Contents – Whistleblowers: the lifeblood of democracy

Index’s new issue of the magazine looks at the importance of whistleblowers in upholding our democracies.

Featured are stories such as the case of Reality Winner, written by her sister Brittany. Despite being released from prison, the former intelligence analyst is still unable to speak out after she revealed documents that showed attempted Russian interference in US elections.

Playwright Tom Stoppard speaks to Sarah Sands about his life and new play title ‘Leopoldstatd’ and, 50 years on from the Pentagon Papers, the “original whistleblower” Daniel Ellsberg speaks to Index .

Features

Holding the rich and powerful to account by Martin Bright: We look at key whistleblower cases around the world and why they matter for free speech

The Index: Free expression round the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern

Why journalists need emergency safe havens by Rachael Jolley: Legal experts including Amal Clooney have called for a new type of visa to protect journalists

Spinning bomb by Nerma Jelacic: Disinformation and the assault on truth in Syria learned its lessons from the war in Bosnia

Identically bad by Helen Fortescue: Two generations of photojournalists document the political upheaval shaping Belarus 30 years apart

Always looking over our shoulders by Henry McDonald: Across the sectarian divide in Northern Ireland again, journalists are facing increasing threats

Crossing red lines by Fréderike Geerdink: The power struggle between the PUK and KDP is bad news for press freedom in Kurdistan

Cartoon by Ben Jennings: The reptaphile elite are taking over! So say the conspiracy theorists, anyway

People first but not the media by Issa Sikiti da Silva: There was hope for press freedom when Felix Tshisekedi took power in DR Congo, but that is now dwindling

Controlling the Covid message by Danish Raza and Somak Ghoshal: Covid-19 has crippled the Indian health service, but the government is more concerned with avoiding criticism

Special Report

Reality Winner. Credit: Michael Holahan/The Augusta ChronicleSpeaking for my silenced sister by Brittany Winner: Meet Reality Winner, the whistleblower still unable to speak out despite being released from prison

Feeding the machine by Mark Frary: Alexei Navalny has been on hunger strike in a penal colony outside Moscow, since his sentencing. Index publishes his writings from prison

An ancient virtue by Ian Foxley: A whistleblower explains the ancient Greek idea of parrhesia that is at the core of the whistleblower principle

Truthteller by Kaya Genç: Journalist Faruk Bildirici tells Index how one of Turkey’s most respected newspapers became an ally of Islamists

The price of revealing oil’s dirty secrets: Whistleblower Jonathan Taylor has been hounded since revealing serious cases of bribery within the oil industry

The original whistleblower: 50 years on from the Pentagon Papers, whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg speaks to Index

Fishrot, the global stench of scandal: Former Samherji employee Johannes Stefansson exposed corruption and the plundering of Namibian fish stocks

Comment

What is a woman? by Kathleen Stock and This is hate, not debate by Phoenix Andrews: Two experts debate the case of Maya Forstater, in which Index legally intervened, and if the matter is a case of hate speech

Battle cries by Abbad Yahya: The lost voice of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

A nightmare you can’t wake up from by Nandar: A feminist activist forced to flee her home country after the military coup in February

Trolled by the president by Michela Wrong: Rwanda’s leader Paul Kagame is known for attacking journalists. What is it like to incur his wrath?

When the boot is on the other foot by Ruth Smeeth: People must fight not only for their own rights, but for the free speech of the people they do not agree with

Culture

Playwright Tom Stoppard. Credit: Liba Taylor/Alamy Stock Photo

Uncancelled by Sarah Sands: An interview with the playwright Sir Tom Stoppard on his new play, Leopoldstadt, and the inspiration behind it

No light at the end of the tunnel by Benjamin Lynch: Yemeni writer Bushra al-Maqtari provides us with an exclusive extract of her award-winning novel, Behind the Sun

Dead poets’ society by Mark Frary: The military in Myanmar is targeting dissenting voices. Poets were among the first to be killed

Politics or passion? by Mark Glanville: Contemporary poet Stanley Moss on his long-standing love for China

Are we becoming Hungary-lite? by Jolyon Rubinstein: Comedian Jolyon Rubinstein on the death of satire

Editor’s letter: All hail those who speak out

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The brave stand up when others are afraid to do so. Let’s remember how hard that is to do, says Rachael Jolley in the autumn 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.”][vc_column_text]

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.

The US Supreme Court justice may be a popular icon right now, but when she set her course to be a lawyer she was in a definite minority.

For many years she was the only woman on the court bench, and she was prepared to be a solitary voice when she felt it was vital to do so, and others strongly disagreed.

The dissenting voice and its place in US law is a fascinating subject. A justice on the court who disagrees with the majority verdict publishes a view about why the decision is incorrect. Sometimes, over decades, it becomes clear that the individual who didn’t go with the crowd was right.

The dissenting voice, it seems, can be wise beyond the established norms. By setting out a dissenting opinion, it gives posterity the chance to reassess, and perhaps to use those arguments to redraft the law in later times.

Bader Ginsburg was the dissenting voice in the case of Ledbetter v Goodyear – in which Lily Ledbetter brought a case on pay discrimination but the court ruled against her – and in Shelby County v Holder on voting discrimination, an issue likely to be hotly debated again in this year’s US presidential election. Bader Ginsburg’s opinions may not have been in the majority when those cases were heard but the passage of time, and of some legislation, proved her right.

The dissenting voice in law is a model for why freedom of expression is so vital in life. You may feel alone in your fight for the right to change something (or in your position on why something is wrong), but you must have the right to express that opinion. And others must be willing to accept that minority views should be heard – even if they disagree with them.

Fight for the principle, and when the time comes that you, your friends or your neighbours need it, it will be there for you.

Right now, writers, artists and activists are standing up for that principle, not necessarily for themselves but because they feel it is right.

Sometimes they also bravely dissent when most people are afraid to speak up for change, or to disagree with those who shout the loudest.

Being different and on the outside is a lonely place to be, but the pressure is even greater when you know opposing an idea, or law, could mean losing your home or your job, or even landing in prison.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd0d0d”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The dissenting voice in law is a model for why freedom of expression is so vital in life.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As editor-in-chief at Index I have been privileged to work with extraordinary people who are willing to be dissenting voices when, all around them, society suggests they should be quiet. They smuggle out words because they think words make a difference. They choose to publish journalism and challenging fiction because they want the world to know what is going on in their countries. They often take enormous risks to do this.

For them, freedom of expression is essential. Murad Subay is a softly spoken Yemeni artist with a passion for pizza. He produced street art even as the bombs fell around him in Sana’a. Often called Yemen’s Banksy, Subay – an Index award winner – worked under unbelievably horrible conditions to create art with a message.

In an interview with Index in 2017, Subay told us: “It’s very harsh to see people every day looking for anything to eat from garbage, waiting along with children in rows to get water from the public containers in the streets, or the ever-increasing number of beggars in the streets. They are exhausted, as if it’s not enough that they had to go through all of the ugliness brought upon them by the war.”

Dissenting voices come from all directions and from all around the world.

From the incredibly strong Zaheena Rasheed, former editor of the Maldives Independent, who was forced to leave her country because of death threats, to regular correspondence from our contributing editor in Turkey, Kaya Genç, these are journalists who keep going against the odds. These are the dissenting voices who stand with Bader Ginsburg.

Over the years, the magazine has featured many writers who have stood up against the crowd. People such as Ahmet Altan, whose words were smuggled out of prison to us. He told us: “Tell readers that their existence gives thousands of people in prison like me the strength to go on.”

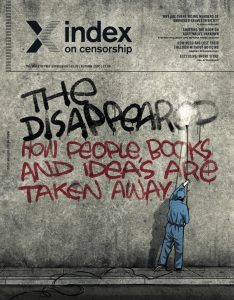

In this issue, we explore those whose ideas and voices – and sometimes, horrifically, bodies – are deliberately disappeared to muffle their dissent, or even their very existence.

Many people associate the term “the disappeared” with Argentina during the dictatorships, where we know about some of the horrific tactics used by the junta. Opposition figures were killed; newborn babies were taken from their mothers and given to couples who supported the government, their mothers murdered and, in many cases, dumped at sea to get rid of the evidence. The grandmothers of those who were disappeared are still fighting to bring attention to those cases, to uncover what happened and to try to trace their grandchildren using DNA tests.

Index published some of those stories from Argentina at the time because Andrew Graham-Yooll, who was later to become the editor at Index, smuggled out some of the information to us and to The Daily Telegraph, risking his life to do so.

We explore what and who are being disappeared by authorities that don’t want to acknowledge their existence.

Thousands of people who are escaping war and starvation try to flee across the Mediterranean Sea: hundreds disappear there. Their bodies may never be found.

It is convenient for the authorities on both sides of the sea that the numbers appear lower than they really are and the real stories don’t get out.

In a special report for this issue, Alessio Perrone reveals the tactics being used to cover up the numbers and make it appear there are fewer journeys and deaths than in reality.

The International Organisation for Migration’s Missing Migrants Project says that 20,000 people have died in the Mediterranean since records began in 2014, but many say this is an underestimation.

Certainly there are unmarked graves in Sicily where bodies have been recovered but no one knows their names (see page 30). The Italian government has, as we have previously reported, used deliberate tactics to make it harder to report on the situation and to stop the rescue boats finding refugees adrift near her boundaries.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#2a31b7″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”It is convenient for the authorities on both sides of the sea that the numbers appear lower than they really are and the real stories don’t get out.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Also in this issue, Stefano Pozzebon and Morena Joachín report on how Guatemala’s national police archives – which house information on those people who were disappeared during the civil war – is currently closed, and not for Covid-19 reasons (see page 27).

Fifteen years after the archive was first opened to the public, a combination of political pressure and a desire to rewrite history in the troubled nation has closed it. This is a tragedy for families still using it in an attempt to trace what happened to their families.

In Azerbaijan (see page 8), another tactic is being used to silence people – this time using technology. Activists are having their profiles hacked on social media and then posts and messages are being written by the hackers and posted under their names.

Their real identities conveniently disappear under a welter of false information – a tactic used to undermine trust in journalists and activists who dare to challenge the government so that the public might stop believing what they write or say.

This is my 30th and final issue of the magazine after seven years as editor (although I will still be a contributing editor), and it is another gripping one.

They smuggle out words because they think words make a difference.

Over the years, I am proud to have worked with the incredible, brave, talented and determined. We have published new writing by Ian Rankin, Ariel Dorfman, Xinran, Lucien Bourjeily, and Amartya Sen, among others. And it has been a privilege to work with the mindblowing, sharp, analytical journalism from the pens of our incredible contributing editors over the years, including Kaya Genç, Irene Caselli, Natasha Joseph, Laura Silvia Battaglia, Stephen Woodman, Duncan Tucker and Jan Fox, plus regular contributors Wana Udobang, Karoline Kan, Steven Borowiec, Alessio Perrone and Andrey Arkhangelsky.

These people do amazing work: their writing is ahead of the game and they bring together thought-provoking analysis and great human stories. Thank you to all of them, and to deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld.

They have told me again and again why they value writing for Index on Censorship and the importance of its work.

And because we believe that supporting writers and journalists is also about them getting paid for their work, unlike some others we have always supported the principle of paying people for their journalism.

Over the years we have attempted to go above and beyond, providing a little extra training when we can, translating Index articles into other languages, inviting journalists we work with to events, and introducing them to book publishers.

But just like the first time I ventured into the archives of the magazine, I am still amazed by what gems we have inside. We have recently reached our biggest readership to date, with hundreds of thousands of articles being downloaded in full, showing an appetite for the kind of journalism and exclusive fiction we publish.

Thank you, readers, for being part of the journey, and please continue to support this small but important magazine as it continues to speak for freedom.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is the former editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship’s autumn 2020 issue, entitled The disappeared: how people, books and ideas are taken away.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2020 magazine podcast featuring Hong Kong-based journalist Oliver Farry, who discusses the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in the region

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

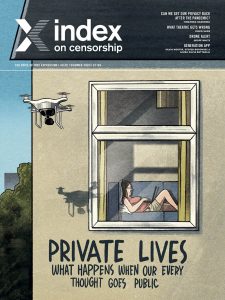

Contents – Private lives: What happens when our every thought goes public

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Katherine Parkinson, David Hare, Marina Lalovic, Geoff White and Timandra Harkness”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

In our In Focus section, we interview journalists in Serbia, Hungary and Kashmir who are trying to report the truth in places where the truth can be as dangerous, if not more, than Covid-19. And we have an interview with and poet from the playwright David Hare.

We have a very special culture section in this issue. Three playwrights have written short plays for the magazine around the theme of pandemics. V (formerly Eve Ensler), the author of The Vagina Monologues, takes you to the aftermath of a nuclear disaster; Katherine Parkinson of The IT Crowd writes about online dating during quarantine; Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily is inspired by recent events in his country in his chilling look at protest right now.

Buy a copy of the magazine from our online store here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][vc_column_text]

Virus masks a different threat by Hannah Leung and Jemimah Steinfeld: China is using Covid-19 responses and Hong Kong’s new security law to reduce freedoms in the city state

Back-up plan by Timandra Harkness: Don’t blindly give away more freedoms than you sign up for in the name of tackling the epidemic. They’re hard to reclaim

The eyes of the storm by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Spies are on the streets of Uganda making sure everyone abides by Covid-19 rules. They’re spying on political opposition too. A dispatch from Kampala

Generation app by Silvia Nortes, Steven Borowiec and Laura Silvia Battaglia: How do different generations feel about sharing personal data in order to tackle Covid-19? We ask people in South Korea, Spain and Italy

Zooming in on privacy concerns by Adam Aiken: Video app Zoom is surging in popularity. In our rush to stay connected, we need to make security checks and not reveal more than we think

Seeing what’s around the corner by Richard Wingfield: Facial recognition technology may be used to create immunity “passports” and other ways of tracking our health status. Are we watching?

Don’t just drone on by Geoff White: If drones are being used to spy on people breaking quarantine rules, what else could they be used for? We investigate

Sending a red signal by Tianyu M Fang: When a contact tracing app went wrong a journalist was forced to stay in their home in China

The not so secret garden by Tom Hodgkinson: Better think twice before bathing naked in the backyard. It’s not just your neighbours that might be watching you. Where next for privacy?

Hackers paradise by Stephen Woodman: Hackers across Latin America are taking advantage of the current crisis to access people’s personal data. If not protected it could spell disaster

Italy’s bad internet connection by Alessio Perrone: Italians have one of the lowest levels of digital skills in Europe and are struggling to understand implications of the new pandemic world

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: Ping! Don’t forget we’re watching you… everywhere

Less than social media by Stefano Pozzebon: El Salvador’s new leader takes a leaf out of the Trump playbook to use Twitter to crush freedoms

Nowhere left to hide by Kaya Genç: Privacy has been eroded in Turkey for many years now. People fear that tackling Covid-19 might take away their last private free space

Open book? by Somak Ghoshal: In India, where people are forced to download a tracking app to get paid, journalists are worried about it also being used to access their contacts

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Knife-edge politics by Marina Lalovic: An interview with Serbian journalist Ana Lalic, who forced the Serbian government to do a U-Turn

Stage right (and wrong) by Jemimah Steinfeld: The playwright David Hare talks to Index about a very 21st century form of censorship on the stage. Plus a poem of Hare’s published for the first time

Inside story: Hungary’s media silence by Viktória Serdült: What’s it like working as a journalist under the new rules introduced by Hungary’s Viktor Orbán? How hard is it to report?

Life under lockdown: A Kashmiri Journalist by Bilal Hussain: A Kashmiri journalist speaks about the difficulties – personal and professional – of living in the state with an internet shutdown during lockdown

The truth will out by John Lloyd: Journalists need to challenge themselves and fight for media freedoms that are being eroded by autocrats and tech companies

Extremists use virus to curb opposition by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Covid-19 is being used by religious militia as a recruitment tool in Yemen and Iraq. Speaking out as a secular voice is even more challenging

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Masking the truth by V: The writer of The Vagina Monologues (formerly known as Eve Ensler) speaks to Index about attacks on the truth. Plus a new version of her play about living in a nuclear wasteland

Time out by Katherine Parkinson: The star of The IT Crowd discusses online dating and introduces her new play, written for Index, that looks at love and deception online

Life in action by Lucien Bourjeily: The Lebanese director talks to Index about how police brutality has increased in his country and how that informed the story of his new play, published here for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]

Putting abuse on the map by Orna Herr: The coronavirus crisis has seen a huge rise in media attacks. Index has launched a map to track these

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Forced out of the closet by Jemimah Steinfeld: As people live out more of their lives online right now, our report highlights how LGBTQ dating apps can put people’s lives at risk

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Yemeni artist Thiyazen Al-Alawi uses his craft to shed light on the destructive situation in Yemen through street art campaigns. He hopes to inform the public of what the war has done to his homeland.

Yemeni artist Thiyazen Al-Alawi uses his craft to shed light on the destructive situation in Yemen through street art campaigns. He hopes to inform the public of what the war has done to his homeland. Moe Moussa is a journalist, podcaster, poet, and the founder of the Gaza Poet Society. He uses various forums and mediums to amplify the voices of Palestinians.

Moe Moussa is a journalist, podcaster, poet, and the founder of the Gaza Poet Society. He uses various forums and mediums to amplify the voices of Palestinians. Fatoş İrwen is a Kurdish artist and teacher from Diyarbakır, Turkey working with a variety of materials and techniques.

Fatoş İrwen is a Kurdish artist and teacher from Diyarbakır, Turkey working with a variety of materials and techniques. Hamlet Lavastida has been described as a political activist by way of art. Lavastida uses his art to document human rights abuses in Cuba and to criticise Cuban authorities.

Hamlet Lavastida has been described as a political activist by way of art. Lavastida uses his art to document human rights abuses in Cuba and to criticise Cuban authorities.