Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”95198″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]For the second time since 2013, the United Nations (UN) Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) has issued an Opinion regarding the legality of the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajab under international human rights law.

In its second opinion, the WGAD held that the detention was not only arbitrary but also discriminatory. The 127 signatory human rights groups welcome this landmark opinion, made public on 13 August 2018, recognising the role played by human rights defenders in society and the need to protect them. We call upon the Bahraini Government to immediately release Nabeel Rajab in accordance with this latest request.

In its Opinion (A/HRC/WGAD/2018/13), the WGAD considered that the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajabcontravenes Articles 2, 3, 7, 9, 10, 11, 18 and 19 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and Articles 2, 9, 10, 14, 18, 19 and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by Bahrain in 2006. The WGAD requested the Government of Bahrain to “release Mr. Rajab immediately and accord him an enforceable right to compensation and other reparations, in accordance with international law.”

This constitutes a landmark opinion as it recognises that the detention of Mr. Nabeel Rajab – President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR), Founding Director of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), Deputy Secretary General of FIDH and a member of the Human Rights Watch Middle East and North Africa Advisory Committee – is arbitrary and in violation of international law, as it results from his exercise of the right to freedom of opinion and expression as well as freedom of thought and conscience, and furthermore constitutes “discrimination based on political or other opinion, as well as on his status as a human rights defender.” Mr. Nabeel Rajab’s detention has therefore been found arbitrary under both categories II and V as defined by the WGAD.

Mr. Nabeel Rajab was arrested on 13 June 2016 and has been detained since then by the Bahraini authorities on several freedom of expression-related charges that inherently violate his basic human rights. On 15 January 2018, the Court of Cassation upheld his two-year prison sentence, convicting him of “spreading false news and rumors about the internal situation in the Kingdom, which undermines state prestige and status” – in reference to television interviews he gave in 2015 and 2016. Most recently on 5 June 2018, the Manama Appeals Court upheld his five years’ imprisonment sentence for “disseminating false rumors in time of war”; “offending a foreign country” – in this case Saudi Arabia; and for “insulting a statutory body”, in reference to comments made on Twitter in March 2015 regarding alleged torture in Jaw prison and criticising the killing of civilians in the Yemen conflict by the Saudi Arabia-led coalition. The Twitter case will next be heard by the Court of Cassation, the final opportunity for the authorities to acquit him.

The WGAD underlined that “the penalisation of a media outlet, publishers or journalists solely for being critical of the government or the political social system espoused by the government can never be considered to be a necessary restriction of freedom of expression,” and emphasised that “no such trial of Mr. Rajab should have taken place or take place in the future.” It added that the WGAD “cannot help but notice that Mr. Rajab’s political views and convictions are clearly at the centre of the present case and that the authorities have displayed an attitude towards him that can only be characterised as discriminatory.” The WGAD added that several cases concerning Bahrain had already been brought before it in the past five years, in which WGAD “has found the Government to be in violation of its human rights obligations.” WGAD added that “under certain circumstances, widespread or systematic imprisonment or other severe deprivation of liberty in violation of the rules of international law may constitute crimes against humanity.”

Indeed, the list of those detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression and opinion in Bahrain is long and includes several prominent human rights defenders, notably Mr. Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, Dr.Abduljalil Al-Singace and Mr. Naji Fateel – whom the WGAD previously mentioned in communications to the Bahraini authorities.

Our organisations recall that this is the second time the WGAD has issued an Opinion regarding Mr. Nabeel Rajab. In its Opinion A/HRC/WGAD/2013/12adopted in December 2013, the WGAD already classified Mr. Nabeel Rajab’s detention as arbitrary as it resulted from his exercise of his universally recognised human rights and because his right to a fair trial had not been guaranteed (arbitrary detention under categories II and III as defined by the WGAD).The fact that over four years have passed since that opinion was issued, with no remedial action and while Bahrain has continued to open new prosecutions against him and others, punishing expression of critical views, demonstrates the government’s pattern of disdain for international human rights bodies.

To conclude, our organisations urge the Bahrain authorities to follow up on the WGAD’s request to conduct a country visit to Bahrain and to respect the WGAD’s opinion, by immediately and unconditionally releasing Mr. Nabeel Rajab, and dropping all charges against him. In addition, we urge the authorities to release all other human rights defenders arbitrarily detained in Bahrain and to guarantee in all circumstances their physical and psychological health.

This statement is endorsed by the following organisations:

1- ACAT Germany – Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture

2- ACAT Luxembourg

3- Access Now

4- Acción Ecológica (Ecuador)

5- Americans for Human Rights and Democracy in Bahrain – ADHRB

6- Amman Center for Human Rights Studies – ACHRS (Jordania)

7- Amnesty International

8- Anti-Discrimination Center « Memorial » (Russia)

9- Arabic Network for Human Rights Information – ANHRI (Egypt)

10- Arab Penal Reform Organisation (Egypt)

11- Armanshahr / OPEN Asia (Afghanistan)

12- ARTICLE 19

13- Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos – APRODEH (Peru)

14- Association for Defense of Human Rights – ADHR

15- Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression – AFTE (Egypt)

16- Association marocaine des droits humains – AMDH

17- Bahrain Center for Human Rights

18- Bahrain Forum for Human Rights

19- Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy – BIRD

20- Bahrain Interfaith

21- Cairo Institute for Human Rights – CIHRS

22- CARAM Asia (Malaysia)

23- Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

24- Center for Constitutional Rights (USA)

25- Center for Prisoners’ Rights (Japan)

26- Centre libanais pour les droits humains – CLDH

27- Centro de Capacitación Social de Panama

28- Centro de Derechos y Desarrollo – CEDAL (Peru)

29- Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales – CELS (Argentina)

30- Centro de Políticas Públicas y Derechos Humanos – Perú EQUIDAD

31- Centro Nicaragüense de Derechos Humanos – CENIDH (Nicaragua)

32- Centro para la Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos – CALDH (Guatemala)

33- Citizen Watch (Russia)

34- CIVICUS : World Alliance for Citizen Participation

35- Civil Society Institute – CSI (Armenia)

36- Colectivo de Abogados « José Alvear Restrepo » (Colombia)

37- Collectif des familles de disparu(e)s en Algérie – CFDA

38- Comisión de Derechos Humanos de El Salvador – CDHES

39- Comisión Ecuménica de Derechos Humanos – CEDHU (Ecuador)

40- Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (Costa Rica)

41- Comité de Acción Jurídica – CAJ (Argentina)

42- Comité Permanente por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos – CPDH (Colombia)

43- Committee for the Respect of Liberties and Human Rights in Tunisia – CRLDHT

44- Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative – CHRI (India)

45- Corporación de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos del Pueblo – CODEPU (Chile)

46- Dutch League for Human Rights – LvRM

47- European Center for Democracy and Human Rights – ECDHR (Bahrain)

48- FEMED – Fédération euro-méditerranéenne contre les disparitions forcées

49- FIDH, in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

50- Finnish League for Human Rights

51- Foundation for Human Rights Initiative – FHRI (Uganda)

52- Front Line Defenders

53- Fundación Regional de Asesoría en Derechos Humanos – INREDH (Ecuador)

54- Groupe LOTUS (DRC)

55- Gulf Center for Human Rights

56- Human Rights Association – IHD (Turkey)

57- Human Rights Association for the Assistance of Prisoners (Egypt)

58- Human Rights Center – HRIDC (Georgia)

59- Human Rights Center « Memorial » (Russia)

60- Human Rights Center « Viasna » (Belarus)

61- Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

62- Human Rights Foundation of Turkey

63- Human Rights in China

64- Human Rights Mouvement « Bir Duino Kyrgyzstan »

65- Human Rights Sentinel (Ireland)

66- Human Rights Watch

67- I’lam – Arab Center for Media Freedom, Development and Research

68- IFEX

69- IFoX Turkey – Initiative for Freedom of Expression

70- Index on Censorship

71- International Human Rights Organisation « Club des coeurs ardents » (Uzbekistan)

72- International Legal Initiative – ILI (Kazakhstan)

73- Internet Law Reform Dialogue – iLaw (Thaïland)

74- Institut Alternatives et Initiatives Citoyennes pour la Gouvernance Démocratique – I-AICGD (RDC)

75- Instituto Latinoamericano para una Sociedad y Derecho Alternativos – ILSA (Colombia)

76- Internationale Liga für Menschenrechte (Allemagne)

77- International Service for Human Rights – ISHR

78- Iraqi Al-Amal Association

79- Jousor Yemen Foundation for Development and Humanitarian Response

80- Justice for Iran

81- Justiça Global (Brasil)

82- Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law

83- Latvian Human Rights Committee

84- Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada

85- League for the Defense of Human Rights in Iran

86- League for the Defense of Human Rights – LADO Romania

87- Legal Clinic « Adilet » (Kyrgyzstan)

88- Liga lidských práv (Czech Republic)

89- Ligue burundaise des droits de l’Homme – ITEKA (Burundi)

90- Ligue des droits de l’Homme (Belgique)

91- Ligue ivoirienne des droits de l’Homme

92- Ligue sénégalaise des droits humains – LSDH

93- Ligue tchadienne des droits de l’Homme – LTDH

94- Ligue tunisienne des droits de l’Homme – LTDH

95- MADA – Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedom

96- Maharat Foundation (Lebanon)

97- Maison des droits de l’Homme du Cameroun – MDHC

98- Maldivian Democracy Network

99- MARCH Lebanon

100- Media Association for Peace – MAP (Lebanon)

101- MENA Monitoring Group

102- Metro Center for Defending Journalists’ Rights (Iraqi Kurdistan)

103- Monitoring Committee on Attacks on Lawyers – International Association of People’s Lawyers

104- Movimento Nacional de Direitos Humanos – MNDH (Brasil)

105- Mwatana Organisation for Human Rights (Yemen)

106- Norwegian PEN

107- Odhikar (Bangladesh)

108- Pakistan Press Foundation

109- PEN America

110- PEN Canada

111- PEN International

112- Promo-LEX (Moldova)

113- Public Foundation – Human Rights Center « Kylym Shamy » (Kyrgyzstan)

114- RAFTO Foundation for Human Rights

115- Réseau Doustourna (Tunisia)

116- SALAM for Democracy and Human Rights

117- Scholars at Risk

118- Sisters’ Arab Forum for Human Rights – SAF (Yemen)

119- Suara Rakyat Malaysia – SUARAM

120- Taïwan Association for Human Rights – TAHR

121- Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights – FTDES

122- Vietnam Committee for Human Rights

123- Vigilance for Democracy and the Civic State

124- World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers – WAN-IFRA

125- World Organisation Against Torture – OMCT, in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

126- Yemen Organisation for Defending Rights and Democratic Freedoms

127- Zambia Council for Social Development – ZCSD[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1535551119543-359a0849-e6f7-3″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Whenever I’m trying to fill an hour of stand-up for the Edinburgh Festival, the last thing I wonder is, “Jeez, will this set land me a spot on television?” The reasons are twofold: first, I do what makes me laugh, otherwise I get bored; second, I’ve done stand-up on television and it ain’t the apex of my career. Television producers and editors seem to have an uncanny knack for siphoning the humour out of just about anything, especially the royals, and particularly the pretty, dead ones.

Yet television comedy is held in some oddly high regard as a move up for a comic. I guess that’s because if you can’t get a TV profile going, your live shows in the provinces don’t sell very well. Why should someone in, say, Leeds, come and see you at the Varieties if you aren’t good enough to be on Les Dawson?

But to be on Les, or any television programme, your set must be “clean”. Which means few or no dirty words. Misogyny within social norms, fine, but save the word “cunt” for the wife beatings, mate. That’s right. No “cunts”, although the halls of the BBC are teeming with them. Which is sad, since “cunt” is plainly the most versatile word in the English language. It’s a verb, a noun, an adjective, and it’s really the last word on earth that, no matter how it’s used, makes my mother angry. One is also discouraged from using the word “fuck” on television, particularly as a verb. Particularly if you’re gay.

See, as an out cocksucker, there are lots of things I can get away with on stage but, on television, I’m already perceived as dangerous. TV companies treat me, in rehearsal for a taping, as though I’m retarded or a child or, worse yet, American. “Please be nice, Mr Capurro. You want the people watching to like you, don’t you? Good. We wouldn’t want everyone to think that you’re naughty, would we?”

Then they go through the litany of words I’m not supposed to use. When the show is edited and televised, other comics’ “fucks” are left in. Mine are removed. After all, being gay is dirty enough. Do I have to be dirtier with my dirty mouth?

I’m not really complaining. I’ve learned to manoeuvre my way throughout television. I can play the spiky-but-warm, take-the-cock-out-of-my-mouth-and-press-the-tongueto-my-cheek game with squeamishly positive results. Usually. But in Australia, during the taping of a “Gala” to honour a comedy festival in Melbourne, the director had a grand-mal seizure when I described Jesus as a “queerwannabe”. I saw papers fly up over the heads of a stunned, strangely silent audience. Later I found out it was the director’s script. Apparently they found him after the show, huddled in a corner, crying like a recently incarcerated prisoner who’d just taken his first “shower”.

He was afraid I’d pollute minds, I suppose. At least that’s what he told his assistant. So now, TV is promoting itself as a politically correct barometer? A sort of big-eyed nanny looking out for our sensitive sensibilities? In the six years that I’ve been performing in the UK, I’ve seen political correctness catch on like an insidious disease, like a penchant for black, like the need to oppress. Comics use the term to describe their own acts during TV meetings, and everyone around the table nods in appreciation and approval. Or are they choking? I can never tell with TV people.

Maybe they’re suffocating under a pillow of their own stupidity, since no one really understands the meaning behind political correctness, the arch, high-browed stance it panders to. The phrase was coined as a reaction to racism in the US, to respond with a sort of kindness that had been stifled when hippies disappeared from the US landscape. PC took the place of sympathy which has, since Reaganomics, had a negative, sort of “girlie” tone to it that few US politicians, especially those who served in ‘Nam, can tolerate. Being politically correct makes the user feel more in control and smarter, because they can manipulate a conversation by knowing the proper term to describe, say, an American Indian.

‘They’re actually indigenous peoples now,’ a talk-show host in

San Francisco told me while on air recently. ‘The word Indian is

too marginal.’

‘But where are they indigenous to?’

‘Well, here of course.’

‘They’re from San Francisco?’

‘No. I mean, yes. My boss’ — we were discussing his producer, Sam —

‘was born and raised here, but his parents are Cherokee from Kansas. Or

was it his grandparents?’

‘My grandfather is Italian, from Italy. What does that make me?’

‘Good in bed.’

Indigenous, tribal, quasi or semi. All these words are used to describe, politely, “the truth”. But, strangely enough, the truth is camouflaged. The white user pretends to understand the strife of the minorities, their emotional ups and downs, their need for acceptance and understanding, when all the minorities require is fair pay. I’ve never met a struggling Costa Rican labourer who was concerned that he be called a “Latino” as opposed to a “Hispanic”. He just wants to feed his family. Actually, I’ve never met a struggling Costa Rican, period. But that’s because I’m one of the annoying middle class who keep a distance from anyone who’s not like them, but who also has the time and just enough of an education to make up words and worry about who gets called what.

To the targets, the people we’re trying to protect – the downtrodden, the homeless, the forgotten – we must appear naive and bored, like nuns. It’s a lesson in tolerance that’s become intolerant. As if to say: “If you don’t think this way, if you don’t think that a black person from Bristol is better off being called Anglo-African, you’re not only wrong, you’re evil!” It’s pure fascism, plain and simple. It’s as if Guardian readers had unleashed their consciousness on everybody else, and so it’s naughty to make jokes about blacks, unless you’re black, and bad to make fun of fat people, if you’re not fat, etc. Suddenly, everyone is tiptoeing around everyone else, frightened they’ll be labelled racist because they use the word “Jew” in a punchline. Or horrified someone will think them misogynist because they think women deal better with stress.

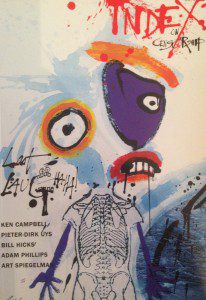

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

14 July: The power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe by Samm Farai Monro | 17 July: How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson | 21 July: Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro | 24 July: They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon | 28 July: Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera | Student reading lists: Comedy and censorship

Somehow we’ve forgotten that it’s all in how you say it. To read a brilliant stand-up comic’s act is pedantic, but to see it performed is breathtaking. That’s because what we say might be clever, but the way we arrange and self-analyse and present is where the fun comes in. Same with all those words we use. They’re not “racist” or “dangerous” by definition.

Speaking of definitions, let’s talk about the word “gay”. Lots of people I meet are concerned about what I should be called. Is it gay, which pleases the press, or queer, which pleases the hetero hip, since they think gays are trying to reclaim that word? The fact is that all those words are straight-created straight identifiers. Gay is a heterosexual concept. It’s a man who looks like a model, dresses like a model and has the brain of a model. He has disposable income, he loves to travel, and he adores – thinks he sometimes is – Madonna. He’s a teenage girl really and straights love objectifying him the -way they do teenage girls. Or the way they do infants. Try watching a diaper commercial with the sound off. It’s like porn. You’ll think you’re in a bar in Amsterdam.

I’m about as comfortable with the word “gay” as I am with kiddy porn. I’d prefer to be called a comic. Not a gay comic. Not a queer comic. Not even a gay, queer comic, or a fierce comic, or an alternative comic. It’s just the mainstream trying to pigeonhole me, trying to say, OK, he’s gay, so it’s OK to laugh at his stuff about gays. Which is why, partially, in my act, I make fun of the Holocaust by saying “Holocaust, schmolocaust, can’t they whine about something else?”

The line is meant to be ambiguous, initially. It’s meant to start big, and then the actual subject gets small, as I discuss ignorance about the pink triangle as a symbol of oppression, which has since been turned into a fashion accessory. Like the red ribbon, it makes the PC brigade feel like they’ve done their part to ease hatred in the world by adorning their lapel with a pin. When pressed, they’re not even sure what oppression they’re curing, or why they should cure oppression, or how they’re oppressed.

But if you make fun of that triangle, or this Queen Mum, or that dead Princess, suddenly you’re — why mince — I’m the bad guy. I’ve broken away from the pack. I’m not acting like a good little queer should. I’m not being silent about issues that don’t concern a modern gay man, like hair-dos and don’ts. I’m being aggressive, I’m on to. And those straights, those in charge, the folks looking after “my minority group”, don’t like rolling over.

Nor are some cocksucking idiots happy about being bottom-feeders either. Which is why I come out against abortion in my act, and in support of the death penalty since, in the US at least, the two go hand in manicured hand. There I go, losing my last supporters: young women and single gay men. How can I say: “If you wanna talk Holocaust, how about abortion, ladies? 50 million. Can you maybe keep your legs together?”

That is truly evil. No, not really evil. Just wrong. Why? Particularly when I’m only opposed to abortion as a contraceptive device. Who decides what I can and cannot say? Isn’t it the people that aren’t listening? If I’ve got a good joke about it, a well-thought-out attack and a point to make, why is it bad? Why is the world dumbing down almost as fast as Woody Allen’s films? Why does it bother me? Why not just do my same old weenie jokes, keep playing the clubs and sleep with closeted straight comics? Just doing those three things – particularly the last – would keep me very busy and distracted, which is what “life” is all about.

But I imagine that when people go for a night out, they wanna see something different. It’s a big deal finding a babysitter, getting a cab, grabbing a bite and sitting your tired ass into a pricey seat to hear some faggot rattle on for an hour. So I try to offer them a unique perspective. One that might seem overwrought, desperate, or strangely effortless, but one that might make them look at, say, an Elton John photo just a bit differently next time

Look, it’s not my job to find anyone’s comfort zones. I don’t give a shit what people like, or think they like, or want to like. I’m not a revolutionary. I’m just a joke writer with an hour to kill, who wants to elevate the level of intelligence in my act to at least that of the audience.

If in doing that, I get a beer thrown at me or I lose a “friend” (read: jealous comic) then so be it. In the meantime, I’ll keep fending off my growing array of fans that are sick and tired of being lied to and patronised.

Gosh, get her! I mean me. Get me, sounding all holier than, well, everybody. Strangely enough, the more I find my voice on stage, the more serious comedy becomes for me. Maybe I should go back to telling those “Americans are so silly” jokes before I lose my mind, and throw all my papers up in the air.

Scott Capurro is a San Francisco-based stand-up whose performance at the

Edinburgh Fringe in August ended in uproar after he ‘made jokes’ about the

Holocaust. His book, Fowl Play, was published by Headline in September

1999

This article is from the November/December 2000 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

Walls are plastered with campaign posters ahead of the 14 Feb elections in Nigeria. (Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung/Flickr)

Update: This article was posted before Nigerian election authorities postponed the polls until March 28, 2015.

As Nigeria’s 14 February general election approaches, the menace of Boko Haram has intensified. Attacks are more frequent and brutal. No Nigerian is entirely safe.

In Baga, a community in Borno state in Nigeria’s north-east, over 2000 people were reportedly killed in a single attack in January. Boko Haram is easily one of the world’s deadliest terror groups — a group that slit 61 school boys’ throats in a raid; that straps bombs on 10 year-olds; that has kept 276 school girls abducted for almost a year and is abducting more; that has killed over 30,000 Nigerians and left over 3 million displaced.

The group now controls a land mass the size of Costa Rica, collects taxes, has its own emirs and has declared a caliphate incorporating parts of Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroon. On 25 January 2014, the group, in a very daring move, made efforts to seize Maiduguri, the Borno state capital.

Boko Haram’s activities are not restricted to the north-eastern part of Nigeria as generally believed. The attacks on the UN headquarters and police headquarters in Abuja, the federal capital city, and several other deadly assaults occurred in Nigeria’s north central states.

The group’s attacks have stagnated economic growth in the north east and weakened diplomatic relations between Nigeria and neighbouring countries. In an escalation, Chadian troops have attacked Boko Haram positions in Nigeria, the BBC reported on 3 Feb.

Local views

While the group has consistently reiterated that it is out to Islamise Nigeria, a good number of Nigerians — Muslims and Christians alike — find this implausible.

Initially it was a convincing strategy because the group targeted mostly Christian places of worship and a few government institutions. Over time, however, the attacks became more random and less deliberate. Individuals of different ethnic groups and religious convictions were dragged off buses and killed in vile operations in broad daylight, typically lasting several hours with no interruption from security agencies. Entire villages have been ransacked regardless of religion or ethnicity.

Some Nigerian Christians however, opt to stick with Boko Haram’s initial script, pointing out that the group’s attacks bear a close resemblance to those of ISIS, known to have a very low tolerance for people of other faiths and liberal Muslims. A handful of northern Muslims agree with this line of thought.

There are also those who believe the group is being funded by some members of the northern Islamic political elite for selfish gain. Such theories appear to have basis in fact. At least one sitting senator and a former governor of Borno state, have been closely linked at various times to the group. Why none of them have been investigated leaves most Nigerians baffled.

There are other theories about the rise of Boko Haram that pin the blame on the government. This line of reasoning cites the president’s southern heritage for a lack of interest with the violence in the north. Southerners are seen to be taking vengeance for the loss of lives and property suffered at the hands of northerners during the Biafran War of 1967. Boko Haram also presents another route for siphoning Nigeria’s funds into private accounts.

The accusations of a self-acclaimed Australian “negotiator”, Stephen Davies, that Nigeria’s former Chief of Defence Staff, Major General Azubuike Ihejirika, a southern Christian, was actively involved in funding Boko Haram activities while working to undermine Nigeria’s army, resonated with many Nigerians of northern extraction who believe the current administration is out to cripple the region. Some southerners, on the other hand, say the northerners brought Boko Haram upon themselves and should therefore reap the fruits of their folly. Such people neither see Boko Haram as a national threat nor believe there is any truth to some of the harrowing stories coming out of the north, viewing them simply as an attempt to frustrate President Goodluck Jonathan, himself a southern Christian, out of office.

Media silence

The media in Nigeria, despite their seeming independence, are divided along political lines depending on ownership. Government media are biased in favour of the government while the private media lean towards the political loyalty of the owner. Accountability to the citizens is low.

Investigative reporting on the situation in the north by local media is limited. Local journalists are quick to point out that they lack the support of their respective organizations to report these stories. The lack of insurance, social benefits or recognition in the event of death is also cited as reasons for this reluctance. Indeed several media houses have been attacked without any response from the authorities.

Nigerians will often quote foreign press in authenticating their stories, since other local sources are generally viewed as suspect. For instance, while authorities put the deaths in Baga at 150–based primarily on guess work, foreign media reported 2,000 deaths based on satellite imagery and interviews with some who escaped the carnage.

The military appears helpless. Stories are told of soldiers who trade their arms for mufti from the locals or wear civilian clothes under their uniforms in order to enhance escape in the event of an attack. Boko Haram is considered more brutal to soldiers.

In a recent interview with CNN anonymous soldiers said that supplies and incentives are low, morale is lacking and wounded soldiers are made to pay for their treatment. A spokesperson for the military has since denied these allegations, labelling the claims “satanic”. There has been at least one incident of mutiny among the troops in the north.

Most Nigerians see BH as a threat to Nigeria’s development and would want an end to the menace. Life is now altered. Roads that were four lanes in the past are now narrowed to a lane or two in areas with a heavy government presence. The roads in the country are heavily guarded, and a general sense of unease and fear rules especially in northern Nigeria.

Will Nigerians speak to the situation in the coming presidential elections? Tough question. Ordinarily yes, Nigerians will respond by voting out a government that has shown a complete lack of determination, political will or focus to counter Boko Haram.

But this is Nigeria. The political elite have successfully used religion and ethnicity to divide the populace, wherein voting, even if it counts, will be coloured by ethnicity and religion. Even so, for the first time in the annals of Nigeria’s history, the president’s campaign convoy has been repeatedly stoned.

February 14, Valentine’s day, Nigeria’s Presidential elections day, will tell where the love truly lies.

This article was originally published on 4 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org