7 Jul 2017 | Asia and Pacific, China, Digital Freedom, News and features

Update: On 13 July 2017 the Chinese Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, jailed for his pro-democracy work, died in hospital aged 61.

When Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, Chinese authorities were sent into a state of panic. Liu had been in prison since 2009, following the release of Charter 08, a pamphlet he co-wrote that called for greater democratic freedoms. As the world’s attention was on China and on Liu, all references to Liu and the prize were blocked online and off. Then his wife and many of his acquaintances were detained in an attempt to stop them from going to Oslo and collecting it on his behalf. At the ceremony itself, an empty chair became a stark reminder of his absence and soon the words “empty chair” started to race through the internet. These too were blocked.

Liu has since remained in prison and efforts to stamp out his name continue. But last week he once again made headlines following his release from prison on health grounds. At the time of writing, reports say Liu, who is suffering from late-stage liver cancer, is close to death. For free speech advocates around the world, this news is saddening. No figure has come to represent the fight for Chinese democracy as much as Liu Xiaobo.

Born in 1955 in Jilin province in northeast China, the son of two teachers, Liu went on to become a writer, activist and academic. It was while teaching at Columbia’s Barnard College in New York in 1989 that the Tiananmen Square protests broke out. Liu decided to return to China to take part in them on their final, fateful day. This led to his arrest and imprisonment, the first of four times.

Liu was shunned by China’s academic community when he left prison two years later, but that did not silence him and he continued to build on his reputation within China as an outspoken critic of the Communist Party. He also started a tradition of writing poems about Tiananmen every year to mark the anniversary – a powerful reminder that the government does not have a monopoly on memory.

For Liu the internet was a lifeline. He described it as “God’s gift to the Chinese people” in an essay that was published in Index on Censorship magazine in 2006. The web became his primary portal to publish his thoughts to the outside world and to reach audiences when traditional forms of media were out of bounds. Liu wrote that “the effect of the internet in improving the state of free expression in China cannot be underestimated”.

Liu’s influence peaked in December 2008 with Charter 08, a document modelled on Václav Havel’s Charter 77, written in Communist Czechoslovakia 30 years earlier. The document outlines the basic principles and fundamental rights that should govern China’s political landscape. Over 350 intellectuals and activists initially signed it, with a further 10,000 people including academics, journalists and businessmen adding their names to it upon its released. The government’s reaction to Charter 08 was swift and harsh. Liu was initially arrested two days prior to its official publication and later charged with 11 years in prison for incitement to subversion, during a trial in which he said he had no enemies. Index has repeatedly called for his release.

Isabel Hilton, a leading expert on China, told Index back in 2010 that “when the history of free expression and freedom of ideas is written, he and the other signatories of Charter 08 will be remembered as courageous citizens who sought the best for their country”.

In an interview Liu gave prior to his arrest, he said: “The way I see it, people like me live in two prisons in China. You come out of the small, fenced-in prison, only to enter the bigger, fenceless prison of society.” Since Liu’s arrest almost a decade ago, China has continued to change at breakneck speed. When it comes to human rights and free speech, sadly this change has been predominantly for the worse. The bigger, fenceless prison that Liu spoke of is today a lot more closed and draconian. China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, has overseen a huge crackdown on dissent. And the internet, God’s gift to China, is more regulated that ever before. Even seemingly innocent entertainment channels are frequently shut down, such as Kuaishou, a video-sharing site, which Index on Censorship reported on in its most recent issue.

Despite this, people continue to fight for greater freedom and rights in China, exploiting loopholes online as and when they can, and showing remarkable courage in the face of extreme adversity. The role of Liu in setting an example and providing inspiration cannot be underplayed. Liu’s Nobel chair might still be empty, but he is never forgotten, nor will he ever be.

Read more:

Liu Xiaobo’s article on the power of the internet in full

A poem by Liu translated for Index on Censorship magazine

Esteemed writer Ma Jian’s response to the Nobel Peace Prize and thoughts on Liu

The government ban of words related to Liu Xiaobo and the Nobel Peace Prize

14 Feb 2017 | Magazine

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” full_height=”yes” columns_placement=”stretch” equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1594032073955{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/magazine-art-1460×490.png?id=80524) !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Shakespearean actress Janet Suzman said about our special Shakespeare 400 issue: “From every corner of the unfree world the essays you have printed bear me out; theatre is a danger to ignorance and autocracy and Shakespeare still holds the sway. I congratulate you and Index on giving such space to a writer who is still bannable after 400 plus years.”” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A quarterly magazine set up in 1972, Index has published oppressed writers and refused to be silenced across 252 issues.

The brainchild of the poet Stephen Spender, and translator Michael Scammell, the magazine’s very first issue included a never-before-published poem, written while serving a sentence in a labour camp, by the Nobel Prize-winning Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

The magazine continued to be a thorn in the side of Soviet censors, but its scope was far wider. From the beginning, Index declared its mission to stand up for free expression as a fundamental human right for people everywhere – it was particularly vocal in its coverage of the oppressive military regimes of southern Europe and Latin America, but was also clear that freedom of expression was not only a problem in faraway dictatorships. The winter 1979 issue, for example, reported on a controversy in the United States in which the Public Broadcasting Service had heavily edited a documentary about racism in Britain, and then gone to court attempting to prevent screenings of the original version.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”An archive of past battles won, and a beacon of present and future struggles. It’s unique brand of practical, practising advocacy is as necessary as ever.” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23dd3333″ google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Index stood firmly against the apartheid regime. South African Nadine Gordimer, yet another Nobel prize-winning author, wrote regularly for the magazine. Big names from around the literary world flocked to contribute to the magazine, often before their struggles had brought internal accolade – a single issue in 1983 included the exiled Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, later a Nobel prize winner, and Czechoslovakian dissident Vaclav Havel, who went on to be his country’s last president before it split into Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Kurt Vonnegut and Arthur Miller were also among the more famous bylines. Salman Rushdie, the author at the centre of the Satanic Verses controversy, was frequently featured on Index’s pages while there was a bounty offered for his murder by the Iranian government.

After the fall of communism, there was a widespread misconception that censorship was “over”, but journalists, authors and dissidents have continually reached out to Index when squeezed. The Russian reporter Anna Politkovskaya wrote in 2002 of the threats made against her life when she began investigating Russia’s war in Chechnya, four years before she was assassinated in Moscow.

After more than 40 years, Index continues to stand with the silenced all over the world. In October 2016, the Times Literary Supplement described it as “an archive of past battles won, and a beacon of present and future struggles. It’s unique brand of practical, practising advocacy is as necessary as ever.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Words: Kieran Etoria-King[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support Index” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F12%2Ffashion-rules%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

In times of extraordinary crisis, governments often take the opportunity to roll back on personal freedoms and media freedom.

Will you join with others from around the world who have concerns about restrictions on freedoms to support our work?

DONATE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”113840″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/12/fashion-rules/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The world’s most important writers. In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

DONATE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”113840″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/12/fashion-rules/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The world’s most important writers. In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Apr 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016 Extras

Order your copy of the spring issue of Index on Censorship here.

Saturday 23 April marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. The Bard’s work has long been used to tackle difficult or controversial issues; issues that most often only received an audience due to the cloak of his respectability. To honour the occasion Index has put together a list of all things Shakespeare.

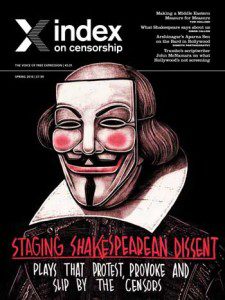

Shakespeare and his role in protest and dissent is the theme of the spring 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine: Staging Shakespearean Dissent; Plays That Protest, Provoke and Slip by the Censors. The issue features pieces that explore how the bard’s plays have been used to circumvent censorship and tackle difficult issues around the world; from Bollywood adaptions to Othello in apartheid-era South Africa and a ground-breaking recent performance of Romeo and Juliet between Kosovan and Serbian theatres, along with reports on theatre upsetting people in the USA, and interviews with directors around the world

Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley introduces our Shakespeare special issue with her editorial piece, How Shakespeare’s plays smuggle protest. In this piece Jolley discusses how the work of “established” or “historic” playwrights gave actors the chance to tackle themes that would otherwise never be allowed.

Shakespeare was no stranger to censorship, from the Elizabethan to Jacobean police states. In this extract actor and theatre director Simon Callow looks at how his plays amused monarchs and dictators but also prompted their anger.

My Mate Shakespeare recasts the playwright as a brandy loving bingo addict, struggling in a war zone. The poem, which was published in the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, was written by poet Edin Suljic following a visit to his home country, Former Yugoslavia. The issue also features an interview with the poet, who fled to London in 1991 ahead of the country’s impending war, discussing his inspiration for the poem and his involvement with theatre group Bards Without Borders.

How well do you know Shakespeare? Take our quiz and see how much you know about the Bard and his work.

The theatre and censorship reading list is a compilation of articles from the magazine archive covering theatre censorship across the world. From the censorship of Romeo and Juliet in US high school textbooks to Janet Suzman’s controversial production of Othello in apartheid-era South Africa, to the banning of performances of Macbeth in actors’ homes in Czechoslovakia.

In an interview with magazine editor Rachael Jolley an award-winning cartoonist, Ben Jennings, discusses his design for the latest Index on Censorship magazine cover on the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death.

Hitler was a Shakespeare fan; Stalin feared Hamlet; Othello broke ground in apartheid-era South Africa; and Brazil’s current political crisis can be reflected by Julius Caesar. Across the world different Shakespearean plays have different significance and power. In our global guide to using Shakespeare to battle power some of our writers talk about some of the most controversial performances and their consequences.

Order your full-colour print copy of our Shakespeare magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.