Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

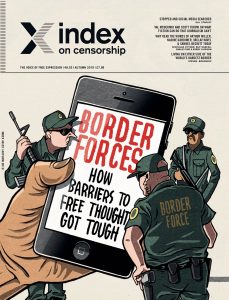

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley argues in the autumn 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine that travel restrictions and snooping into your social media at the frontier are new ways of suppressing ideas” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Border Forces – how barriers to free thought got tough

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Border officials in some countries already seek to find out about your sexual orientation via an excursion into your social media presence as part of their decision on whether to allow you in” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”How barriers to free thought got tough” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F09%2Fmagazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at borders round the world and how barriers to free thought got tough[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”108826″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/09/magazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Kerry Hudson, Chen Xiwo, Elif Shafak, Meera Selva, Steven Borowiec, Brian Patten and Dean Atta”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Border forces – how barriers to free thought got tough

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Border forces: how barriers to free thought got tough”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Big brother at the border by Rachael Jolley

Switch off, we’re landing! by Kaya Genç Be prepared that if you visit Turkey online access is restricted

Culture can “challenge” disinformation by Irene Caselli Migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean to Europe are often seen as statistics, but artists are trying to tell stories to change that

Lines of duty by Laura Silvia Battaglia It’s tough for journalists to visit Yemen, our reporter talks about how she does it

Locking the gates by Jan Fox Writers, artists, academics and musicians are self-censoring as they worry about getting visas to go to the USA

Reaching for the off switch by Meera Selva Internet shutdowns are growing as nations seek to control public access to information

Hiding your true self by Mark Frary LGBT people face particular discrimination at some international borders

They shall not pass by Stephen Woodman Journalists and activists crossing between Mexico and the USA are being systematically targeted, sometimes sent back by officials using people trafficking laws

“UK border policy damages credibility” by Charlotte Bailey Festival directors say the UK border policy is forcing artists to stop visiting

Ten tips for a safe crossing by Ela Stapley Our digital security expert gives advice on how to keep your information secure at borders

Export laws by Ryan Gallagher China is selling on surveillance technology to the rest of the world

At the world’s toughest border by Steven Borowiec South Koreans face prison for keeping in touch with their North Korean family

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson Bees and herbaceous borders

Inside the silent zone by Silvia Nortes Journalists are being stopped from reporting the disputed north African Western Sahara region

The great news wall of China by Karoline Kan China is spinning its version of the Hong Kong protests to control the news

Kenya: who is watching you? by Wana Udobang Kenyan journalist Catherine Gicheru is worried her country knows everything about her

Top ten states closing their doors to ideas by Mark Frary We look at countries which seek to stop ideas circulating[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]Small victories do count by Jodie Ginsberg The kind of individual support Index gives people living under oppressive regimes is a vital step towards wider change[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Germany’s surveillance fears by Cathrin Schaer Thirty years on from the fall of the Berlin wall and the disbanding of the Stasi, Germans worry about who is watching them

Freestyle portraits by Rachael Jolley Cartoonists Kanika Mishra from India, Pedro X Molina from Nicaragua and China’s Badiucao put threats to free expression into pictures

Tackling news stories that journalists aren’t writing by Alison Flood Crime writers Scott Turow, Val McDermid, Massimo Carlotto and Ahmet Altan talk about how the inspiration for their fiction comes from real life stories

Mosul’s new chapter by Omar Mohammed What do students think about the new books arriving at Mosul library, after Isis destroyed the previous building and collection?

The [REDACTED] crossword by Herbashe The first ever Index crossword based on a theme central to the magazine

Cries from the last century and lessons for today by Sally Gimson Nadine Gordimer, Václav Havel, Samuel Beckett and Arthur Miller all wrote for Index. We asked modern day writers Elif Shafak, Kerry Hudson and Emilie Pine plus theatre director Nicholas Hytner why the writing is still relevant

In memory of Andrew Graham-Yooll by Rachael Jolley Remembering the former Index editor who risked his life to report from Argentina during the worst years of the dictatorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Backed into a corner by love by Chen Xiwo A newly translated story by censored Chinese writer about the abusive relationship between a mother and daughter plus an interview with the author

On the road by Marguerite Duras The first English translation of an extract from the screenplay of the 1977 film Le Camion by one of the greatest French writers of the 20th century

Muting young voices by Brian Patten Two poems, one written exclusively for Index, about how the exam culture in schools can destroy creativity by the Liverpool Poet

Finding poetry in trauma by Dean Atta Male rape is still a taboo subject, but very little is off-limits for this award-winning writer from London who has written an exclusive poem for Index[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]Index around the world: Tales of the unexpected by Sally Gimson and Lewis Jennings Index has started a new media monitoring project and has been telling folk stories at this summer’s festivals[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Endnote: Macho politics drive academic closures by Sally Gimson Academics who teach gender studies are losing their jobs and their funding as populist leaders attack “gender ideology”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship expresses concern over a decision to bar reporters from the Defence and Security Equipment International (DSEI) trade fair at Excel London beginning 10 September.

“We are very concerned at the decision to refuse Ian Cobain and Solomon Hughes accreditation to next week’s DSEI arms fair. It is difficult to understand how and why the DSEI’s security team could have come to this decision and it raises serious questions about whether it was politically motivated, particularly given that it came hours after a UN report warned that the UK may have been complicit in Saudi war crimes in Yemen.

As a UK government-backed event, the DSEI’s decision undermines the government’s commitment to media freedom. Press freedom is essential to hold power to account and on the basis that we consider this a violation, we have filed an alert with the Council of Europe,” said Jessica Ní Mhainín, policy research and advocacy officer, Index on Censorship.

[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1567782857918-993a84c6-1493-2″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index calls on the UK to stand up to the Bahrain government on human rights after police storm the London embassy to protect protester” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Human rights activist Nabeel Rajab who is still in prison in Bahrain for criticising the government

Human rights defender Moosa Mohammed climbed on to the roof of the Bahraini embassy in London on July 26 to protest the execution of two men in Bahrain who had been tortured in prison and given the death penalty. His banner read: “I am risking my life to save two men about to be executed in the next few hours. Boris Johnson act now!”

He intended to stay on the roof until the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson contacted the King of Bahrain to stop the executions that were due to take place on the morning of 28 July. However, as a Channel 4 News video shows, at least two people appeared on the roof and someone started beating him with a stick, and according to the protester, they threatened to kill him and throw him down the stairwell. Since the embassy is a private building, video reports appear to confirm that these two men must be embassy staff.

Diplomatic premises in the UK may not be entered by the UK police unless ordered under the consent of the ambassador or head of mission, even though they are considered part of UK territory as outlined in the Diplomatic Privileges Act. The embassy has said the claims were “unfounded” and said it was reacting to a perceived terrorism threat. But what happened on the night of the protest was clearly extremely serious as it caused UK police officers to take a highly unusual step and break down the door of the embassy to force entry to the building.

A spokesperson for the Metropolitan Police told The Independent newspaper that police were called following reports of a man on the roof. According to the spokesperson, officers and London Fire Brigade attended and “hearing a disturbance on the roof, officers entered the building and detained the man”. But a police officer confirms on the video that they were “forcing entry”.

If Bahrain’s embassy staff members feel confident enough to act like this on UK territory, what is happening inside Bahrain as the rest of the world chooses not to watch?

Freedom of expression in Bahrain continues to be under severe threat. Joy Hyvarinen, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship said: “The people most at risk are those who choose to freely express themselves, whether they be journalists, activists or photographers, but ordinary citizens can face repercussions if they follow, retweet, comment or like a Twitter or Facebook post”.

The Bahraini government has used its 2002 Press Law to restrict the rights of the media to the point where a journalist can face up to five years’ imprisonment for publishing criticism of Islam or the King, inciting actions that undermine state security, or advocating a change in government. The government also uses counterterrorism legislation to limit freedom of expression.

One of the most prominent activists and defenders of freedom of expression in Bahrain is Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award winner Nabeel Rajab, who was convicted under these laws and has been detained since June 2016. He was first charged and given a two-year prison sentence for TV interviews he gave in 2015 and 2016, on the grounds of “disseminating false news, statements and rumours about the internal situation of the kingdom that would undermine its prestige and status”. He was later sentenced to an additional five years on charges of “spreading false rumours in time of war,” “insulting public authorities,” and “insulting a foreign country” for tweets that were critical of torture in Bahraini prisons and the war in Yemen.

Rajab’s case is only one of many human rights violations taking place in Bahrain, where people are unjustly convicted and arbitrarily detained. Many prisoners are subjected to ill-treatment and torture is not uncommon. Earlier this month, groups called on Amal Clooney, the United Kingdom’s Special Envoy on Media Freedom, urging her to pressure the UK to act on Bahrain’s suppression of freedom of expression. After the incident at the Bahrain embassy in London, will the UK government finally take a tougher approach to Bahrain or will it continue to make deals with a government with so little regard for human rights?

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1566216380084-99e48680-305a-4″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]