Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

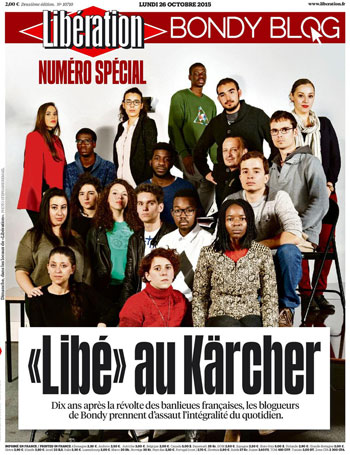

The cover of a special issue of Libération done in collaboration with the Bondy Blog, 10 years after the October 2005 riots.

This January, the trial of a police officer who had been accused of the 2012 shooting a man in the back took place near Paris. The victim was called Amine Bentounsi and was of North African origin. At the end of the proceedings, the police officer was cleared.

Journalists wrote that, with Bentounsi’s relatives present, as well as members of the police who had come to support their colleague, the atmosphere was tense. They also reported that a freelance journalist of Northern African origin called Nadir Dendoune suffered from discrimination in court, when he was the only one to be asked for his press card by a police officer while sitting among fellow journalists.

“It was 9:35am and I was sitting among other journalists when some police officers approached me, asking to see my press card. I said I’d show it to them if they asked the others as well. But the defense attorney requested silence so I decided not to make a fuss and showed my card. At noon, one of my female colleagues went to ask the officer why he had asked for my card and he said it was because he didn’t know me, except I probably come more often than her,” Dendoune told Index on Censorship.

Dendoune has worked as a journalist in print and TV for 10 years. He says he is constantly asked for his press card while on the job.

“In 2008 or 2009, I was covering something that had happened in Bondy. There must have been around 40 journalists. A police officer came to see me and told me that only journalists were allowed to be there. In France, some seem to think that you can’t be an Arab and a journalist.” That this would be the case is not suprising in a country where arbitrary and discriminatory stop and searches are usual, he said. During the presidential campaign, François Hollande promised police officers would hand receipts after a stop and search, but this promise, which was seen as an important step to improve relationships between the police and the ethnically diverse inhabitants of France, was soon dropped.

France doesn’t collect ethnic statistics, which means there is no data on the representation of minorities in society.

“[The lack of ethnic stats] seems to make it harder to put words on this”, journalist Widad Kefti told Index. She learned the ropes of journalism at the Bondy blog, a site which was created after the death of teenagers Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré in Clichy-sous-bois sparked riots in France’s suburbs in 2005. The Bondy blog has been instrumental as an incubator of new voices.

Last October, 10 years after Benna and Traoré’s deaths, Libération published an anniversary issue in collaboration with the Bondy blog, which included Kefti’s “Open letter to newsroom directors” calling on them to hire more journalists with diverse backgrounds. “I decided the tone of the article needed to be angry, angry like my generation, who are sick of being told that change takes time. People who are older than us had a softer approach, but it hasn’t worked.”

She said her piece prompted two types of reactions: “Some told me that I was speaking nonsense and that the only thing that mattered was social diversity. But some TV and print editors contacted me to say the letter had helped them realise there was a problem in their newsroom, wanting to discuss what could be done to change this.”

The classic path to becoming a reporter in France is to enroll in a journalism school, which have selective admission policies. “It’s very complicated to get in, very closed”, Kefti said. “At the Bondy blog, we created a free preparatory course for people with diverse backgrounds, which is based on social criteria, and we’ve had great results.”

She points to Ilyes Ramdani, a young blogger turned journalist from Aubervilliers, now in his early 20’s, who came first at the entrance competition of Lille journalism school and would not have applied had it not been for the Bondy Blog preparatory course.

Even graduating from journalism school is no guarantee, Kefti said. From what she has seen, the sector hires little, which has led to a precarious existence for new journalists, and made the profession less accessible to those who don’t have financial resources to pursue the career.

Kefti plans to create a think thank of French journalists coming from diverse backgrounds that will host a brunch every month to discuss terminology with journalists, as she is convinced the lack of diversity in newsroom has an impact on the way the news is being framed. Having become tired of seeing panels of white men supposedly representing the French TV audience, she also wants to create an academy to provide media training to experts of diverse ethnic backgrounds. Social media, which has democraticised influence, can help make newsrooms more diverse as French newspapers continue their transition to digital journalism, she said.

“To me, you really have to be stupid to fail to realise what a person of a diverse ethnic background can bring to a newsroom”, Kefti said.

This article was originally posted at Index on Censorship

Mapping Media Freedom

|

Editorial Credit: Frederic Legrand – COMEO / Shutterstock.com

Even before the attacks on Paris on 13 November were over, French President Francois Hollande declared a nationwide state of emergency giving authorities additional powers in the name of protecting citizens and combatting terrorism. But since the attacks, concerns have been raised for press freedom prompted by the cancellation of a regular radio segment by journalist Thomas Guénolé.

A few days after the events of 13 November, Guénolé devoted his daily morning commentary piece on RMC radio to what he perceived as the failings of the French security services and police. On the same day, the Interior Ministry called Philippe Antoine, RMC managing editor, to demand the radio station air a corrective to points Guénolé discussed during his segment, which the ministry would pen. “Interestingly, the corrective was not going to appear as a corrective emanating from the Interior Ministry but as the correction of an inaccurate information emanating from RMC,” Guénolé told me.

The proposed corrections were in relation to Guénolé’s discussion of claims reported by various news outlets, including that France had known since August 2015 that IS planned to attack a rock concert in France and that Turkish authorities had warned France twice this year about Omar Ismaïl Mostefaï, one of the assailants of the Bataclan massacre.

Guénolé called for a parliamentary investigation which should, if these claims were true, prompt the resignation of the highest ranking French officials, including Bernard Cazeneuve, France’s Minister of the Interior.

Guénolé also repeated information published by La Lettre A, which claimed only three out of 50 members of the Parisian Brigade de recherche et d’intervention (an anti-gang unit, which is to intervene in hostage situations) had been on duty after 8pm on the night of the attacks. On 19 November, the special adviser to France’s interior minister, Marie-Emmanuelle Assidon, took to Twitter to say the information contained in La Lettre A was false but recognised she had not read the article. “[N]o one but Thomas Guénolé trusts your info,” she added in her tweet.

“I have repeatedly asked Place Beauvau for a denial,” Marion Deye, editor at La Lettre A, told me. “I haven’t had one.” Neither have Le Monde or the AFP, also quoted by Guénolé.

“We published a very factual piece of news on the Monday following the attacks, at a time when any type of criticism was not welcome,” Daye said. “However, what we published was not a criticism, just a report. The most absurd thing in this whole story is that no one knows what Place Beauvau denied when they spoke to RMC. I think what was really problematic for some was that Guénolé brought up the resignation of Cazeneuve.”

On Friday 20 November, Guénolé was informed that his daily column was cancelled. In an email, the RMC managing editor wrote: “The Interior Ministry and all the police services invited on air have refused to appear on RMC because of inaccuracies in your column. Most sources of our police specialists have gone silent since Tuesday, putting in jeopardy the work that our editorial team does to find and verify information.”

Guénolé described the actions against him as both a “boycott” and an “embargo”.

“One would expect a media outlet to back up its journalist and not to have too strong a dependency vis-à-vis institutions,” he said. “My particular case doesn’t matter so much. What is unacceptable is that the Interior Ministry seems to have pressured RMC because they were displeased with what a journalist said on air in the context of the state of emergency.”

The firing of Guénolé happened on the on the same day the Assemblée Nationale voted to extend the state of emergency from 12 days to three months. Measures to control the press were initially proposed by 20 socialist MPs led by Sandrine Mazetier on the basis that the coverage of the January 2015 attacks in Paris – especially by news channel BFM-TV – had endangered the life of hostages who were hiding in a Hyper Casher supermarket. Such a measure would be highly problematic. As Mathieu Magnaudeix, a journalist with the investigative website Mediapart, put it to me: “If we were to end up with an authoritarian power, which by now doesn’t seem to be out of the question, what could they do with a law that allows the control of the press?”

Thankfully, the press control measures were later dismissed and it was made clear that even Hollande was strongly opposed. Regardless, it is apparent journalists still aren’t safe.

The proposed law does, however, extend and harden house arrests that are allowed under a state of emergency, enables members of the police force to carry their weapons while off duty, gives stronger powers to the authorities to carry police searches that are not approved by a judge. While these cannot be carried out in the workplace, police searches can take place at the house of an MP, lawyer, a judge or a journalist.

This kind of anti-terror legislation, as we have seen in the UK, could have further negative consequences for journalists covering terrorism.

|

Mapping Media Freedom

|

Vincent Bolloré is known for business takeovers. Now 63, he has built an empire in energy, agriculture, transport and logistics.

The billionaire is also a media mogul with expanding interests. His investment group Bolloré, named for its president and CEO, has a majority share in Havas, a leading French advertising and PR group. It owns the cable television channel D8 and the daily newspaper Direct Matin.

Bolloré was appointed as president of Vivendi, the French mass media company, in June 2014. Vivendi owns Canal Plus, a French subscription-based television channel known for its irreverent tone, where Bolloré became chairman last September.

A common theme is emerging in Bolloré’s professional life. As he attains more media companies, there are increasing attacks on editorial content he disapproves of. Last June, Le Canard Enchaîné revealed that Havas, a French multinational advertising and public relations company, which is controlled by the Bolloré group, had cut the advertising budget in Le Monde by €3.2 million in 2014 and €4 million in 2015. This followed the publication of two articles that Bolloré disliked — a personal profile and a report on the activities of the Bolloré group in the Ivory Coast.

“It can be hard to understand whether a media owner is doing something to improve the health of his business or whether he is meddling with editorial content,” says Virginie Marquet, a lawyer who specialises in freedom of the press and co-founder of the collective Informer N’est Pas Un Délit (To Inform Is Not A Crime). “What’s new with Bolloré is the brutality of what is taking place.”

Pierre Siankowski is the former culture editor for Le Grand Journal, a primetime talk show which was broadcast on Canal Plus every weekday and produced by independent production company KM. On 3 July, he found himself out of a job when Bolloré personally decided KM would stop producing the talk show. “The reason given is that the show was too expensive and that Bolloré wanted it to be produced internally,” Siankowski says. “But there’s actually an article in Le Parisien that claims the current cost of production is roughly the same.”

For Siankowski, there may be another reason. He says Renaud Le Van Kim, producer of Le Grand Journal, who is believed to have been made to leave the company he created at Bolloré’s demand, and Rodolphe Belmer, former director of Canal Plus who was fired in July, had both expressed support for Les Guignols De L’info — a satirical news bulletin broadcast on Canal Plus where politicians are played by latex puppets — amid rumours the show was under threat.

The puppets are currently in the closet, having been temporarily taken off the air. The show is due to return in November, but on Bolloré’s orders, it will have more of an international focus, and therefore less coverage of French politics. It may also lose its prime-time slot.

Does Siankowski think the attack against Les Guignols might be politically motivated? Is it a gift from Bolloré to Nicolas Sarkozy, who was a frequent target of the show? “Here is what we know: after he got elected, Sarkozy went on holiday on Bolloré’s yacht,” he says. “We also know Sarkozy hated Les Guignols, and that in a few months’ time the political campaign for the presidential election will start.”

Meanwhile at Canal Plus, there were other worrying signs. In July, it was revealed that a documentary on tax evasion at the Crédit Mutuel bank — one of the main financial partners of the Bolloré group — which was scheduled to be broadcast on Canal Plus in May, had been removed from the programme before it was supposed to air. Geoffrey Livolsi, co-director of the documentary, said Belmer had received a phone call from Bolloré, who requested it be axed following a conversation with Michel Lucas, CEO of Crédit Mutuel.

When asked by staff representatives to explain the decision, Bolloré allegedly replied: “You don’t kill your friends.”

The documentary was finally shown on France 3 in October.

In September,another documentary, this time on the rivalry between Sarkozy and French President Francois Hollande, was taken off Canal Plus grid without explanation, before reappearing a month later.

“What this shows is that we don’t have the tools that are needed to protect press freedom,” Marquet says. “This is why we felt we need to mobilise.”

“What we would like to see are sanctions,” Marquet adds, reminding us of the existence of a resolution voted in 2013 by the European Parliament. It states: “Governments have the primary responsibility of guaranteeing and protecting freedom of the press and the media” and considers “the trend of concentrated media ownership in large conglomerates to be a threat to media freedom and pluralism”.

Bolloré’s attack on the media isn’t confined to those organisations in which he has an influence. He has taken legal action against journalists and publications to defend his business interests. His group has sued, among others, rue89, France Inter, Libération and Bastamag. It also took journalist Benoît Collombat to court over an investigation he had done on the group’s activities in Cameroon.

Asked what he thought of “the Canal Plus spirit” on 12 February on France Inter, Bolloré replied: “It’s a spirit of discovery, of openness, sometimes of excessive derision.” On that same evening, Les Guignols featured Bolloré’s puppet, who was asked to define what “acceptable derision” means. It seems the real life billionaire’s answer to that question has been clear.

|

Mapping Media Freedom

|

The decision not to air the last episode of Du Jour au Lendermain and recent budget cuts have critics up in arms over changes to the cultural arm of Radio France.

Alain Veinstein, a French writer and poet has been hosting the radio programme called Du jour au lendemain for 29 years on France Culture, a French public station dedicated to culture.

Olivier Poivre d’Arvor, director of France Culture, decided not to air Veinstein’s last show, dating from 4 July, unhappy that the host had decided to interview himself and not a writer, and to talk about what the end of his show meant to him. A programme dating from November was re-aired instead. Veinstein denounced “a rare case of censorship on the radio” while talking to Le Monde.

In the end, the director of France Culture decided to make the programme available online. In a 35 minute-long monologue, Veinstein explained he had learned by email that same morning that his programme would be discontinued.

“It would have been fine for him to say farewell for 3 minutes, even to express negative views on the fact his programme was discontinued. But my job is to make sure that the radio is not taken hostage. There was something obscene in explaining that after him it would be chaos”, Poivre d’Arvor told Libération.

“A public radio station is not a private one, nor a place to do a pro domo speech, not for Alain Veinstein or any of us. (…) Ensuring the renewal of generations on the radio is to strenghten France Culture’s future”, he continued.

Several personalities who have been working for Radio France for a long time – David Mermet, Ivan Levaï – have been dismissed recently, in a move that seems to show the new management of Radio France wants to appeal to a youth audience by employing younger presenters.

On the listeners forum, there were some very hostile reactions to Poivre d’Arvor’s decision.

“From someone who’s constantly reduced the importance of culture on France Culture radio to reinforce news, tacky sensationalism, while adding a dose of mediocre tourism, it’s a bit much to say this programme didn’t fit in”, wrote one commenter. Another listener added: “Why is Poivre d’Arvor deciding instead of the programme’s producer what is going to be of interest to the audience?”

In February, the Conseil national de l’audiovisuel (CSA), an institution whose role is to regulate the various electronic media in France, such as radio and television, named 37 year-old Mathieu Gallet as the new head of Radio France. Under the Sarkozy presidency, Gallet is known to have helped writing a law that enabled the French president to name the heads of public television. This power has now been returned to the CSA.

At the end of June, the management of France Culture announced a 7.5 per cent cut in the budget for all shows except news broadcasts. In a joint release, the society of producers of France Culture, France Inter and France Musique denounced the fragility of radio hosts, who are not France Culture employees but “intermittents du spectacle”. Veinstein discussed the “intermittent” status in his last programme.

Under French law, some 250,000 workers in the film, theatre, television and festival industry, known as intermittents, benefit from a system that pays them during periods when they do not work. Many of them have been keeping the pressure on during summer festivals, and went out on strke, as they are unhappy with a deal reached between some unions, employers and the government in March which would increase their payroll taxes.

As Veinstein put it in his Le Monde interview: “Night has fallen for good. Don’t ask me what tomorrow will be made of. Tomorrow is today without tomorrow (…) It’s been a beautiful day, all the same. Du jour au lendemain is entering the past.’

Recent reports from France via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com:

Accused of collecting data on journalists, Front National threatens them

This article was posted on July 14, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org