4 Jun 2015 | Events

Photo: Thomson Reuters Foundation

Six months after the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, journalists face more threats than ever before, from harassment to imprisonment to murder – since the beginning of the year, 50 journalists have been killed.

While some countries, like Norway, have scrapped blasphemy laws to strongly assert freedom of speech, others such as the UK are increasing state surveillance and censorship to “protect citizens from violence”. How can international law protect journalists in this challenging and unique context? Is it possible to strike a balance between security concerns and freedom of expression? Is the right to free speech an absolute one?

Join the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Reporters Without Borders and Paul Hastings LLP for a panel debate featuring:

- John Lloyd, Reuters Institute and Financial Times

- Prof Timothy Garton Ash, Oxford University

- Sylvie Kauffmann, Le Monde

- William Bourdon, Paris Bar and Association Sherpa

- Jodie Ginsberg, Index on Censorship

When: Monday 29 June, 6:00pm (followed by drinks reception & canapés)

Where: Edelman, London, SW1E 6QT (Map/directions)

Tickets: Free, book here

#FreeSpeechDebate

7 May 2015 | Denmark, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features

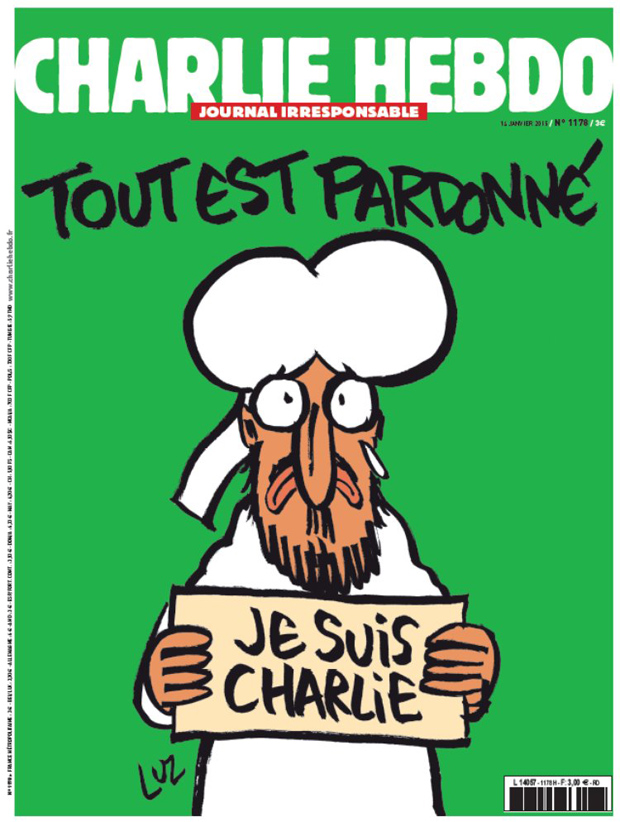

Tout est pardonne or All is forgiven, the first post attack cover of Charlie Hebdo

It’s now almost ten years since Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a set of cartoons, some of which (though by no means all) depicted the Islamic prophet Mohammed. Some were flattering, some were not. One mocked jihadist suicide bombers. Another showed a schoolboy called Mohammed calling Jyllands-Posten’s editors bigots.

The idea came after it was reported that a Swedish children’s author could not find someone to illustrate her book on the life of Mohammed. Flemming Rose of Jyllands-Posten decided to commission cartoonists to draw the apparently taboo figure.

As an exercise in taboo-busting, it was bound to be controversial. But controversial though some were (one showed the prophet as a scimitar wielding menace, another a figure with a bomb for a turban) they were not shocking enough for the Danish-based radicals who decided to make a campaign of the issue. In an astonishing act of chutzpah (there really is no other word), Ahmad Abu Laban decided to fill out a “dossier” on the cartoons with even more offensive characterisations, some of which had nothing to do with Mohammed at all. He and his colleague Ahmed Akkari took the dossier to the Middle East, apparently to prove the level of anti-Muslim hatred in Denmark. Chaos ensued. The rest, the usual line would go, is history. But that wouldn’t be true: the “rest” is very much the present, and perhaps pressing now more than at any time in the past 10 years.

One wonders if Ahmad Abu Laban quite knew what he was getting us all in to. Certainly, the man, who died in 2007, was of what is now a familiar figure in western Europe. The self-publicising Muslim spokesman: the go-to guy for a controversial quote for a press not quite sure of the heat of the flames with which they were playing. Omar Bakri Muhammad, for example, was first introduced to the British public as a ridiculous fantasist in Jon Ronson’s documentary The Tottenham Ayatollah. His proteges in al-Muhajiroun provided a steady flow of enjoyably ridiculous bogeymen such as Anjem Choudary and Abu Izzadeen, who in 2006 was given the main interview on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. Subsequent news bulletins carried his warnings of “Muslim anger” as if he were some sort of pope, rather than a fringe figure with highly dubious links.

Everyone enjoyed these outrageous figures for a while, until we realised the damage they could do. Practically every home-grown jihadist in Britain has had dealings with al-Muhajiroun. The late Laban may have known of the chaos he was about to unleash on the Middle East in 2006 with his dossier, and indeed the world ever since. He may not. His former comrade Akkari repented in 2013, saying: “I want to be clear today about the trip: It was totally wrong. At that time, I was so fascinated with this logical force in the Islamic mindset that I could not see the greater picture. I was convinced it was a fight for my faith, Islam.”

Well good, but a little late now.

Since 2005 we have been embroiled in an absurd abysmal dream. Some people draw cartoons of a long-dead religious figure. Some other people decide this has offended some sacred, though undefined, law, and so they decide that the people who drew the cartoons must be killed. Repeat. What chronic stupidity.

But of course there’s more going on here. There is more than one reason to draw or publish Mohammed drawings: from plainly making a free speech point (as many publications did after the Charlie Hebdo murders), to anti-clericalism (a la Charlie itself), to deliberate antagonism towards Muslims (a la Pamela Geller). Not all Motoons are the same.

Nor are all responses on the same spectrum. There is a world of difference between the average Muslim who may be annoyed by a portrayal of Mohammed and a jihadist who takes it upon himself to find people who have drawn these portrayals and kill them or attempt to kill them.

This is the error that has plagued the debate for the past 10 years, and came to light again in the past few weeks with PEN’s awarding of a prize to Charlie Hebdo, and the attack on a Pamela Geller-organised rally in Texas which featured a “draw Mohammed” competition.

There has been an unwitting acceptance of several dangerous ideas, chief amongst them that in order to have respect for someone as a human being, one must respect all their beliefs, and observe their taboos. But as novelist and long-time PEN activist Hari Kunzru put it: “It is not solidarity with the oppressed to offer ‘respect’ to an idea just because it’s held by some oppressed people.”

Following from this is the idea that all expression that disrespects beliefs and taboos must be driven by bigotry and racism, and that to stand against bigotry and racism is to stand against any such expression. There is a sad irony in this failure to discriminate.

On the reverse of this, some Muslims feel that free speech is now something that is being used to batter them over the head, rather than protect them. This in itself is a failure of civil society: the moment we decide everyone with a certain background and set of beliefs can be put in the “Muslim” box is the moment we ensure that those who shout loudest about those beliefs — the “extremists” — are given status. Ahmad Abu Laban, for example, claimed that his Islamic Society of Denmark represented all Danish Muslims.

So now what? As we’re approaching 10 long years of this argument, is there hope for resolution any time soon? I fear not. There can be no accommodation between those who believe in the right to free expression and those who believe “blasphemy” should carry the death sentence.

In between, if it does prove impossible not to take sides, we can at least make sure our arguments are clear and our ears are listening.

This article was posted on 7 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

1 May 2015 | Denmark, European Union, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Macedonia, mobile, News and features, Poland, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom

As we approach World Press Freedom Day, the right to freedom of expression will again be celebrated as an inalienable European value across the continent — by the public, the media and politicians alike. But to many, this will mean little more than engaging in a well trodden mental routine. We hardly consider the difficulties that freedom of expression faces in practice.

In the first part of 2015, more than a third of journalist killings in the word took place in two European countries; France and Ukraine. If it is true that Europe’s reactions to the Charlie Hebdo attack — the majority of them very emotional — were salubrious, they simultaneously gave rise to ambiguous situations. Many of the leaders that will on 3 May reaffirm their commitment free expression, supported the same message by taking part in the historic march in Paris on 11 January.

But upon seeing Angela Merkel, some were also reminded that Germany continues to treat blasphemy as a crime — as do Denmark, Spain, Poland and Greece, among others. Ireland, whose Enda Kenny was also in attendance, has a constitution which specifically mentions blasphemy and in 2010 enacted a new law against it. All these European countries defend themselves by saying that they do not apply their laws against “blasphemers”. That argument does not carry much weight when it comes to opposing those countries — Saudi Arabia, Iran, various Asian countries — that have tried to turn blasphemy into a universal crime recognised by the UN.

Spain’s Mariano Rajoy too marched in solidarity, but his government has taken steps to promote changes in the penal code that would “represent a serious threat to freedom of information, expression and the press”.

And what was Viktor Orban doing in Paris? The Hungarian president has reunified Hungary‘s public media so as to better bind them to his own party. Despite being the leader of an EU country, Orban has followed Vladimir Putin’s example. In this experimental model, the Andrei Sakharov Center and Museum is no longer ordered to close as it was in the old days, but rather fined 300,000 roubles (€5,000) for failing to register as a “foreign agent”. One day brings an announcement of compulsory registration for bloggers in Russia; another day, harassment against Russian and Hungarian NGOs perceived as “unpatriotic”.

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutohlu traveled to Paris, only to later label Charlie Hebdo’s post-attack issue a “provocation”. A reminder: Turkey is an EU candidate country where dozens of journalists have been sentenced to prison, and where various internet sites, including those that dared to reproduce some of Charlie Hebdo’s caricatures, have been blocked.

But also present at the march, were various representatives of European journalists — myself included. Just behind the Charlie Hebdo survivors, we carried a banner with the message “Nous sommes Charlie”.

Walking next to me was Franco Siddi, of the Italian National Press Federation. He talked to me about how imprisonment for defamation is still a possibility in Italy, though the European Court of Human Rights has ruled it a disproportionate punishment.

In my home country Spain too, this possibility of imprisonment remains, even if under Spanish jurisprudence freedom of expression consistently prevails over the demands of plaintiffs. In Italy, the situation is the same, yet my Italian colleagues point out that in 2014 alone, 462 journalists in the country were threatened with legal action for alleged acts of defamation. And while the current proposal for reform being considered foresees eliminating the possibility of jail time, it increases the potential fines.

This is not the only potential legal threat facing European journalists. Long before 9/11, there existed a reflexive habit of passing “urgent” laws under security pretexts, as in the UK during the most difficult years of the Northern Ireland conflict. The current model is the United States’ Patriot Act, which has recently been discussed in France. Meanwhile, in Britain and Spain are debating what free expression activists describe as “gag laws”. In Macedonia, the sentencing of the investigative journalist Tomislav Kezarovski to two years in prison under one of these security inspired laws stands out as a warning sign.

Against this worrying backdrop, across Europe journalists, freedom advocates, campaigners and even politicians are standing up for press freedom. When Gvozden Srecko Flego, member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, recently highlighted the cases of Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Azerbaijan as particularly problematic, he also suggested a countermeasure. He recommends “organising annual debates […], with the participation of journalists’ organisations and media outlets” in the respective parliaments of each state.

Media concentration, one of the most serious challenges to media pluralism and free expression in Europe, is being tackled. One proposal, which some international bodies have already accepted, would create a “Media Identity Card” requiring owners to publicly identify themselves and thus create an environment of more open and transparent media ownership.

When defending freedom of expression as a European value, we cannot allow ourselves to simply fall in into mental routines. This World Press Freedom Day we need both words and actions.

Paco Audije is a member of the Steering Committee of the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This column was posted on 1 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Apr 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

What if your job, your career, was winding up an entire nation?

That’s it. Sure, you have a column in a national newspaper. But what can you really do with it? You can’t really share your thoughts on the common toad, or tell delightful stories about your children misunderstanding foreign words, much less offer some insight into the workings of the modern world. Sure, you can chuck the odd piece of light relief in the sidebar or the basement, but that’s not what people are here for. We’ve come to your column to be thrilled by your outrageous views, and thrilled we will be.

Last time round it was people giving food to, and receiving food from, charity.

“SAY the words food bank” La Dolce ‘Opkina began, “and I am supposed to put on my concerned face and proffer up a can of beans.”

Where’s this going Katie? Where could this possibly be going?

“But all I’ve found in the back of my cupboard is two fingers. And they don’t belong to a Kit Kat.”

BOOM! Gotcha. I mean, it makes no sense. If it’s the fingers at the end of her arm she’s using, why are they in the back of the cupboard? Unless, maybe, she is SO outrageous that she keeps a special V-flipping apparatus in her cupboard, as her doctor has advised her that the constant extension and retraction of her index and middle finger was putting her in serious risk of chronic RSI. But then, if you were using it that much, you wouldn’t keep it in the back of the cupboard. You’d have it on the hall table, perhaps. Or in a little belt-mounted pouch, like a techie’s mobile phone, ready to unleash, cosh-style, upon passing do-gooders, bed-wetters, namby-pambies, oiks, poshos, hippies, liberal elitists, ignorant yokels, EUROCRATS, trendy vicars, Trots, gypsies, useless husbands, trashy wives, “gay rights” activists, lesbo-feminists and everyone else you might bump into at a reasonably-sized community festival in a reasonably-sized town.

It must be exhausting keeping track of this roll call of resentment. It must be wearing to have to be angry every week. How draining to have a public persona dedicated to hating everything and everyone.

And then there is the fact that outrage is a substance which can be addictive, but to which people can also develop a considerable tolerance. In order to keep us interested — and quite possibly to keep herself interested also — Hopkins has to keep upping the dose, until eventually we get to the point where she’s describing poor African people drowning in the sea as cockroaches and everyone suddenly stops and thinks “oh”.

The problem the serial controversialist who has nothing else to trade on faces is that the only way to go is down. The very nature of the job and the stuff you are peddling means you must, inevitably, end up overstepping the mark. In the case of Jeremy Clarkson, a carnival of boorishness ended in violence, where it had to. Hopkins seems to have survived, but she’s Zugzwanged herself: tone down the schtick and she becomes pointless; the only other move available is directly into the abyss. This is the fate of the wind-up merchant.

The exception to this rule is the satirist. The essential difference between the satirist and the controversialist is that the controversialist puts herself forward, from the beginning, as the stoic truthteller, striving alone in a world gone mad. Controversialists tend to be declinists: the world is steadily getting worse. The converse of this is the belief that at some point, usually in the period of the controversialist’s late adolescence, the world was right.

Satirists hold out no such (perverse) hope. The world is awful, the world has always been awful, and the only way to get through it is to laugh and hope we can make some tweaks around the edges. It is curious then, that from Private Eye to Charlie Hebdo, satire is often linked to campaigning journalism in the same publication.

Charlie has once again been in the news after several US-based authors refused to take part in a gala in honour of the magazine hosted by PEN American Center.

The writers’ heckles were raised by what they saw as racist cartoons run by Charlie in the past. Among these were one of a black politician portrayed as a monkey, and Nigeria girl victims of Boko Haram portrayed as “welfare queens”. Of course, at face value, these seem racist (though it is worth noting that it was not racist cartoons that saw Charlie’s staff slain: it was cartoons that refused to obey religious taboo).

What the US critics failed to acknowledge was that all satire is reactive: the cartoons did not simply spring unprompted from the cartoonists’ pens. The case of the ape cartoon was a reaction to far right portrayals of the minister, and the accompanying text very clearly mocked the Front National’s leader Marine Le Pen. As Irish novelist and Charlie columnist Robert McLiam Wilson pointed out:

“Without the snipped-off text underneath, and the knowledge of the lamentable tosh it was lampooning, of course Charlie would seem racist. It would seem racist to me too. But to strip the image of its fundamental components like this is akin to saying the incomparable Jonathan Swift was a baby-eating Nazi and that A Modest Proposal was actually a cookbook.”

Satire must toy with what it sets out to mock: otherwise it is meaningless and unintelligible. Sometimes the controversy of the likes of Hopkins and the irony of Charlie can look, at first glance, identical.

And sometimes not: While Hopkins was describing “cockroaches” drowning in the Mediterranean, Charlie was echoing the refrain of many: “A Titanic every week,” with a cartoon depicting a white woman singing My Heart Will Go On while a despairing migrant begs her to “shut up” (Ta Guelle).

Bracing? Sure. But humanising, too. As satire should be and controversialism never is.

This column was posted on 30 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org