Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A Russian fan at the Euro 2020 match between Belgium and Russia. Stanislav Krasilnikov/Tass/PA Images

In celebration of one of football’s biggest international tournaments, here is Index’s guide to the free speech Euros. Who comes out on top as the nation with the worst record on free speech?

It’s simple, the worst is ranked first.

We continue today with Group B, which plays the deciding matches of the group stages today.

Unlike their relatively miserable performances on the football pitch, Russia can approach this particular contest as the clear favourites.

The group would be locked up after the first two games, with some sensational play from their three talismans: disinformation, oppressive legislation and attacks on independent media.

Russian disinformation, through the use of social media bots and troll factories, is well known, as is their persistent meddling in foreign elections which infringes on the rights of many to exercise their right to vote based on clear information.

Putin’s Russia has increased its attacks on free speech ever since the 2011 protests over a flawed election process. When protests arose once again all over the country in January 2021 over the detention of former opposition leader Alexei Navalny, over 10,000 people were arrested across the country, with many protests violently dispersed.

Police in the country must first be warned before a protest takes place. A single-person picket is the only form of protest that does not have this requirement. Nevertheless, 388 people were detained in Russia for this very act in the first half of 2020 alone, despite not needing to notify the authorities that eventually arrested them.

Human rights organisation, the Council of Europe (COE), expressed its concerns over Russian authorities’ reactions to the Navalny protests.

Commissioner Dunja Mijatović said: “This disregard for human rights, democracy and the rule of law is unfortunately not a new phenomenon in a country where human rights defenders, journalists and civil society are regularly harassed, including through highly questionable judicial decisions.”

Unfortunately, journalists attempting to monitor these appalling free speech violations face a squeeze on their platforms. Independent media is being deliberately targeted. Popular news site Meduza, for example, is under threat from Russia’s ‘foreign agents’ law.

The law, which free expression non-profit Reporters Without Borders describes as “nonsensical and incomprehensible”, means that organisations with dissenting opinions receiving donations from abroad are deemed to be “foreign agents”.

Those who do not register as foreign agents can receive up to five years’ imprisonment.

Being added to the register causes advertisers to drop out, meaning that revenue for the news sites drops dramatically. Meduza were forces to cut staff salaries by between 30 to 50 per cent.

Belgium is relatively successful in combating attacks on free speech. It does, however, make such attacks arguably more of a shock to the system than it may do elsewhere.

The coronavirus pandemic was, of course, a trying time for governments everywhere. But troubling times do not give leaders a mandate to ignore public scrutiny and questioning from journalists.

Alexandre Penasse, editor of news site Kairos, was banned from press conferences after being accused by the prime minister of provocation, while cartoonist Stephen Degryse received online threats after a cartoon that showed the Chinese flag with biohazard symbols instead of stars.

Incidents tend to be spaced apart, but notable. In 2020, journalist Jérémy Audouard was arrested when filming a Black Lives Matter protest. According to the Council of Europe “The policeman tried several times to prevent the journalist, who was showing his press card, from filming the violent arrest of a protester lying on the ground by six policemen.”

There is an interesting debate around holocaust denial, however and it is perhaps the issue most indicative of Belgium’s stance on free speech.

Holocaust denial, abhorrent as it may be, is protected speech in most countries with freedom of expression. It is at least accepted as a view that people are entitled to, however ridiculous and harmful such views are.

The law means that anyone who chooses to “deny, play down, justify or approve of the genocide committed by the German National Socialist regime during the Second World War” can be imprisoned or fined.

Belgium has also considered laws that would make similar denials of genocides, such as the Rwandan and Armenian genocides respectively, but was unable to pursue this due to the protestations of some in the Belgian senate and Turkish communities. It could be argued that in some areas, it is hard to establish what constitutes as ‘denial’, therefore, choosing to ban such views is problematic and could set an unwelcome precedent for future law making regarding free speech.

Comparable legal propositions have reared over the years. In 2012, fines were introduced for using offensive language. Then mayor Freddy Thielemans was quoted as saying “Any form of insult is from now on [is] punishable, whether it be racist, homophobic or otherwise”.

Denmark has one of the best records on free speech in the world and it is protected in the constitution. It makes a strong case to be the lowest ranked team in the tournament in terms of free speech violations. It is perhaps unfortunate then, that they were drawn in a group with their fellow Scandinavians.

Nevertheless, no country’s record on free speech is perfect and there have been some concerning cases in the country over the last few years.

2013 saw a contentious bill approved by the Danish Parliament “reduced the availability of documents prepared”, according to freedominfo.org. Essentially, it was argued that this was a restriction of freedom of information requests which are vital tool for journalists seeking to garner correct and useful information.

Acts against freedom of speech tend to be individual acts, rather than a persistent agenda.

Impartial media is vital to upholding democratic values in a state. But, in 2018, public service broadcaster DR was subjected to a funding cut of 20 per cent by the right-wing coalition government.

DR were forced to cut around 400 jobs, according to the European Federation of Journalists, an act that was described as “revenge” at the time.

There have been improvements elsewhere. In 2017, Denmark scrapped its 337-year-old blasphemy law, which previously forbade public insults of religion. At the time, it was the only Scandinavian country to have such a law. According to The Guardian, MP Bruno Jerup said at the time: “Religion should not dictate what is allowed and what is forbidden to say publicly”.

The change to the law was controversial: a Danish man who filmed himself burning the Quran in 2015 would have faced a blasphemy trial before the law was scrapped.

In 2020, Danish illustrator Niels Bo Bojesen was working for daily newspaper Jyllands-Posten and replaced the stars of the Chinese flag with symbols of the coronavirus.

Jyllands-Posten refused to issue the apology the Chinese embassy demanded.

The Council of Europe has reported no new violations of media freedom in 2021.

A good record across the board, Finland is internationally recognised as a country that upholds democracy well.

Index exists on the principle that censorship can and will exist anywhere there are voices to be heard, but it wouldn’t be too crass of us to say that the world would be slightly easier to peer through our fingers at if its record on key rights and civil liberties were a little more like Finland’s.

It is joint top with Norway and Sweden of non-profit Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index of 2021, third in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2020, sixth in The Economist’s Democracy Index 2020 and second in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index.

Add that together and you have a country with good free speech protections.

That is not to say, though, that when cases of free speech violations do arise, they can be very serious indeed.

In 2019, the Committee to Project Journalists (CPJ) called for Finnish authorities to drop charges against journalist Johanna Vehkoo.

Vehkoo described Oulou City Councilor Junes Lokka as a “Nazi clown” in a private Facebook group.

A statement by the CPJ said: “Junes Lokka should stop trying to intimidate Johanna Vehkoo, and Finnish authorities should drop these charges rather than enable a politician’s campaign of harassment against a journalist.”

“Finland should scrap its criminal defamation laws; they have no place in a democracy.”

Indeed, Finnish defamation laws are considered too harsh, as a study by Ville Manninen on the subject of media pluralism in Europe, found.

“Risks stem from the persistent criminalization of defamation and the potential of relatively harsh punishment. According to law, (aggravated) defamation is punishable by up to two years imprisonment, which is considered an excessive deterrent. Severe punishments, however, are used extremely rare, and aggravated defamation is usually punished by fines or parole.”

The study also spoke of another problem, that of increased harassment or threats towards journalists.

Reporter Laura Halminen had her home searched without a warrant after co-authoring an article concerning confidential intelligence.

Group F[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Strategic lawsuits against public participation (Slapps) are a form of legal harassment used to intimidate and ultimately silence those that speak out in the public interest. Index on Censorship’s research and analysis focuses specifically on Slapps against journalists, but activists, academics, and civil society organisations are also among those affected.

Slapps take many forms, but the most common is civil defamation. According to George Pring and Penelope Canan, American academics who coined the term Slapp in the 1990s, “accusations are just the window dressing”. This is because Slapps tend to lack legal merit and usually end up being dismissed once the facts of the case have been presented in court. This would be good news – but a judge’s decision is not the issue. The amount of time, energy, and money involved in even getting before a judge is vast and can be prohibitive, especially in cases where an individual (as opposed to an organisation) has to foot the bill for their own legal defence.

This means that just the threat of a Slapp can be intimidating enough for a journalist to feel that they should discontinue their research or reporting, or to remove their report from circulation if it has already been published. This is true even though the information is in the public interest and the journalist can prove that it is accurate.

In order to make the Slapp as intimidating as possible, journalists may be told they could be liable to pay vast amounts of money if they publish their story or if they refuse to remove the story if it has already been published. Financial gain, however, is never the aim of a Slapp. Most Slapp plaintiffs (the individuals who start the lawsuit) tend to be wealthy or powerful businesspeople or political figures. Disparity of power and resources is a hallmark of a Slapp.

Journalists facing Slapps are also more likely to be sued individually, even if they are employed with news organisations. This is done in an attempt to isolate them and deprive them of being automatically entitled to the support of their organisations.

In order to make the process as punishing as possible, plaintiffs may try to drag out the legal action. This is done in order to drain journalists of as much time, money, and energy as possible in the hope that they will give up on their reporting. Plaintiffs may also try to file multiple lawsuits in an attempt to ‘bury’ the journalist in litigation. In early 2017, one businessman filed nineteen defamation lawsuits against Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia all at once.

In some cases, plaintiffs may seek to bring cases in jurisdictions that are seen as more plaintiff-friendly. The UK is widely seen as one such jurisdiction. According to research conducted by the Foreign Policy Centre, most of the legal letters received by Europe-based journalists were sent by law firms in the journalists’ own countries (80%), but 31% had been sent by law firms in the UK.

How common are Slapps? The same survey found that 73% of investigative journalists in Europe had received legal communication as a result of information they had published. Most of these (71%) had come from corporations or other business entities. Research carried out by Index on Censorship suggests that they are becoming increasingly common.

Yet, because Slapps are usually communicated to journalists through legal letters marked ‘private and confidential’, they are rarely brought to light. This report is an attempt to bring the practice into the open. Six journalists from Finland, Estonia, Italy and Cyprus recount their experience of facing lawsuits after having published public interest investigations. (Note that these case studies bear the hallmarks of Slapp cases but we make no comment on the bona fides or legal merits of the cases themselves.)

Estonian journalists Mihkel Kärmas and Anna Pihl work on Pealtnägija (Eyewitness), an investigative programme on the Estonian national broadcaster, ERR. “We’re like the Estonian 60 minutes, meaning that we do investigative stories but human interest stories also. We’re on every Wednesday for 45 minutes,” explained Kärmas.

In 2018, after having been contacted by two journalists in Finland, Kärmas and Pihl began working on a new investigation. One part of their investigation focused on the alleged criminal activities of individuals linked to a Finnish non-profit agency in Estonia, particularly the transfer of hundreds of thousands of euro from an Estonian shell company. These individuals are the subject of an ongoing criminal investigation in Finland. The case was also briefly investigated in Estonia before the materials were turned over the Finnish authorities. Another part of their investigation centred on the sale of a Tallinn property that had been owned by the Estonian Centre Party. One of the businessmen linked to the Youth Foundation was involved in the sale.

On 7 November 2018, ERR’s investigation was published in online articles and aired on Pealtnägija.

On 21 December 2018, the Friday before Christmas, the businessman who was allegedly linked to both the Estonian shell company and the sale of the Tallinn property filed a lawsuit against Kärmas, Pihl, and ERR claiming that the investigation had caused ‘injurious action’ and ‘spread false information’.

“We got very extensive court material where they had written up some 18 counts […] whereby we caused significant economic loss,” Kärmas told Index. “They write in their paper that the loss is up to 1 billion euros”.

“A lot of the material that we ended up publishing had already been published in Finland. It’s public knowledge in Finland, and actually a lot of it had been published in print here in Estonia,” Kärmas said. “But regardless of that, we ended up being sued.”

The lawsuit didn’t only name ERR as the defendant, it also named Kärmas and Pihl specifically. It was the first time that any of ERR’s employees were individually sued as a result of their reporting. “At the beginning I was kind of stressed – I was upset I would say,” Pihl said. “First of all I don’t have that kind of money, second of all it would mean that we can’t work as investigative journalists anymore.”

On 7 January 2019, Harju County Court ordered ERR to remove the investigation from its platforms. “It has been taken down and nobody can read it or watch it – both the written and video version. I think it’s concerning because it would be in the public interest that the story is up,” Pihl explained. “This businessman is under criminal investigation – it’s connected with a political party that’s in power, meaning that obviously the public should be able to Google it and go back to it. And also other journalists – if they write new stories – there is useful information for them.”

“Fortunately our TV station was very helpful – they said that they will protect us and that we don’t need to be personally responsible, whatever happens,” said Pihl. “I think that’s the main thing that helped me to be kind of alright with this case is that the public broadcaster said that they are going to pay our court fees and whatever other costs are connected with this case.”

What if she didn’t have that support? “I think I would be very, very stressed because then I would actually think that we might just lose because I wouldn’t have the money to hire a proper lawyer or I would have to use all my savings. That shouldn’t be the case for a journalist because then I would be afraid to publish new stories against businessmen – or anybody basically.”

“In a way, we’re in a lucky position that our media organisation, by Estonian standards, is quite a large one, actually the largest one in Estonia, at least by some standards. We feel quite secure in that respect,” Kärmas said.

“But if you’re a freelancer or working for a smaller media organisation then it’s definitely a headache for instance just to cover the running legal costs. But if this becomes a norm that different parties start bringing legal cases against journalists in Estonia, then we definitely need to think about some sort of security for the journalists involved,” Kärmas said. “I can easily see that this [legal strategy] will make journalists wonder what type of stories they want to take up.”

Despite nearly two years having passed since the lawsuit was filed, little progress has been made. According to Kärmas and Pihl, one of the delays was due to a motion that was filed to the court in September 2019 requesting that a video file of the broadcast be submitted. “They obviously had the video to prepare this lawsuit,” Kärmas said. “Although they had it, we were fully prepared to give it to them. There’s no obstruction from our part, but for some reason we haggled over this for months and months”.

According to Kärmas and Pihl, efforts were also made to prevent their employer from covering their legal fees. “This resulted in a short, separate litigation,” they said, during which ERR was forced to provide details of the contract Pihl and Kärmas had with their defence lawyers. “We were wondering what [they] would do with this information and in the end of July 2020 they sent a letter to the Parliament’s Culture Commission, the Finance Ministry, the Estonian Broadcasting’s governing body, and the State Audit Office asking whether they regard it appropriate use of public funds if the public broadcaster pays for our individual attorneys,” they said.

“From a personal, emotional point of view, it’s very annoying and very difficult. Each step in this litigation takes like three months,” Kärmas said. “So you refresh your memory about all the details, then you answer something, two or three months nothing happens, then there’s another turn, another letter and you have to read up on this again.”

“I realise that it’s going to take… I don’t know how many more years and we haven’t even had any hearings in the court,” Pihl said. “If the other party is angry enough, funded well enough, then they can really make your life difficult,” Kärmas said.

While the litigation continues, their investigation remains unavailable to viewers and readers. “The story is down from online meaning that every day they manage to postpone the case they win a day without the story being up. Even if in the end there would be a decision that we can put it up again. It means they would still win, because for such a long time it wasn’t available,” Pihl explained. The lawsuit is ongoing, pending a final decision from the court.

Freelance journalist Jarno Liski and his colleague Jyri Hänninen, who works for the Finnish national broadcaster YLE, began reporting on the Youth Foundation in mid-2016. “[The story] is highly significant,” Hänninen replied when asked about the case. “It’s one of the biggest financial crimes investigations in Finland.”

It was their reporting that prompted Finnish authorities to start investigating the financial affairs of senior members of the Youth Foundation in 2018. “There’s almost 20 people who are suspected of crimes and the financial harm that these guys have caused is at least 100 million euro,” Hänninen explained.

Liski and Hänninen contacted Pihl and Kärmas, after it came to light that an Estonian shell company had been used in the money transfers. “And we’ve been exchanging information every now and then and trying to help each other out,” Liski said.

Both Liski and Hänninen were shocked when they heard that the reports by their Estonian colleagues had to be removed as a result of a lawsuit. “I was shocked and I was highly surprised that it’s even legally possible in Estonia,” Hänninen said. “I don’t know how the legal system works in Estonia but I was really surprised when I heard about the court decision to censor [the story],” Liski said.

But neither was surprised that a lawsuit had been filed. The same businessman who is suing Pihl and Kärmas filed in Finland a criminal complaint for defamation against Hänninen and Liski in late 2018 for their reporting. In January 2019, the police and the district prosecutor issued its decision not to bring charges against the journalists. “I never had to be officially interviewed or anything,” Liski said.

Another businessman linked to the same investigations repeatedly tried to threaten Liski with legal action. “There was this one businessman who three or four times over two or three years contacted my editors or other superiors and made threats usually about civil lawsuits, where he would demand really big compensation – one million euro. But he never went through with those threats”.

“He was threatening that he would sue me, not the company, but me as a freelance journalist for one million euro for these stories that I’ve written,” Liski explained. “We basically laughed but the threat is real theoretically…”

“His lawyer sent a cease and desist letter to me but that never went anywhere. I think I answered something like ‘the stories are correct and if they are not then I will of course correct them if you tell me what I got wrong’ but that was left there. It’s been like two or three years since I last heard from them,” Liski said. “I’ve hoped and so far I’ve been right, that they don’t want to sue me because they don’t want the publicity. But in Estonia they did what they did and it’s still a mystery to me.”

As a freelance journalist, Liski feels that investigating and reporting on the affairs of wealthy and powerful people puts him in an especially precarious position. Despite reporting on the Youth Foundation story alongside Liski, Hänninen was not subject to the same level of intimidation. Why?

“It’s easier to target a freelance journalist than it is someone who is working – as in my case – for the Finnish national broadcasting company, which is really big with 3,000 employees, and lawyers, and all the other people who can help me out,” said Hänninen.

Liski believes that the news organisations that contract him would support him if he were sued as a freelancer. “But that wouldn’t really solve the problem,” he said. “Because the case would still require me to do so much work: to tell the lawyer what the case is about and write all sorts of answers and go to my archives and find all the documents – the evidence for the stories. And even if all the legal costs were covered, no one would still pay for the hours [it takes] to do that.”

“That would pretty much destroy my career in journalism if for one year I couldn’t write anything that someone could pay me [for],” Liski said.

In 2017, Cypriot journalist Stelios Orphanides was contacted by a whistle-blower about a Libyan-owned company in Limassol, Cyprus. “[They were] offering me information but it was a little bit too convoluted to write a daily report at the Cyprus Mail, where I used to work at the time,” Orphanides explained.

Orphanides started to receive documents from the whistle-blower and began working on an investigation with Sara Farolfi, an Italian investigative journalist who was a freelancer at the time. “It was an amazing amount of documentation that we had to go through, analyse, and make sense of,” Farolfi said.

“In March 2018 we got the go-ahead from the OCCRP [Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project] to investigate and so we started looking into it with the help of this whistle-blower and an American investigator/journalist who was familiar with Libya and who was offering us guidance to make sense of the thousands of pages of material we were forwarded,” Orphanides said. “This is how we came to investigate the story and report it. It took us about six months to work on this story”.

“[O]f course, what we focused on was a piece of the story. We decided to look into Cyprus because that’s where most of the stuff was coming from,” Farolfi said.

On 25 July 2018, Orphanides and Farolfi’s investigation – “Cyprus Records Sheds Light on Libya’s Hidden Millions” – was published on OCCRP’s website.

In August 2018, a lawsuit was filed against Orphanides and Farolfi by a lawyer peripherally connected to the story. That lawyer is named as a plaintiff, alongside four other individual lawyers from his law firm. The lawsuit alleges that Orphanides and Farolfi’s investigation defamed the lawyers, interfered with their professional gravitas and reputation, and exposed them to humiliation and contempt. It also alleges that Orphanides and Farolfi violated their human rights to a private and family life. The lawsuit demands compensation “either together and/or separately” from the journalists.

“It came as a shock,” Farolfi said. “From one side I was certain that we had made no mistake. But when you receive a piece of paper that says ‘you may be asked to pay 2 million euro’, then even if you feel strongly about what you’ve done, it’s scary. I felt shocked to be honest.”

Orphanides said he was less surprised when the lawsuit arrived, but was surprised at the way that it was served to him. “[U]sually when you get sued the court clerks simply give you a call and they say ‘we have this lawsuit and we would like to serve it to you’,” Orphanides explained. “But they didn’t call, or go to the office, instead [the court clerk] came to my place.”

Farolfi said that she didn’t received any notice that she was being sued. “I never received anything. They say they sent me an email, which I never received, and this is quite weird because as an investigative journalist I’m used to checking my spam inbox as well as the normal inbox. And also they had my email address because the publication was a lengthy process and, like always, we sent a request for comment. We sent this request from my email address and from Stelios’ one,” she explained.

According to Farolfi and Orphanides the would-be plaintiff had responded to their request for comment before the investigation was published. “And we included – if not the entire response – a very large portion, and the most significant parts of his response. We haven’t omitted anything of interest to the reader,” Orphanides said.

“Anyway, we were sent the lawsuit and it was personal despite the fact that we had published the investigation with OCCRP,” Farolfi said.

“It’s possible that another purpose of the lawsuit was to know who the whistle-blower that leaked this vast amount of material to us was. This is another aspect of the problem because we, as journalists, will need to protect the identity of this whistle-blower – not to make it public,” Farolfi said.

Orphanides also raised concerns around the plaintiff’s decision to buy the Cyprus Mail in early 2019. The whistle-blower first contacted Orphanides while he was working for the Cyprus Mail and many of the materials used in the investigation were sent to his Cyprus Mail address.

“I was scared mainly because I was freelance,” Farolfi said. “We were very lucky because OCCRP immediately stood by us.” Both she and Orphanides have since been hired by the organisation. “We were immediately reassured even before being hired by OCCRP. [It] is one of the few organisations, as far as I know, that stands by freelance journalists with a lawsuit like this.”

“You feel pretty alone when you get sued, because you are actually alone. I mean I was with Stelios and we had an organisation behind our shoulders, but still you feel a little bit alone. And even more so as freelancers at the time, I think. Especially me – Stelios was not freelance but maybe he felt alone too I don’t know,” Farolfi said.

“There are not many people that understand why you – as a journalist – are undertaking that risk. I remember even chats with friends, slightly looking at me like ‘are you serious you got sued for [up to] two million euro and you are still willing to do this job?’,” Farolfi said. “I remember perfectly that I couldn’t sleep that night and I was thinking ‘Well, that’s a good point. To what extent am I willing to take risks?’.

For Orphanides, the lawsuit was the last straw. “When I got sued for that [OCCRP story] then I realised that I was asphyxiated. It’s not unrelated that a couple of months later, together with my wife, we left Cyprus,” said Orphanides, who now lives in Sarajevo.

Did either of them consider quitting investigative journalism? “I mean the opposite, it convinced me that I had to double down my efforts,” Orphanides said. “I concluded that more investigations were needed and at the same time, doing some investigations in Cyprus was too risky because you would get sued all the time.”

But Orphanides said he feels that his decision to fully focus on investigative journalism means that he will never be able to return to work as a journalist at a Cypriot media outlet. “We have entered a one-way street professionally,” he said. “From the moment that you have done some investigative reporting, you are excluded from the mainstream media market [in Cyprus].”

Like Orphanides, Farolfi also said she never seriously considered changing career. “But I told myself, this is not a job that can be done as a freelancer: ‘this is teaching you that you need to move to a different set-up because this is what I’m going to have to face for any other investigation that I will work on’.”

“There is such a disproportion of forces that unless you have someone behind you – an organisation – and even for an organisation it’s a tough gig,” Farolfi said. “For them to file a lawsuit against two journalists, it just costs nothing. It just costs nothing. They are no downsides. They just need to do what they do every day. They don’t need to allocate any special resources to it. So there is this asymmetry – disproportion of forces.”

Both Farolfi and Orphanides expressed concern over the amount of time they expected the lawsuit to take. “I don’t expect this case will come to the courts before 2025 or so. Maybe longer,” Orphanides said. “Will it be easy for me to remember all the facts in five years?”

“We are lucky to have an organisation behind us. But it’s definitely time-consuming, resource-consuming and stressful,” Farolfi said. “You have this uncertainty like a sword of Damocles over your head,” Orphanides said.

We asked the journalists what advice they would give to fellow journalists who might be facing similar legal threats and actions. They had two main pieces of advice:

“The first piece of advice – a rule if you do investigative journalism – when you publish something it has to be bulletproof,” Sara Farolfi said. “You should make every effort to get all the proof that you need to make your piece more solid. You would be surprised if you knew how long it takes us to get a story published. And it’s all worth it. Totally all worth the time.”

At the same time, she acknowledged that a lot of courage is needed to publish an investigation that involves wealthy or powerful people and to stand by your story once it has been published. “You need to have a thick skin to do this job, certainly,” she said.

“There’s always a risk when you go after these kind of people who have money and influence. It will, of course, take some courage,” Jarno Liski said. “It’s unwise what we do personally when you think about your own situation – there’s not much to win and you could end up in trouble. But it’s important and I encourage people to have more courage.”

“Try to cover your back anyway. As a freelancer, especially, I should have agreed in writing with the media outlets that I write for that they will have my back if we go to court or something like that,” he said. Pihl also advised journalists to speak to their media companies about whether they will support them if they personally face a lawsuit. “I think every journalist has to ask their company if this kind of case happens, if they are going to pay for them,” she said.

“When you’re doing these kinds of investigations on financial crimes and corruption, usually they’re people with a lot of money and a lot of power and they’re using that money and power to intimidate you,” Jyri Hänninen said. “Never stop what you’re doing. It’s always important to bring these out for the general public.”

“At the beginning it’s scary but a court case doesn’t mean that it leads to something,” said Anna Pihl. “Raising this issue is a very good starting point. If we talk more about this – if we raise our concerns about these kinds of cases to a wider audience then hopefully this trend will stop or at least it won’t increase even more.”

“If a journalist has done a crappy job and they are sued because of that then obviously the story should be corrected. But everyone who is working to a high standard shouldn’t be afraid,” she said. “You don’t have to be worried that you can’t write your stories if you’ve done everything correctly. If your work is of a high standard, in the end the journalist will win.”

Pihl also stressed the need for journalists to work together and to have a support network. “This kind of network is very important because if journalists come together they are stronger,” she said. “I don’t have to think ‘maybe if something happens I’m alone’.”

Stelios Orphanides also urged journalists to speak out. “Reporters should perhaps join these efforts that you are making as an organisation and demand that every country – in Europe at least where the rule of law is supposed to be applied – to press for changes to the legislation that would make it more difficult for such lawsuits to be filed against journalists,” he said.

“We need legislation to help us,” Liski said, “legislation and the way it is used is really important. We also have to be careful that we have protections for journalists so that they can write things about powerful people”.

Any effort to silence a journalist poses a threat to the public’s right to information, to rule of law, and ultimately to our democracies. Whether or not an accurate and newsworthy investigation is published shouldn’t depend on a journalist’s courage or their determination to serve the public interest above their own. Concrete action is urgently needed to support journalists and protect them from falling victim to legal harassment.

Anti-Slapp statutes exist in several states, including in Canada and the United States. Similar anti-Slapp legislation, in the form of an EU directive, would offer the most comprehensive protection not only to journalists but to activists, academics, and civil society organisations. Such a directive should provide for Slapps to be dismissed at an early stage of proceedings, for Slapp litigants to face financial penalties for abusing the law, and for Slapp victims to be given the means and support to defend themselves.

Special thanks to Anna Pihl, Mihkel Kärmas, Jarno Liski, Jyri Hänninen, Sara Farolfi, and Stelios Orphanides. Photo credits: Anh Nguyen/Unsplash (main image), PDPics/Pixabay (newspapers)[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”113711″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://postkodstiftelsen.se/en/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]This report has been supported by the Swedish Postcode Foundation. The foundation is a beneficiary to the Swedish Postcode Lottery and provides support to projects that foster positive social impact or search for long-term solutions to global challenges. Since 2007, the foundation has distributed over 1.5 billion SEK in support of more than 600 projects in Sweden and internationally.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_hoverbox image=”115716″ primary_title=”Are you facing a Slapp? Find out here” hover_title=”Are you facing a Slapp? Find out here” hover_background_color=”black” hover_btn_title=”Use our tool” hover_btn_color=”danger” hover_add_button=”true” hover_btn_link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fam-i-facing-a-slapps-lawsuit%2F” el_class=”text_white”][/vc_hoverbox][vc_empty_space][vc_hoverbox image=”115715″ primary_title=”Read our report, Breaking the Silence” hover_title=”REPORT: Breaking the Silence” hover_background_color=”black” hover_btn_title=”Read the report” hover_btn_color=”danger” hover_add_button=”true” hover_btn_link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fcampaigns%2Fbreaking_the_silence_report_slapps%2F” el_class=”text_white”][/vc_hoverbox][vc_empty_space][vc_hoverbox image=”115717″ primary_title=”Read our report, A gathering storm” hover_title=”REPORT: A gathering storm” hover_background_color=”black” hover_btn_title=”Read the report” hover_btn_color=”danger” hover_add_button=”true” hover_btn_link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fcampaigns%2Fthe-laws-being-used-to-silence-media%2F” el_class=”text_white”][/vc_hoverbox][vc_empty_space][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”smartslider_area_1″][vc_empty_space][vc_hoverbox image=”115716″ primary_title=”Are you facing a Slapp? Find out here” hover_title=”Are you facing a Slapp? Find out here” hover_background_color=”black” hover_btn_title=”Use our tool” hover_btn_color=”danger” hover_add_button=”true” hover_btn_link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fam-i-facing-a-slapps-lawsuit%2F” el_class=”text_white”][/vc_hoverbox][vc_empty_space][vc_hoverbox image=”115715″ primary_title=”Read our report, Breaking the Silence” hover_title=”REPORT: Breaking the Silence” hover_background_color=”black” hover_btn_title=”Read the report” hover_btn_color=”danger” hover_add_button=”true” hover_btn_link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fcampaigns%2Fbreaking_the_silence_report_slapps%2F” el_class=”text_white”][/vc_hoverbox][vc_empty_space][vc_hoverbox image=”115717″ primary_title=”Read our report, A gathering storm” hover_title=”REPORT: A gathering storm” hover_background_color=”black” hover_btn_title=”Read the report” hover_btn_color=”danger” hover_add_button=”true” hover_btn_link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fcampaigns%2Fthe-laws-being-used-to-silence-media%2F” el_class=”text_white”][/vc_hoverbox][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

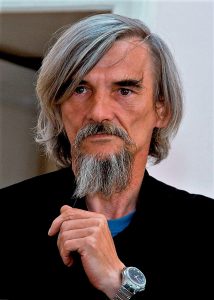

Russian historian Yuri Dmitriev, who has been imprisoned following research into murders committed by Stalin. Credit: Mediafond/Wikimedia

Western democracies have expressed concern and outrage, at least verbally, over the Novichok poisoning of Alexei Navalny—and this is clearly right and necessary. But much less attention is being paid to the case of Yuri Dmitriev, a tenacious researcher and activist who campaigned to create a memorial to the victims of Stalinist terror in Karelia, a province in Russia’s far northwest, bordering Finland. He has just been condemned on appeal by the Supreme Court of Karelia to thirteen years in a prison camp with a harsh regime.

The hearing was held in camera, with neither him nor his lawyer present. For this man of sixty-four, this is practically equivalent to a death sentence, the judicially sanctioned equivalent of a drop of nerve agent.

After an initial charge of child pornography was dismissed, Yuri Dmitriev was convicted of sexually assaulting his adoptive daughter. These defamatory charges appear to be the latest fabrication of a legal system in thrall to the FSB—a contemporary equivalent, here, of the nonsensical slander of “Hitlerian Trotskyism” that drove the Great Terror trials. It is these same charges, probably freighted with a notion of Western moral decadence in the twisted imagination of Russian police officers, that were brought in 2015 against the former director of the Alliance Française in Irkutsk, Yoann Barbereau.

I met Yuri Dmitriev twice: the first time in May 2012, when I was planning the shooting of a documentary on the library of the Solovki Islands labor camp, the first gulag of the Soviet system; and the second in December 2013, when I was researching my book Le Météorologue (Stalin’s Meteorologist, 2017), on the life, deportation, and death of one of the innumerable victims murdered by Stalin’s secret police organizations, OGPU and NKVD.

In both cases, Dmitriev’s help was invaluable to me. He was not a typical historian. At the time of our first meeting, he was living amid rusting gantries, bent pipes, and machine carcasses, in a shack in the middle of a disused industrial zone on the outskirts of Petrozavodsk—sadly, a very Russian landscape. Emaciated and bearded, with a gray ponytail, he appeared a cross between a Holy Fool and a veteran pirate—again, very Russian. He told me how he had found his vocation as a researcher—a word that can be understood in several senses: in archives, but also on the ground, in the cemetery-forests of Karelia.

In 1989, he told me, a mechanical digger had unearthed some bones by chance. Since no one, no authority, was prepared to take on the task of burying with dignity those remains, which he recognized as being of the victims of what is known there as “the repression” (repressia), he undertook to do so himself. Dmitriev’s father had then revealed to him that his own father, Yuri’s grandfather, had been shot in 1938.

“Then,” Dmitriev told me, “I wanted to find out about the fate of those people.” After several years’ digging in the FSB archive, he published The Karelian Lists of Remembrance in 2002, which, at the time, contained notes on 15,000 victims of the Terror.

“I was not allowed to photocopy. I brought a dictaphone to record the names and then I wrote them out at home,” he said. “For four or five years, I went to bed with one word in my head: rastrelian—shot. Then, I and two fellow researchers from the Memorial association, Irina Flighe and Veniamin Ioffe (and my dog Witch), discovered the Sandarmokh mass burial ground: hundreds of graves in the forest near Medvejegorsk, more than 7,000 so-called enemies of the people killed there with a bullet through the base of the skull at the end of the 1930s.”

Among them, in fact, was my meteorologist. On a rock at the entrance to this woodland burial ground is this simple Cyrillic inscription: ЛЮДИ, НЕ УБИВАЙТЕ ДРУГ ДРУГА (People, do not kill one another). No call for revenge, or for putting history on trial; only an appeal to a higher law.

Memorials to the victims of Stalin’s Terror at Krasny Bor, Karelia, 2018; the remains of more than a thousand people shot between 1937 and 1938 at this NKVD killing field were identified by Dmitriev, using KGB archival records

Not content to persecute and dishonor the man who discovered Sandarmokh, the Russian authorities are now trying to repeat the same lie the Soviet authorities told about Katyn, the forest in Poland where NKVD troops executed some 22,000 Poles, virtually the country’s entire officer corps and intelligentsia—an atrocity that for decades they blamed on the Nazis. Stalin’s heirs today claim that the dead lying there in Karelia were not victims of the Terror but Soviet prisoners of war executed during the Finnish occupation of the region at the beginning of World War II. Historical revisionism, under Putin, knows no bounds.

I am neither a historian nor a specialist on Russia; what I write comes from the conviction that this country, for which I have a fondness, in spite of all, can only be free if it confronts its past—and to do this, it needs courageous mavericks like Yuri Dmitriev. And I write from the more personal conviction that he is a brave and upright man, one whom Western governments should be proud to support.

This article was translated from the French by Ros Schwartz. It was originally published on the New York Review of the Books here under the headline Yuri Dmitriev: Historian of Stalin’s Gulag, Victim of Putin’s Repression.

Read our article exploring Dmitriev’s case and how history is being manipulated and erased here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]