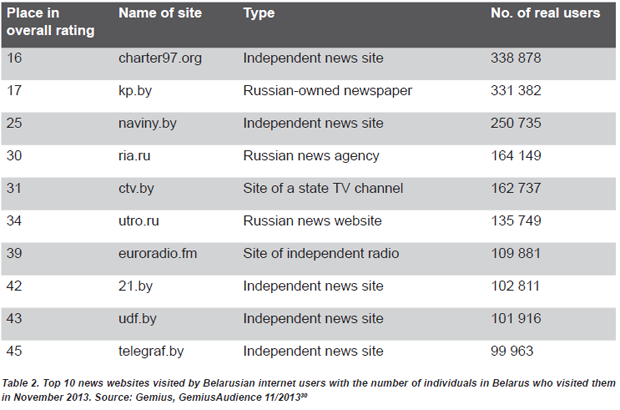

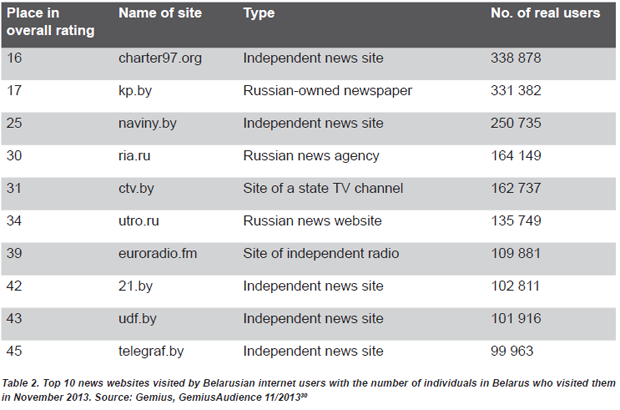

In general, independent online publications enjoy significantly greater popularity among internet users than pro-regime websites of state-run media.

This table represents online news publications only, but does not include the news sections of larger internet portals. It should be noted that they are much more popular then dedicated news publications. For instance, the news section of the largest Belarusian portal TUT.BY is visited by about 1 m Belarusians aged over 15 monthly. News sections of major Russian portals Mail.ru and Yandex.ru are ranked 2nd and 3rd as sources of online news for visitors from Belarus.

The two important trends of Belarus’s online news market are:

• Dedicated news websites are not the most popular online destinations for Belarusians;

• Russian websites have a significant market share in terms of Belarusian audience.

The top 20 news publications have a joint reach of no more than 25% of the total number of Belarusians online. If news sections of major portals are taken into consideration, this share is still around 45%. At the same time, Mail.ru, a Russian portal that is the most popular website among the Belarusian audience, has an audience share of 61.7% alone. Users appear to favour reading news on portals, where they can get other services and on news aggregators.

Social media sites are visited by 72.5% of Belarusian internet users, with Russian Odnoklassniki.ru and Vkontakte leading in this group as well. Four of the six most popular websites in Belarus are Russian portals or services.

There are serious limitations to the development of the online news media market. This is not due to government restrictions, but primarily due to economic factors. The total annual volume of the online advertising market in Belarus in 2013 is estimated to be $10.5 million US dollars. Despite 50% growth to 2012, Belarus still has one of the lowest advertising expenditure budgets per internet user in Europe. The market is very much dominated by its leaders, including Russian media companies that have significant resources to expand and currently enjoy a significant market share.

Case study: State and non-state press: Different media realities

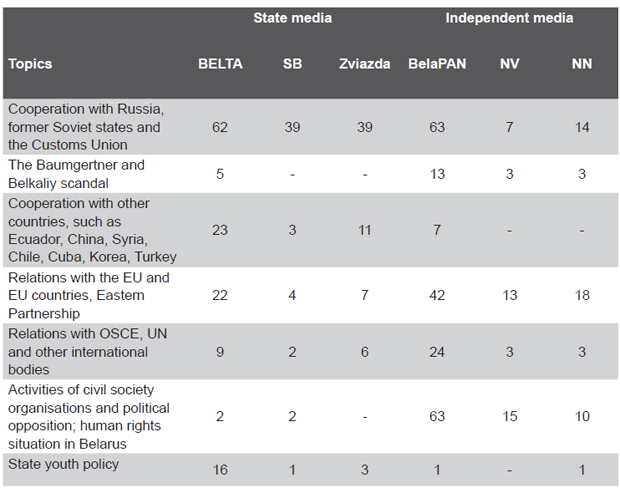

Index on Censorship in cooperation with Mediakritika.by, a Belarusian project dedicated to analysing and monitoring the national media landscape, conducted field research into the content published by state-owned and independent media (that is privately owned media that is free from political direction from the president and government). The research found clear differences between editorial policies of the media based on their ownership including the topics they cover and their approaches to coverage. The difference was particularly noticeable during major political campaigns, such as elections.

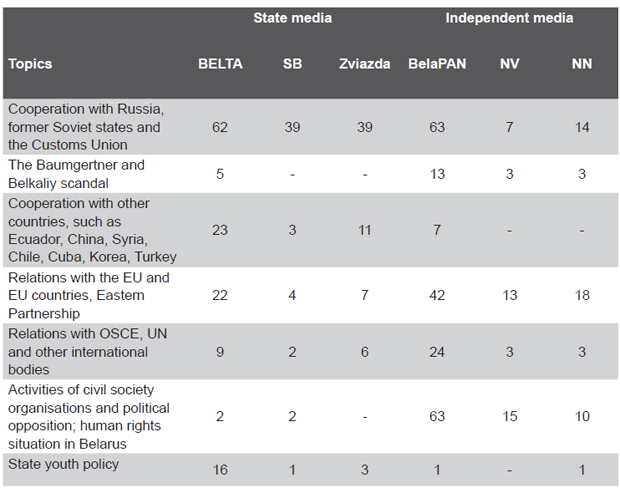

The research looked at the content of six Belarusian media outlets, analysed as presented at their websites in October 2013. They are two leading information agencies, state-owned BELTA and privately owned BelaPAN (presented online as Naviny.by), and four national newspapers, state-owned Sovetskaya Belorussiya (SB) and Zviazda, and independent Narodnaya Volia (NV) and Nasha Niva (NN).

The content was analysed in terms of presence of several specific topics (quantitative) and the way they were approached by the media (qualitative). The table below represents the number of articles covered or mentioned by the specified topics from the respective media outlets in October 2013:

On the first category, the coverage of relations with states from the former Soviet Union and the creation of a Customs Union (between Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan) which is part of the official foreign policy of Belarus, the state news agency BELTA dedicates significant coverage. BELTA also gives significant coverage to successful foreign policy partnerships by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and countries in South-East Asia and Latin America. The state media’s significant coverage of the Customs Union and relations with Russia is not matched by coverage of Belarus – EU relations. The analysis found there was little coverage of foreign policy analysis except the opinions of state officials.

The independent media also pays significant attention to the Russian – Belarusian relations, but there is significantly more coverage of Belarusian relations with the EU and other international institutions and organisations. For example, the number of news items on the “eastern” and “western” vectors produced by BelaPAN is almost the same; BELTA pays twice more attention to ex-Soviet countries, Russia first of all, than to cooperation with the West.

Even more dramatic differences are noted in the way state and independent media cover domestic politics. Within the state media politics is associated with (and consists of little more than) the statements and public speeches of the President. State media outlets even have “President” as a separate news section. BELTA’s “President” section, for instance, had more than 80 news items on activities and statements of the head of the state in October 2013.

The most significant difference between the state-owned media and the privately owned media is that there is almost no mention of the activities of the political opposition, while the independent media provides significant coverage of the activities of opposition political parties but also independent trade unions, civil society organisations and activists.

Human rights issues or repressive measures taken by the authorities are widely covered by the independent media. As can be seen in the table, the state media almost entirely ignores these issues. While the recent scandal with Vladislav Baumgertner, the CEO of the Russian Uralkaliy company, who was arrested in Minsk,34 generated significant headlines in the independent media in Belarus – and the media in Russia as well – it was hardly covered by the Belarusian state media; their coverage was reduced to quotes from President Lukashenko on the matter.

There have been no visible improvements of the situation with traditional news media since 2009 in Belarus. The state keeps dominating the broadcast media market and preserves tight control over printed publications. State-owned media are used as a tool for government propaganda, while independent socio-political press faces discrimination that limits their operational capacity and thus restricts the development of free and pluralistic media in the country. The internet re-shapes the news media market as it provides new opportunities for free flow of information and ideas, but its full-scale development as a free speech domain is hindered by economic peculiarities and attempts of state regulation.

Belarus media landscape: Recommendations

All forms of economic discrimination against non-state independent press should be eliminated, in particular:

• independent publications should be treated equally by the state system of press distribution and Belposhta subscription catalogues;

• the state has a pro-active duty to protect and promote freedom of expression and so should investigate anti-competitive practices including the charging of unequal prices for paper and the distribution services for publications for different types of ownership.

Reforms of the Belarusian media field should be launched, including de-monopolising of the electronic media, introducing public service media and creating a competitive media market. The outline of these reforms should result from a dialogue with professional community and civil society of the country.

Part 1 Belarus: Europe’s most hostile media environment | Part 2 Belarus: A distorted media market strangles independent voices | Part 3 Belarus: Legal frameworks and regulations stifle new competitors | Part 4 Belarus: Violence and intimidation of journalists unchecked | Part 5 Belarus must reform its approach to media freedom

A full report in PDF is available here

This article was published on 12 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

7 Feb 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Russia

(Image: Gonçalo Silva/Demotix)

The Sochi Winter Olympics opening ceremony is taking place today, and organisers have declared that a record 65 world leaders are attending. But numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. As it turns out, some of the biggest names in global politics will not be in the stands cheer on their athletes as the games are officially kick off. Indeed, quite a few won’t be taking the trip to Sochi at all. Barack Obama is sending a delegation including openly gay figure skater Brian Boitano in his place, and Angela Merkel, David Cameron and Francois Hollande are also staying away.

But while the International Olympic Committee’s Thomas Bach was less than impressed by the apparent boycott, labelling it an “ostentatious gesture” that “costs nothing but makes international headlines”, the absence of the big guns does give the lesser-known world leaders a chance to shine. Not all guests have been confirmed, but we’ve got the low-down on some of the the leaders the cameras might pan to during today’s festivities, or who could be spotted in the slopes over the coming weeks.

Alexander Lukashenko

(Image: Ivan Uralsky/Demotix)

Putin’s long time colleague and fellow ice hockey enthusiast surely wouldn’t miss the Winter Olympics for the world. The Belarusian president is known as “the last dictator in Europe”, his near 20 years in power having passed without a single free and fair election. Under his leadership, peaceful protests have been violently dispersed, and civil society activists and political opposition — including rival candidates from the 2010 presidential elections — have been jailed. A brand new report from Index also concludes that: “Belarus continues to have one of the most restrictive and hostile media environments in Europe.”

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

(Image: Philip Janek / Demotix)

The Turkish president made global headlines last summer, over his regime’s violent crackdown on the peaceful Gezi park demonstrations. Rather than accepting the protests were a manifestation of genuine grievances by his people, he blamed “foreign hands” and their “domestic collaborators” like many a less-than-democratic leader before him. His government was recently implicated in a big corruption scandal, and only yesterday, parliament approved controversial amendments to the country’s internet law. The new law, opposed by civil society, the opposition and international organisations alike, gives the government wide-reaching powers over the internet, effectively allowing them to block websites without court rulings, and gives them access to user data.

Viktor Yanukovych

(Image: Oleksandr Nazarov/Demotix)

The Ukrainian president’s failure to sign a treaty securing closer ties with the EU in November, sparked the country’s ongoing Euromaidan protests. The authorities response was heavy handed — police clashed with demonstrators and journalist were targeted, leading to international condemnation. They authorities even briefly implemented a highly repressive new law, among other things allowing security services to monitor the internet, and defining NGOs receiving funding from abroad as “foreign agents”. The law was, however, scrapped only days later following outrage from civil society. Meanwhile,Ukraine’s Prime Minister and government also stepped down, while Yanukovych took four days off ill. He’s back in the office now — just in time head to Sochi for a much-hyped meeting with Putin.

Nursultan Nazarbayev

(Image: Vladimir Tretyakov/Demotix)

Kazakhstan’s president has been in power since 1991, and during that time, allegations of human rights abuses, including attacks on demonstrators and independent media, as well as widespread corruption have been regularly levelled at him. In 2012, following clashed between the police and striking workers, the president, who already effectively controls the legislature and the judiciary, further extended his emergency powers. But Putin wouldn’t even be his only high-flying friend. In September, Kanye West performed at his grandson’s wedding. The reported price tag? $3 million. Did I mention the accusations of corruption? Meanwhile, former British prime minister Tony Blair spent two years advising Nazarbayev and his government on democracy and good governance — a deal which “produced no change for the better or advance of democratic rights in the authoritarian nation”.

Emomali Rahmon

(Image: Riccardo Valsecchi/Demotix)

He has been the head of the government of Tajikistan since 1992, and was in power during the country’s civil war, where 100,000 people lost their lives. Allegations of human rights abuses, including torture by security forces and arbitrary arrests, are widespread. Much of the media is state-controlled, and independent journalists face violence and intimidation. “Publicly insulting the president” can see you jailed for as long as five years. Recently, a prominent member of the opposition, Zaid Saidov, was sentenced to 26 years in prison following what has been described as a “politically motivated trial”. In Sochi, he is set to meet with not only Putin, but also Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

This article was posted on February 7 2014 at indexoncensorship.org