Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

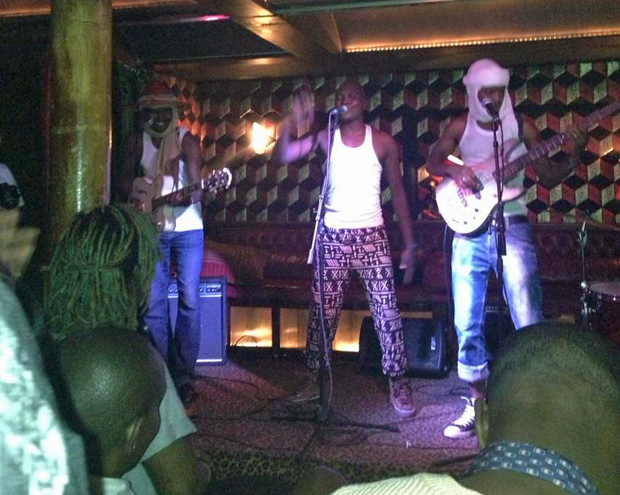

Songhoy Blues, musicians featured in the film

Index on Censorship has teamed up with the producers of the award-winning They Will Have To Kill Us First for the launch of the Music in Exile Fund to support musicians facing censorship globally.

In 2012, Muslim extremist groups captured northern Mali, implemented sharia law and banned all music. Musicians’ instruments were destroyed and even musical ringtones were prohibited. They Will Have To Kill Us First: Malian Music In Exile tells the stories of the Malian musicians who fought back and refused to have their music taken away.

The film’s director, Johanna Schwartz, told Index on Censorship about the bravery of the musicians and the current situation in Mali.

“I’ve always been extremely interested in Africa,” Schwartz said. “When I heard that music had been banned I got on an airplane and went.” She didn’t decide there and then to make the film, but as the story affected her, she had started working on one without realising it. “It’s one of those stories that just shocks your soul.”

It was also the general lack of knowledge about what was going on in Mali that encouraged Schwartz to make the film. “The rise of extremism in Africa is quite confusing. People aren’t really sure why, where or to whom it’s happening,” Schwartz said. “The rise of extremism in Mali and west Africa is something that we all need to know a lot more about, and, in a way, the film doesn’t even begin to cover it.”

Telling the story through the eyes of musicians was a way to humanise some of the headlines that people had been reading about.

Since Schwartz started making the documentary the situation in Mali has seen some promising changes, but the future is still very much uncertain for the country’s musicians. “When I started there were three extremist groups in control of the entire north of the country. Then the French army came in and took the north back on behalf of the Malian government,” she explained. “The French intervention wasn’t entirely successful in eradicating the extremist groups and while they aren’t in control of the north anymore, they’re still staging attacks and musicians are still incredibly fearful. Life is definitely not back to normal.”

Music plays a huge role in Malian society. Disco, a musician featured in the film, discusses how music is a way to teach morality and to get your message across, whether it be about health, beauty, education or politics. Many believe the importance of mucic to everyday life in Mali is why it was attacked so specifically.

Schwartz added that getting to know the musicians while following their journey was the best part of making the documentary. “I am always incredibly appreciative when you go out and meet strangers and they trust you, invite you into their life and share with you everything that they’re experiencing.”

“I’m in awe of the bravery of all of these musicians. It’s been incredible to be with them as they’ve gone through this,” she said. “They all had a great deal to say about what’s happened in Mali and they all represent different aspects of life there since the music ban.”

Schwartz pointed to the success experienced by 2014 Index arts award nominees Songhoy Blues, a four-strong “desert blues” band made up of musicians who fled northern Mali. “When we met Songhoy Blues they were refugees and now they’re literally international superstars”, she said. “Watching them get their manager, watching them record their first album, watching them perform it for the first time, watching them go on tour for the first time, play the Royal Albert Hall, go on and International tour, it’s been incredible to be with them.”

Schwartz wants the film to open people’s eyes. “There’s a lot that can be done with this film in terms of widening people’s perspectives, especially in places like France and the US where there are a lot of anti-Muslim feelings right now. Just like 98% of people in Mali, every single person in this film is Muslim, and a lot of people don’t realise that these extremist groups are attacking people who are already Muslim.”

Despite the serious issues in the film, which will be screened in UK cinemas in October, Schwartz hopes it will have a positive impact on people: “Even though this is a film about conflict, war and censorship, it’s ultimately hugely uplifting and inspirational. People can come out of it feeling quite positive about the impact these musicians are having.”

Songhoy Blues, performing in London, asked the audience to imagine music being banned in the UK.

Aliou Touré, lead vocalist of the Malian band Songhoy Blues, introduced their concert in London by talking about the challenges musicians face in Mali, where music was banned by a local armed Islamist group in the north of the country in 2012.

“It is liberating to be able to perform tonight because in my country, I do not have the same freedom of expression,” Touré added before the kick off.

As the concert rolled on, one could easily forget that Songhoy Blues — who are touring in the UK ahead of their album launch later in the year — were deprived from playing music at home.

In September 2013, documentary filmmaker Johanna Schwartz wrote for Index on Censorship magazine on the censorship and persecution that musicians in Mali have faced since the ban on music: “There is a fear that freedoms may not be so easily restored,” wrote Schwartz. Today, although the ban has been theoretically lifted, the fear remains. “Because of the violence, it is still impossible for me to play music in my hometown,” said Touré, who is from the northern city Gao.

Like thousands of refugees, Touré left for Bamako amid escalating violence.

In the capital city, Touré and other musician friends — Garba, Oumar and Nathanael — from the north decided to form a band. The very creation of their band is an act of hope and resistance: “Somehow, the ban on music played in our favour because it’s only after we left the north that we came together and formed Songhoy Blues,” explained Touré.

The band is now based in Bamako, where the members long for the weekend to perform in local bars. But as music was being driven out of the country — even those with musical ringtones on their mobile phones faced crackdowns — many musicians fled Mali. They Will Have to Kill Us First, Schwartz’s feature-length documentary, follows the story of Mali’s musical superstars as they fight for their right to sing.

At this time, They Will Have to Kill Us First is in the final stages of shooting, and it is still uncertain if Songhoy Blues and the other Malian musicians in exile will feel safe enough to return to home.

This article was posted on July 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Music Freedom Day is a global collaboration to raise awareness of the challenges many musicians face around the world in creating their music. In 2013, 19 musicians were killed, seven abducted and 18 spent time in jail for using their right to free speech to express themselves through music, according to the human rights organisation Freemuse.

Mali is one such country where musicians have faced persecution and censorship for their work.

Documentary filmmaker Johanna Schwartz wrote for Index on Censorship magazine on the censorship and persecution that musicians in Mali have faced from Islamists, with musician Fadiamata Walet Oumar.

In the article they highlighted how music was being driven out of the country, with even those with musical ringtones on their mobile phones facing crackdowns. Many musicians fled Mali during the worst excesses of persecution, as the article charts. Schwartz is an award-winning documentary maker, and she is giving Index readers an exclusive preview of her documentary They Will Have To Kill Us First.

Also in this issue of the magazine:

• Azerbaijan’s photographers: Facing arrest for capturing the raw truth

People in territories controlled by al-Shabab are banned from using “mobile internet and fiber optic technology”, the group announced in a radio message and subsequent written statement on Wednesday. Internet service providers have been given 15 days to comply with the ban.

The country’s two main ISPs, Hortel Inc and Nationlink Telecom, had this morning yet to respond to the demands, reports Al Jazeera English. Details on how such a ban would be effectively implemented and enforced, beyond that those found to be in violation of it would be “considered to be working with the enemy” and “dealt with in accordance Sharia law” were not provided.

While al-Shabab has lost some footing in recent times, especially in urban areas, they still hold control in many rural parts in the country. This is not the first time that control has been used to crack down on access to freedom of expression. Late last year, the group banned use of smart phones and satellite TV. Previously, they have banned BBC radio broadcasts.

This latest moved comes not long after news that Somalia is to get high speed internet from 2014.