Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Mr. Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, Mr. David Kaye, Mr. Joseph Cannataci, Mr. Maina Kiai, Mr. Michel Forst, Ms. Faith Pansy Tlakula, and Ms. Reine Alapini-Gansou

cc: African Union

African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) Secretariat

Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa Secretariat

Domestic & International Election Observer Missions to the Republic of Uganda

East African Community Secretariat

International Conference on the Great Lakes Region Secretariat

New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) Secretariat

Uganda Communications Commission

Uganda Electoral Commission

Uganda Ministry of Information and Communications Technology

23 February 2016

Re: Internet shutdown in Uganda and elections

Your Excellencies,

We are writing to urgently request your immediate action to condemn the internet shutdown in Uganda, and to prevent any systematic or targeted attacks on democracy and freedom of expression in other African nations during forthcoming elections in 2016. [1]

On February 18, Ugandan internet users detected an internet outage affecting Twitter, Facebook, and other communications platforms. [2] According to the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), blocking was carried out on orders of the Electoral Commission, for security reasons. [3] The shutdown coincided with voting for the presidential election, and remained in place until the afternoon of Sunday, February 21. During this period, two presidential candidates were detained under house arrest. [4] The telco MTN Uganda confirmed the UCC directed it to block “Social Media and Mobile Money services due to a threat to Public Order & Safety.” [5] The blocking order also affected the telcos Airtel, Smile, Vodafone, and Africel. President Museveni admitted to journalists on February 18 that he had ordered the block because “steps must be taken for security to stop so many (social media users from) getting in trouble; it is temporary because some people use those pathways for telling lies.” [6]

Research shows that internet shutdowns and state violence go hand in hand. [7] Shutdowns disrupt the free flow of information and create a cover of darkness that allows state repression to occur without scrutiny. Worryingly, Uganda has joined an alarming global trend of government-mandated shutdowns during elections, a practice that many African Union member governments have recently adopted, including: Burundi, Congo-Brazzaville, Egypt, Sudan, the Central African Republic, Niger, Democratic Republic of Congo. [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]

Internet shutdowns — with governments ordering the suspension or throttling of entire networks, often during elections or public protests — must never be allowed to become the new normal. Justified for public safety purposes, shutdowns instead cut off access to vital information, e-financing, and emergency services, plunging whole societies into fear and destabilizing the internet’s power to support small business livelihoods and drive economic development.

Uganda’s shutdown occurred as more than 25 African Union member countries are preparing to conduct presidential, local, general or parliamentary elections. [15]

A growing body of jurisprudence declares shutdowns to violate international law. In 2015, various experts from the United Nations (UN) Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Organization of American States (OAS), and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), issued an historic statement declaring that internet “kill switches” can never be justified under international human rights law, even in times of conflict. [16] General Comment 34 of the UN Human Rights Committee, the official interpreter of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, emphasizes that restrictions on speech online must be strictly necessary and proportionate to achieve a legitimate purpose. Shutdowns disproportionately impact all users, and unnecessarily restrict access to information and emergency services communications during crucial moments.

The internet has enabled significant advances in health, education, and creativity, and it is now essential to fully realize human rights including participation in elections and access to information.

We humbly request that you use the vital positions of your good offices to:

We are happy to assist you in any of these matters.

Sincerely,

Access Now

African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights Studies (ACDHRS)

Association for Progressive Communications (APC)

Article 19 East Africa

Chapter Four Uganda

CIPESA

CIVICUS

Committee to Protect Journalists

DefendDefenders (The East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Project)

Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

Global Partners Digital

Hivos East Africa

ifreedom Uganda

Index on Censorship

Integrating Livelihoods thru Communication Information Technology (ILICIT Africa)

International Commission of Jurists Kenya

ISOC Uganda

KICTANet (Kenya ICT Action Network)

Media Rights Agenda

Paradigm Initiative Nigeria

The African Media Initiative (AMI)

Unwanted Witness

Web We Want Foundation

Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET)

Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum

Endnotes

[1] Uganda election: Facebook and Whatsapp blocked’ (BBC, 18 February 2016) <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-35601220> accessed 18 February 2016.

[2] Omar Mohammed, ‘Twitter and Facebook are blocked in Uganda as the country goes to the polls’ (Quartz Africa, 18 February 2016) <http://qz.com/619188/ugandan-citizens-say-twitter-and-facebook-have-been-blocked-as-the-election-gets-underway/> accessed 18 February 2016.

[3] Uganda blocks social media for ‘security reasons’, polls delayed over late voting material delivery (The Star, 18 February 2016) <http://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2016/02/18/uganda-blocks-social-media-for-security-reasons-polls-delayed-over_c1297431> accessed 18 February 2016.

[4] Brian Duggan, “Uganda shuts down social media; candidates arrested on election day” (CNN, 18 February 2016) <http://www.cnn.com/2016/02/18/world/uganda-election-social-media-shutdown/> accessed 22 February 2016.

[5] MTN Uganda <https://twitter.com/mtnug/status/700286134262353920> accessed 22 February 2016.

[6] Tabu Batugira, “Yoweri Museveni explains social media, mobile money shutdown” (Daily Nation, February 18, 2016) <http://www.nation.co.ke/news/Yoweri-Museveni-explains-social-media-mobile-money-shutdown/-/1056/3083032/-/8h5ykhz/-/index.html> accessed 22 February 2016.

[7] Sarah Myers West, ‘Research Shows Internet Shutdowns and State Violence Go Hand in Hand in Syria’ (Electronic Frontier Foundation, 1 July 2015)

<https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2015/06/research-shows-internet-shutdowns-and-state-violence-go-hand-hand-syria> accessed 18 February 2016.

[8] ‘Access urges UN and African Union experts to take action on Burundi internet shutdown’ (Access Now 29 April 2015) <https://www.accessnow.org/access-urges-un-and-african-union-experts-to-take-action-on-burundi-interne/> accessed 18 February 2016.

[9] Deji Olukotun, ‘Government may have ordered internet shutdown in Congo-Brazzaville’ (Access Now 20 October 2015) <https://www.accessnow.org/government-may-have-ordered-internet-shutdown-in-congo-brazzaville/> accessed 18 February 2016.

[10] Deji Olukotun and Peter Micek, ‘Five years later: the internet shutdown that rocked Egypt’ (Access Now 21 January 2016) <https://www.accessnow.org/five-years-later-the-internet-shutdown-that-rocked-egypt/> accessed 18 February 2016.

[11] Peter Micek, ‘Update: Mass internet shutdown in Sudan follows days of protest’ (Access Now, 15 October 2013) <https://www.accessnow.org/mass-internet-shutdown-in-sudan-follows-days-of-protest/> accessed 18 February 2016.

[12] Peter Micek, ‘Access submits evidence to International Criminal Court on net shutdown in Central African Republic’(Access Now 17 February 2015) <https://www.accessnow.org/evidence-international-criminal-court-net-shutdown-in-central-african-repub/> accessed 18 February 2016.

[13] ‘Niger resorts to blocking in wake of violent protests against Charlie Hebdo cartoons.’ (Access Now Facebook page 26 January 2015) <https://www.facebook.com/accessnow/posts/10153030213288480> accessed 18 February 2016.

[14] Peter Micek, (Access Now 23 January 2015) ‘Violating International Law, DRC Orders Telcos to Cease Communications Services’ <https://www.accessnow.org/violating-international-law-drc-orders-telcos-vodafone-millicon-airtel/> accessed 18 February 2016.

[15] Confirmed elections in Africa in 2016 include: Central African Republic (14th February), Uganda (18th February), Comoros and Niger (21st February), Rwanda (22nd -27th February), Cape Verde (TBC February), Benin (6th-13th March), Niger, Tanzania and Congo (20th March), Rwanda (22nd March), Chad (10th April), Sudan (11th April), Djibouti (TBC April), Niger (9th May), Burkina Faso (22nd May), Senegal (TBC May), Sao Tome and Principe (TBC July), Zambia (11th July), Cape Verde (TBC August), Tunisia (30th October), Ghana (7th November), Democratic Republic of Congo (27th November), Equatorial Guinea (TBC November), Gambia (1st December), Sudan, and Cote d’Ivoire (TBC December). Other elections without confirmed dates are scheduled to occur in Sierra Leone, Mauritania, Libya, Mali, Guinea, Rwanda, Somalia, and Gabon.

[16] Peter Micek, (Access Now 4 May 2015) ‘Internet kill switches are a violation of human rights law, declare major UN and rights experts’ <https://www.accessnow.org/blog/2015/05/04/internet-kill-switches-are-a-violation-of-human-rights-law-declare-major-un> accessed 18 February 2016.

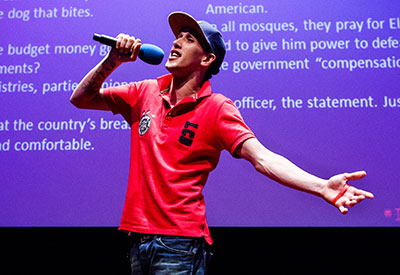

Rafael Marques de Morais, Safa Al Ahmad, Amran Abdundi, Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat and Tamas Bodokuy (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

When times get tough, freedom of expression can quickly fall down the list of priorities. But it is exactly in these circumstances when the ability to communicate and express yourself is most important. For this reason, we continue to draw inspiration from last year’s Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards fellows and their struggles to keep freedom of expression alive and well.

As we look forward to the 2016 Index awards, here is our latest reminder of just how important a job our past winners do in the fight for free speech.

Tamas Bodoky, Atlatszo.hu / Digital Activism

Last year was a positive one for the Hungarian investigative journalism site and NGO Atlatszo. The site’s yearly report reveals that funding was on the up and readership remained high.

The report also outlines the site’s main investigations over the course of 2015, which include exposing state corruption, public budget spending, irregularity within EU funding and land lease and privatisation controversies.

The website’s project for tracking down hate crime gained traction in 2014, and last year expanded to include “violent football hooligan groups and clergymen, who are close to the far-right,” the site’s executive director Tamas Bodoky told Index on Censorship.

“Unfortunately, some people became very hostile to our refugee crisis reporting last year, saying things like ‘go to hell, Atlatszo, for helping them’,” he added.

Atlatszo made 90 freedom of information requests as an organisation — plus hundreds of requests submitted by staff in their own names. Around 50% of Atlatszo’s requests were at least partially granted. Of those that weren’t, the site has initiated court proceedings to obtain the information, with almost half so far being successful, with several others pending.

Going forward, Atlatszo has plans to expand by working with more bloggers and developing a new website allowing Hungarian citizens to “question representatives of Hungary in EU, members of the Hungarian Parliament and — in the long run — representatives of the local governments”. The kepviselom.hu (my representative) project is currently seeking donors through crowdfunding.

“The Index award certainly helped get more international recognition over the last year,” Bodoky said. “As a very small news organisation, we constantly struggle for visibility, and Index on Censorship was instrumental in raising the visibility of our cause.”

Safa Al Ahmad / Journalism

With the political crisis in Yemen steadily getting worse since last year, any plans Safa Al Ahmed had to switch focus were sidelined as she returned to the battle-scarred country.

With the political crisis in Yemen steadily getting worse since last year, any plans Safa Al Ahmed had to switch focus were sidelined as she returned to the battle-scarred country.

“I filmed events in Aden and then Taiz, which is currently besieged,” the award-winning journalist told Index on Censorship. “I’m going to be producing two separate films for both cities because north and south have very different dynamics.”

Actually getting into Yemen is a real task in itself. Al Ahmed and her crew took a boat from Djibouti to Aden, which took 34 hours, and then travelled for another day off-road and across mountainous terrain, passing snipers along the way.

With the execution of the prominent Shia cleric Nimr al-Nimr, Al Ahmad’s own country Saudi Arabia was briefly catapulted back into international focus at the start of 2016, but it didn’t last. “There is very little investigative journalism being done on the ground, which makes reporting difficult as there isn’t very much to build on,” Al Ahmed says.

Citing the flogging of blogger Raif Badawi as an example of how brutal the Saudi regime is of critical voices, Al Ahmad describes the state of free speech in Saudi Arabia as “frightening”. “The government have passed really wide rulings and laws so they can stop or arrest anyone for the simplest of reasons, including talking about the war in Yemen, which has been banned,” she explains.

The big difference between now and 2014 is that people are currently receiving death sentences, which is “a whole different level of intimidation”.

Mouad Belghouat aka El Haqed / Arts

Last time we caught up with Moroccan rapper Mouad Belghouat, aka El Haqed, in October, he was in his home country keeping a low profile, while looking forward to performances in Florence, Italy, and at the 25th anniversary of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights in Brussels. Since November 2015, he has been living in Belgium, having applied for refugee status.

Last time we caught up with Moroccan rapper Mouad Belghouat, aka El Haqed, in October, he was in his home country keeping a low profile, while looking forward to performances in Florence, Italy, and at the 25th anniversary of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights in Brussels. Since November 2015, he has been living in Belgium, having applied for refugee status.

“In Morocco I felt threatened and under constant control,” he told Index this month. “It’s been hard, because already I miss the place where I grew up; I miss my family and my friends.” The situation in Morocco “deteriorates more and more every day, at all levels”, he explains, but vows one day to return.

He has now been cleared to work in Belgium, and has also turned his attention to creating more music. “I’m trying to finish the album I’ve been writing based on my experiences in prison in Morocco, and — as the last set of concerts have gone so well — I will be performing in Belgium in March and am looking to tour Norway come April.”

There are also plans for a biography based on his experiences from 2011, when his music became an anthem for many Moroccans involved in the Arab Spring, right up to his persecution at the hands of the authorities, right up to his eventual self-imposed exile.

As for the Index award, he said: “Through Index, I met many great people from all over the world who share the same principles as me, and word of my case has spanned the breadth of the world.”

Amran Abdundi / Campaigning

During our last conversation with Amran Abdundi, we discussed the attack in her native Kenya by Al-Shabaab linked terrorists on Garissa University College, in which 148 people were murdered. Abdundi, who knows many students from the college, immediately joined with other women leaders to organise strong community protests against Al-Shabaab.

During our last conversation with Amran Abdundi, we discussed the attack in her native Kenya by Al-Shabaab linked terrorists on Garissa University College, in which 148 people were murdered. Abdundi, who knows many students from the college, immediately joined with other women leaders to organise strong community protests against Al-Shabaab.

Last month, Abdundi attended the re-opening ceremony for Garissa University College. “I was happy to meet victims who I offered counselling to after the attack, and see them now back on their feet, ready to study and achieve their dreams,” she told Index.

She has also been busy recently with the upcoming launch of the new Frontier Indigenous Network website and implementing a new social media strategy to foster better connections between Kenyan women and the rest of the world.

As part of this new development plan, 2016 is packed with new projects, including an education programme on non-violence to counter violent extremism and radicalisation. The project will bring together Christians and Muslims together in “preaching peace and reconciliation”.

“All of this wouldn’t have been possible without the Index award and the support I have received from Index on Censorship, which led me to meet key individuals, such as Kenya’s woman minister, Anne Waigiru.”

Rafael Marques de Morais / Journalism

President José Eduardo dos Santos has been in power in Angola for over 35 years and his regime faces criticism on many fronts for, among other things, land grabbing, human rights abuses in Angolan prisons and the divvying up of the country’s resources to his family “like it was their inheritance”. These are just some of the issues Index award winner Rafael Marques de Morais is focusing on his activism and writing.

President José Eduardo dos Santos has been in power in Angola for over 35 years and his regime faces criticism on many fronts for, among other things, land grabbing, human rights abuses in Angolan prisons and the divvying up of the country’s resources to his family “like it was their inheritance”. These are just some of the issues Index award winner Rafael Marques de Morais is focusing on his activism and writing.

“This kind of work generates all sorts of troubles, because when you speak out against the president, you become suspect,” de Morais told Index on Censorship.

Being a high-profile activist within the country, there is a misconception that de Morais doesn’t feel the full force of the regime. “I might be ‘free’ but I can’t go anywhere; when I went for a drink recently the person I was with noticed we were being watched,” he explains. When he tried to enter a courtroom in December to observe the case involving the 15 Angolan bloggers now under house arrest, he was denied access. “Immediately the news on television was that I tried to enter the court illegally, because being high profile, the main thing they can attack is your reputation.”

Coupled with the ongoing economic crisis in Angola preventing citizens from taking money out of the bank, times are tough. “How is one supposed to survive and keep going?” he asks.

But go on he does. The attention from home and abroad, including that generated by the Index award, have provided some solace. “It’s always refreshing to know that people are interested,” he explains. “The award provides great encouragement for one to keep going.”

“But that’s it. The next day, you are back to struggling for survival.”

The Index on Censorship 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards shortlist has been announced.

The Ethiopian government bolstered its image as a global leader in stifling internal dissent last week with the convictions of 24 prominent critics on conspiracy to commit acts of terrorism charges. Eskinder Nega, an influential journalist repeatedly detained over past years for challenging regime policy, is among those awaiting sentence, along with five other journalists tried in absentia.

Employing new anti-terrorism legislation, widely condemned by rights groups as draconian, the move reinforces Ethiopia’s status as one of the most inhospitable environments for press liberty worldwide.

“Freedom of speech can be limited when it is used to undermine security and not used for the public interest,” said Judge Endeshaw Adane in court. The dissidents face potential life terms in prison.

The 27 June ruling unleashed an outcry from rights groups, who condemned the charges as part of a systematic campaign to eliminate political and social opposition.

Analysts say those convicted acted in accordance with rights enshrined in the Ethiopian constitution and international law statutes.

“These individuals were targeted for peaceful activities and calling for reform to take place,” said Claire Beston, Ethiopia researcher at Amnesty International, while emphasising the need to alter the language of the anti-terrorism bill. “Since this legislation was passed, but particularly over last 12 to 18 months, there have been significantly more incidents of suppressing dissent.”

Since claiming power in 1991, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front-led government has treated the independent press as a threat. The Nega case prosecutor claimed those convicted have connections to outlawed organisations, such as US-based Ginbot 7, an organisation that calls for the overthrown of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi’s regime.

Former US Ambassador to Ethiopia and Horn of Africa expert, David Shinn, says the convictions do not represent a significant change in the government’s approach towards the press. Shinn termed the effort to stifle media voices “cyclical”.

“There’s obviously been a long history of cracking down on journalists in Ethiopia,” said Shinn, who served as ambassador from 1996 to 1999. “It goes back to the very beginning of press reporting in the country.”

In mid-June, prominent US Senator Patrick Leahy threatened to withhold USD $500,000 of military aid to Ethiopia should the country fail to improve its human rights record. Considering the relatively small sum, the gesture is merely symbolic and world powers seem reluctant to implement stern measures to curb the harassment of dissidents.

With the US as a primary backer, Ethiopia is a beneficiary of billions of dollars of military and humanitarian aid on an annual basis. Beston says imposing financial restrictions on assistance is an effective yet severely under-utilised mechanism to ensure improvement in the government’s attitude towards human rights.

“There’s been no strong response, no significant criticism… there are no questions being asked about the humanitarian situation in the country,” said Beston. “[Foreign powers] have influence and they should be asking questions about the ever-decreasing space for press freedom, among other things, in the country.”

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) claims Ethiopia sends more reporters into exile than any other country across the globe. Those that remain are shackled and isolated. The government, according to critics, recently unveiled a sophisticated new technology to censor web content, dubbed the Deep Packet Inspection. CPJ claims the filter blocks heavily trafficked local and international sites, and places Ethiopia in the censorship lead among African countries.

“As the technology develops in order to assist civilians and activists to get around censorship, the government is introducing additional technology to prevent that,” said Beston. “There’s also very high level of surveillance. People are scared of sending emails with any type of criticism.”

Since November Ethiopian courts have charged 11 journalists with terrorism, including two Swedish reporters apprehended in the volatile Ogaden region of the country. The charges triggered a diplomatic row but the journalists remain in detention.

The government prevents all independent observers from entering Ogaden, a large swathe of territory bordering Djibouti, Somalia and Kenya. The Ethiopian Army has deployed in the region in recent years to quash local rebel groups, primarily the Ogaden National Liberation Front. Despite the media blockade, rights groups claim both sides commit atrocities. The situation there is steadily gaining attention.

“The accusations certainly require media and other independent investigations,” said Beston. “The US should be pushing for that. They should be ensuring their aid is not used to commit crimes that violate international law.”

Over recent years, however, the Zenawi regime has provided a critical ally to the US and European powers. In a vitally important area prone to unrest, the Ethiopian army frequently engages in peacekeeping missions and military campaigns in conjunction with global partners.

“You go back to the issue of how far you can push [human rights abuses] and risk losing what the Ethiopians do in the region,” said Shinn. “They were asked to step in in Abyei as peacekeepers and they did that, like any other number of incidents where they’ve done similar things in the region.”

But to innumerable Ethiopians, last week’s arguably erroneous convictions will likely serve as a deterrent to push for reform in a country seemingly in dire need of it.

“The evidence presented…criminalized their individual rights to freedom of expression and their legal conduct as journalists and political oppositionists,” said Beston.

Brian Dabbs is an internationally published print and photo journalist based in Nairobi

The arrest and detention of a Kiwi journalist lays bare the risks and calculations taken by foreign journalists in Yemen. Iona Craig reports from Sana’a

The arrest and detention of a Kiwi journalist lays bare the risks and calculations taken by foreign journalists in Yemen. Iona Craig reports from Sana’a