24 Sep 2024 | News and features

This afternoon, the president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Masoud Pezeshkian, will address world leaders at the United Nations General Assembly. He left Tehran for New York on Sunday, reportedly accompanied by a large delegation of 40 people, including close family members.

Pezeshkian’s trip to New York comes as renowned rapper and human rights activist Toomaj Salehi remains in prison in Iran despite widespread international condemnation. Salehi’s music and activism have supported the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in Iran, challenged corruption, and tackled human rights abuses by the Iranian authorities. In retaliation for his work, Salehi has been subjected to over three years of judicial harassment. He has been imprisoned, beaten, and tortured. In April 2024, he was sentenced to death by Branch 1 of the Isfahan Revolutionary Court for “corruption on earth,” punishable by death under the Islamic Penal Code. The death sentence was overturned by the Iranian Supreme Court in June 2024 and referred to the Revolutionary Court for sentencing. But months later, Salehi remains imprisoned — and now the authorities have charged him with fresh offences for his music and his work. The Iranian authorities continue to refuse to provide him with adequate healthcare, including treatment and pain relief for his torture-inflicted injuries.

Two Urgent Appeals have been filed with United Nations (UN) bodies. In May 2024, an Urgent Appeal was filed with two UN Special Rapporteurs by an international legal team at Doughty Street Chambers on behalf of the family of Toomaj Salehi and Index on Censorship. In July 2024, the Human Rights Foundation submitted an individual complaint to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention in Salehi’s case, in conjunction with the counsel team at Doughty Street Chambers and Index on Censorship.

Today’s Call

In advance of Pezeshkian’s speech today, Salehi’s family, his international counsel team at Doughty Street Chambers, Index on Censorship, and the Human Rights Foundation call for Iran to immediately and unconditionally release Salehi.

Salehi’s friend and manager of his social media accounts, Negin Niknaam, said: “Toomaj remains unlawfully in Dastgerd prison despite the lack of an arrest order and being in need of urgent medical care to avoid permanent disability for injuries he endured in custody under torture, which in itself is forbidden as per Article 38 of the Iranian Constitution.

“I ask UN Member States to urgently raise these concerns, remind the Islamic Republic of Iran’s authorities of the legal obligations and demand a full commitment for the immediate release of Toomaj from President Masoud Pezeshkian before his address at the United Nations General Assembly in New York.”

Salehi’s cousin, Arezou Eghbali Babadi, added: “The international community’s solidarity and support have played a key role so far in ensuring the death penalty for my cousin Toomaj Salehi was overturned. Now the international community must speak out and press the Iranian president to release Toomaj, before it is too late.”

24 Sep 2024 | News and features

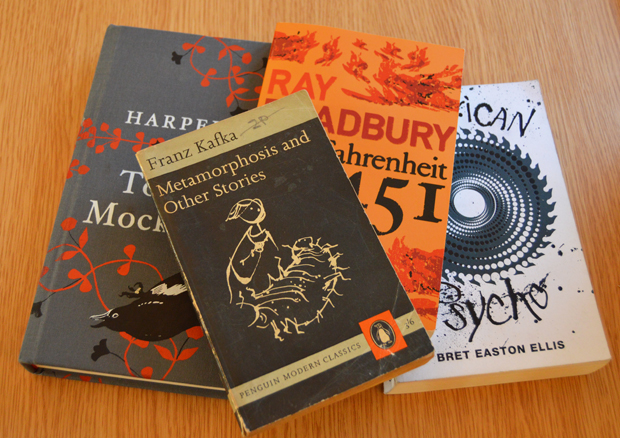

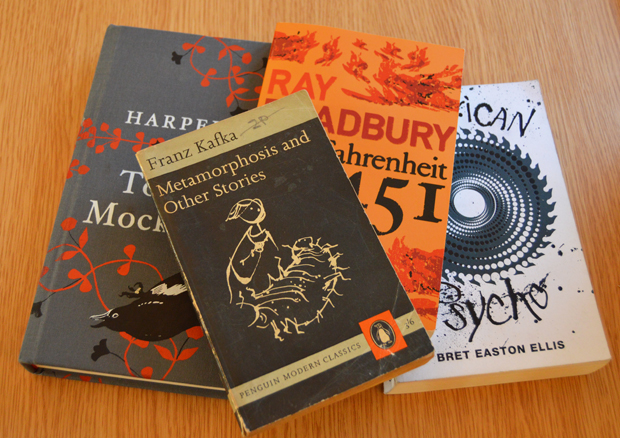

Banned Books Week is here once again. And so too are more stories of books being censored across the world. This week, Pen America reported that the number of book bans in public schools has nearly tripled in 2023-24 from the previous school year.

While the week-long Banned Books Week event, supported by a coalition including Index on Censorship, looks largely towards bans in the USA, we’re taking a moment to reflect on global censorship of literature. We asked the Index team to share what they think is the most ridiculous instance of book censorship, from the outright silly to the baffling but dangerous. Some of these examples verge on amusing — the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s aversion to talking animals, for example — but the bans that have ended in attempted murders just go to show that the practice of book banning itself is completely nonsensical, and can lead to real harm.

Banned Books (Photo by Aimée Hamilton)

Too many talking animals

You don’t have to have children to imagine what a clichéd kids book might look like. Yes, you’ve guessed right – animated animals. Tigers, mice, dogs – they’re all common in children’s literature. But the Chinese authorities have an uncomfortable relationship with our furry friends.

In 2022 a Hong Kong court sent five people to prison for publishing a series of books called Sheep Village (and of course they banned the books too). To be fair these illustrated books, aimed at kids aged four to seven, didn’t code their political messages well: a flock of sheep (stand-in for Hong Kongers) peacefully resist a savage wolf pack (the guys in Beijing). So this might not be the most absurd example, though it did feel like an absurdly low moment.

However, what was clearly absurd on all levels was the 1931 ban of Alice in Wonderland by the governor of Hunan Province. The book’s crime? Talking animals. Apparently they shouldn’t have used human language and putting humans and animals on the same level was “disastrous”. What unites the CCP with the Republic of China that came before it? Unease around anthropomorphised animals it would seem.

Too many banned books

Ban This Book by Alan Gatz, a book about book bans, has been banned by the state flying the banner for banning books. This is not a tongue twister, riddle or code. It is the crystallisation of the absurdity of banning books.

In January 2024, the book was banned in Indian River County in Florida after opposition from parents linked to Moms for Liberty. According to the Tallahassee Democrat, the school board disliked how the book “referenced other books that had been removed from schools” and accused it of “teaching rebellion of school board authority”. When you are trying to reshape the world in line with your own blinkered view it is probably best not to draw attention to it by calling out reading as an act of rebellion. Just a thought.

The book tells the story of Amy Anne Ollinger’s fight to overturn a book ban in her fictional school library. The book’s conclusion leads Amy Anne “to try to beat the book banners at their own game. Because after all, once you ban one book, you can ban them all”.

This tells us something – the self-harming absurdity of book bans is apparent to kids like Amy Anne but not to the prudish administrators and thuggish groups wielding their mob veto like a weapon. Groups like Moms for Liberty and their fellow censors obscure the darkness of our shared history by removing any reference to it and by pretending it did not happen — not by addressing the root causes or working to ensure it does not happen again.

- Nik Williams, policy and campaigns officer

Too Belarusian

In Belarus, numerous books in the Belarusian language by the country’s best classical and modern writers have been banned, especially following the 2020 presidential election and pro-democracy protests. Unbelievably, Lukashenka’s regime — often called the last dictatorship in Europe and backed by Russia — views Belarusian historical, cultural and national identity as a threat.

Many books in Belarusian have been labelled extremist and even destroyed from the National Library’s collection since the protests started in August 2020. This includes Dogs of Europe by Alhierd Baharevich, works by 19th century writer Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievich and 20th century poet Larysa Hienijush, among others.

- Jana Paliashchuk, researcher on Index’s Letters from Lukashenka’s Prisoners project

Too decadent and despairing

Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, possibly the greatest short story ever written, was banned by both the Nazis and the Soviets. Being a Jewish author, the Nazis burned Kafka’s books on their “sauberen” (cleansing) pyres. But in the Soviet Union, his books were banned as “decadent and despairing”. This was clearly a judgement made by officials without much knowledge of the history of the novel, where so many titles are filled with human despair. Without these, we would not get the contrasting light of decadent writers like Oscar Wilde and JK Huysmans.

- David Sewell, finance director

Too mermaidy

One of my favourite books to read with my son is Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love. It’s a beautiful picture book where a young boy dreams of becoming a mermaid after seeing a school / pod (collective noun to be determined) of merfolk on the way to the Coney Island Mermaid Parade, then rummages around his nana’s home for a costume.

In various parts of the USA, Julian has been banned. In a school district in Iowa, it was flagged for removal under a law that “bans books that depict or describe sex acts”, which apparently also covers gender identity — there are definitely no sex acts in this book. In other districts, it’s been fully banned due to representing the LGBTQ+ community.

If book banners in the USA are really worried about kids becoming mermaids, then I’d like to know on what grounds. Because, quite frankly, I always wanted to be a mermaid, and if it turns out it was a viable option, I have some regrets. Personally, I’d be more concerned about Julian ripping down his nana’s curtains to make a tail, à la Julie Andrews making costumes for the Von Trapp children.

- Katie Dancey-Downs, assistant editor

Too accurate

In Egypt, Metro, the country’s first graphic novel by Magdy El Shafee, was quickly banned after publication in 2008 for “offending public morals”. This was likely due to the novel’s depiction of a half-naked woman, inclusion of swear words and general portrayal of poverty and corruption in Egypt during the former president Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule. The author was charged under article 178 of the Egyptian penal code for infringing “upon public decency” and fined 5,000 LE. It was eventually republished in Arabic in 2012.

- Georgia Beeston, communications and events manager

Too dystopian

Aldous Huxley’s 1932 dystopian classic Brave New World explores an imagined future centred on productivity and enforced “happiness” at the expense of individual freedom. Set in 2540, society has been stripped of families, with babies manufactured synthetically with specific characteristics, then forced into a predetermined “caste” system. People are encouraged to prioritise short-term gratification through casual sex and taking a “happiness” drug called soma, making them blissfully unaware of their imprisonment within the system.

Since its publication nearly 100 years ago, the novel has caused controversy globally. It was initially banned in Ireland and Australia in 1932 for eschewing traditional familial and religious values, then later banned in India in 1967 for its sexual content, with Huxley even being referred to as a “pornographer” for depicting a society that encourages recreational sex. It is still banned in many classrooms and libraries across America for a range of wild reasons, from use of offensive language and sexual explicitness to racism and “conflict with a religious viewpoint”.

But Huxley’s imagined future is one of horror. He uses themes of enforced, unfettered pleasure and a twisted genetic-based class system to express how humans’ complex problems and moral quandaries cannot be solved by scientific advancement alone. The main point of dystopian fiction is to tell a cautionary tale of the levels of exploitation that society could sink to, in order to save the world at large. While it was undoubtedly shocking and crass for its time, the fact that Huxley’s novel still ruffles feathers reveals a complete misunderstanding of allegory.

Too many lesbians

I first read Radclyffe Hall’s legendary lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness, published in 1928, with bated breath as a young, closeted queer person. Her portrayal of young woman ‘Stephen’ Gordon and her romance with Mary Llewellyn was wildly liberating and satisfying to read. Of course, as a product of its time it is in many ways outdated and of course laced with problematic values, for example biphobia and misogyny. But it was hugely important in terms of normalising queer relationships over a century ago.

Shortly after publication, the book went to trial in Britain on the grounds of “obscenity” and was subsequently banned — but this is no Lady Chatterley’s Lover. There are no real ‘hot under the collar moments’. The only ‘obscenity’ was the portrayal of two women in a romantic relationship, even though (unlike male homosexuality), lesbianism wasn’t actually illegal in 1928.

- Anna Millward, development officer

Too friendly

The award-winning writer and painter Leo Lionni’s first children’s book Little Blue and Little Yellow (1959) is a short story for young children about two best friends who, one day, can’t find each other. When they meet again, they give each other such a big hug that they turn green.

Despite its important message about the power of love and friendship, the mayor of Venice decided to ban it from all preschools in the province for “undermining traditional family values”. It was one of more than 50 children’s books to have been banned just days after he took up the post after his election in 2015.

- Jessica Ní Mhainín, head of policy and campaigns

Too uncensored

As ironies go, the banning of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 may be the strangest. The novel describes a dystopian future in which books are banned and “firemen” burn any that are found – its title comes from the ignition temperature of paper.

In 1967, a new edition of the book aimed at high schools, known as the Bal-Hi edition, was substantially altered to remove swear words and references to drug use, nudity and drunkenness. Somehow, the censored text came to be used for the mass-market edition in 1973 and “for the next six years no uncensored paperback copies were in print, and no one seemed to notice”, wrote Jonathan R. Eller in the introduction to the 60th anniversary edition of the book.

Readers eventually realised and alerted Bradbury. He demanded that the publisher retract the censored version, writing that he would “not tolerate the practice of manuscript ‘mutilation’”.

- Mark Stimpson, associate editor

Too unflattering

It’s not altogether surprising that UK authorities attempted to prevent the autobiography of former MI5 officer Peter Wright, Spycatcher (co-written by Paul Greengrass), from hitting the shelves. The book did not present British intelligence agencies in a flattering light, and the government’s claims that they were suppressing its publication in the interests of security — rather than to save face — were eventually dismissed by the courts.

However, the ridiculous part about this book banning was that it only applied to England and Wales and the book was freely accessible elsewhere — including Scotland. This led to an absurd situation where newspapers around the world were reporting on the book’s contents while the press in England was subject to a gagging order, despite the information having already been revealed and books being easily shipped into the country. The ban was eventually lifted after it was acknowledged that the book wasn’t exposing any secrets due to its overseas publication.

- Daisy Ruddock, CASE coordinator

Too blasphemous

The most absurd book banning is also, arguably, the most serious in recent history. The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie was published in 1988 to deserved critical acclaim. It is a playful and complex novel that examines, among other things, the origins of Islam. The death sentence imposed on the author by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini was fuelled by, and in turn itself fuelled an ideology that believes that a novel can be blasphemous and its author should be killed. It would be laughable if the consequences weren’t so deadly.

- Martin Bright, editor at large

18 Sep 2024 | Iran, News and features, Volume 53.02 Summer 2024

In a perceptive video essay titled Irani Bag, made in 2020, Maryam Tafakory illustrates how Iranian filmmakers get around the Islamic taboo on touch. Interweaving her commentary with film clips from 1989 to 2018, she highlights how bags have long been a recurring device in Iranian films, allowing men and women to “touch” on screen.

In one clip, a man and a woman riding on a motorbike are separated – or connected – by a bag lying between them. It functions as a substitute for human touch or an object of shared intimacy.

A bag can also be an extension of the body, and Tafakory demonstrates how men and women in these scenes repeatedly push, pull or strike each other using bags.

By contrast, in the scenes she shows without a bag, hands hover centimetres away from another person – the actors forbidden from touching.

If no direct contact materialises on screen, the filmmaker can dodge censorship. And, as Tafakory shows, Iranian cinema has developed a cinematic language “to touch without touching”.

Touch is not the only prohibition in Iranian cinema. The government has sought to align cinema and other arts with its interpretation of Islamic principles, and an overarching rule is gender segregation, which prevents men and women who are not mahram (related by blood or marriage) from interacting with each other.

As part of this, the wearing of the veil in public is strictly policed, as witnessed by Mahsa Jina Amini’s police custody death in 2022 and the ensuing Woman, Life, Freedom protests. Since cinema is regarded as a public space, female characters are always expected to be veiled – even indoors with their families where they would not wear veils in real life.

Cinema is regulated by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG). Directors must submit their synopsis or screenplay for a production permit and, later, their completed film for a screening permit. At each stage they can be asked to make changes or otherwise risk censorship. When a film is released, the Iranian press can accuse the makers of siāh-namāyi: presenting the country in a negative light.

There are some obvious red lines for the censors: no direct criticism of Islam or Iran’s Islamic Republic, nothing too violent, and certainly no sex. But MCIG guidelines are not detailed, so moviemakers have learned other censorship criteria through trial and error.

What is permissible is always shifting due to changes in society and filmmakers pushing against boundaries.

It is important to observe that state censorship is not the only obstacle that Iranian filmmakers encounter. International funders and markets impose expectations of what their films should be about. Indeed, many filmmakers have reported to me that they find these restrictions to be as challenging as censorship.

But where censorship is concerned, filmmakers who want to explore intimacy and other sensitive topics must find creative ways to work around imposed constraints. This is reminiscent of Hollywood under the Production Code from 1934 to 1966 when political, religious and cultural restrictions on filmmaking compelled directors to employ subtle techniques that left more to viewers’ imaginations.

In Iranian cinema in the 1980s and 1990s, it was noticeable how often key roles were given to children. This was partly a creative response to new taboos as, in the early decades of the Islamic Republic, filmmakers realised that children could overcome constraints of gender segregation by acting as adult substitutes or purifiers of male-female contact.

For example, when the protagonist Nobar shares intimate moments with her lover Rasul in The Blue Veiled (1995), her youngest sibling, Senobar, serves as a mediator. Senobar even rests her head in Rasul’s lap, a proxy for her sister. The child lends an innocent aura to an erotically charged scene.

Children can also cross social boundaries and navigate between private and public spaces. In Jafar Panahi’s debut feature The White Balloon (1995), a little girl, Razieh, embarks on a quest to buy a goldfish for Nowruz (Persian New Year) and encounters people from different walks of life on Tehran’s streets, including an Afghan balloon seller.

Filmmakers have subtly used children to highlight Iran’s sociopolitical realities, among them the after-effects of the Iran-Iraq war (as in the 1989 film Bashu, the Little Stranger), the plight of the country’s Afghan minorities (The White Balloon) and the Kurds’ hardships on the Iran-Iraq border (for example, A Time for Drunken Horses from 2000, or 2004’s Turtles Can Fly).

The political climate has waxed and waned as moderate and hardline governments have relaxed censorship restrictions and tightened them again. Yet intermediaries for male-female contact have been enduring ploys throughout.

In one of several storylines in Tehran: City of Love (2018), a woman called Mina dates a man, Reza, who ultimately confesses he is married. As consolation, he couriers her a giant teddy bear. Subsequently, Mina is seen waiting at a bus shelter side-by-side with the gargantuan soft toy – Reza’s comic stand-in.

Another creative solution has been the use of the road movie genre. Simultaneously private and public, a car is a space that allows small, everyday transgressions. Being in a car relaxes the rules of compulsory veiling and encourages behaviour normally kept behind closed doors. It emboldens people to express themselves more freely. Filmmakers tap its emancipatory potential in both their production strategies and their on-screen representations.

In Ten (2002), a female passenger, whose fiancé has jilted her, removes her headscarf to reveal her head shaved in mourning and as a token of a new beginning. In Panahi’s Taxi Tehran (2015) – his third feature made clandestinely since his 2010 filmmaking ban – a series of passengers take a taxi. The cabbie is Panahi himself, masquerading in a beret. Before his ban, he was accustomed to filming in the bustling outdoors. With the car and small digital cameras, he can shoot outside again.

One of his passengers is lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, renowned for her work defending political prisoners. Like Panahi, she has been repeatedly imprisoned and banned from leaving Iran and practising her profession. As she gets out, she advises him to delete her words from his film to avoid more hassle from authorities. This is an underground film – made illegally, without official permits, and distributed on Iran’s black market and abroad. So Sotoudeh’s words survive the edit, registering the film’s furtive mode of production.

In Atomic Heart (2015), we first encounter Arineh and Nobahar intoxicated after a party. They are part of a modern, Westernised subculture that likes to revel, drink and take drugs, and largely rejects the Islamic Republic’s values. As their anti-regime attitude cannot be directly shown, the film hints at their unconventional lifestyle by inhabiting the road movie genre – associated with freedom and rebellion – as they whirl around nocturnal Tehran. The film evokes the subversive behaviour of real-life Iranian youth who, given restrictions on public gathering as well as bans on nightclubs and disapproval of open displays of romantic affection, have taken to the highways, especially at night.

Inserting a story within a story is a further tactic for circumventing censorship. In The Salesman (2016), Emad and Rana perform Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman in an amateur theatre group. The film mirrors the play, highlighting the couple’s relationship after Rana is assaulted by an intruder in their apartment – a scene left unshown to avoid censorship and engage the audience in speculating about what transpired between Rana and her attacker. In the story within a story, meaning is multi-layered, residing in the inner as well as the outer tale.

Since short films are less strictly regulated by screening permit requirements, directors are bypassing these rules by composing feature films from several shorts. Mohammad Rasoulof’s There Is No Evil (2020) comprises four short stories about characters involved in the state’s capital punishment system. Given Rasoulof’s filmmaking ban, his production team tactically applied for four short film permits without listing his name on the forms.

In Tales (2014), which was also created as multiple shorts joined together as a feature, a documentary filmmaker character shoots a film within a film. When an official notices his camera filming a workers’ protest, the recording halts. The film segues to the next story, suggesting the camera’s confiscation. Later, the filmmaker retrieves his camera without the seized footage. He determines to continue filming, stating: “No film will ever stay in the closet. Someday, somehow, whether we’re here or not, these films will be shown.” His words reflect a popular Iranian saying that a film’s purpose is to be shown to an audience.

These kinds of strategies are testament to Iranian filmmakers’ creativity. Although they cannot be overtly critical of the regime, they have developed resourceful ways to try to ensure that their films can explore sensitive topics and still be shown.

12 Sep 2024 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, News and features

Everything Afghan women do this week in Tirana, Albania is forbidden to them at home. Arguing. Laughing. Speaking loudly in public. Singing. Wearing brightly coloured clothes. Showing their faces. All haram according to the men from Kandahar who currently hold power. As the Taliban move to erase women across Afghanistan, in Tirana Afghan women are asking, how do we fight back?

“Until now we have been unable to sit together and listen to each other, and understand what do we want?” said Farzana Kochi. At 26, she became one of Afghanistan’s youngest MPs, representing her nomadic Kochi people. Like most of the women at the summit she was forced to flee Afghanistan when the Taliban seized power in 2021. Now aged 33, she lives in exile in Norway.

The last time I saw her, she was taking me to meet her constituents. It was May 2021, a few weeks before the withdrawal of US troops, the collapse of the government and the return of the Taliban. She was used to Taliban death threats – we travelled in a bullet-proof car, and she had been careful not to signal her movements in advance. When we arrived at the Kochi encampment, she distributed notebooks and pens to the children, but there was no school for them to attend – neither for boys nor girls. The women remained in the tents, as the men would not let them be filmed. Women’s rights, Farzana explained, had scarcely spread beyond the city limits – her work was mainly trying to alleviate poverty. In this she had the trust of the Kochi elders. “Why wouldn’t we vote for her?” one said to me. “She’s like our daughter. And she’s the only politician who comes to visit us and see our problems.”

That day, Farzana wore a brightly coloured traditional Kochi dress. After the Taliban takeover, she sent me a picture of herself in a black niqab, with only her eyes showing – the costume she wore to escape Afghanistan after the Taliban raided her office. Now, when she calls home, all her former constituents’ problems have been magnified. They are still just as poor and no politicians or NGOs are there to help them.

“It’s worse than ever,” she said. “The first thing people say is that they want to get out, to leave Afghanistan.”

According to Farzana, the priority for the women meeting in Tirana is to unite, and not let political or ethnic divisions distract them. “No matter if I’m Pashtun, I’m Kochi, I’m Uzbek, I’m Hazara, or whatever – we are targeted as women. We are all victims of the same thing.” She hopes the summit will produce a roadmap for Afghan women to present to international governments and the UN. No-one at the summit has any illusions about how long and rocky the road. For the moment, the Taliban feel secure as their opponents bicker about whether to engage or not. But until Afghan women decide how they want to resist, inside and outside the country, nothing will change.

At the end of the week, those women who came from Afghanistan will return. An older woman, who didn’t want to reveal her identity for fear of reprisals, said she would go back to give hope to younger women, to remind them that the Taliban fell from power before and will do so again – as well as to continue helping widows and orphans. Women are establishing underground schools for girls – just like the one Farzana attended back in the 1990s when she grew up under the first Taliban government.

The exiled women will scatter across the globe.

“No matter how many years go by, I will still cry,” Farzana said, fighting back the tears. “This wound is so deep and so fresh. Wherever you are, you can just live and settle. But you have all those weights on your shoulders. A country of millions of people is not something that you can give up on.”

Watch Lindsey Hilsum’s report for Channel 4 here.