Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

This article was published on June 18, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

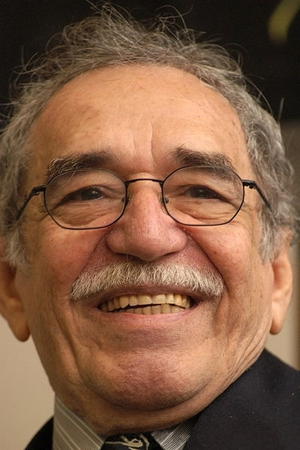

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for Index on Censorship magazine in 1997. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control”

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for Index on Censorship magazine in 1997. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control”

Some 50 years ago, there were no schools of journalism. One learned the trade in the newsroom, in the print shops, in the local cafe and in Friday-night hangouts. The entire newspaper was a factory where journalists were made and the news was printed without quibbles. We journalists always hung together, we had a life in common and were so passionate about our work that we didn’t talk about anything else. The work promoted strong friendships among the group, which left little room for a personal life.There were no scheduled editorial meetings, but every afternoon at 5pm, the entire newspaper met for an unofficial coffee break somewhere in the newsroom, and took a breather from the daily tensions. It was an open discussion where we reviewed the hot themes of the day in each section of the newspaper and gave the final touches to the next day’s edition.

The newspaper was then divided into three large departments: news, features and editorial. The most prestigious and sensitive was the editorial department; a reporter was at the bottom of the heap, somewhere between an intern and a gopher. Time and the profession itself has proved that the nerve centre of journalism functions the other way. At the age of 19 I began a career as an editorial writer and slowly climbed the career ladder through hard work to the top position of cub reporter.

Then came schools of journalism and the arrival of technology. The graduates from the former arrived with little knowledge of grammar and syntax, difficulty in understanding concepts of any complexity and a dangerous misunderstanding of the profession in which the importance of a “scoop” at any price overrode all ethical considerations.

The profession, it seems, did not evolve as quickly as its instruments of work. Journalists were lost in a labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control. In other words: the newspaper business has involved itself in furious competition for material modernisation, leaving behind the training of its foot soldiers, the reporters, and abandoning the old mechanisms of participation that strengthened the professional spirit. Newsrooms have become a sceptic laboratories for solitary travellers, where it seems easier to communicate with extraterrestrial phenomena than with readers’ hearts. The dehumanisation is galloping.

Before the teletype and the telex were invented, a man with a vocation for martyrdom would monitor the radio, capturing from the air the news of the world from what seemed little more than extraterrestrial whistles. A well-informed writer would piece the fragments together, adding background and other relevant details as if reconstructing the skeleton of a dinosaur from a single vertebra. Only editorialising was forbidden, because that was the sacred right of the newspaper’s publisher, whose editorials, everyone assumed, were written by him, even if they weren’t, and were always written in impenetrable and labyrinthine prose, which, so history relates, were then unravelled by the publisher’s personal typesetter often hired for that express purpose.

Today fact and opinion have become entangled: there is comment in news reporting; the editorial is enriched with facts. The end product is none the better for it and never before has the profession been more dangerous. Unwitting or deliberate mistakes, malign manipulations and poisonous distortions can turn a news item into a dangerous weapon.

Quotes from “informed sources” or “government officials” who ask to remain anonymous, or by observers who know everything and whom nobody knows, cover up all manner of violations that go unpunished.But the guilty party holds on to his right not to reveal his source, without asking himself whether he is a gullible tool of the source,manipulated into passing on the information in the form chosen by his source. I believe bad journalists cherish their source as their own life – especially if it is an official source – endow it with a mythical quality, protect it, nurture it and ultimately develop a dangerous complicity with it that leads them to reject the need for a second source.

At the risk of becoming anecdotal, I believe that another guilty party in this drama is the tape recorder. Before it was invented, the job was done well with only three elements ofwork: the notebook,foolproof ethics and a pair of ears with which we reporters listened to what the sources were telling us. The professional and ethical manual for the tape recorder has not been invented yet. Somebody needs to teach young reporters that the recorder is not a substitute for the memory, but a simple evolved version of the serviceable, old-fashioned notebook.

The tape recorder listens, repeats – like a digital parrot – but it does not think; it is loyal, but it does not have a heart; and, in the end, the literal version it will have captured will never be as trustworthy as that kept by the journalist who pays attention to the real words of the interlocutor and, at the same time, evaluates and qualifies them from his knowledge and experience.

The tape recorder is entirely to blame for the undue importance now attached to the interview. Given the nature of radio and television, it is only to be expected that it became their mainstay. Now even the print media seems to share the erroneous idea that the voice of truth is not that of the journalist but of the interviewee. Maybe the solution is to return to the lowly little notebook so the journalist can edit intelligently as he listens, and relegate the tape recorder to its real role as invaluable witness.

It is some comfort to believe that ethical transgressions and other problems that degrade and embarrass today’s journalism are not always the result of immorality, but also stem from the lack of professional skill. Perhaps the misfortune of schools of journalism is that while they do teach some useful tricks of the trade, they teach little about the profession itself. Any training in schools of journalism must be based on three fundamental principles: first and foremost, there must be aptitude and talent; then the knowledge that “investigative” journalism is not something special, but that all journalism must, by definition, be investigative; and, third, the awareness that ethics are not merely an occasional condition of the trade, but an integral part, as essentially a part of each other as the buzz and the horsefly.

The final objective of any journalism school should, nevertheless, be to return to basic training on the job and to restore journalism to its original public service function; to reinvent those passionate daily 5pm informal coffee-break seminars of the old newspaper office.

Index on Censorship magazine is proud to have had Gabriel García Marquez among its contributors – a long list which has also included Samuel Beckett, Chinua Achebe, Salman Rushdie and many other literary greats. Printed quarterly, the magazine mixes long-form journalism with short stories and extracts from plays – some of which have been banned or censored around the world. Subscribe here

On 7 March, a US federal judge granted the government’s motion to dismiss the majority of its criminal case against journalist Barrett Brown. The 11 dropped charges, out of 17 in total, include those related to Brown’s posting of a hyperlink that led to online files containing credit card information hacked from the private US intelligence firm Stratfor.

Brown, a 32-year old writer who has had links to sources in the hacker collective Anonymous, has been in pre-trial detention since his arrest in September 2012 – weeks before he was ever charged with a crime. Prior to the government’s most recent motion, he faced a potential sentence of over a century behind bars.

The dismissed charges have rankled journalists and free-speech advocates since Brown’s case began making headlines last year. The First Amendment issues were apparent: are journalists complicit in a crime when sharing illegally obtained information in the course of their professional duties?

“The charges against [him] for linking were flawed from the very beginning,” says Kevin M Gallagher, the administrator of Brown’s legal defense fund. “This is a massive victory for press freedom.”

At issue was a hyperlink that Brown copied from one internet relay chat (IRC) to another. Brown pioneered ProjectPM, a crowd-sourced wiki that analysed hacked emails from cybersecurity firm HBGary and its government-contracting subsidiary HBGary Federal. When Anonymous hackers breached the servers of Stratfor in December 2011 and stole reams of information, Brown sought to incorporate their bounty into ProjectPM. He posted a hyperlink to the Anonymous cache in an IRC used by ProjectPM researchers. Included within the linked archive was billing data for a number of Statfor customers. For that action, he was charged with 10 counts of “aggravated identity theft” and one count of “traffic[king] in stolen authentication features”.

On 4 March, a day before the government’s request, Brown’s defence team filed its own 48-page motion to dismiss the same set of charges. They contended that the indictment failed to properly allege how Brown trafficked in authentication features when all he ostensibly trafficked in was a publicly available hyperlink to a publicly available file. Since the hyperlink itself didn’t contain card verification values (CVVs), Brown’s lawyers asserted that it did not constitute a transfer, as mandated by the statute under which he was charged. Additionally, they argued that the hyperlink’s publication was protected free speech activity under the First Amendment, and that the application of the relevant criminal statutes was “unconstitutionally vague” and created a chilling effect on free speech.

Whether the prosecution was responding to the arguments of Brown’s defense team or making a public relations choice remains unclear. The hyperlink charges have provoked a wave of critical coverage from the likes of Reporters Without Borders, Rolling Stone, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the New York Times, and former Guardian columnist Glenn Greenwald.

Those charges were laid out in the second of three separate indictments against Brown. The first indictment alleges that Brown threatened to publicly release the personal information of an FBI agent in a YouTube video he posted in late 2012. The third claims that Brown obstructed justice by attempting to hide laptops during an FBI raid on his home in March of that year. Though he remains accused of access device fraud under the second indictment, his maximum prison sentence has been slashed from 105 years to 70 in light of the dismissed charges.

While the remaining allegations are superficially unrelated to Brown’s journalistic work, serious questions about the integrity of the prosecution persist. As indicated by the timeline of events, Brown was targeted long before he allegedly committed the crimes in question.

On 6 March 2012, the FBI conducted a series of raids across the US in search of material related to several criminal hacks conducted by Anonymous members. Brown’s apartment was targeted, but he had taken shelter at his mother’s house the night prior. FBI agents made their way to her home in search of Brown and his laptops, which she had placed in a kitchen cabinet. Brown claims that his alleged threats against a federal officer – as laid out in the first indictment, issued several months later in September – stem from personal frustration over continued FBI harassment of his mother following the raid. On 9 November 2013, Brown’s mother was sentenced to six months probation after pleading guilty to obstruction of justice for helping him hide the laptops – the same charges levelled at Brown in the third indictment.

As listed in the search warrant for the initial raid, three of the nine records to be seized related to military and intelligence contractors that ProjectPM was investigating – one of which was never the victim of a hack. Another concerned ProjectPM itself. The government has never formally asserted that Brown participated in any hacks, raising the question of whether a confidential informant was central to providing the evidence used against him for the search warrant.

“This FBI probe was all about his investigative journalism, and his sources, from the very beginning,” Gallagher says. “This cannot be in doubt.”

In related court filings, the government denies ever using information from an informant when applying for search or arrest warrants for Brown.

But on the day of the raids, the Justice Department announced that six people had been charged in connection to the crimes listed in Brown’s search warrant. One, Hector Xavier Monsegur (aka “Sabu”), had been arrested in June 2011 and subsequently pleaded guilty in exchange for cooperation with the government. According to the indictment, Sabu proved crucial to the FBI’s investigation of Anonymous.

In a speech delivered at Fordham University on 8 August 2013, FBI Director Robert Mueller gave the first official commentary on Sabu’s assistance to the bureau. “[Sabu’s] cooperation helped us to build cases that led to the arrest of six other hackers linked to groups such as Anonymous,” he stated. Presuming that the director’s remarks were accurate, was Brown the mislabeled “other hacker” caught with the help of Sabu?

Several people have implicated Sabu in attempts at entrapment during his time as an FBI informant. Under the direction of the FBI, the government has conceded that he had foreknowledge of the Stratfor hack and instructed his Anonymous colleagues to upload the pilfered data to an FBI server. Sabu then attempted to sell the information to WikiLeaks – whose editor-in-chief, Julian Assange, remains holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London after refusing extradition to Sweden for questioning in a sexual assault case. Assange claims he is doing so because he fears being transferred to American custody in relation to a sealed grand jury investigation of WikiLeaks that remains ongoing. Though Sabu’s offer was rebuffed, any evidence linking Assange to criminal hacks on US soil would have greatly strengthened the case for extradition. It was only then that the Stratfor data was made public on the internet.

During his sentencing hearing on 15 November 2013, convicted Stratfor hacker Jeremy Hammond stated that Sabu instigated and oversaw the majority of Anonymous hacks with which Hammond was affiliated, including Stratfor: “On 4 December, 2011, Sabu was approached by another hacker who had already broken into Stratfor’s credit card database. Sabu…then brought the hack to Antisec [an Anonymous subgroup] by inviting this hacker to our private chatroom, where he supplied download links to the full credit card database as well as the initial vulnerability access point to Stratfor’s systems.”

Hammond also asserted that, under the direction of Sabu, he was told to hack into thousands of domains belonging to foreign governments. The court redacted this portion of his statement, though copies of a nearly identical one written by Hammond months earlier surfaced online, naming the targets: “These intrusions took place in January/February of 2012 and affected over 2000 domains, including numerous foreign government websites in Brazil, Turkey, Syria, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Nigeria, Iran, Slovenia, Greece, Pakistan, and others. A few of the compromised websites that I recollect include the official website of the Governor of Puerto Rico, the Internal Affairs Division of the Military Police of Brazil, the Official Website of the Crown Prince of Kuwait, the Tax Department of Turkey, the Iranian Academic Center for Education and Cultural Research, the Polish Embassy in the UK, and the Ministry of Electricity of Iraq. Sabu also infiltrated a group of hackers that had access to hundreds of Syrian systems including government institutions, banks, and ISPs.”

Nadim Kobeissi, a developer of the secure communication software Cryptocat, has levelled similar entrapment charges against Sabu. “[He] repeatedly encouraged me to work with him,” Kobeissi wrote on Twitter following news of Sabu’s cooperation with the FBI. “Please be careful of anyone ever suggesting illegal activity.”

While Brown has never claimed that Sabu instructed him to break the law, the presence of “persons known and unknown to the Grand Jury,” and whatever information they may have provided, continue to loom over the case. Sabu’s sentencing has been delayed without explanation a handful of times, raising suspicions that his work as an informant continues in ongoing federal investigations or prosecutions. The affidavit containing the evidence for the March 2012 raid on Brown’s home remains under seal.

In comments to the media immediately following the raid, Brown seemed unfazed by the accusation that he was involved with criminal activity. “I haven’t been charged with anything at this point,” he said at the time. “I suspect that the FBI is working off of incorrect information.”

This article was posted on March 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

London, 28 February 2014

Mr. Alvaro Sanchez,

Charge dAffaires, Embassy of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela in the United Kindgom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland,

Index on Censorship, an international organisation that promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression, is writing to you to show our concern for the serious violations of human rights which have been happening in Venezuela, in particular, violations of freedom of expression.

According to the information we have received, during public protests that started 12 February 2014, there have been many threats and attacks against journalists and reporters who were reporting on the demonstrations. Some of these public protests are being repressed in violent ways, with many deaths, people being injured, tortured and arbitrarily detained. In most of these cases, the attackers are police officers, members of the armed forces or civil armed groups supporting the government.

Also, most of the national media have not been publishing information about protests and violent and irregular situations, due to governmental pressure and the fear of retaliation. Over the last few years, the National Commission on Telecommunications (CONATEL) has been developing a policy of vigilance and punishment against media that do not keep an editorial line that is favourable to the government. Recently, on 11 February of this year, the General Director of CONATEL, William Castillo, criticised the media coverage of the violence by some outlets, classifying the content as hate speech and stating that those media outlets would be sanctioned. This current environment is making it difficult for the media to freely transmit information about what is happening.

The independent press has been seriously affected by the lack of foreign currency they need to acquire paper and other essential supplies for printing. Due to the monetary exchange control that exists in Venezuela, several special authorisations are required in order to legally buy foreign currency. The government has set up many obstacles that impede the independent press obtaining foreign currency for buying necessary supplies. This has caused the temporary closure of at least nine papers and problems with circulation, page reduction, edition reductions and print run reduction of at least 22 publications.

The national government has ordered, in authoritarian manner and with no judicial process, that the television channel NTN24 be taken off the air and not shown on cable television. NTN24, a Colombian news station, was one of the few media outlets that were independently transmitting news about public protests. Moreover, the government ordered the blocking of the NTN24 website from Venezuela. The government has also arbitrarily blocked the access to images on Twitter and other similar restrictions in the Internet. Additionally, the government threatened CNN en Español with censorship by prohibiting its broadcast on Venezuelan cable television services. These kinds of international media and social networks are an essential source of information for Venezuelans, due to the censorship of the national media.

All these political decisions lead to a serious problem in the field of freedom of expression and information, with every decision reducing the space for expression and increasing repression for dissenting voices. These problems are made worse in a context of high political tension and serious repression from government employees.

Consequently, we demand that the Venezuelan government show respect for human rights in Venezuela, particularly the right of freedom of expression, and in this sense, should:

1. Stop the threats and attacks against journalists and media.

2. Allow national and international media to freely spread information, including information that criticises the government, without fear of repression from any governmental organisation.

3. Facilitate the procedures for the acquisition of foreign currency by the independent print media, so that they can buy paper and other essential supplies needed for the publications.

Sincerely,

Rachael Jolley

Index on Censorship