Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

After being jailed for her art, Kurdish journalist Zehra Doğan’s paint supplies were confiscated. She was charged with peddling terrorist propaganda when she drew a scene of a destroyed Kurdish-majority city in southern Turkey. In prison, she asked fellow inmates to give her their menstrual blood to use as paint. Meanwhile, she had the support of activists around the world. Graffiti artist Banksy painted a mural in New York calling for her release. Listen to the podcast here.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”我们绝食!我们抗议!我们呼吁!我们忏悔!”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”106533″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

我们不是寻找死亡。我们寻找真的生命。

在李鹏政府非理性的军事暴力高压之下,中国知识界必须结束几千年遗传下来的只动口而不动手的软骨症,以行动抗议军管:以行动呼吁一种新的政治文化的诞生;以行动忏悔由于我们长期的软弱所犯下的过失。对于中华民族的落伍,我们人人都负有一份责任。

对于中华民族的落伍,我们人人都负有一份责任。

绝食的目的

此次在中国历史上空前的民主运动,一直採取合法的、非暴力的、理性的和平方式来争取自由、民主和人权,但是,李鹏政府居然以几十万军队来压制手无寸铁的大学生和各界民众。为此,我们绝食,不再是为了请愿,而是为了抗议戒严和军管!我们主张以和平的方式推进中国的民主化进程,反对任何形式的暴力。但是,我们不畏强暴,我们要以和平的方式来显示民间的民主力量的坚韧,以粉碎靠刺刀和谎言来维繫的不民主的秩序!这种对和平请愿的学生和各界民众实行戒严和军管的极端荒谬悖理的蠢举在中华人民共和国的历史上开了一个极为恶劣的先例,使共产党、政府和军队蒙受了巨大的耻辱,将十年改革、开放的成果毁于一旦!

中国几千年的历史,充满了以暴易暴和相互仇恨。及至近代,敌人意识成为中国人的遗传;一九四九年以后的「以阶级斗争为纲」的口号,更把传统的仇恨心理、敌人意识和以暴易暴推向了极端。

此次军管也是「阶级斗争」式的政治文化的体现。为此,我们绝食,呼吁中国人从现在开始逐渐废弃和消除敌人意识和仇恨心理,彻底放弃「阶级斗争」式的政治文化。

因为仇恨只能产生暴力和专制。我们必须以一种民主式的。宽容精神和协作意识来开始中国的民主建设。民主政治是没有敌人和仇恨的政治,只有在相互尊重、相互宽容、相互妥协基础上的协商、讨论和表决。

李鹏作为总理犯有重大失误,应该按照民主程序引咎辞职。但是,李鹏不是我们的敌人,即使他下台,仍然具有一个公民应享有的权利,甚至可以拥有坚持错误主张的权利。我们呼吁,从政府到每一位普通公民,放弃旧的政治文化,开始新政治文化。我们要求政府立即结束军管,并呼吁学生和政府双方重新以和平谈判、协商对话的方式来解决双方的对立。

此次学生运动,获得了空前的全社会各阶层的同情、理解和支持,军管的实施,已把这次学生运动转变为全民的民主运动。但无法否认的是,有很多人对学生的支持是出于人道主义的同情心和对政府的不满,而缺乏一种具有政治责任感的公民意识。为此,我们呼吁,全社会应该逐步地放弃旁观者和单纯的同情态度,建立公民意识。公民意识首先是政治权利平等的意识,每个公民都应该有自信:自己的政治权利与总理是平等的。

其次,公民意识不只是正义感和同情心,更是理性化的参与意识,也就是政治责任感。每个人不只是同情与支持,而且要直接参与民主建设。最后,公民意识是承担责任和义务的自觉性。社会政治合理合法,有每个人的功劳:而社会政治不合理不合法。也有每个人的责任。自觉地参与社会政治和自觉地承担责任,是每个公民的天职。中国人必须明确:在民主化的政治中,每个人首先是公民,其次才是学生、教授、工人、干部、军人等。

几千年来,中国社会是在打倒一个旧皇帝而树立一个新皇帝的恶性循环中度过的。历史证明:某位失去民心的领导人的下台和某位深得民心的领导人的上台并不能解决中国政治的实质性问题。我们需要的不是完美的救世主而是完善的民主制度。

为此,我的呼吁:第一,全社会应该通过各种方式建立起合法的民间自治组织,逐渐形成民间的政治力量对政府决策的制衡。因为民主的精髓是制衡。我们宁要十个相互制衡的魔鬼,也不要一个拥有绝对权力的天使。第二,通过罢免犯有严重失误的领导人,逐步建立起一套完善的罢免制度。谁上台和谁下台并不重要,重要的是怎样上台和怎样下台。非民主程序的任免只能导致独裁。

在此次运动中,政府和学生都有失误。政府的失误主要是在旧的「阶级斗争」式政治思维的支配下,站在广大学生和市民的对立面,致使冲突不断加剧;

学生的失误主要是自身组织的建设太不完善,在争取民主的过程中,出现了大量非民主的因素。因此,我们呼吁,政府和学生双方都要进行冷静的自我反省。我们认为,就整体而言,此次运动中的错误主要在政府方面。游行、绝食等行动是人民表达自己意愿的民主方式,是完全合法合理的,根本就不是动乱。

而政府方面无视宪法赋予每个公民的基本权利,以一种专制政治的思维把此次运动定名为动乱,从而又引出了一连串的错误决策,致使运动一次次升级,对抗愈演愈烈。因而,真正制造动乱的是政府的错误决策,其严重程度不下于“文革”。只是由于学生和市民的克制,社会各界包括党、政、军有识之士的强烈呼吁,才没有出现大规模的流血事件。鉴于此,政府必须承认和反省这些错误,我们认为现在改正还不算太晚。

政府应当从这次大规模的民主运动当中汲取沉痛的教训,学会习惯于倾听人民的声音,习惯于人民用宪法赋予的权利来表达自己的意愿,学会民主地治理国家。全民的民主运动正在教会政府怎样地以民主和法制来治理社会。学生方面的失误主要表现在内部组织的溷乱、缺乏效率和民主程序。诸如,目标是民主的而手段、过程是非民主的;理论是民主的而处理具体问题是非民主的;缺乏合作精神,权力相互抵销,造成决策的零乱状态;财务上的溷乱,物质上的浪费;情感有馀而理性不足;特权意识有馀而平等意识不足;等等。近百年来,中国人民争取民主的斗争,大都停留在意识形态化和口号化的水平上。只讲思想启蒙,不讲实际操作;只讲目标,而不讲手段、过程、程序。我们认为:民主政治的真正实现,是操作的过程、手段和程序的民主化。为此,我们呼吁,中国人应该放弃传统的单纯意识形态化、口号化、目标化的空洞民主,而开始操作的过程、手段和程序的民主建设,把以思想启蒙为中心的民主运动转化为实际操作的民主运动,从每一件具体的事情做起。我们呼吁:学生方面要以整顿天安门广场的学生队伍为中心进行自我反省。

政府在决策方面的重大失误还表现在所谓的「一小撮」的提法上。通过绝食,我们要告诉国内外舆论界,所谓的「一小撮」是这样一类人:他们不是学生,但是他们作为有政治责任感的公民主动地参与了这次以学生为主体的全民民主运动。我们所做的一切都是合理合法的,他们想用自己的智慧和行动让政府从政治文化、人格修养、道义力量等方面知所愧悔,公开承认并改正错误,并使学生的自治组织按照民主和法制程序日益完善。

必须承认,民主地治理国家,对每个中国公民来说都是陌生的,全体中国公民都必须从头学起。包括党和国家的最高领导人。在这个过程中,政府和民众两方面的失误都是不可避免的。关键在于知错必认、知错必改,从错误中学习,把错误转化为积极的财富,在不断地改正错误中逐步地学会民主地治理我们的国家。

二、我们的基本口号

1.我们没有敌人!不要让仇恨和暴力毒化了我们的智慧和中国的民主化进程!

2.我们都需要反省!中国的落伍人人有责!

3.我们首先是公民!

4.我们不是寻找死亡!我们寻找真的生命!

三、绝食的地点、时间、规则

刘晓波 周舵 侯德健 高新

[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1556703802152-2a735b4e-99ef-10″ taxonomies=”29029″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine produces regular podcasts in which we speak to some of the most interesting writers, thinkers and activists around the globe.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine produces regular podcasts in which we speak to some of the most interesting writers, thinkers and activists around the globe.

Click here to see what’s in our archive.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, Index on Censorship magazine explores the free speech issues from around the world today.

Explore recent issues here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Responding to violations of media freedom in Hungary has become a conundrum for the EU. With populist parties poised for large gains in the next European election, Sally Gimson explores in the spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine what the EU could do to uphold free speech in member countries” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán. Credit: EU2017EE Estonian Presidency / Flickr

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”It’s like joining a sorority with very strict rules for entering, but when you are there you can misbehave and it is covered up by the group” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”I think Europeans generally made the mistake of thinking that it doesn’t matter if we have one small country which is going the wrong way” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

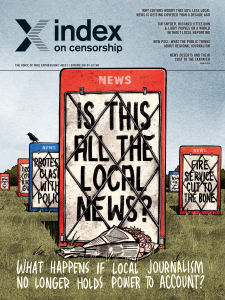

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the local news?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine asks Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?

With: Libby Purves, Julie Posetti and Mark Frary[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article has been updated on 18 April 2019 to reflect that the name of organisation Lutz Kinkel works for had been written incorrectly. The article read “European Centre for Press and Media Reform”, when it should have read “European Centre for Press and Media Freedom”.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article has been updated on 18 April 2019 to reflect that the name of organisation Lutz Kinkel works for had been written incorrectly. The article read “European Centre for Press and Media Reform”, when it should have read “European Centre for Press and Media Freedom”.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”97% of editors of local news worry that the powerful are no longer being held to account ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Ninety seven per cent of senior journalists and editors working for the UK’s regional newspapers and news sites say they worry that that local newspapers do not have the resources to hold power to account in the way that they did in the past, according to a survey carried out by the Society of Editors and Index on Censorship. And 70% of those respondents surveyed for a special report published in Index on Censorship magazine are worried a lot about this.

The survey, carried out in February 2019 for the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, asked for responses from senior journalists and current and former editors working in regional journalism. It was part of work carried out for this magazine to discover the biggest challenges ahead for local journalists and the concerns about declining local journalism has on holding the powerful to account.

The survey found that 50% of editors and journalists are most worried that no one will be doing the difficult stories in future, and 43% that the public’s right to know will disappear. A small number worry most that there will be too much emphasis on light, funny stories.

There are some specific issues that editors worry about, such as covering court cases and council meetings with limited resources.

Twenty editors surveyed say that they feel only half as much local news is getting covered in their area compared with a decade ago, with 15 respondents saying that about 10% less news is getting covered. And 74% say their news outlet covers court cases once a week, and 18% say they hardly ever cover courts.

The special report also includes a YouGov poll commissioned for Index on public attitudes to local journalism. Forty per cent of British adults over the age of 65 think that the public know less about what is happening in areas where local newspapers have closed, according to the poll.

Meanwhile, 26% of over-65s say that local politicians have too much power where local newspapers have closed, compared with only 16% of 18 to 24-year-olds. This is according to YouGov data drawn from a representative sample of 1,840 British adults polled on 21-22 February 2019.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]The Index magazine special report charts the reduction in local news reporting around the world, looking at China, Argentina, Spain, the USA, the UK among other countries.

Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley said: “Big ideas are needed. Democracy loses if local news disappears. Sadly, those long-held checks and balances are fracturing, and there are few replacements on the horizon. Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be.”

She added: “If no local reporters are left living and working in these communities, are they really going to care about those places? News will go unreported; stories will not be told; people will not know what has happened in their towns and communities.”

Others interviewed for the magazine on local news included:

Michael Sassi, editor of the Nottingham Post and the Nottingham Live website, who said: “There’s no doubt that local decision-makers aren’t subject to the level of scrutiny they once were.”

Lord Judge, former lord chief justice for England and Wales, said: “As the number of newspapers declines and fewer journalists attend court, particularly in courts outside London and the major cities, and except in high profile cases, the necessary public scrutiny of the judicial process will be steadily eroded,eventually to virtual extinction.”

US historian and author Tim Snyder said: “The policy thing is that government – whether it is the EU or the United States or individual states – has to create the conditions where local media can flourish.”

“A less informed society where news is replaced by public relations, reactive commentary and agenda management by corporations and governments will become dangerously volatile and open to manipulation by special interests. Allan Prosser, editor of the Irish Examiner.

“The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial. Belgian journalist Jean Paul Marthoz.

The special report “Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?” is part of the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Note to editors: Index on Censorship is a quarterly magazine, which was first published in 1972. It has correspondents all over the world and covers freedom of expression issues and censored writing

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the Local News?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores what happens to democracy without local journalism, and how it can survive in the future.

With: Richard Littlejohn, Libby Purves and Tim Snyder[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]