27 May 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, European Union, Press Releases

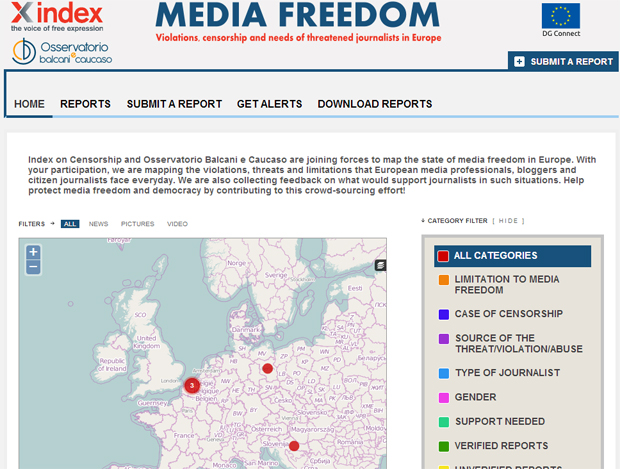

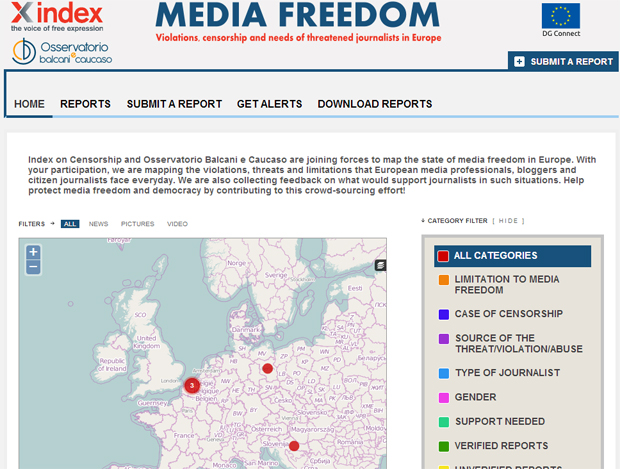

Index on Censorship and Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso are launching mediafreedom.ushahidi.com to track media violations in Europe.

Index on Censorship, (London, United Kingdom) and Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, (Rovereto, Italy) have launched mediafreedom.ushahidi.com, a website that will enable the reporting and mapping of media freedom violations across the 28 EU countries plus candidate countries. The platform will collect and map out crowd-sourced information from media professionals and citizen journalists across Europe over the course of a year.

Based in London, Index on Censorship is an international organisation that promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression. Since its founding in 1972, Index has used a unique combination of journalism, campaigning and advocacy to defend freedom of expression for those facing censorship and repression, including journalists, writers, social media users, bloggers, artists, politicians, scientists, academics, activists and citizens.

“Index believes that free expression is the foundation of a free society and this website will enable journalists to report incidences of violations as soon as they happen. By mapping these reports online, the entire system will act as an advocacy, research and response tool, highlighting that violations on media freedom still occur in Europe.” explained Melody Patry, Index on Censorship senior advocacy officer.

Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso (OBC) has been reporting on the socio-political and cultural developments of South-East Europe since 2000. Through the online platform, OBC will monitor and document media freedom violations in 11 countries, among which Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Romania, Serbia and others, and collect the needs of journalists under threat.

“We aim at improving the working conditions of media professionals and citizen journalists in Italy, South-East Europe and Turkey and ultimately at enhancing the quality of European democracy,” said Luisa Chiodi, scientific director of OBC.

This new website is part of a European Commission grant project under the EU’s Digital Agenda (DG Connect). In light of remaining violations to media freedom and plurality in Europe, and longer-term challenges in the digital age, the DG Connect launched a call for proposals to address the issue.

The successful candidates- the International Press Institute, Index on Censorship, Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso together with SEEMO, Ossigeno per l’Informazione and Dr Siapera, as well as the European University Institute in cooperation with the Central European University– will spend the next year working on four projects, under the title European Centre for Press and Media Freedom.

For more information on the projects and the website, please read EU project to explore media freedom and pluralism or contact Melody Patry, [email protected], +44 (0) 207 260 2671 or OBC, [email protected].

27 May 2014 | About Index, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

(Photo: Anatolii Stepanov / Demotix)

Free speech has always been a concern to the EU, with flaws in the world of press freedom and pluralism in Europe still apparent today. In an attempt to raise awareness to these problems, both on an institutional scale and publicly, DG Connect, tasked with undertaking the EU’s Digital Agenda, launched a call for proposal for funding for a new project to allow NGOs and civil society platforms to research and develop tools to tackle this problem.

The successful candidates- the International Press Institute, Index on Censorship, Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and the European University Institute in cooperation with the Central European University– will spend the next year working on the project, under the title European Centre for Press and Media Freedom.

“It is true that we regularly receive concerns about media freedom and pluralism that come from citizens, NGOs and the European Parliament,” Lorena Boix Alonso, Head of Unit for converging media and content at DG Connect told Index.

The Vice President of the European Commission, Neelie Kroes, began implementing action on this topic in 2011 with the creation of a high level group on media freedom and pluralism, but there are still violations in the world of European media freedom that need to be dealt with. These projects will be useful to raise awareness, according to Boix Alonso, to something which many people have little knowledge on.

Index on Censorship

In 2013, an Index on Censorship report showed that, despite all EU member states’ commitment to free expression, the way these common values were put into practice varied from country to country, with violations regularly occurring.

Building on this report, the DG Connect-funded project will enable Index to implement real-time mapping of violations to media freedom on a website that covers 28 EU countries and five candidate countries. Working with regional correspondents, specialist digital tools will be used to capture reports via web and mobile applications, for which workshop training will be provided. Index led events across Europe will discuss the contemporary challenges currently facing media professionals, allowing them to share good practices, while learning how to use the tools.

“Index believes that free expression is the foundation of a free society. Enabling journalists to report on matters without the threat of censorship or violations against them means promoting the right to freedom of expression and information, which is a fundamental and necessary condition for the promotion and protection of all human rights in a democratic society,” explained Melody Patry, Index on Censorship Senior Advocacy Officer.

The DG Connect grant demonstrates the current focus of the EU on the needs of journalists and citizens who face these violations to media freedom and plurality, according to Patry, as well as longer term challenges in the digital age.

Click here to visit the mediafreedom.ushahidi.com website

The Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom

For some, the need to safeguard media freedom is at the forefront of the work they do. The Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) is one such organisation and, in collaboration with the Centre for Media and Communication Studies (CMCS) at the Central European University, will continue to do so with funding from DG Connect for their project Strengthening Journalism in Europe: Tools, Networking, Training.

“The role of journalists is to both serve as guardians of government power and to enable the public to make informed decisions about key social and political issues that affect their daily lives,” the CMPF and CMCS told Index.

“The ability of journalists to freely report on issues without censorship is therefore critical- it’s the cornerstone of the checks and balances that make democracies work.”

The collaborative project will develop legal support, resources and tools for reporters, editors and media outlets to help them defend themselves in cases of legal threat, as well as raising awareness to ongoing violations to free expression and how these “impact the foundation on which democratic systems are based.” NGOs and policy makers will also benefit from this EU-funded scheme.

The International Press Institute

For over 60 years the International Press Institute (IPI) has been defending press freedom around the world, working to improve press legislation, influencing the release of imprisoned journalists and ensuring the media can carry out its work without restrictions.

London may have earned the title over recent years of libel capital of the world but what restrictions are placed on European journalists through defamation laws? This question forms the base of the IPI project, analysing existing laws and practices relating to defamation on both a civil and criminal nature; comparing this to international and European standards; and looking to the extent of which these affect the profession of journalism in all 28 EU countries and five candidate states.

After initial research, workshops will be hosted in four countries where the IPI believes they will have the greatest impact on the ground in countries where press freedom is limited by defamation to teach journalists which defamation laws affect their work, what the legitimate limits to press freedom are and what goes beyond what is internationally accepted.

According to the IPI the EU currently has no strong standards with regards to defamation and the threat to press freedom, a fact the led to their project proposal. “We hope that at one point the work we are doing will lead to a discussion within the EU about the need to develop these standards,” Barbara Trionfi, IPI Press Freedom Manager, explained to Index. “The defence of press freedom is a fight anywhere and it does not stop even in western Europe. It is still a major problem.”

Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso

“We aim at improving the working conditions of media professionals and citizen journalists in Italy, South-East Europe and Turkey and ultimately at enhancing the quality of democracy,” Francesca Vanoni, Project Manager at Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso (OBC) told Index.

OBC has been reporting on the socio-political and cultural developments of south-east Europe since 2000 and through their DG Connect funded project will monitor and document media freedom violations in nine countries, including Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Romania and Serbia.

Offering practical support to threatened journalists, the project will raise public awareness of the European dimension on media freedom and pluralism, stimulating an active role of the EU with regard to media pluralism in both member states and candidate countries. This will be implemented, among other means, through social media campaigns, a crowd-sourcing platform, an international conference for the exchange of best practices and transnational public debates.

The idea behind the project was to help build a European transnational public sphere in order to strengthen the EU itself. The ethics and professionalism of media workers is crucial, according to Vanoni. A democratic environment is built upon the contribution of all parts involved: “The protection of media freedom is fundamental for the European democracy and it cannot be left aside of the main political priorities.

“Being part of a wider political community that tackles shared problems with shared solutions offers stronger protection in case pluralism is threatened,” explained Vanoni.

To make a report, please visit http://mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

This article was published on May 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Apr 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases

VIENNA, April 30, 2014 – The European Commission’s support for projects addressing violations of media freedom and pluralism, and providing practical support to journalists, gives European Union countries reason to celebrate this year on May 3, World Press Freedom Day, media freedom watchdogs said today.

However, new research into defamation law and practice – one of four, one-year projects launched in February under a Commission-funded grant programme focusing on the 28 EU member and five candidate countries – has shed light on one big elephant in the room, the Vienna-based International Press Institute (IPI) said. Preliminary results of a study by IPI and the Center for Media and Communications Studies (CMCS) at Budapest’s Central European University reveal that criminal laws in the EU addressing libel, slander, and insult remain rife and, in many cases, contravene international and European standards.

Furthermore, as another project, “Safety Net for European Journalists”, registered, attacks on journalists continue to represent a major challenge to press freedom in Europe. Research and field work by the Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, IPI affiliate the South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO), Ossigeno per l’Informazione and Dr. Eugenia Siapera of Dublin City University have shown that journalists across Southeast Europe, Turkey and Italy often face common threats and pressure, highlighting a crucial need for transnational support.

“Media freedom and pluralism can unfortunately not be taken for granted in Europe,” Neelie Kroes, vice-president of the European Commission responsible for the Digital Agenda, said. “We all, governments, NGOs, the media, and the EU institutions have a role to play in standing firmly to defend these principles, in Europe and beyond, now and tomorrow, on and off-line. I am interested to see what the outcome of the independent projects will be.”

The European Commission grant programme, the “European Centre for Press and Media Freedom”, is funding two projects in addition to IPI’s project researching the effects of defamation laws on journalism in Europe and raising awareness of the same, and the “Safety Net” project establishing a transnational support network for journalists in Southeast Europe, Turkey and Italy. Index on Censorship has created a project to map media freedom violations, and the Florence-based Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), also working in conjunction with CMCS, is creating tools and networks to strengthen journalism in Europe.

The grantees’ work, combating violations of the fundamental right to press and media freedom, is intended to play a critical role in protecting both the fundamental human right of free expression, as guaranteed by Article 11 of the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, as well as the media’s instrumental role in safeguarding democratic order.

Some of the grantees will also collaborate to establish an intra-European network of legal assistance for media outlets facing legal proceedings.

IPI and CMCS plan to launch a comprehensive report in early June on the status of criminal and civil defamation law in EU member and candidate countries, intended to help identify states where engagement is required most urgently. The report will evaluate each country across a number of categories, including the types of defences and punishments available and the existence of provisions shielding public officials, heads of state, or national symbols from criticism. It will also include a first-of-its-kind “perception index” to gauge the subjective effect that criminal and civil defamation proceedings have on press freedom.

Preliminary research shows that, in nearly all EU member states, libel and insult remain criminal offences punishable with imprisonment – up to five years in some cases – and that journalists continue to face prosecutions in numerous countries, particularly Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta and Portugal. While some countries have seen movement toward decriminalisation, only a small minority of states have fully abolished criminal libel and insult provisions, among them Ireland, Romania and Britain.

A key finding so far is that while national courts in many cases apply European Court of Human Rights precedents on protection of freedom of expression, few EU member states have adopted legislation that meets these standards. This is particularly true with regard to defences available to journalists in libel proceedings. In IPI’s view, the lack of modern legislation clearly establishing defences of truth, public interest, fair comment and honest opinion contributes to an atmosphere of uncertainty and potential self-censorship on matters of public interest.

Additionally, the research so far has shown that legal protections shielding public officials from scrutiny are prevalent in many countries, and that such provisions often are found in tandem with increased punishments for journalists and media outlets that publish content that could be deemed defamatory. The combination of these two instruments – present in the laws of many EU member states – significantly weakens legal safeguards that enable journalists and media outlets to perform their necessary watchdog roles. Such barriers pose undue restrictions on freedom of expression rights and the public’s right to know, as established by international and EU conventions and treaties.

Despite clear challenges, however, the research has also found several important positive movements, including the enactment of modern civil defamation legislation in Ireland in 2009 and in England and Wales in 2013, as well as the full repeal of criminal libel in those jurisdictions. The removal, for the most part, of prison sentences as a punishment for libel in Finland, new discussions among Italian lawmakers to end imprisonment for criminal defamation and the repeal of a French law punishing insults to the president all indicate a growing, if slow, willingness to tackle archaic legislation.

If you would like more information or to schedule an interview with IPI Senior Press Freedom Adviser Steven M. Ellis, please call +43 (1) 512 9011 or email [email protected].

15 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Index Reports, News and features, Politics and Society

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Beyond its near neighbourhood, the EU works to promote freedom of expression in the wider world. To promote freedom of expression and other human rights, the EU has 30 ongoing human rights dialogues with supranational bodies, but also large economic powers such as China.

The EU and freedom of expression in China

The focus of the EU’s relationship with China has been primarily on economic development and trade cooperation. Within China some commentators believe that the tough public noises made by the institutions of the EU to the Chinese government raising concerns over human rights violations are a cynical ploy so that EU nations can continue to put financial interests first as they invest and develop trade with the country. It is certainly the case that the member states place different levels of importance on human rights in their bilateral relationships with China than they do in their relations with Italy, Portugal, Romania and Latvia. With China, member states are often slow to push the importance of human rights in their dialogue with the country. The institutions of the European Union, on the other hand, have formalised a human rights dialogue with China, albeit with little in the way of tangible results.

The EU has a Strategic Partnership with China. This partnership includes a political dialogue on human rights and freedom of the media on a reciprocal basis.[1] It is difficult to see how effective this dialogue is and whether in its present form it should continue. The EU-China human rights dialogue, now 14 years old, has delivered no tangible results.The EU-China Country Strategic Paper (CSP) 2007-2013 on the European Commission’s strategy, budget and priorities for spending aid in China only refers broadly to “human rights”. Neither human rights nor access to freedom of expression are EU priorities in the latest Multiannual Indicative Programme and no money is allocated to programmes to promote freedom of expression in China. The CSP also contains concerning statements such as the following:

“Despite these restrictions [to human rights], most people in China now enjoy greater freedom than at any other time in the past century, and their opportunities in society have increased in many ways.”[2]

Even though the dialogues have not been effective, the institutions of the EU have become more vocal on human rights violations in China in recent years. For instance, it included human rights defenders, including Ai Weiwei, at the EU Nobel Prize event in Beijing. The Chinese foreign ministry responded by throwing an early New Year’s banquet the same evening to reduce the number of attendees to the EU event. When Ai Weiwei was arrested in 2011, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton issued a statement in which she expressed her concerns at the deterioration of the human rights situation in China and called for the unconditional release of all political prisoners detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression.[3] The European Parliament has also recently been vocal in supporting human rights in China. In December 2012, it adopted a resolution in which MEPs denounced the repression of “the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, press freedom and the right to join a trade union” in China. They criticised new laws that facilitate “the control and censorship of the internet by Chinese authorities”, concluding that “there is therefore no longer any real limit on censorship or persecution”. Broadly, within human rights groups there are concerns that the situation regarding human rights in China is less on the agenda at international bodies such as the Human Rights Council[4] than it should be for a country with nearly 20% of the world’s population, feeding a perception that China seems “untouchable”. In a report on China and the International Human Rights System, Chatham House quotes a senior European diplomat in Geneva, who argues “no one would dare” table a resolution on China at the HRC with another diplomat, adding the Chinese government has “managed to dissuade states from action – now people don’t even raise it”. A small number of diplomats have expressed the view that more should be done to increase the focus on China in the Council, especially given the perceived ineffectiveness of the bilateral human rights dialogues. While EU member states have shied away from direct condemnation of China, they have raised freedom of expression abuses during HRC General Debates.

The Common Foreign and Security Policy and human rights dialogues

The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is the agreed foreign policy of the European Union. The Maastricht Treaty of 1993 allowed the EU to develop this policy, which is mandated through Article 21 of the Treaty of the European Union to protect the security of the EU, promote peace, international security and co-operation and to consolidate democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights and fundamental freedom. Unlike most EU policies, the CFSP is subject to unanimous consensus, with majority voting only applying to the implementation of policies already agreed by all member states. As member states still value their own independent foreign policies, the CFSP remains relatively weak, and so a policy that effectively and unanimously protects and promotes rights is at best still a work in progress. The policies that are agreed as part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy therefore be useful in protecting and defending human rights if implemented with support. There are two key parts of the CFSP strategy to promote freedom of expression, the External Action Service guidelines on freedom of expression and the human rights dialogues. The latter has been of variable effectiveness, and so civil society has higher hopes for the effectiveness of the former.

The External Action Service freedom of expression guidelines

As part of its 2012 Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy, the EU is working on new guidelines for online and offline freedom of expression, due by the end of 2013. These guidelines could provide the basis for more active external policies and perhaps encourage a more strategic approach to the promotion of human rights in light of the criticism made of the human rights dialogues.

The guidelines will be of particular use when the EU makes human rights impact assessments of third countries and in determining conditionality on trade and aid with non-EU states. A draft of the guidelines has been published, but as these guidelines will be a Common Foreign and Security Policy document, there will be no full and open consultation for civil society to comment on the draft. This is unfortunate and somewhat ironic given the guidelines’ focus on free expression. The Council should open this process to wider debate and discussion.

The draft guidelines place too much emphasis on the rights of the media and not enough emphasis on the role of ordinary citizens and their ability to exercise the right to free speech. It is important the guidelines deal with a number of pressing international threats to freedom of expression, including state surveillance, the impact of criminal defamation, restrictions on the registration of associations and public protest and impunity against human right defenders. Although externally facing, the freedom of expression guidelines may also be useful in indirectly establishing benchmarks for internal EU policies. It would clearly undermine the impact of the guidelines on third parties if the domestic policies of EU member states contradict the EU’s external guidelines.

Human rights dialogues

Another one of the key processes for the EU to raise concerns over states’ infringement of the right to freedom of expression as part of the CFSP are the human rights dialogues. The guidelines on the dialogues make explicit reference to the promotion of freedom of expression. The EU runs 30 human rights dialogues across the globe, with the key dialogues taking place in China (as above), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Georgia and Belarus. It also has a dialogues with the African Union, all enlargement candidate countries (Croatia, the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia and Turkey), as well as consultations with Canada, Japan, New Zealand, the United States and Russia. The dialogue with Iran was suspended in 2006. Beyond this, there are also “local dialogues” at a lower level, with the Heads of EU missions, with Cambodia, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Israel, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, the Palestinian Authority, Sri Lanka, Tunisia and Vietnam. In November 2008, the Council decided to initiate and enhance the EU human rights dialogues with a number of Latin American countries.

It is argued that because too many of the dialogues are held behind closed doors, with little civil society participation with only low-level EU officials, it has allowed the dialogues to lose their importance as a tool. Others contend that the dialogues allow the leaders of EU member states and Commissioners to silo human rights solely into the dialogues, giving them the opportunity to engage with authoritarian regimes on trade without raising specific human rights objections.

While in China and Central Asia the EU’s human rights dialogues have had little impact, elsewhere the dialogues are more welcome. The EU and Brazil established a Strategic Partnership in 2007. Within this framework, a Joint Action Plan (JAP) covering the period 2012-2014 was endorsed by the EU and Brazil, in which they both committed to “promoting human rights and democracy and upholding international justice”. To this end, Brazil and the EU hold regular human rights consultations that assess the main challenges concerning respect for human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law; advance human rights and democracy policy priorities and identify and coordinate policy positions on relevant issues in international fora. While at present, freedom of expression has not been prioritised as a key human rights challenge in this dialogue, the dialogues are seen by both partners as of mutual benefit. It is notable that in the EU-Brazil dialogue both partners come to the dialogues with different human rights concerns, but as democracies. With criticism of the effectiveness and openness of the dialogues, the EU should look again at how the dialogues fit into the overall strategy of the Union and its member states in the promotion of human rights with third countries and assess whether the dialogues can be improved.

[1] It covers both press freedom for the Chinese media in Europe and also press freedom for European media in China.

[2] China Strategy Paper 2007-2013, Annexes, ‘the political situation’, p. 11

[3] “I urge China to release all of those who have been detained for exercising their universally recognised right to freedom of expression.”

[4] Interview with European diplomat, February 2013.